I like writing about Classical Chinese, and I’m keen on formal languages too. So, every time I see the two concepts show up together, I know I have to write something to mark the moment. In this post, I recount two recent experiences with such a moment.

A context-free grammar for Classical Chinese

The first experience happened when I was routinely surfing the Internet a few weeks ago. While doing so, I came across a talk with the title “The Programming Language Called Classical Chinese,” and I was like “Wow, that sounds so cool!” So I clicked in and watched it with my favorite snack.

As it turned out, however, the content of the talk had basically nothing to do with its title. There was probably some underlying connection, but that was a little too subtle to grasp and also only mentioned in passing—in the statement below

Classical Chinese grammar has approximately the order of formal simplicity of a programming language, rather than that of a natural language.

This was the talk’s main claim, which is academically debatable. But I won’t go in that direction, as I did enjoy the talk once I understood its true purpose, which was not to use Classical Chinese as a programming language but to design a context-free grammar that could help parse existing Classical Chinese texts.

That sounds potentially very useful, and it’s much less ambitious than what’s implied by the title too. First, since the context-free grammar is just a helper instead of an full-fledged parser, it could in principle abstract away from many linguistic details. Second, since it’s only meant for parsing, it needn’t be worried about the usual bane of grammatical theories—overgeneration (i.e., the prediction that some ungrammatical string is valid in the target language).

The context-free grammar given in the talk is highly simple yet highly powerful. In fact, it only has two parts of speech and three rewrite rules. The following definitions are taken from the (long!) paper the talk is based on. By the way, the paper not only has a much less “click-bait-y” title (“Wenyan Syntax as Context-Free Formal Grammar”) but also contains a (sub)section that actually compares the proposed grammar to programming languages.👍

(Wenyan 文言 is the Chinese term for Classical Chinese.)

Categories: Noun, Verb

Rules:

1. ⟨S⟩ ::= ⟨VP⟩ | ⟨NP⟩

2. ⟨NP⟩ ::= ⟨NP1⟩ ⟨NP2⟩ | ⟨NP⟩ ⟨VP⟩ | (⟨NP1⟩)-⟨NP2⟩ | (⟨VP⟩)-⟨NP⟩ | ⟨VP⟩ | N

3. ⟨VP⟩ ::= ⟨VP1⟩ ⟨VP2⟩ | ⟨VP⟩ ⟨NP⟩ | (⟨VP1⟩)-⟨VP2⟩ | ⟨NP⟩ ⟨VP⟩ | (⟨NP⟩)-⟨VP⟩ | ⟨NP⟩ | V

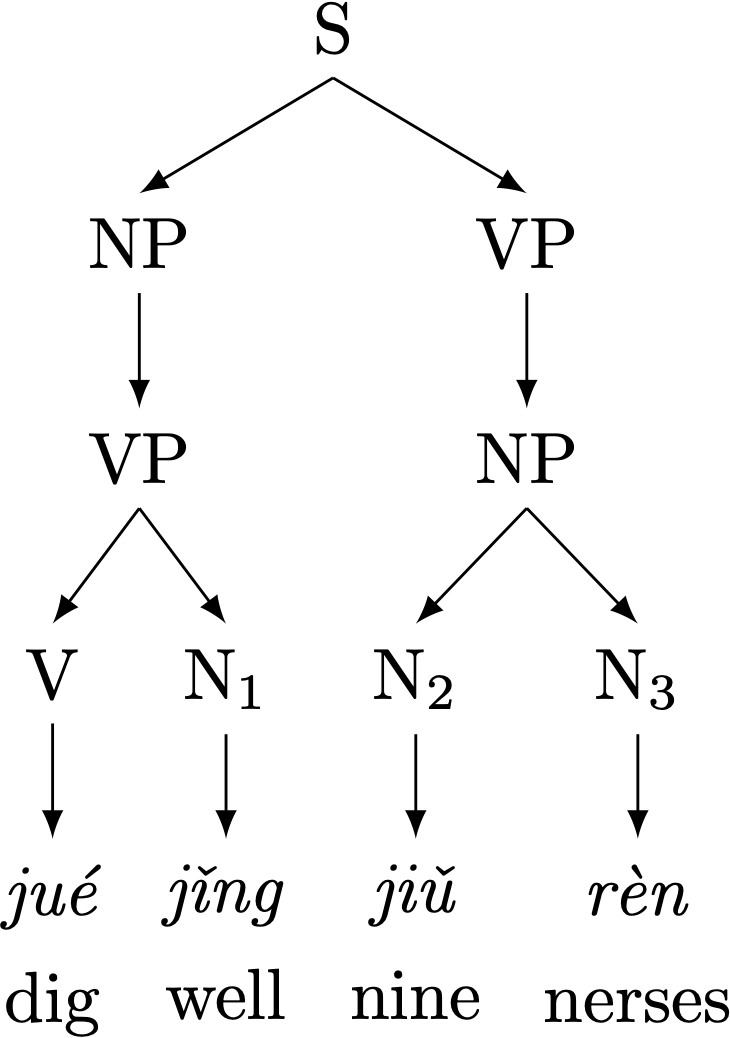

To illustrate, let’s see a concrete example from the paper (adapted from p.38), where the expression 掘井九軔 jué jǐng jiǔ rèn ‘to dig a well nine nerses deep’ (which is simultaneously a VP and an S) is parsed as follows.

According to the talk and the paper, if we abstract away from

- morphophonemics (which Classical Chinese has little anyway),

- the majority of semantically oriented categories (which are syntactically insignificant in Classical Chinese), and

- function words (which mainly serve disambiguating purposes from the angle of parsing),

then all we need is the context-free grammar given above in order to parse any given Classical Chinese sentence.

As mentioned above, I’m somewhat skeptical about this as a fellow linguist. But I can’t deny that the 2×3 grammar indeed does what it promises to do—and it can’t be evaluated or criticized for what it doesn’t. As the speaker says in his paper (p.12):

This is a model for analyzing premodern Chinese written language. It does not promise to produce correct sentences, and it is not meant [to] apply to oral language.

A Classical Chinese-based programming language

Compared to the talk I randomly discovered, the other Classical Chinese-Formal Language combo that I recently experienced seems more readily evaluable. It is a Classical Chinese-based programming language called Wenyan.

Wenyan: a senior’s pastime

I’ve blogged about programming language vs. natural language before, and if you’ve read that post you probably still remember that there’s quite a gap between these two language types. So, when I first learned about this thingy I was a bit like

However, after reading about it for a while, I realized that it was actually kind of cool—well, both cool and smart!🕺 The language was created in 2019 by a CS student Lingdong Huang (黃令東) during his last month at Carnegie Mellon University, who apparently wasn’t suffering from senioritis.👨💻 Below is the Hello World program implemented in Wenyan (source).

吾有一數曰三名之曰「甲」

為是「甲」遍

吾有一言曰「「問天地好在。」」書之

云云

We can roughly translate this into English as

I have a number. It says 3. I name it 甲.

Do this 甲 times.

I have a sentence. It says "Hello world!" Write it.

Stuff like that.

The Wenyan programming language is (originally) built on JavaScript, so the above code is underlyingly

var n = 3;

for (var i = 0; i < n; i++) {

console.log("問天地好在。");

}

and its output is (as expected)

問天地好在。

問天地好在。

問天地好在。

(P.S. It’s interesting that Huang has translated “Hello world!” into Classical Chinese as 問天地好在, which isn’t an inherited saying but roughly means “I ask about the well-being of Heaven and Earth.”)

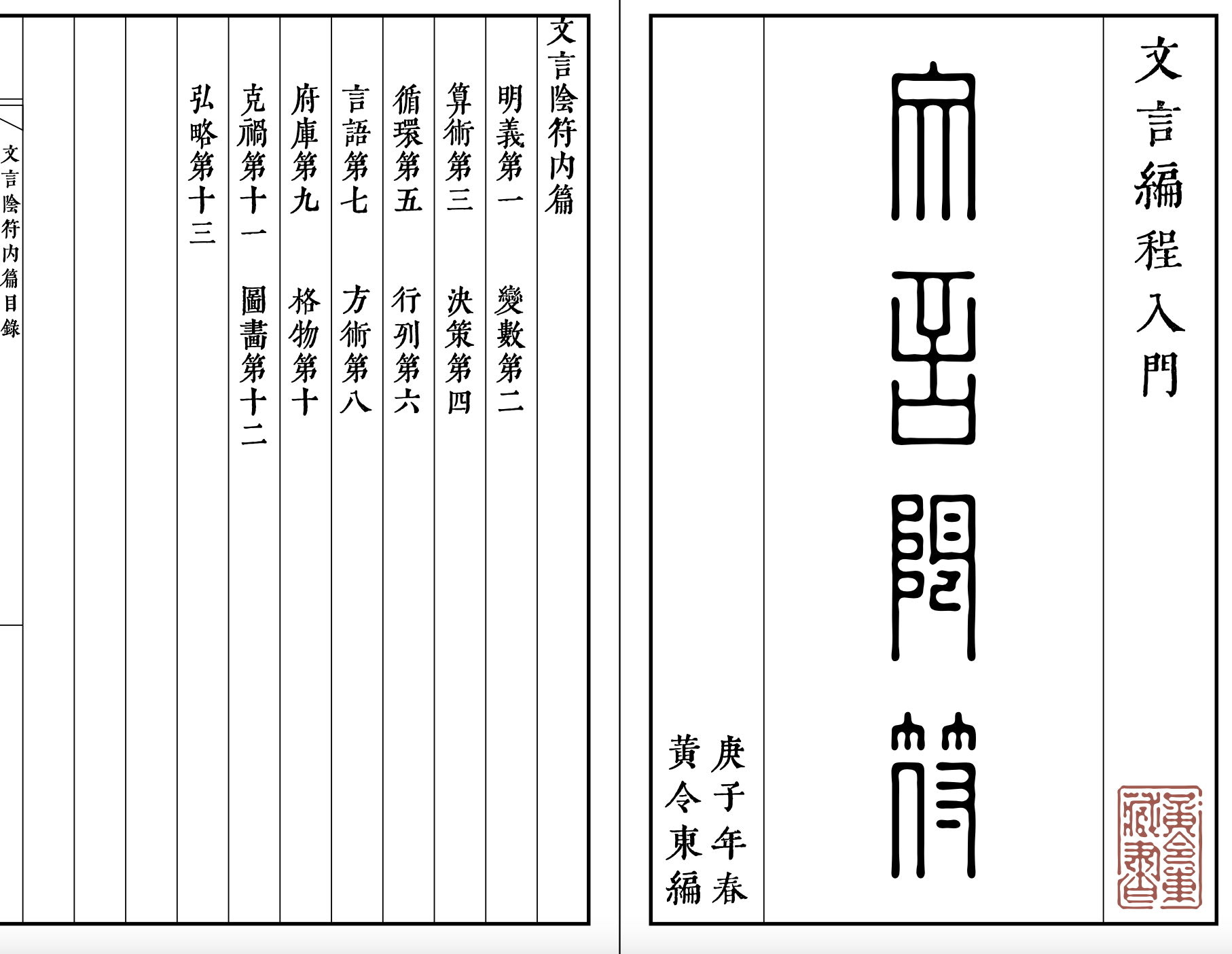

Once it was posted on GitHub, this refreshingly intriguing toy language quickly attracted public attention, mainly from other Chinese students and programmers. Subsequently, a community of contributors was automatically formed (see this and this page for some interesting code snippets). There’s also been some blogposts (e.g., this, this, this, and this) and forum threads (e.g., this and this) on it. Huang himself is quite enthusiastic too. In 2020, he wrote a 79-page-long, beautifully formatted handbook for Wenyan entirely in Classical Chinese!

A unique esolang

Esoteric programming languages (aka esolangs) are pretty common nowadays, from the more famous Shakespeare and Brainfuck to the lesser-known Chef and Befunge. There’s even one written for orangutans and one written in Klingon…🤣 Compared to its predecessors, Wenyan looks unique in that it’s designed entirely in Classical Chinese, with all programming elements being written in traditional Chinese characters. For instance,

- variable names: 甲 jiǎ, 乙 yǐ, 丙 bǐng, etc. (the Heavenly Stems)

- type names:

- 爻 yáo (

boolean, literally a line from I Ching—check out my post on I Ching divination by the way🙂) - 列 liè (

list, literally “column”) - 術 shù (

function, literally “technique”) - etc.

- 爻 yáo (

- booleans: 陰 yīn (negative/false), 陽 yáng (positive/true)

- etc.

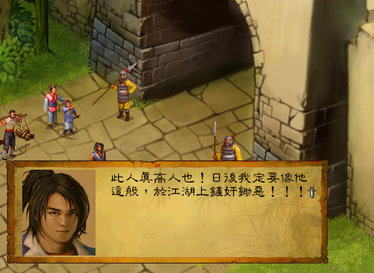

In fact, the style of Wenyan is so purposefully ancient that I have the impression that the language has been created with a hypothetical ancient programmer in mind. Maybe that’s why Huang has painstakingly chosen quasi counterparts from ancient Chinese culture (many from Taoism) to represent modern programming concepts. Apart from the above-listed, the following ones are also pretty brilliant:

- For module importing: 吾嘗觀 … 之書方悟 … 之義

“Once I saw the book of module. After that I understood the meaning of function.”

JS:var {<function>} = require('<module>'); - For function definition: 吾有一術名之曰…欲行是術必先得…乃行是術曰…乃得…是謂…之術也

“I have a technique. I call it function. If you want to practice this technique. You must first get parameters. Then you practice this technique, which says definition. Then you get result. This is what is called the technique of function.”

JS:function <function name>(<parameters>) { <function definition>; } - For comments: 批曰/注曰/疏曰…

“I comment saying comment.”

JS:/* <comment> */

The above module-importing and function-defining statements sound really like lines from Wuxia- or “martial hero”-themed RPG games, which I used to play in junior high. As for the comment statement, it sounds like the programmer is annotating some Confucian or Taoist classic.

Apparently, Wenyan is not the only Classical Chinese-based programming language out there, nor is it the first one ever. A Taiwanese programmer had already invented a Classical Chinese version of Perl back in 2009, and just two months ago (in July 2021) another GitHub user posted a toy project Jiuzhang based on Cirru. But so far Wenyan seems to be the most promising one of its kind, for it’s under regular maintenance and equipped with a series of professional-looking pluses, including an IDE, a handbook, and a growing number of mystical-sounding packages.

A beautiful handbook

I’d like to say a few more words about the above-mentioned handbook. It strikes me not only as a programming tutorial but also as a nicely composed literary work. It employs a broad range of rhetorical devices and historical-cultural references, which makes the tedious algorithms read like philosophical prose.

A rhetorical device Huang uses a lot is xīng (興), which is highly common in Classical Chinese literature since The Classic of Poetry (詩經) and roughly means “speaking first of something else to lead up to the main theme” (Wiktionary). Huang tends to use xīng together with parallelism. The example below is from Chapter 4 of the handbook (p.21), where conditionals are first introduced:

決策者。萬智之始。何耶。曰察而後動。魚之相吞。必先度彼之大小。犬之嚙人。必先觀主之喜惡。此禽獸之決策也。雨而蓑。寒而衣。價善乃沽。人善乃欺。匹夫之決策也。陟罰臧否。伐謀伐交。卿相之決策也。其所以智於向者。唯決策有難易之別耳。故程式之能於決策者。智比於人。不能者。止一算盤耳。

“Decision making is the beginning of all intelligence. What is it then? It is called observing and then acting. When a fish swallows another fish, it must first measure its size. When a dog bites a person, it must first observe its owner’s attitude. These are animals’ decisions. Putting on a straw rain cape if it rains, putting on some clothes if it is cold, trading if the price is good, and deceiving others if they are kind, these are ordinary people’s decisions. Rewarding the good and punishing the bad, fighting with strategies and fighting with diplomacy, these are officials’ decisions. The reason why these people are wiser than the aforementioned is just because different decisions have different difficulty levels. Thus, if a program is capable of making decisions, then its intelligence can be compared to that of humans; if not, it is no more than an abacus.”

Notice how Huang describes an array of decision-making scenarios in parallel before he finally touches on the theme of the chapter. It’s obvious that he has read extensively in Classical Chinese, as the paragraph reads pretty natural (maybe except for 向者 and 能於, which sound a bit awkward to me). Therefore, reading through the handbook is an enjoyable experience even if one doesn’t intend to learn the programming it teaches.

Some wee complaints

As a linguist, my biggest impression of Wenyan is that it has a highly personalized language style (which esolang doesn’t lol?). And while it has tons of merits, I can’t say that I absolutely adore everything about it. For instance, it generally sounds a bit “egocentric” to me. Variable assignment is done by the pattern I have a <type>. It says <value>. I call it <variable>. While the first two sentences can be reduced as There is a <type> saying <value>, there’s no such paraphrase for the third sentence. Similarly, the above-mentioned module-importing statement Once I saw the book of <module>. After that I understood the meaning of <function>. sounds equally “self-centered.”

On the other hand, Wenyan is also explicitly (or even “loudly”) imperative, as its commands tend to be very direct in terms of sentence structure. For instance, its printing/logging command is 書之 ‘write it’, its infinite loop command is 恆爲是 ‘always do this’, and its function calls are all of the pattern 施…於… ‘cast … onto …’, which sounds a bit like casting a spell…😝 To abuse a linguistics cliché, Wenyan wears imperativeness on its sleeves.

Besides, Huang’s choice of function word is not always to my taste either, especially when a particle is mechanically adopted for scoping/pattern-matching purposes, because that’s when I get reminded that what I’m reading is still code for machines rather than prose for truly intelligent beings and that we still have to dumb things down at the cost of syntactic flexibility. One particular case that makes me think so is the excessive use of 曰 yuē (literally “say”) for value declaration and variable assignment, which becomes rather verbose when there are multiple variables, as in

(1) 吾有三數曰三曰九曰二十七名之曰甲曰乙曰丙

“I have 3 numbers: 曰3 曰9 曰27. I call them 曰jiǎ 曰yǐ 曰bǐng.”

where 曰 is repeated six times when, in natural Classical Chinese, just two would do:

(2) 吾有三數曰三九二十七名之曰甲乙丙

“I have 3 numbers: 曰3, 9, 27. I call them 曰jiǎ, yǐ, bǐng.”

(I have left 曰 as such because there’s no good way to translate it into English without losing the programming pattern.)

Another case that I think breaks the otherwise fairly natural Classical Chinese text flow is the obligatory use of 也 or 云云 to mark the end of a code block, such as a loop or a conditional. These words have obviously lost their original meanings in this usage and merely serve punctuational purposes. Below is a typical example.

恆爲是

若「甲」等於「乙」者

乃止

或若「甲」大於「乙」者

減「甲」以「乙」昔之「甲」者今其是矣

若非

減「乙」以「甲」昔之「乙」者今其是矣

也

云云

夫「甲」書之

This roughly translates into pseudocode as

Always do this.

if 甲 = 乙:

stop;

else if 甲 > 乙:

甲 = 甲 - 乙;

else:

乙 = 乙 - 甲;

END IF

END LOOP

Write that 甲.

In real code the END IF and END LOOP above would both be replaced by }, but in Wenyan they are written as 也 and 云云, despite the fact that these are clause-level particles in Classical Chinese that must appear in particular syntactic contexts, such as

(3) [NP 舜] [S [NP 冀州之人]也]

Shùn, jìzhōu zhī rén yě.

“Shun is a person from Jizhou.”

(也 makes a proposition out of a noun phrase)

(4) [NP 上] [VP 曰[S 吾欲云云]]

Shàng yuē wú yù yúnyún.

“The Emperor said: I want to blah blah blah.”

(云云 stands for omitted content in direct speech)

Clearly, the usage of 也 and 云云 in Wenyan violates Classical Chinese grammar for computer’s sake. While that’s totally understandable, it does make the programming language look a bit less harmonious.🤔

A last (but one) glitch I notice in Wenyan concerns the use of 是 shì. This is the default copula in Mandarin but a demonstrative in Classical Chinese, yet apparently both functions are used by Wenyan (which shouldn’t be the case!). In the above-mentioned loop statement

(5) 爲是「甲」遍

wéi shì jiǎ biàn

“do this jiǎ times”

是 is clearly used as a demonstrative “this.” However, in the variable reassignment statement

(6) 昔之「乙」者今「甲」是矣

xī zhī yǐ zhě jīn jiǎ shì yǐ

“what used to be yǐ has now become jiǎ”

是 is clearly not used as a demonstrative. Instead, it feels more like a copula or at least an affirmative particle. In this context, a more suitable expression is probably

(7) 昔之「乙」者今爲「甲」矣

(translation as above)

for 爲 wéi ‘be’ is the real copula in Classical Chinese, at least according to Pulleyblank. Or alternatively, we could forget about the perfect aspect and simply say

(8) 昔之「乙」者今「甲」也

xī zhī yǐ zhě jīn jiǎ yě

“what used to be yǐ is now jiǎ”

which serves the reassignment purpose equally well.😃

(P.S. I also notice an excessive use of 其 qí as an anaphoric pronoun, which is not always adequate case-wise, but I’ll stop here for fearing of appearing too nitpicky…😝)

Final words

In spite of my nitpicking, I surely am a fan of Wenyan. And I quite look forward to its future developments too, especially those that could turn it into an all-around programming language that could be put in real-world application. Maybe one day there will even be an entire app (or OS!) written in it. How cool would that be!🙃

Leave a comment