I’m a sci-fi lover, and in the past few years I’ve been deeply impressed by the trilogy Remembrance of Earth’s Past written by the Chinese author Cixin Liu. The novel is more commonly known as “Three-Body” (三體) among its Chinese fans, which is the title of its award-winning first part (English title: The Three-Body Problem). Former U.S. President Barack Obama described the trilogy as “wildly imaginative” and “really interesting,” and Amazon seems to be planning a TV show based on it too—hopefully that’ll come true! Below are the titles of the novel’s three parts together with their published English translations:

- 三體 The Three-Body Problem (translator: Ken Liu)

- 黑暗森林 The Dark Forest (translator: Joel Martinsen)

- 死神永生 Death’s End (translator: Ken Liu)

Three-Body’s epic storyline spans 18.9 million years—from the Cultural Revolution till the end of our universe—and the reading experience is absolutely stunning. I won’t spoil it in case you haven’t read the novel, but the animation below gives a wonderful depiction of some of its key scenes:

What I will write about in this article is the linguistic view in the Three-Body trilogy. Liu explicitly mentions language in a number of places and sometimes even gives it a crucial role to play. In fact I think Liu has infused a complete linguistic worldview into his writing. For ease of reading I’ve split this article into three parts. This post, Part 1, is about my impression of fictional languages in general, and the next two posts, Part 2 and Part 3, will be my commentary on specific language-related bits in the novel.

Language in fiction

There aren’t many language-themed fiction works out there. The only one I know is Ted Chiang’s novella Story of Your Life, which I (probably like many of you) have learned of via its 2016 film adaptation Arrival. More often, language is portrayed in fiction as a background element, such as Tolkien’s Elvish languages and Orwell’s Newspeak.

Linguistic elements in sci-fi are often based on writers’ personal experience. Both Tolkien and Orwell had constructed their fictional languages in a largely Indo-European fashion, with alphabets, words, affixes, and the like. See below for two examples:

- Quenya (a variety of Elvish): elda-r ‘elf-nom.pl’ => High Elves (Elfdict)

- Newspeak: un-proceed ‘imp.neg-proceed’ => Don’t proceed! (Wikipedia)

Chiang, on the other hand, had constructed his Heptapod language—more precisely Heptapod B1—in a much less alphabetic or linear way. It’s not even sound-based! To me its design in the film adaptation is somewhat reminiscent of Chinese ink brush writing. To illustrate, below is the same “word” time in Heptapod B (left) and in Chinese (right).2

The movie’s illustration doesn’t fully match Chiang’s original conception in the novella, but one crucial feature of Heptapod B that both versions make clear is that the combination of meaningful units into “words” and “sentences” in this purely visual language is not linear but two-dimensional. In simpler terms, it’s unlike English, Spanish, or Russian; to some extent like Chinese (especially the ancient scripts), Mayan, or Sumerian; and very much like drawing!🖍

The design difference between Elvish/Newspeak and Heptapod B may be due to the different purposes of the fictional languages; for example, both Elvish and Newspeak are earthly while Heptapod is alien. However, it may also have to do with the linguistic background and/or interests of the authors:

- Tolkien was a native English speaker who knew a number of grammatically complex European languages. According to Helge Kåre Fauskanger’s Introduction to Quenya Tolkien had been inspired by Finnish, Greek, Latin, and Spanish when creating Elvish.

- Orwell was English-speaking too but had a keen interest in Basic English (a controlled language created by Charles Kay Ogden) instead of grammatically complex languages. Basic English had allegedly inspired his creation of Newspeak.

- Chiang was born and raised in the U.S., but his parents are both native speakers of Chinese (Wikipedia), so Chinese plays an important role in his linguistic background and may have influenced his conception of the Heptapod language (though he may well deny this).

Incidentally, another popular sci-fi language Klingon, albeit also alien, feels a lot more similar to Earth languages—especially to the morphologically rich ones (i.e., languages with a lot of grammatical markers). This design may have to do with the fact that its creator Marc Okrand, an English-speaking linguistician, has had a professional interest in Native American languages (especially Mutsun), which also tend to be morphologically rich. For example, Klingon has a special plural marker -Du’ dedicated to body part nouns, and Mutsun has a special suffix -wa for nouns meaning serpent-like creatures.

- Klingon: ghop-Du’ ‘hand-pl.body’ => hands (Wikipedia)

- Mutsun: lissok-wa ‘water snake-n.serp’ => water snake (Okrand 1977, p. 142)3

That Klingon is an earthly alien language is clearly reflected in its grammar. How different is Klingon ghop-Du’ from, for instance, Hungarian kez-ek ‘hand-pl’ or even English hand-s? Well, they refer to the concept “hand” by different names and also use different sounds to convey plurality, but other than these surface differences they follow exactly the same underlying pattern—some element means “hand,” some means plural, and when the two are combined the result is a plural noun meaning “hands.” N.b. the terms plural and noun—in most if not all alien languages imagined by earthlings the grammatical categories are faithfully earthly!

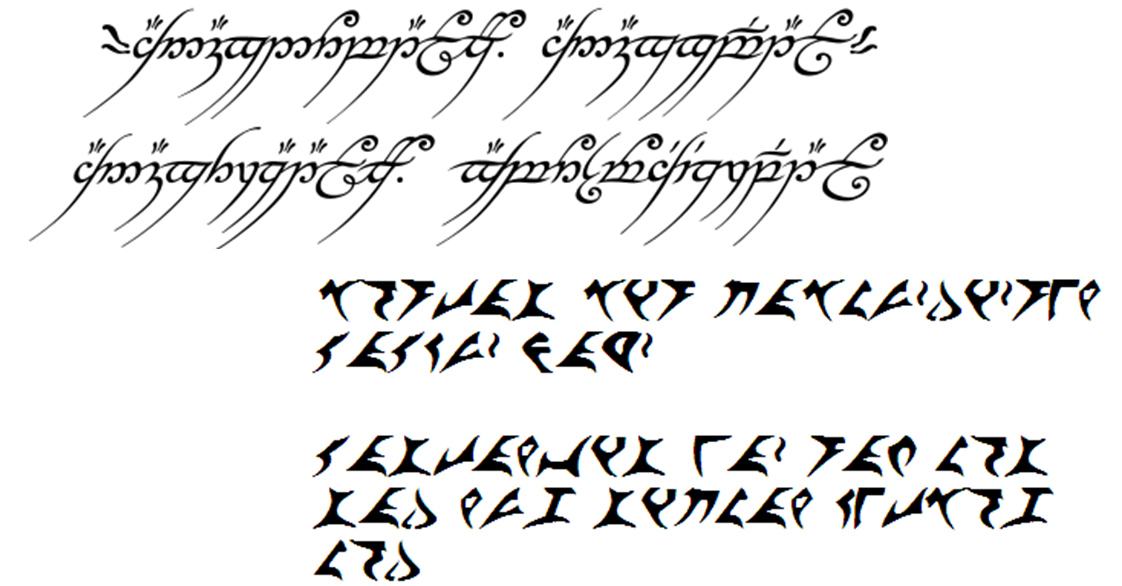

Elvish and Klingon additionally have specially invented writing systems. See below for an overall impression.

Sources: The Lord of the Ring Wiki, Wikimedia Commons

However, these exotic-looking scripts are actually as “ourworldly” as their corresponding spoken languages. Between the two, the Elvish script (called Tengwar) is more finished, but both systems are still phonemically oriented—that is, they try to write down the individual sounds that make up words. In this respect, they aren’t that different from real alphabets used on Earth, and their exotic appearance probably has more to do with their deliberately calligraphic font styles and their non-Phoenician (especially non-Latin) nature. In fact real non-Phoenician alphabets—such as Hangul for Korean and Bopomofo for Chinese (traditional)—may look no less exotic to someone accustomed to reading familiar Phoenician alphabets (e.g., Latin, Greek, Cyrillic). See below for a comparative illustration.

| Real | Phoenician | Latin | a | o | p | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | α | ο | π | τ | ||

| non-Phoenician | Hangul | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅂ | ㄷ | |

| Bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄛ | ㄆ | ㄊ | ||

| Fictional | Tengwar | |||||

| KLI pIqaD | ||||||

All the above examples together suggest that a person’s own language experience may shape his ideas and imagination about language. And the linguistic imagination of Homo sapiens as a whole is also limited by the overall shape of human language. Well, this sounds a bit Sapir-Whorfian, but I’ll leave that topic to a future post.😉

Your world is defined by your language.

Click here for Part 2 of this article.

2.↩ The character in the picture is 宙 in the cursive or “grass” script. It's an ancient and literary way of saying “time” and in Modern Chinese is only seen in the compound word 宇宙 ‘universe’, which literally means “space-time.”

3.↩ Okrand, Marc 1977. Mutsun Grammar. UC Berkeley dissertation.

Leave a comment