Monoid is one of those concepts that are extremely simple, extremely useful, and can at the same time be extremely confusing. It was one of the first concepts in category theory that I had learned but also one of the very last to click. My “digestion” took several months, and apparently I’m not the only one finding the concept mind-racking; see this, this, and especially this StackExchange thread for examples. Eugenia Cheng makes the following comment in her book Cakes, Custard + Category Theory (or How to Bake Pi if you’re in the U.S.):

I sat for days thinking about it and feeling like my brain was popping out of my head, just like when I was a child and thinking about a graph for the first time in my life. And the fact that a one-object category is exactly a monoid is now so obvious to me that I know I am definitely cleverer now than I was then. (p. 27)

I have exactly the same feeling.

My confusion

I’m not sure what had confused Cheng, but for me it was the big jump from a set-theoretic conception of monoid to a category-theoretic conception. Set-theoretically, a monoid is just an algebraic structure with a single associative binary operation and an identity element; namely, it’s a semigroup with identity (Wikipedia). There’s nothing confusing in this definition, and examples are also easy to find.

- The natural numbers (including zero) form a monoid under addition, because for any natural numbers $a, b,$ and $c$ we have $(a+b)+c = a+(b+c)$ and $a+0 = 0+a = a$. (Moreover this is a commutative or abelian monoid, because $a+b = b+a$.)

- The positive integers form a monoid under multiplication, because for any positive integers $a, b,$ and $c$ we have $(a \times b)\times c = a\times (b\times c)$ and $a\times 1 = 1\times a = a$. This is also an abelian monoid because $a\times b = b\times a$.

- The set of all finite strings over a fixed alphabet forms a monoid under string concatenation, because for any strings

a,b, andcin the set we have(a ++ b) ++ c = a ++ (b ++ c)anda ++ e = e ++ a = a(whereeis the empty string). This monoid isn’t abelian, because string concatenation is direction-sensitive (e.g.,"coco" ++ "nut" != "nut" ++ "coco").

The categorical perspective on monoids is rather different. A most conspicuous difference is the much simpler definition:

A monoid is, essentially, the same thing as a category with a single object. (Wikipedia)

If the Wikipedia definition is too condensed, let’s turn to a few published textbooks:

- CWM, p. 11 (Mac Lane 1998)

A monoid is a category with one object. Each monoid is thus determined by the set of all its arrows, by the identity arrow, and by the rule for the composition of arrows. Since any two arrows have a composite, a monoid may then be described as a set $M$ with a binary operation $M\times M \rightarrow M$ which is associative and has an identity (= unit). Thus a monoid is exactly a semigroup with identity element.

- Topoi, pp. 31–32 (Goldblatt 2006)

A monoid is a triple $\mathbf{M} = (M, *, e)$ where (i) $M$ is a set, (ii) $*$ is a binary operation on $M$ … that is associative …, (iii) $e$ is a member of $M$, the monoid identity …. Any monoid $\mathbf{M}$ gives rise to a category with one object …. We take the object to be $M$, the arrows $M \rightarrow M$ to be the members of $M$, and put $e = 1_M$. Composition of arrows $x,y\in M$ is given by $x\circ y = x* y$. Conversely, if $\mathcal{C}$ is a category with only one object $a$, and $M$ is its collection of arrows, then $(M, \circ, 1_a)$ is a monoid.

- Category Theory, p. 11 (Awodey 2010)

A monoid is a set $M$ equipped with a binary operation $\cdot\colon M\times M \rightarrow M$ and a distinguished “unit” element $u \in M$ such that for all $x, y, z \in M, x\cdot(y\cdot z) = (x\cdot y)\cdot z$ and $u\cdot x = x = x\cdot u$. Equivalently, a monoid is a category with just one object. The arrows of the category are the elements of the monoid. In particular, the identity arrow is the unit element $u$. Composition of arrows is the binary operation $m\cdot n$ of the monoid.

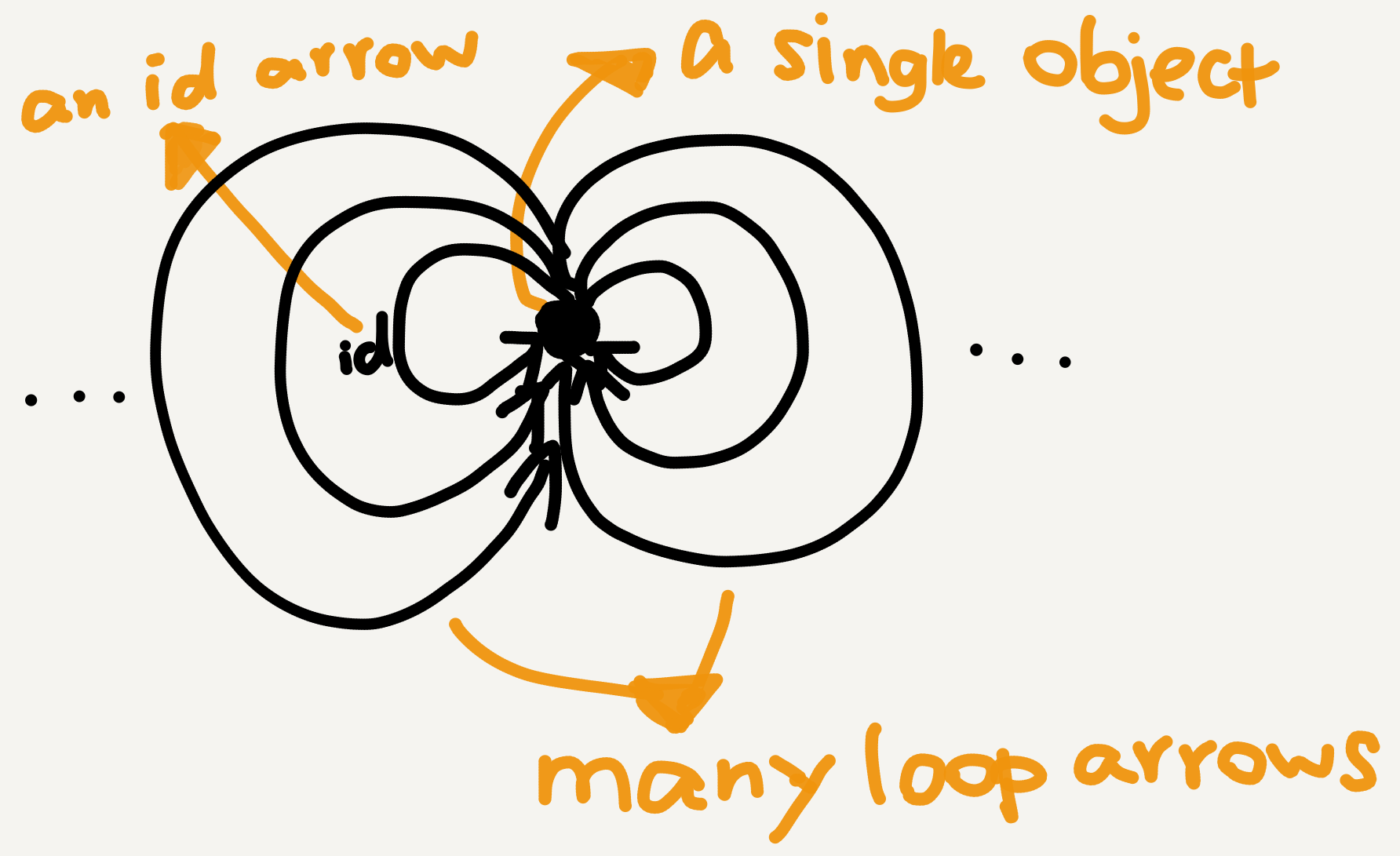

So, basically a categorical monoid is the following picture:

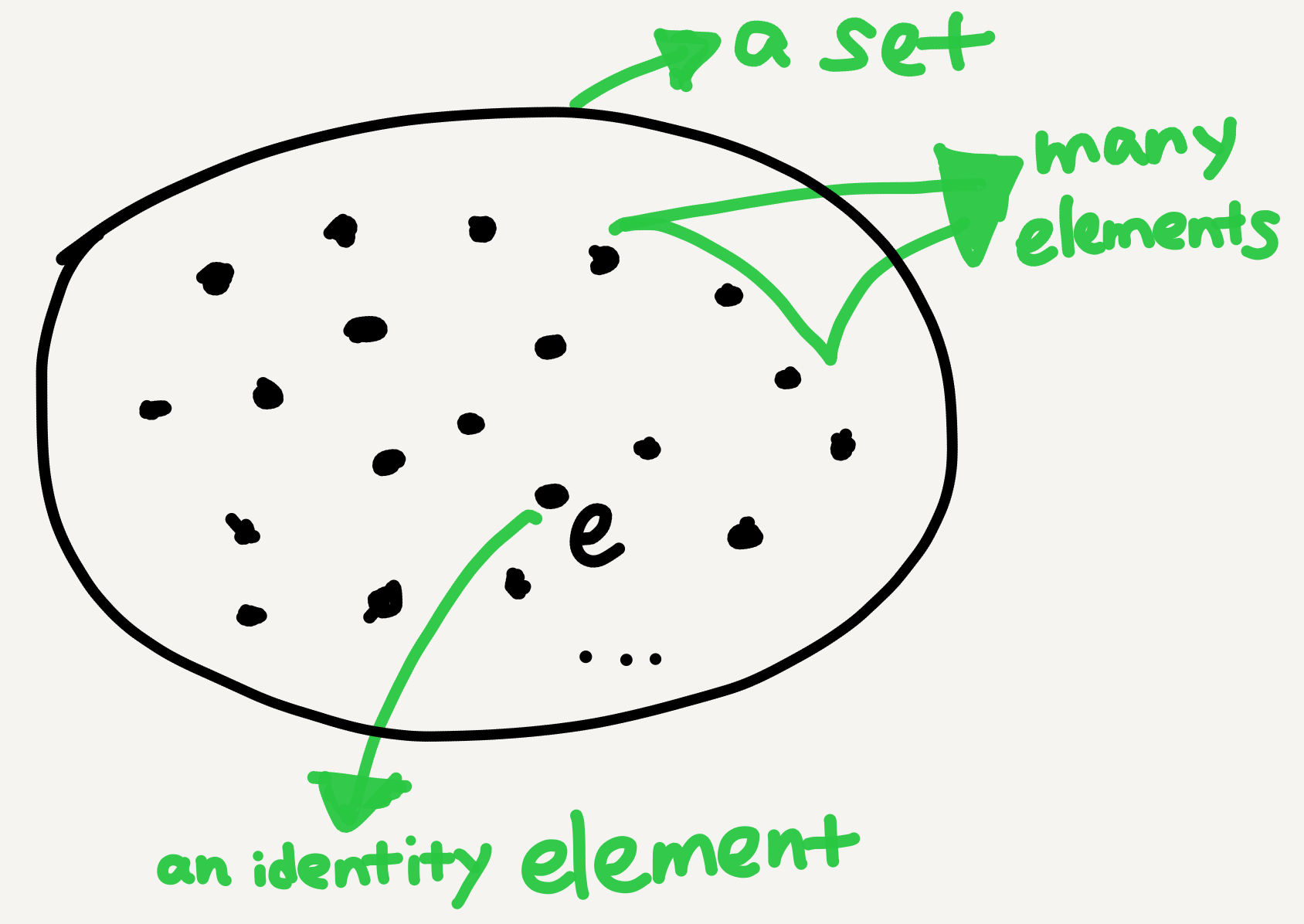

By comparison, a set-theoretic monoid is the following picture:

Note how different the pictures are! When we switch from the set-theoretic view to the category-theoretic view, the essential switch is to view the underlying set in the algebraic monoid as the arrow collection in the categorical monoid—both are closed under a binary operation and have an identity member. My main source of confusion—and also that in the above-mentioned StackExchange threads—is the single object in the categorical view, which is absent in the algebraic view. Why is it confusing?

- The single object is left undefined (or unspecified). Usually when defining a category the first thing to do is specify what its objects are. For instance, in the category $\mathbf{Set}$ the objects are sets, in the category $\mathbf{Grp}$ the objects are groups, and in the category $\mathbf{Pos}$ the objects are posets (= partially ordered sets). But what’s the single object in a monoid? We don’t know, at least not from the above-listed definitions.

- Following 1, this seems to suggest that the category termed “monoid” is fundamentally different from the usual categories, in that unlike $\mathbf{Set}$, $\mathbf{Grp}$, etc., a monoid category isn’t named after its object type.

- It’s unclear how the algebraic operation corresponds to the categorical composition. Take the natural numbers under addition for example. The usual way to categorify this monoid is to “name” or “label” the arrows in the one-object category with the natural numbers, whereby arrow composition becomes arithmetic addition. Intuitively, however, named arrow composition and arithmetic addition are fundamentally different operations. While it’s self-evident that arithmetically $1+2=3$, it’s not evident at all why the named arrow “1” composed with the named arrow “2” should give us the named arrow “3.” After all, when conceived as name labels the “numbers” lose their ordinary mathematical definitions. If so, what guarantees that we have ●$\xrightarrow[]{1}$●$\xrightarrow[]{2}$● $\equiv$ ●$\xrightarrow[]{3}$● in the category (other than the arbitrary stipulation “we want it so”)? If the definition is just a stipulation, then why can’t we stipulate, say, that “1” “+” “2” $\equiv$ “5”?

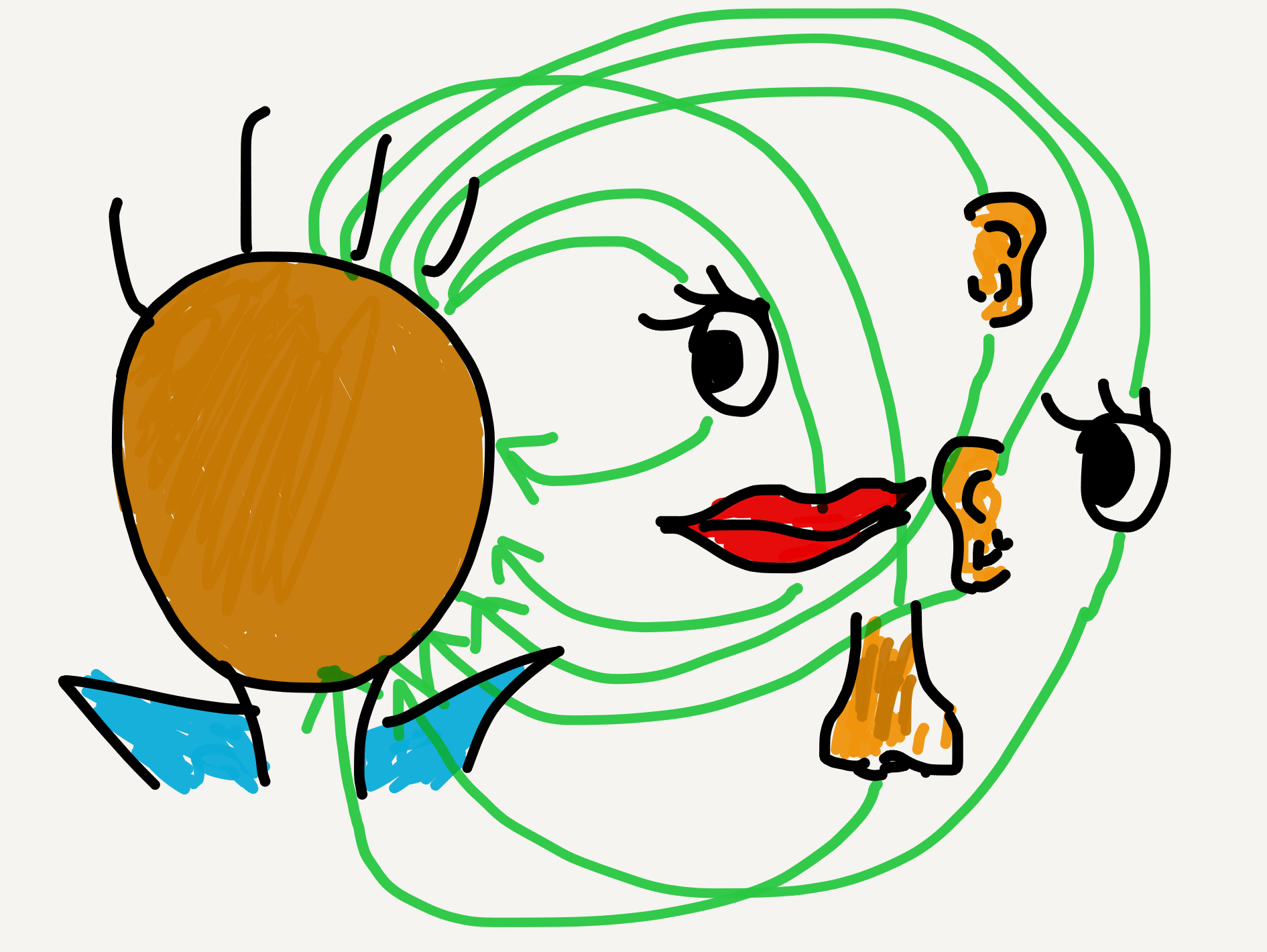

- In Goldblatt’s formulation the single object is viewed as the underlying set of an algebraic monoid while the arrows are viewed as its elements. This feels weird (at least for the uninitiated) because it literally says that the set’s elements live outside the set container… Upon reading Goldblatt’s words, the following picture popped up in my head:

How scary!😱

My understanding

I can’t remember when or how I eventually understood the categorical conception of monoid. Perhaps I just got exposed to category theory long enough and picked up the implicit assumptions and conventions in the field. Anyway, below is how I understand the issue now.

- The single object in a categorical monoid is left unspecified because it’s unimportant. It’s only there to “support” the arrows. We can give it any name we want; for example, “Apple,” “Banana,” or “Single Object.” Its name doesn’t affect the monoid nature of the category.1

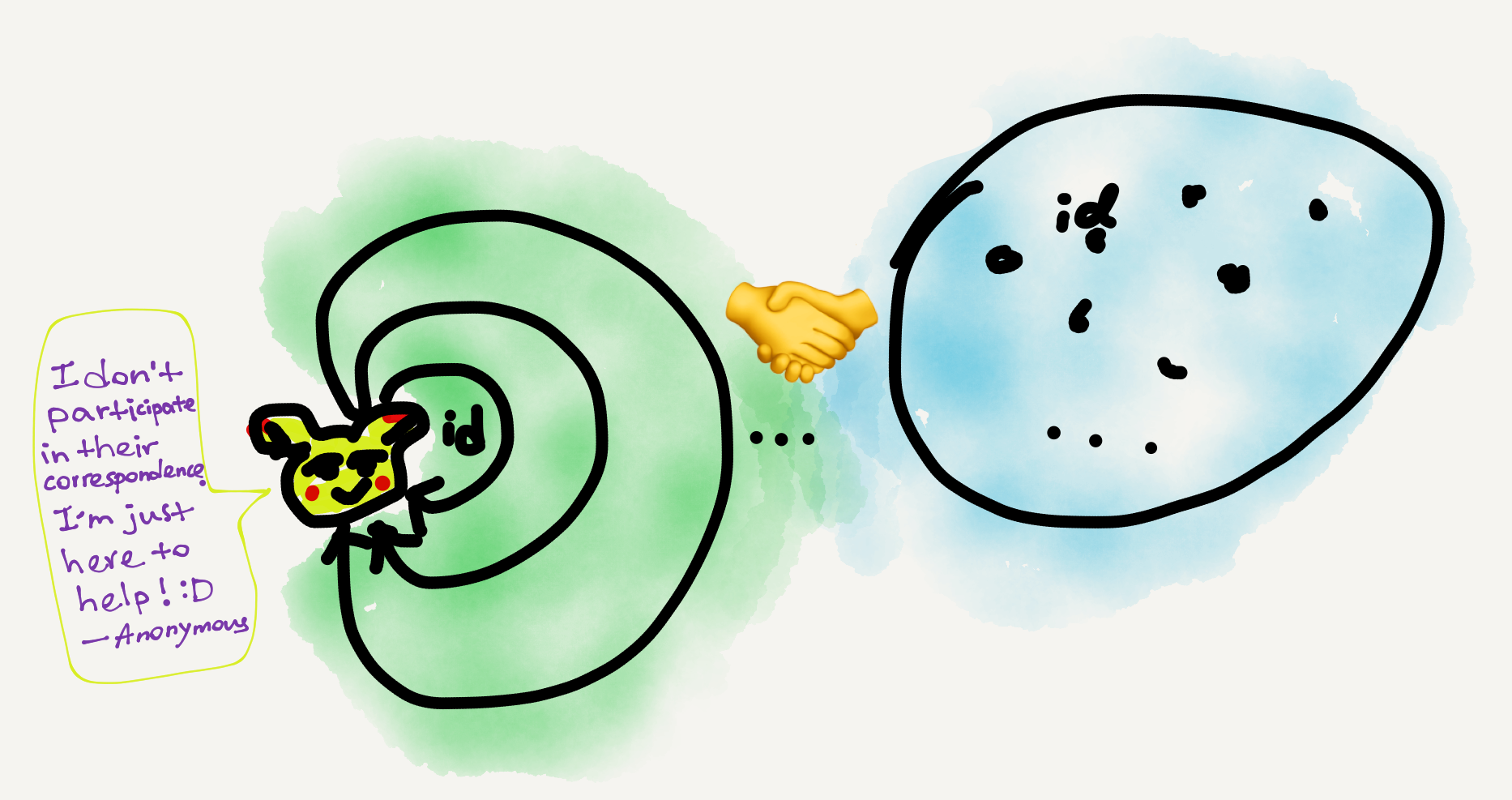

- The relationship between the single object and the arrows can’t be viewed as one of a set and members (pace Goldblatt). When we choose to view a monoid categorically, we must temporarily forget its set-theoretic definition. So, in the single-object category there’s neither a “set” nor any “element.” If you really want to connect the two perspectives, the categorical “counterpart” of the the set-theoretic monoid is all and only the arrow collection; the single object stays out of the story.

The categorical monoid (left) merely partly corresponds to the set-theoretic monoid (right). The two perspectives are not “verbatim translations” of each other. - When viewing the natural-number-under-addition monoid categorically, that “1” “+” “2” $\equiv$ “3” in the category is not at all logically derived (or derivable); it’s just our chosen definition instead—sort of a mnemonic to show human readers how the arrow composition works. Even if we don’t give the arrows any labels they still compose in the same way—it just becomes harder for human readers to perceive and keep track of.

- We may well choose not to define “1” “+” “2” $\equiv$ “3” in the category but define, say, “1” “+” “2” $\equiv$ “5” instead. Everything would still work as long as we can make our new addition rule coherent. Most human beings choose to define “1” “+” “2” $\equiv$ “3” simply because it reflects how arithmetics works in our world. But maybe in some parallel universe the addition rule is indeed $1+2=5$. Who knows!

Besides, an interesting point in my confusion is the realization that “the category termed ‘monoid’ is fundamentally different from the usual categories.” It turns out that monoid is a much more general concept in category theory than categories with specific object types. As Mac Lane states in CWM:

For any category $C$ and any object $a\in C$, the set $hom(a,a)$ of all arrows $a\rightarrow a$ is a monoid. (p. 11)

In particular, this means that every category object is a monoid, even if it has only one loop arrow (i.e., the id arrow)—algebraically that is just the trivial monoid $\{e\}$, with $e$ being the identity element.

There’s still much more to say about monoid. In fact the concept of category itself is sort of like a generalized monoid (see, e.g., Awodey 2010, p. 12). But that’s way beyond the scope of this post.

My wish

I wish that future category theory textbooks targeting nonmathematician beginners can make the various disciplinary assumptions and conventions more explicit. Sometimes something that is too obvious for a mathematician to bother spelling out can cause much struggle to an interested layman. It’s not necessarily because the mathematical concepts themselves are hard to understand but rather due to the fact that people with different levels of mathematical experience or “maturity” don’t share the same “background discourse,” to borrow a linguistic term. The same applies to introductory textbooks in other disciplines, of course.

Leave a comment