So I ended up using category theory in my linguistics dissertation. How this happened is a long story. Basically I stumbled into a promising-looking toolkit and learned it, without realizing how audacious a decision it was for someone who hadn’t received university-level math education at all. Universities in China usually make at least one math course compulsory but (un)fortunately I chose a foreign language major and had the exemption…

Two positive messages

But now that I’ve gone through the process, I can share two positive messages with my fellow linguisticians who are also from a purely language/humanities background:

- If there’s one branch of math that isn’t philosophically alien to linguisticians, at least on a big-picture level, it’s category theory.

- Category theory is learnable even if you know nothing about the usual university math topics (calculus, linear algebra, etc.). All you need is readiness for abstract thinking, which linguisticians are pretty good at.

A bonus of learning category theory is that once you know it, many other mathematical branches as well as some nonmathematical subjects—such as abstract algebra, type theory, and functional programming—become a lot less formidable. In other words, category theory is like a “shortcut” to understanding complex stuff. On the one hand, it’s so abstract that everything else just looks, well, less abstract. On the other hand, it successfully demonstrates that many complex conceptual constructs are actually complex in the same way.

So, even if you don’t plan to use category theory in your own research (yet), knowing its basics can still add a valuable item to your skill set. Forbes recently published an article entitled “The future will be formulated using category theory.” It’s controversial among mathematicians but nevertheless reflects the increasing interest of the current world—academia and industry alike—in a theory that has long been labeled “abstract nonsense.”

Why category theory isn’t alien to linguisticians?

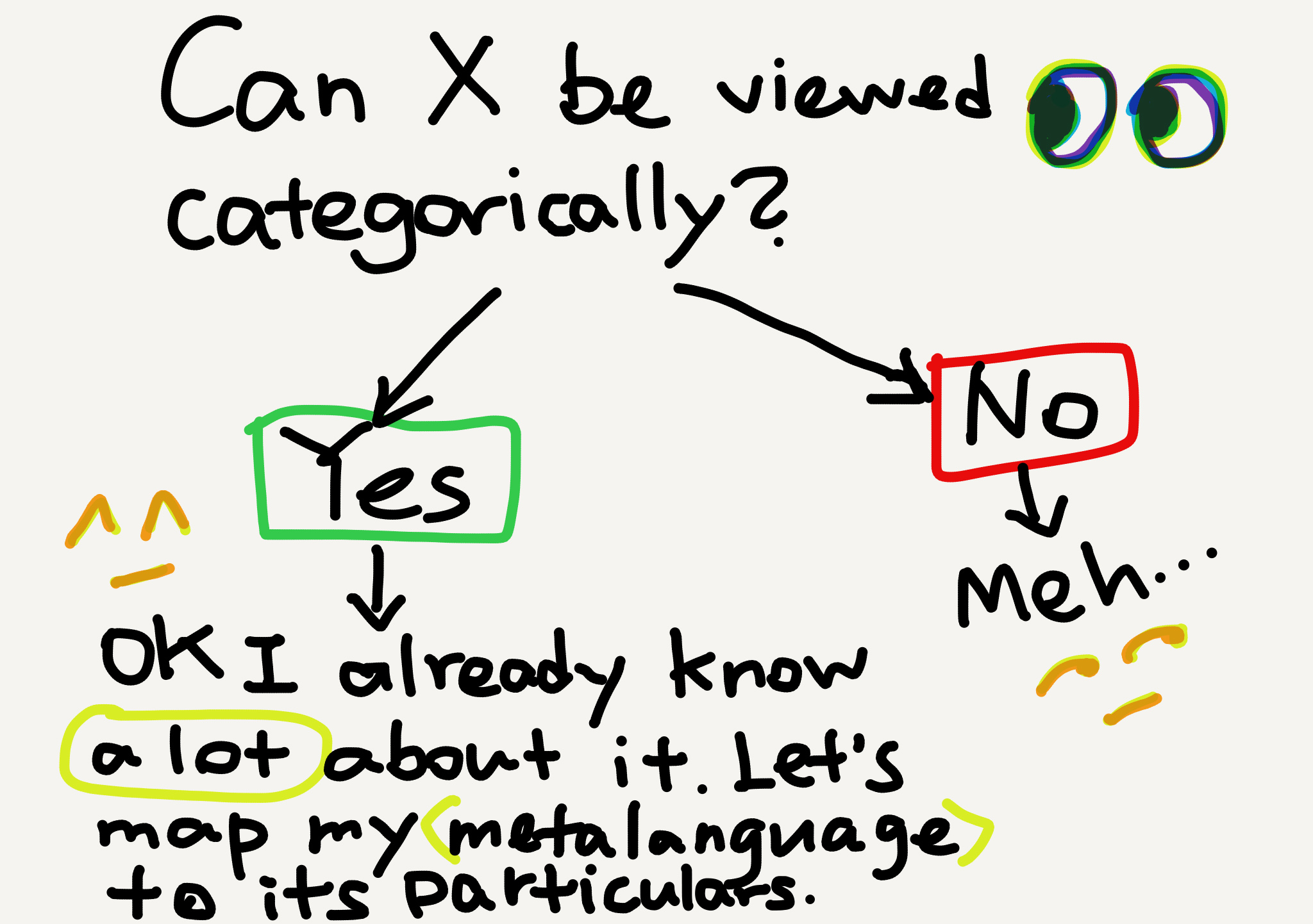

Let me use a picture to illustrate the usual way categorists approach new (sub)disciplines (replace X with any subject name or topic).

Sounds familiar, right? In my Aug 10 post I mentioned a similar approach taken by linguisticians in learning languages—by mapping the particular grammars to a universal, abstract metalanguage. This universal metalanguage, so to speak, is linguisticians’ “category theory.”

Besides, in linguistics there often exist competing paradigms within the same (sub)field, with different assumptions, methods, and communities. In syntax, for instance, there are government and binding theory, lexical functional grammar, head-driven phrase structure grammar, categorial grammar, dependency grammar, and so on and so on. Students worldwide aren’t always taught all these paradigms—which paradigm they get to learn depends on which institute they go to—and even less often told why linguistics, a modern subject increasingly portrayed as a branch of science, is so full of competing schools and traditions.

But if we take a step back, what all linguistic paradigms are trying to do is really the same thing: modeling the grammatical system of human language and making predictions about it. Given such a shared goal, there must be a certain level of abstraction where the different paradigms all become “one.” For example, every syntactic theory needs some component to describe the basic combinatorial property of human language (e.g., sentences are made up of individual words). Chomsky calls this property “merge,” Pollard and Sag call it “unification,” and Lambek calls it “division”;1 but at a higher level of abstraction these all amount to the same thing, just as different terms used in particular grammars may correspond to a single metalinguistic notion, and constructs in different mathematical subfields may correspond to a single “metamathematical” notion.

Basically category theory is mathematicians’ best medium language (at least categorists think so). For those who know it, it’s like a fast track to grasping particular fields and theories.

Category theory is a “theory of everything.”

Why am I writing this blog series?

Why do I want to turn my study notes into a blog series? This series is certainly not for the mathematically experienced. There are plenty of textbooks on the subject and I don’t attempt to “show off my proficiency with the axe before the master carpenter” (班門弄斧), as the ancient Chinese proverb goes.

Rather, I merely want to organize my knowledge and record my journey of learning category theory from a linguistician’s perspective. I also want to demonstrate with my own experience that category theory is not only learnable but actually makes a lot of sense to linguistically oriented minds!

There are many things that I wish I had known when I first started learning category theory. Sadly I can’t time-travel to tell myself, but if someone happens to be in a similar situation, I hope my blog posts could be of some subsidiary help.

Since this isn’t a systematic tutorial, I won’t go into much mathematical detail (though when needed I’ll try to provide links to sources that I’ve found illuminating), nor will I go through textbook topics one by one. Instead, I’ll try to explain category-theoretic concepts that had puzzled me in a way that I wish I had seen a year ago. This isn’t easy because I need to recollect my old thoughts and feelings, but it’s certainly a good writing exercise. I’ll have fun, and hopefully so will you. 😃

Leave a comment