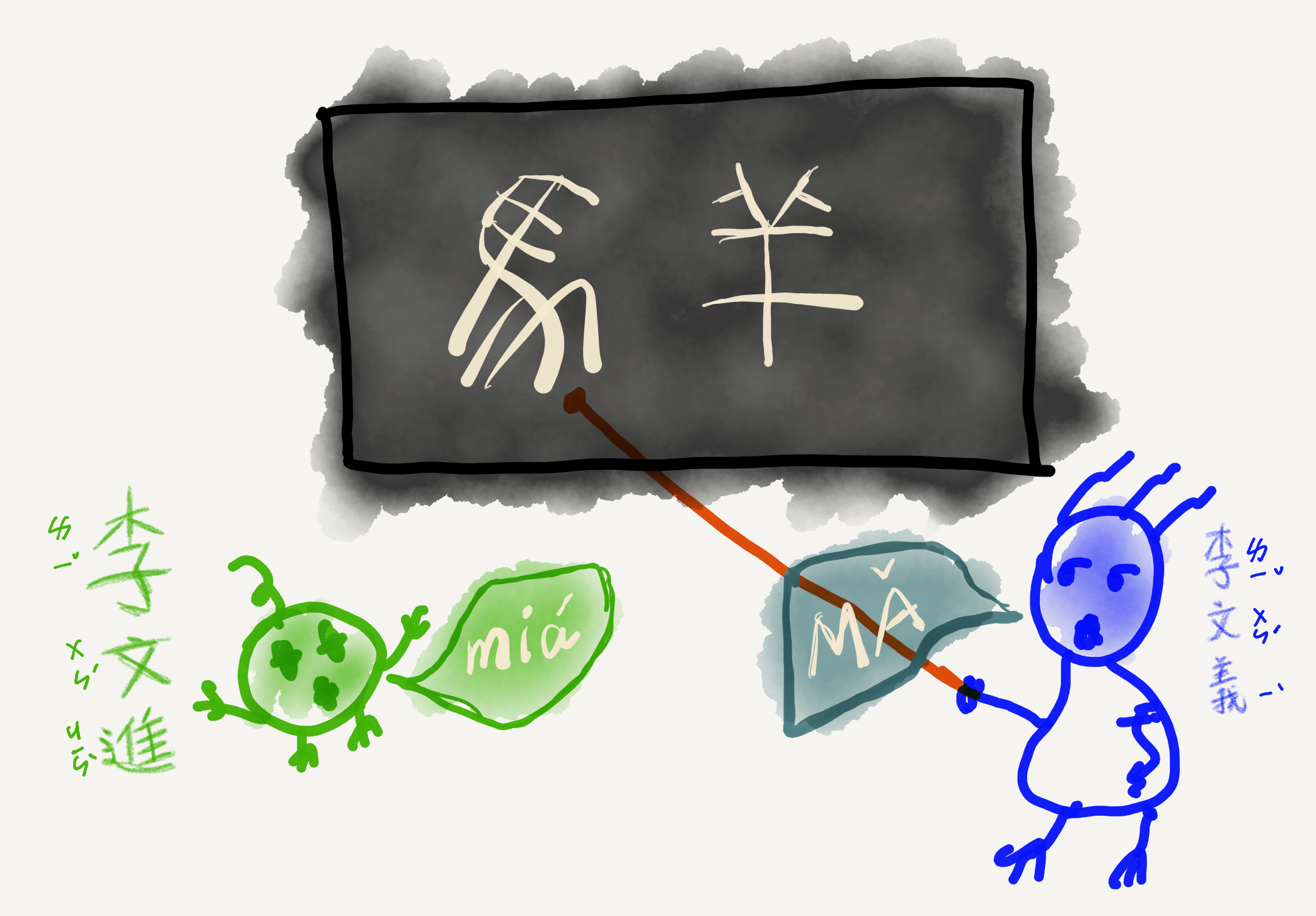

Yesterday I saw a trending hashtag on Weibo (the Chinese Twitter): #一千年前小朋友写的字, which translates as “characters written by kids from 1000 years ago.” I clicked on it out of curiosity and found some amusing doodles on the back of a 9th-century manuscript (see the banner above). The doodles include 13 animals and a descriptive caption for each of them in the format “this is …” (e.g., “this is a horse”), and the manuscript, indexed P.2622 and now in France, was among the historical manuscripts discovered in 1900 in Dunhuang, China.

Background info

The Dunhuang manuscripts are highly valuable in many respects (there’s a whole research field about them), though I don’t know why this particular doodler has suddenly become an Internet celeb in 2021 😂. Netizens were guessing yesterday that doodles like these must have been the work of a kid (hence the above hashtag) but someone with the usersame @科学未來人 later revealed (based on a 2010 paper) that the doodler had actually been a 22-year-old young adult (named Li Wenyi), who had possibly used the doodles to teach his little brother (Li Wenjin) animal names.

The majority of Weibo users merely had a laugh, but I thought the doodles would actually make an excellent teaching material in ancient Chinese class, because apart from the cute animals they also contain something else, including (based on the above-mentioned paper) three lines copied from the famous Lántíngjí Xù, some fragmentary student poems, some debtors’ names, and some random babble (e.g., “this is the manuscript of Li,” “receive your punishment immediately [in a Taoist exorcist’s tone]”). 👀

Here I use “ancient Chinese” as a cover term for the various written/colloquial Chinese varieties used in ancient China (“ancient” in a broad sense).

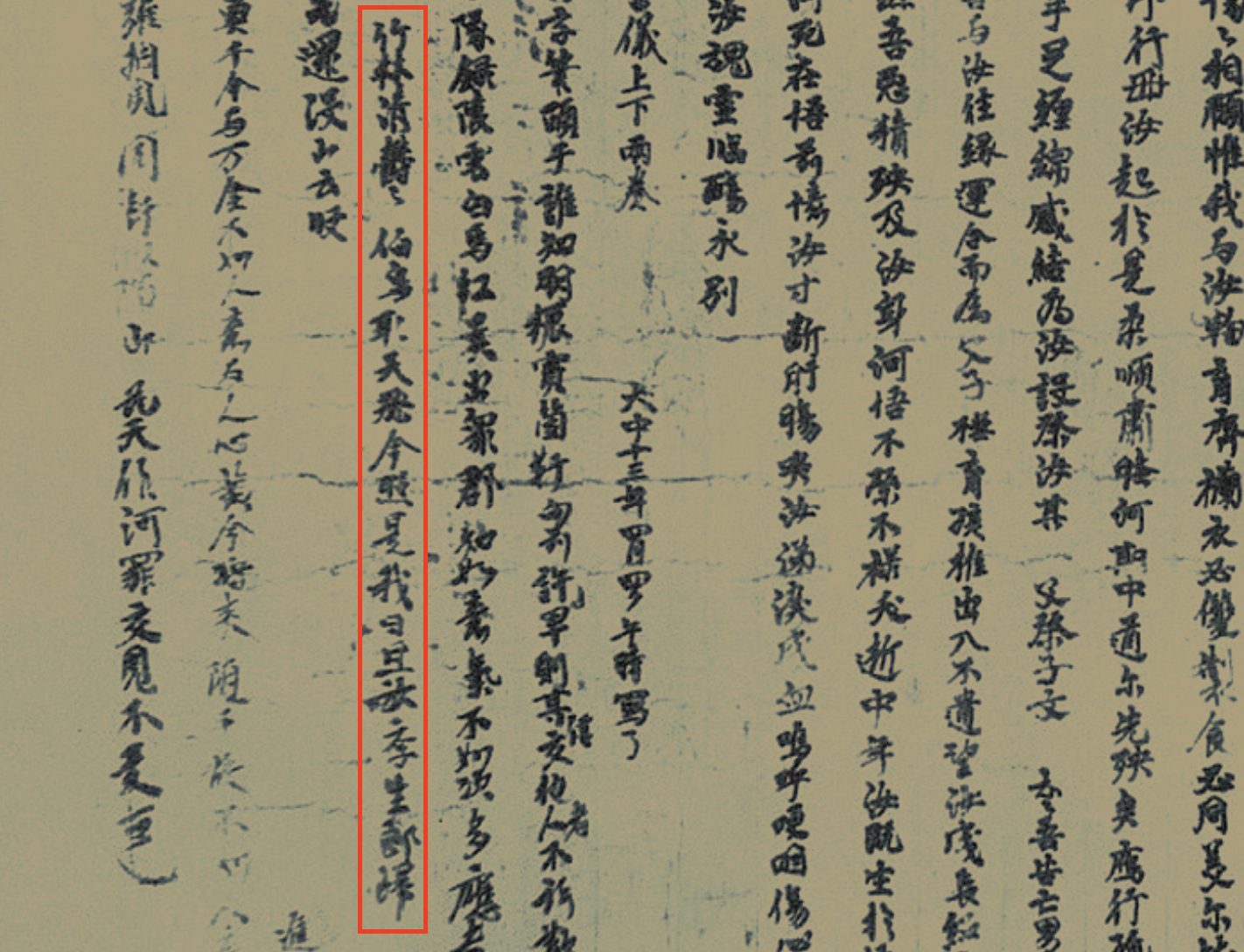

In particular, student poems are somewhat common in Dunhuang manuscripts. Students in the 9th century used to work as part-time scribes, and it seems they often got whiny. So, while doing the book-copying work they would add random poems to the margin or the end when there was white space. The poems had apparently been written by and circulated among local students, and they are so honest that Hu Shih once called them “scribes’ resentful poetry” (see this paper and this monograph if you can read Chinese and want to learn more about Dunhuang student poems). Take the following one for example, which is from a different part of the above-mentioned manuscript (P.2622):

竹林淸鬱鬱/伯鳥取天飛/今照是我日/且放學生郎歸

The bamboo forest is luxuriantly green / and the birds are flying freely in the sky / today is my (holi)day / so let me go home early (my translation)

A shame in Classical Chinese teaching

Supplemental materials like the above can help make ancient Chinese classes more enjoyable, which are currently dominated by classical texts. While Classical Chinese should by all means remain in the center of ancient Chinese teaching, to enhance student enthusiasm some pedagogical creativity is in need 🕺.

Chinese students are required to learn Classical Chinese texts from a very young age (since Grade 5 in my home province, and even earlier if we count in ancient poetry), but apparently most students get no fun out of it. According to a 2003 survey only 20–40% of high school students enjoyed Classical Chinese lessons, and a more recent survey in 2019 also revealed that over 80% of the students in an ordinary Chinese high school found Classical Chinese learning overwhelming. Besides, many students find Classical Chinese even harder to learn than foreign languages.

In my experience, the less-than-ideal status quo in Classical Chinese education in China is at least partly due to the overly conservative methodology. For instance, I find it bizarre that Classical Chinese has never been taught just as a language. It has always been taught as a means to something else instead (e.g., literature, philosophy). The upside of this methodology is that students get to learn more about our history and culture along the way, but its downside is also clear: they never really get to learn the language itself in a systematic way. As a result, students can typically only read Classical Chinese (with the aid of carefully compiled glosses) but not write in it; they can recite famous articles from history but can’t tell why individual sentences are structured the way they are, let alone compose new sentences by themselves. This is a huge shame considering the decadelong effort students are required to put into the subject. 😢

Modernization

Now that we are over two decades into the 21st century, I think it’s time that we made our ancient Chinese classes more fun. Our students are smart and hardworking, and they deserve a more up-to-date way of learning. In fact, similar ideas have been put into practice in Latin teaching. For instance, this American high school teacher adopts a MovieTalk method in her Latin class (see this page for more information on communicative classical language teaching). Similarly, my own undergraduate Latin teacher used to show us a variety of movie clips featuring the Latin language and had even initiated an annual Latin concert. Of course, he still taught us plenty of grammar and left us weekly translation assignments, but the multimodal methodology he adopted made the coursework a lot less intimidating.

I think this kind of modernization is exactly what Classical Chinese classrooms need. Since ancient languages are still human languages, they can surely be taught and learned like other human languages (even Duolingo has a Latin course now). That’s why I used the word “bizarre” above to describe my feelings about current Classical Chinese teaching. In an era where foreign language classrooms have kept up with SLA theory (e.g., task-based language learning, multimodality) and technological advancement (e.g., MOOC, smart phone apps), the reading-and-translation-only mode in Classical Chinese classrooms just feels a bit lazy. 😝

For the remaining content of this post go to Part 2.

Leave a comment