A while ago I came across a website for a Genetic Literacy Project. The slogan of the Project is “science not ideology,” and its goal is to promote science literacy and aid people in understanding the societal implications of genetic engineering. I’m not a big fan of genetic engineering, especially given recent scandals. What caught my attention was a short article posted on the website by Ross Pomeroy (@SteRoPo)—who runs the RealClearScience website by the way—about a new paper in Nature Scientific Reports on the origin of language (de Boer, Thompson, Ravignani & Boeckx 2020). The paper argues based on evolutionary dynamics grounds that language has more likely evolved step by step rather than via a single genetic mutation.

Our results cast doubt on any suggestion that evolutionary reasoning provides an independent rationale for a single-mutant theory of language.

— de Boer et al. (2020)

By “a single-mutant theory” the authors mean the theory of Noam Chomsky, or “the Chomskyan evolutionary conjecture.”

The Chomskyan evolutionary conjecture

This conjecture is based on the assumption that what distinguishes human language from, say, animal communication most fundamentally is hierarchical syntactic structure; that is, the underlying grammatical structures of human language sentences are more about category embedding (often represented by brackets) than about string concatenation. Thus, when a syntactician sees a sentence like “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” what he sees is (1a) instead of (1b).

(1) a. [ [ [ adj ] [ [ adj ] [ n ] ] ] [ [ v ] [ adv ] ] ]

b. "Colorless" + " " + "green" + ... + "furiously" + "."

The essence of hierarchical syntactic structure, according to Chomsky, is a basic combinatorial operation called merge, which creates a set out of two elements.

(2) merge(a, b) => {a, b}

Hierarchical structures are built by iterated application of merge.

(3) merge({a, b}, c) => {{a, b}, c}

👉 or [ [ [ a ] [ b ] ] [ c ] ] in bracketing format

The bracketing format can be further converted to tree format (a type of graph), with each pair of brackets corresponding to a vertex and each instance of the immediate dominance (i.e., set membership) relation corresponding to an edge.

(4)

A basic tenet of Chomsky’s syntactic theory is: however complex a natural language sentence is, it ultimately always boils down to this simple operation “merge.” This extremely simple way to define human language syntax “greatly eases the explanatory burden for evolutionary analysis” (Bolhuis, Tattersall, Chomsky & Berwick 2014), because once the human mind is equipped with merge, it is syntax-ready.

Evolutionary analysis can thus be focused on this quite narrowly defined phenotypic property, merge itself, as the chief bridge between the ancestral and modern states for language.

— Bolhuis et al. (2014)

As to how merge came about in the first place, Chomsky’s position is that it is not a result of the kind of slow, incremental process commonly associated with evolution but rather a recent and rapid emergence; in other words, it is a mutation. For more detail about this conjecture I recommend the recent MIT monograph coauthored by Berwick and Chomsky entitled Why Only Us?

Alternative voices

Being a linguistics student means I’ve had the chance of hearing/reading expert opinions on the origin of language multiple times. Indeed, Cambridge is a nice and tolerant place for open discussions on huge and controversial topics like this one. Sometimes students are too shy to utter their opinions, but the scent of interdisciplinary curiosity is clearly in the air.

I still remember attending a Philological Society talk on the emergence of syntax in my first year of PhD and going to an Evolution of Language reading group in my second year. I got more spiritual galvanization (like “Wow, this is a cool area!”) than academic progress from both events—mainly due to my lack of previous knowledge—but they did help keep me thinking about language from a biological/evolutionary perspective from time to time throughout my stay at Cambridge.

I’ve also noticed an origin of language section on the website of the Darwin Correspondence Project (a Cambridge research team), though for some reason linguistics isn’t listed as a currently-engaging discipline there…👀

Debates about the origin of language are still ongoing. … Such questions, addressed in a variety of scientific disciplines, such as neurology, paleoanthropology, and animal psychology, build upon the work of Darwin and his contemporaries, while taking that work in new directions.

— Darwin Correspondence Project

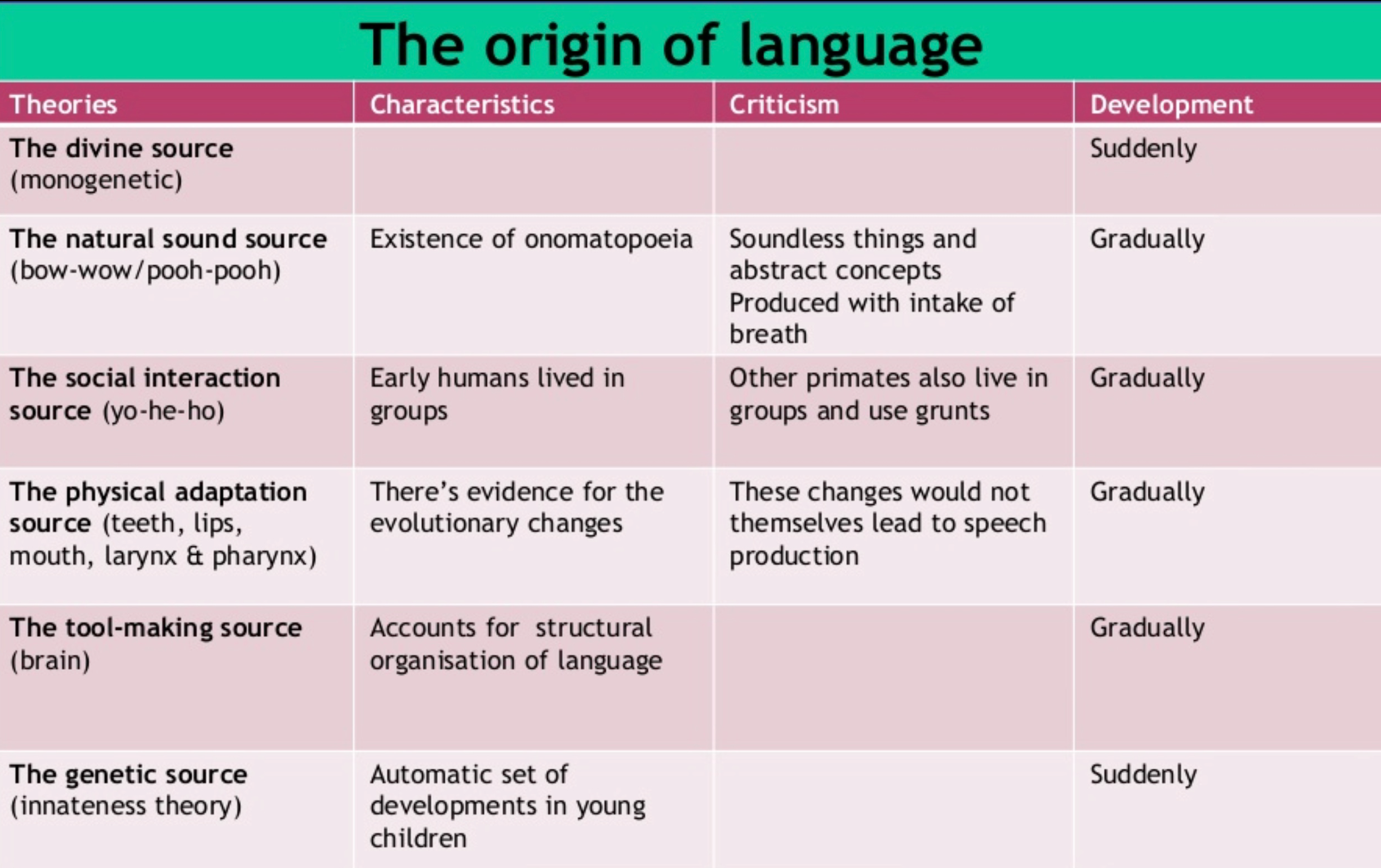

But anyway, the wide attention the issue of language origin has drawn to itself means that the Chomskyan conjecture can’t be the only voice out there—in fact it’s not even the mainstream view. According to Wikipedia “a majority of linguistic scholars as of 2018 hold continuity-based theories”; that is, pro-gradual-evolution (or “gradualist”) theories. The following slide from the Institute of Southern Punjab Multan presents an interesting picture.

Out of the six postulated sources of human language listed in the slide, only two endorse a sudden-development view—the divine source (as in the Bible) and the genetic source (as in Chomsky’s conjecture)—while all the rest are gradualist. Granted, we can’t take an ayes-have-it attitude towards scientific debates (“truth always rests with the minority” as Søren Kierkegaard once said), but suddenists do need to come up with more solid evidence than faith- or conjecture-based argumentation in order to win the wider audience’s hearts and to defend themselves against incessant criticisms, not all of which are unreasonable.

Pinker & Bloom in Behavioral and Brain Sciences (1990):

If a current theory of language is truly incompatible with the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution, one could hardly blame someone for concluding that it is not the theory of evolution that must be questioned, but the theory of language.

ℹ️ Pinker and Bloom argue for a natural selection–based (i.e., gradualist) account of language origin despite their sympathies with Chomsky’s generative grammar.

Ben James on The Atlantic (2018):

Chomsky’s position is such a brazen refutation of known evolutionary processes that Kolodny, Stout, and many of their colleagues aren’t sure how to engage with it. Stout claims that Berwick’s refutation of his research misses the mark entirely. Ultimately … he expects the positions of Berwick, Chomsky and other formalist linguists to find a sort of synthesis with his own views on language, but he doesn’t see agreement occurring anytime soon.

ℹ️ Stout endorses the tool-making or more exactly “technological pedagogy” hypothesis and Kolodny further puts forward a “hijacking”- or exaptation-based—though still gradualist—theory of language origin.

But coming up with solid evidence is difficult. As Ray Jackendoff writes on the Linguistic Society of America website:

The basic difficulty with studying the evolution of language is that the evidence is so sparse. Spoken languages don’t leave fossils, and fossil skulls only tell us the overall shape and size of hominid brains, not what the brains could do.

Without hard evidence, though, the study of language origin is still a game of speculation at the end of the day—not substantially superior to what it was one and a half centuries ago, when speculations got so whimsical that the Linguistic Society of Paris (SLP) decided to ban discussions on the topic altogether.

La Société n’admet aucune communication concernant, soit l’origine du langage soit la création d’une langue universelle. (The Society does not accept any communication concerning either the origin of language or the creation of a universal language.)

— ART. 2, Status de 1866, SLP

See this, this, and this page for some imaginative theories as well as this page for some mythical ones (my personal favorite is the Wurruri story🧟♀️). And also don’t forget the once ambitious mission of finding the mother tongue of our species (such as Nostratic)! Not sure if that quest is still on but sometimes I find the idea cool.

For the remaining content of this article see my next post “Where is language from? (Part 2)”.

Leave a comment