Monogram level

Finally, in the interpretation of divination results we must sometimes take certain monograms (i.e., individual lines) into account as well. The most important monograms are the changing lines (sometimes translated as “moving lines”), so I’ll start with them.

Changing lines

Recall that the Classic of Changes is all about changes. Therefore, the changing lines in a present hexagram, if any, are of special importance, for they are what give rise to the future hexagram—or in less mystical terms, what connect two particular hexagrams out of the total sixty-four.

Since which line(s) are moving is dictated by chance, the result of I Ching divination is highly personalized (there are altogether 64×64=4096 present/future hexagram combinations!). That’s what distinguishes I Ching divination from other types of symbolomancy divination such as that by tarot cards.

No other symbolomancy method … has separate meanings for each component of a card’s picture. The card/symbol is what it is. … This is the great asset of the I Ching. Its inherent flexibility allows for “tailoring” the specific message to you.

— Divination Lessons website

- Nǐ biànguà yě tài kuài le.

(你變卦也太快了。)

"You change your mind too fast."

The I Ching has a dedicated section for changing lines in each chapter. The two changing lines in wei chi are the first and the fourth line from bottom up. They hold the following messages for the questioner:

Line 1 (⚋ → ⚊): He gets his tail in the water. Humiliating.

Line 4 (⚊ → ⚋): Perseverance brings good fortune. Remorse disappears. Shock, thus to discipline the Devil’s Country. For three years, great realms are awarded.

Again the statements are abstruse but the gists are clear. They basically say that there are two crucial factors in the development from wei chi to sun: haste in times of disorder and perseverance in times of struggle. And the questioner should pay extra attention to these factors.

Now, does that mean the present situation won’t change if the questioner deliberately ignores these factors? I’m not in a position to give a definite answer. The truth is, result interpretation has been the most difficult part of I Ching divination for millennia, even for professional soothsayers. When interpreting divination results, all layers of meaning must be taken into account, perhaps with different weights. There’s actually much controversy on this; see this page for a comparative introduction.

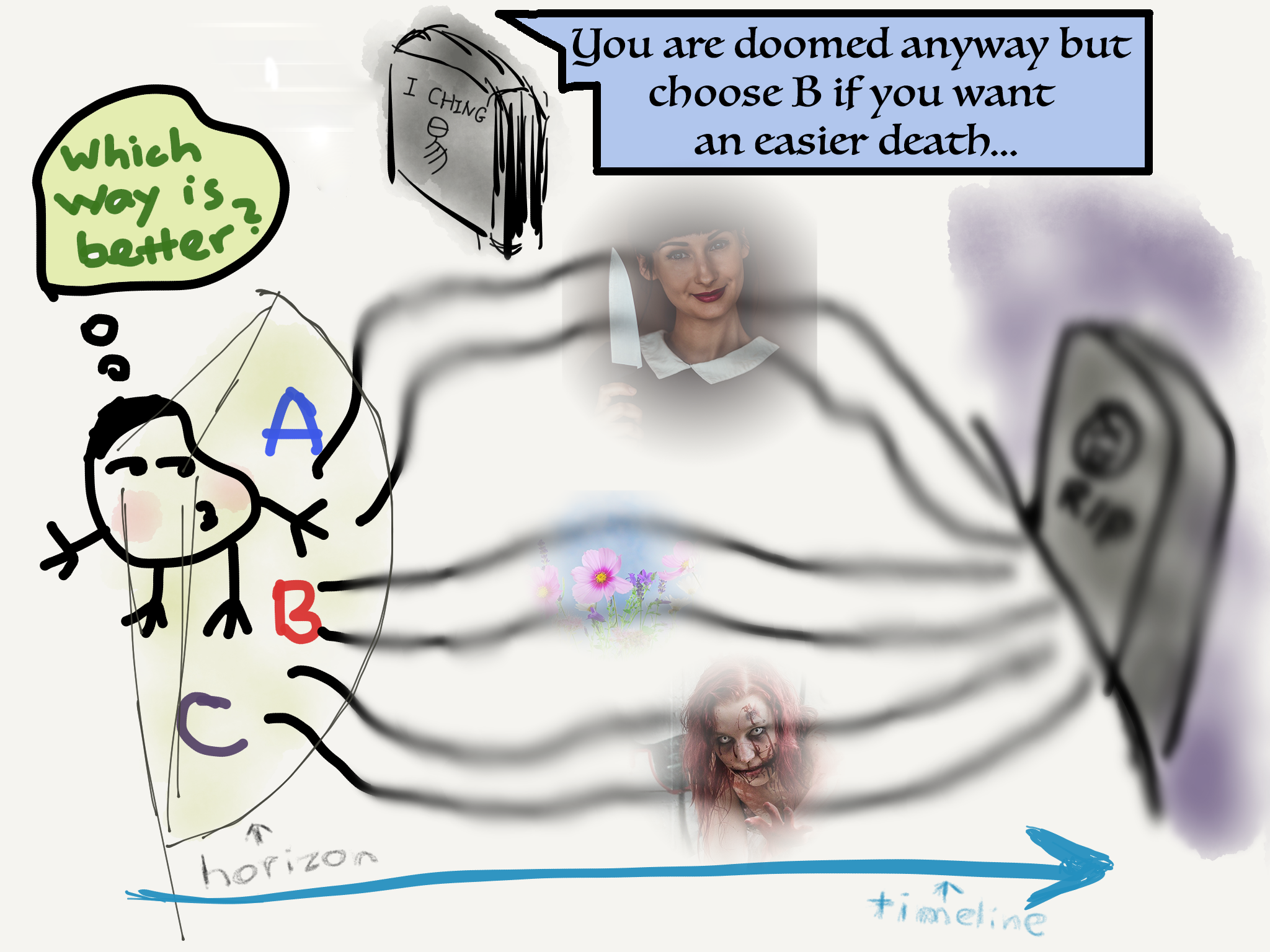

Following Wilhelm’s interpretation rules, which takes into account both the present and the future hexagrams as well as all the changing lines, I guess the two factors above are only crucial in the sense that they are aspects where the questioner’s action can make a (limited) difference but not in the sense that the whole timeline hinges on them. In other words, “fate” only cares about the overall direction of a change but not about the bumps and bruises en route.

Line slots

Just as the upper/lower trigram slots have their predetermined meanings, so each of the six line slots in the hexagram has some fixed interpretation independent of the type of line we insert there. First, the six line slots are “gendered,” with the odd-number slots (from bottom up) being yang (aka masculine) and the even-number slots being yin (aka feminine).

Second, four out of the six line slots of the hexagram come with some configurational good/bad attribution, with the fifth slot from bottom up being the best position in a hexagram. The second slot is also meritorious. The middle (i.e., third and fourth) slots, on the other hand, are deemed dangerous and disquieting. The bottom/top slots don’t have a good/bad attribute for I Ching-internal reasons.

The beginning line is difficult to understand. The top line is easy to understand. The second [line] is usually praised, the fourth is usually warned. The third [line] usually has misfortune, the fifth usually has merit.

(初難知,上易知。二多譽,四多惧。三多凶,五多功。)

— The Great Commentary (Part II), Chapter IX

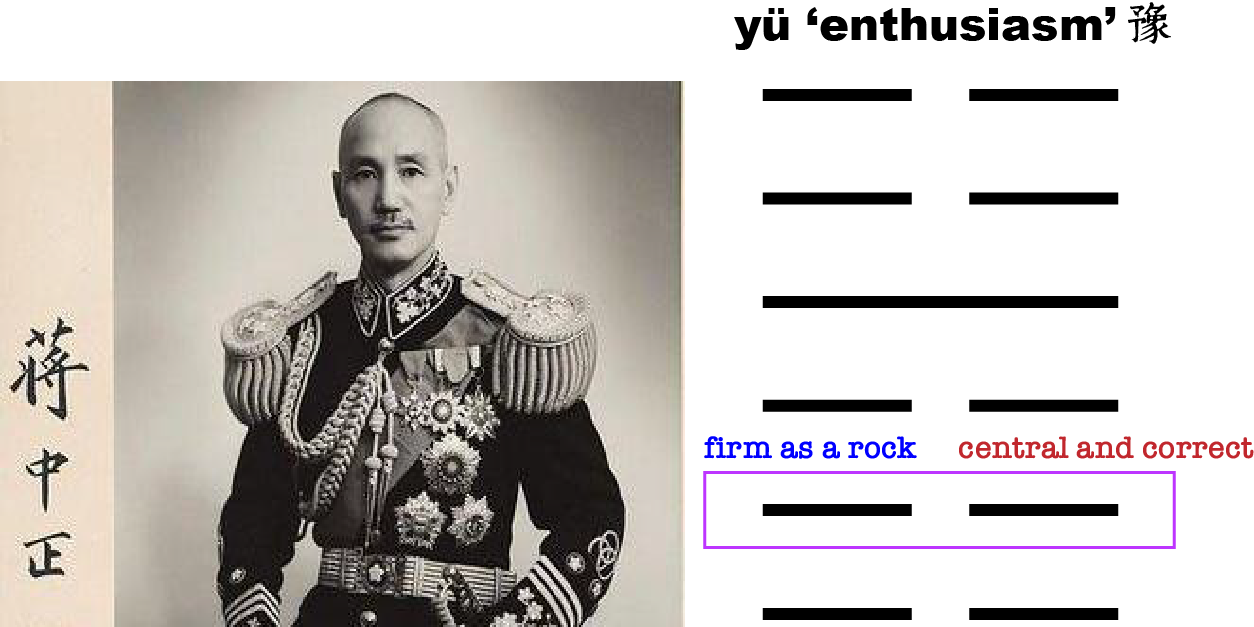

Based on the above two types of line slot meaning, the most auspicious lines in I Ching are those that occupy the fifth or the second slot and agree with those slots in gender; namely, a yang line at the fifth slot or a yin line at the second slot—and a hexagram with both is just wonderful.👑

Cross-line relationships

In historical commentaries of the I Ching we can often see various cross-line relationships; for example, in the figure above the second and the fifth lines are said to be “central and correct.” Relationships like this are supposed to help readers evaluate how auspicious a hexagram is, though in my opinion they aren’t that important for amateurs because one can get exactly the same information from the line statements. I think cross-line relationships are more of a theoretician’s toy, since they can help explain why certain line statements are written that way.

But anyway, I’m listing a few major cross-line relationships here because they represent a different kind of symbolic operation in the I Ching system—besides stacking one symbol on another, we can also link remote symbols together. So, in a hexagram,

- any number of yin lines below any number of yang lines are said to support (承) the yang lines, which is good;

- any number of yin lines above a single yang line are said to ride (乘) the yang line, which is bad;

- each line and the line two slots away from it (e.g., first and fourth, second and fifth) are said to be in correspondence (應), which is only good when the two lines are opposite in gender;

- whatever is in the fifth/second slot is said to be central (中), because these are the middle slots in the upper/lower trigrams;

- a yang line in the fifth slot or a yin line in the second slot is said to be central and correct (中正) because its gender matches that of its slot—this is a highly auspicious configuration;

- if the fifth line is yang and the second line is yin, then they are simultaneously central, correct, and in correspondence (aka “perfectly central” 大中)—this is a best configuration.

At this point I’m reminded of a historical aside: Former ROC President Chiang Kai-Shek’s name and his courtesy name (Chung-Cheng) are both taken from the I Ching. They both come from the interpretation of the second line in the hexagram ䷏ (yü ‘enthusiasm’ 豫). Kai-Shek (介石) means “firm as a rock” and Chung-Cheng (中正) means “central and correct.”

Firm as a rock. Not a whole day. Perseverance brings good fortune.

(介於石,不終日,貞吉。)

“Not a whole day. Perseverance brings good fortune,” because it is central and correct.

(不終日,貞吉,以中正也。)

— statement and commentary of line 2 in Yü

This line is highly auspicious, though unfortunately the entire hexagram isn’t. Also, Chiang isn’t alone in his enthusiasm for the I Ching; most of those who had ever ruled China in the past two millennia, either completely or partially, had been big fans of the book. Its status in traditional Chinese culture is similar to the status of the Bible in the West. Incidentally, the Chinese name for the Bible is Sheng Ching ‘the Holy Classic’ (聖經).

Summary

The result of an I Ching divination session consists of two parts: a hexagram and some (zero or more) changing lines. The hexagram contains information about the status quo of the question being asked, and the changing lines—together with the new hexagram after the changes have been implemented—contain information about its future development.

Practically, to get the interpretation of a divination result all one needs to do is look up the hexagram in the book and read through its chapter. But there’s more to I Ching interpretation than that. An important question that had puzzled distinguished scholars throughout Chinese history is, Why are the statements for hexagrams written the way they are?

Since the compilation time of the I Ching is way too ancient even for Confucius, most of those who have studied the book in history could only follow its text either semireligiously or with some extra theorization. And here’s where the multiple interpretative levels I’ve introduced in this and the last post become relevant—the various structural components and their meanings have enabled scholars to formulate theories about the original I Ching text, thus giving rise to “more than two and a half millennia’s worth of commentary.”

In sum, the overall meaning of a hexagram can be deduced from the meanings of its constituent trigrams. And when those alone aren’t explanatory enough—they certainly aren’t if one wants to provide explanations for the changing lines’ meanings as well—there are still other tools that can help, such as the “nuclear trigrams,” the “slot meanings,” and the cross-line relationships. Note that none of these extra components is actually mentioned in the original I Ching text. They’re just supplementary postulates made by commentators in their endeavor to answer the boldfaced question above.

The original I Ching text has two major components: a list of complex symbols and a record of their final interpretations. The mapping between the two is simply given, without any explanation of how it had been reached. This state of affairs is reminiscent of that in human language. Each language as a ready-to-use product is essentially also a mapping between complex symbols and their interpretations. And a linguistician’s goal is to figure out the details of the mapping. The only difference is that the symbols in human language are naturally evolved whereas those in the I Ching are human-designed. This kind of makes the I Ching symbolic system an “artificial language”—and probably an earliest one in human history.

In the next two posts I’ll enumerate the similarities between I Ching theorization and linguistic theorization I’ve noticed—that is, theorization about how symbolic forms get their interpretations.

Leave a comment