In the previous post I introduced the historical and cultural background of the ancient Chinese divination book I Ching ‘the Classic of Changes’. In this post I go on to introduce the structural components of the I Ching’s symbolic system.

Hexagrams

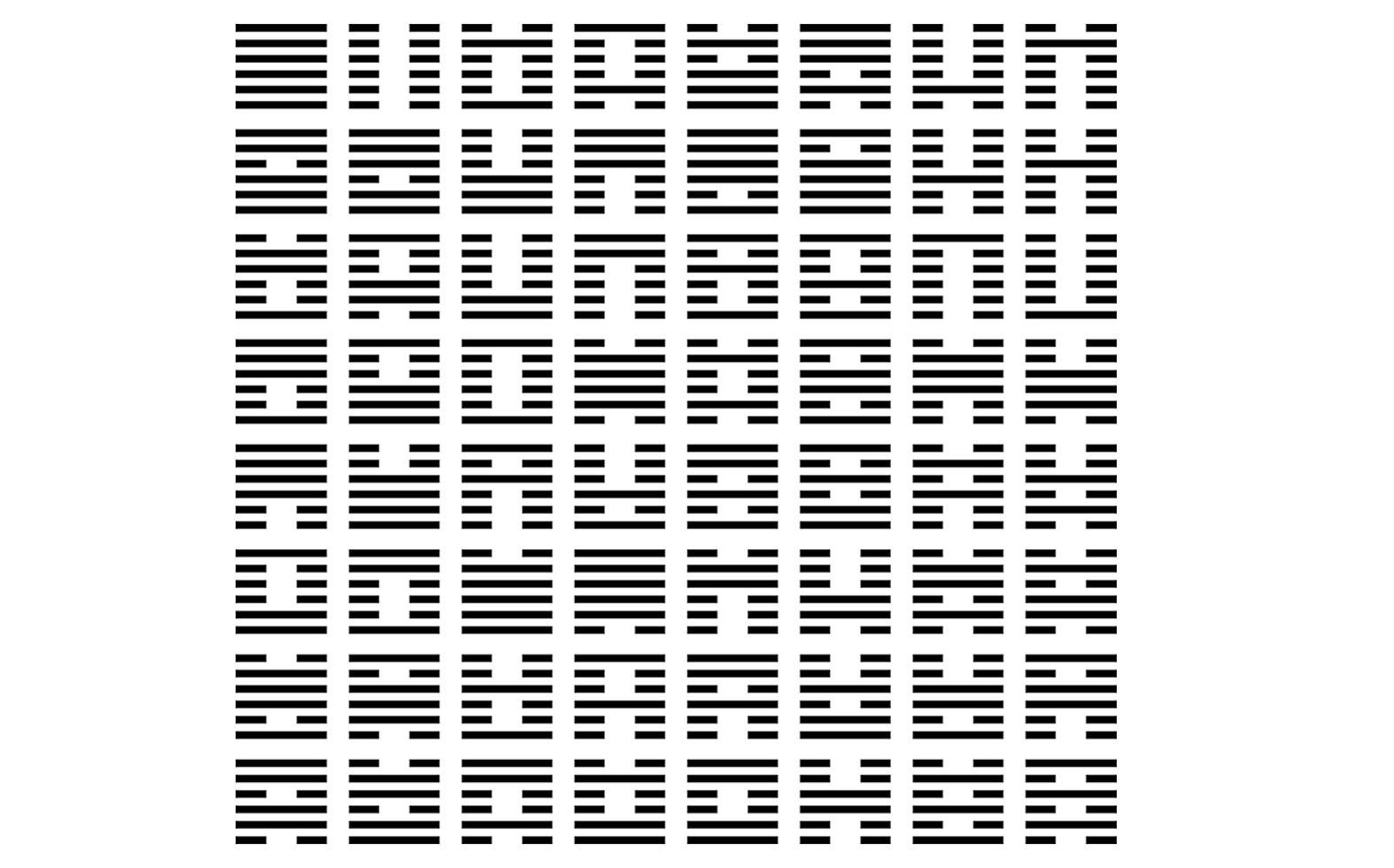

The I Ching uses hexagrams to model situations in the universe. There are altogether sixty-four hexagrams, which allegedly cover everything a human may experience in his life. These also constitute the entire content of the book, with each hexagram taking up a chapter.

At the lowest structural level, a hexagram is made up of two basic types of lines, the solid or yang line ⚊ and the broken or yin line ⚋ (not sure why the unicode renderings of the two symbols look like underscores). These are called the two primary forces or liang yi ‘two modes’ (兩儀). The building of hexagrams from yin and yang is essentially a matter of combinatorics (there’s an entire book on this published by UC Berkeley). Since there are two basic line types, the number 64 is just 26.

Each I Ching hexagram is a complex symbol with multilayered structures. The most salient structure is the stacking of two trigrams; for instance, ䷂ = ☵ + ☳. The trigrams, together with their basic meanings, are I Ching’s way of categorizing various basic phenomena and relationships. The archetypal or design category for the trigrams is that of nature, in which the eight trigrams respectively represent heaven, lake, fire, thunder, wind, water, mountain, and earth (in Fuxi’s order).

| Trigrams | ☰ | ☱ | ☲ | ☳ | ☴ | ☵ | ☶ | ☷ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | 🌌 | 🏖 | 🔥 | ⚡️ | 🌪 | 💦 | ⛰ | 🌏 |

Trigrams

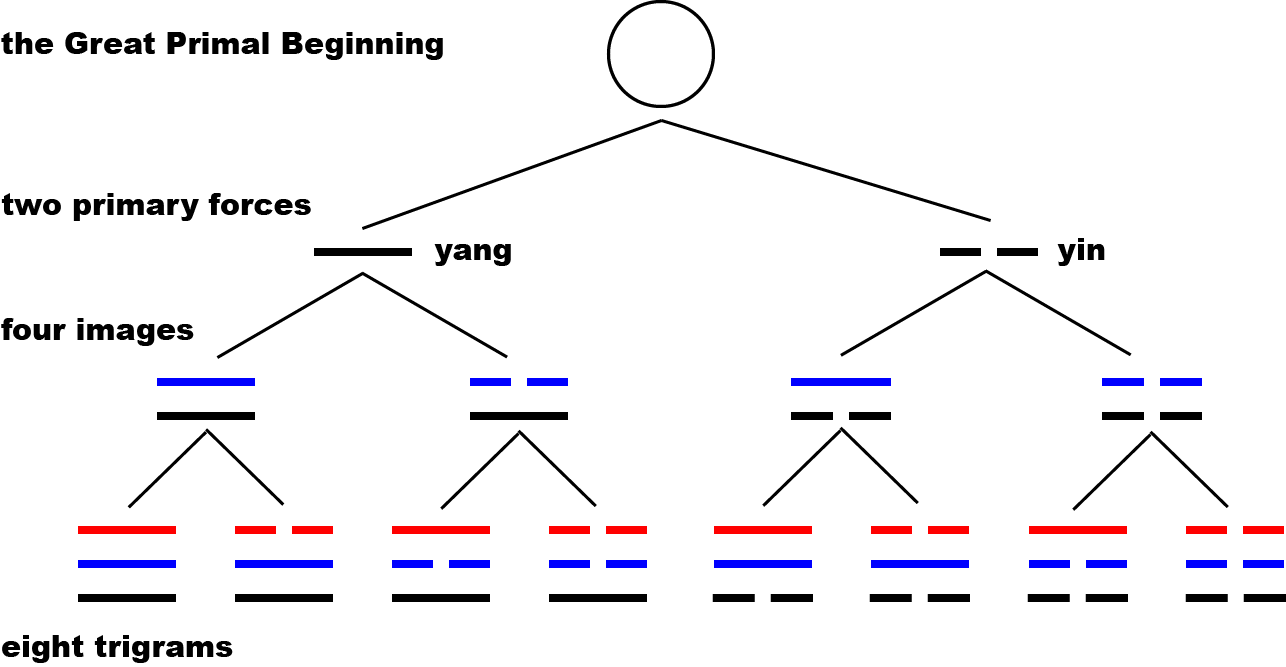

Like the hexagrams, the trigrams are also made up of the two primary forces, hence their total number 8 (23). The sixty-four hexagrams can thus be alternatively conceived as 8×8 (instead of 26). There’s also an alternative (and more dynamic) way to derive the eight trigrams—by successively dividing the initial, biggest category of the universe (called the tai chi 太極 and variously translated as the Great Primal Beginning or the Supreme Ultimate) into two subcategories. The Confucian commentaries contain a famous quote about this:

There is in the Changes the Great Primal Beginning. This generates the two primary forces. The two primary forces generate the four images. The four images generate the eight trigrams.

(易有太極,是生兩儀,兩儀生四象,四象生八卦。)

— The Great Commentary (Wilhelm/Baynes’ translation)

The process can be more clearly seen in a binary branching tree:

The binary division of the tai chi can in principle go on forever, but King Wen thought the sixty-four hexagrams were already enough to cover all situations in the universe. There have been attempts in history to continue the division. One such attempt is found in Jiaoshi yilin ‘Forest of Changes of the Jiao Clan’ (焦氏易林) (the book surprisingly exists on Amazon in English), authored by Jiao Gong (焦贛) in the first century B.C.E. Jiao’s book contains altogether 4096 (64×64) twelve-line diagrams, each consisting of two stacked hexagrams. However, it is difficult to see the usefulness of further extensions like this, as Zhu Xi (1130–1200 C.E.) commented in Yixue qimeng ‘Introduction to the Study of the Changes’.

If from the 12-line diagrams we continue generating odd and even lines, eventually we come to 24-line diagrams, for a total of 16,777,216 changes. Taking 4,096 and multiplying it by itself also gives this sum. Expanding this we do not know where it ultimately ends. Although we cannot see its usefulness, it is sufficient to show that the Way of Change is indeed inexhaustible.

(若自十二畫上,又各生一奇一耦,累至二十四畫,則成千六百七十七萬七千二百一十六變,以四千九十六自相乘,其數亦與此合。引而伸之,蓋未知其所終極也。雖未見其用處,然亦足以見易道之無窮矣。)

— Yixue qimeng, pp.26–27 (Adler’s translation)

Old and young

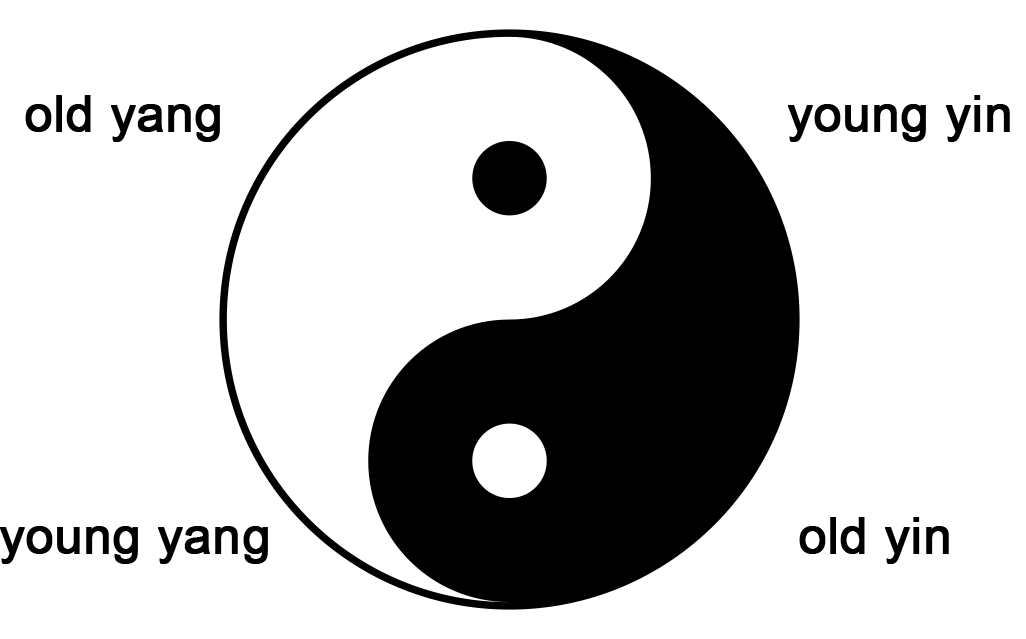

The design of the I Ching system is such that each symbol at each level of the binary branching tree has a dedicated name; that is, each available symbolic category is actually used in divination. The names of the eight trigrams were shown in the previous post, and the names of the sixty-four hexagrams are simply the chapter names of the I Ching. As to the four images, they are respectively named old yang (⚌), young yang (⚍), old yin (⚏), and young yin (⚎). The two young images are in a stable state whereas the two old images are unstable and about to change to their opposite forces. Importantly, the transition between yin and yang is gradual rather than discrete, as can be clearly seen in the tai chi liang yi tu ‘picture of the great ultimate and the two primary forces’ (太極兩儀圖), where the young forces are slimmer than the old forces and the old forces carry “embryos” of the opposite forces.

The names of the four images are also used to distinguish the four types of lines referenced in I Ching divination; that is, the two basic lines (young) plus two changing or moving lines (old). The moving lines are important because they are what give rise to hexagram changes.

Hexagram generation

As I mentioned in the previous post, there are two main methods of generating natural numbers in I Ching divination: the older yarrow stalk method and the simpler three-coin method. I won’t go into the step-by-step procedures here; see the following sources if you’re interested.

- Online resources:

- Books (translations of the I Ching with divination guidance):

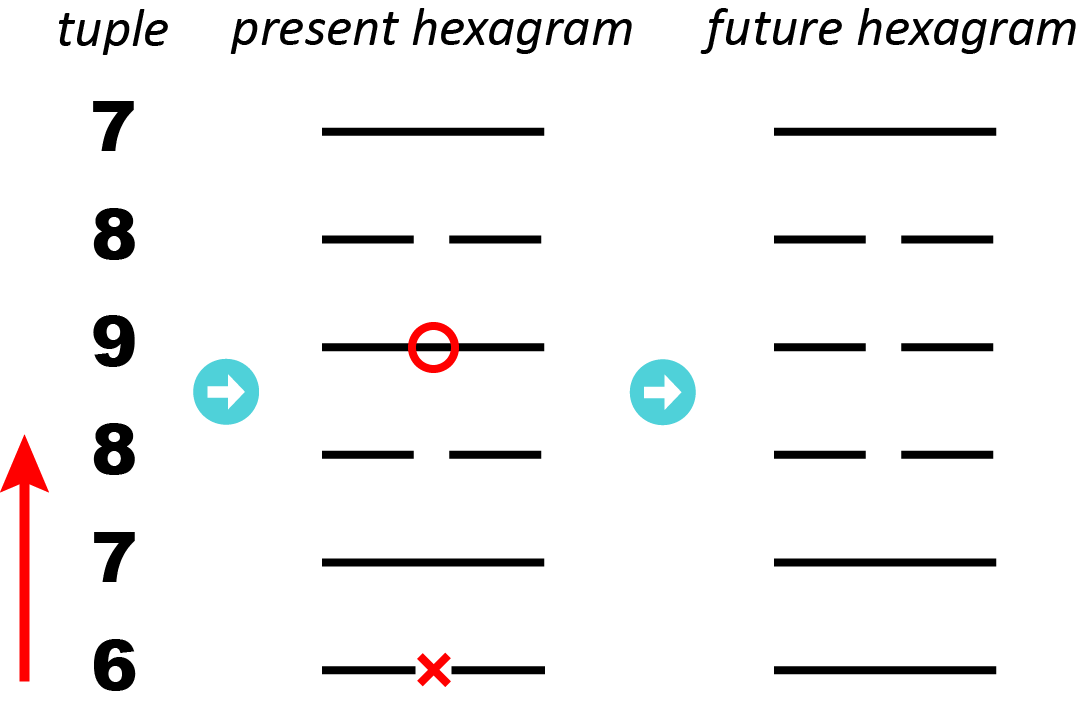

What I’d like to introduce here is how to build hexagrams from random numbers. Imagine we’ve followed either method above and gotten six whole numbers between 6 and 9 (inclusive)—note that these are the only possibilities if we’ve followed the divination procedure correctly. I write the six numbers in a tuple because the order in which they are obtained matters. Below is an example.

tuple1 = (6, 7, 8, 9, 8, 7)

The six numbers in the tuple correspond to the six lines in a hexagram from bottom up (the direction is important). The mapping between the two obeys four rules. For each number in the 6-tuple:

- draw a broken line (⚋) if the number is 6 or 8;

- draw a cross (✕) over the broken line if it is 6;

- draw a solid line (⚊) if the number is 7 or 9;

- draw a circle (◯) over the broken line if it is 9.

The hexagram thus generated is the present hexagram. It is one half of our divination basis; to get the other half we need to follow two more rules. For each line in the present hexagram:

- change it from broken to solid if it has a cross;

- change it from solid to broken if it has a circle.

Applying these two rules to the entire hexagram will give us a new hexagram, which is called the future hexagram. If there are no 6s or 9s in the present hexagram, then the present hexagram itself forms the divination basis. As an example, tuple1 gives rise to the following two hexagrams:

present_hexagram1 = ䷿

future_hexagram1 = ䷨

In case the unicode hexagrams are a bit too tiny to be legible, I’ve created a magnified illustration of the mapping process.👇

Leave a comment