In Part 5 I finished reviewing the pronunciation and character parts of von der Gabelentz’s textbook. In this final part I’ll continue to review its syntax part. Then I’ll wrap up this long blogpost with a short conclusion. Thanks for reading till here! 😊

4. Chinesische Grammatik (continued)

Syntax part

Rating: ★★★★☆

I’ve already made some comments on the syntax part of von der Gabelentz’s textbook in Part 5 when I criticized its overall structure. While that’s indeed a major dissatisfaction I have with the book, here I’d rather leave it aside and only focus on the internal content of the two syntax parts so that I can say something nice about them 😁—because I actually quite like how the author presents various grammatical points.

Linguistic orientation

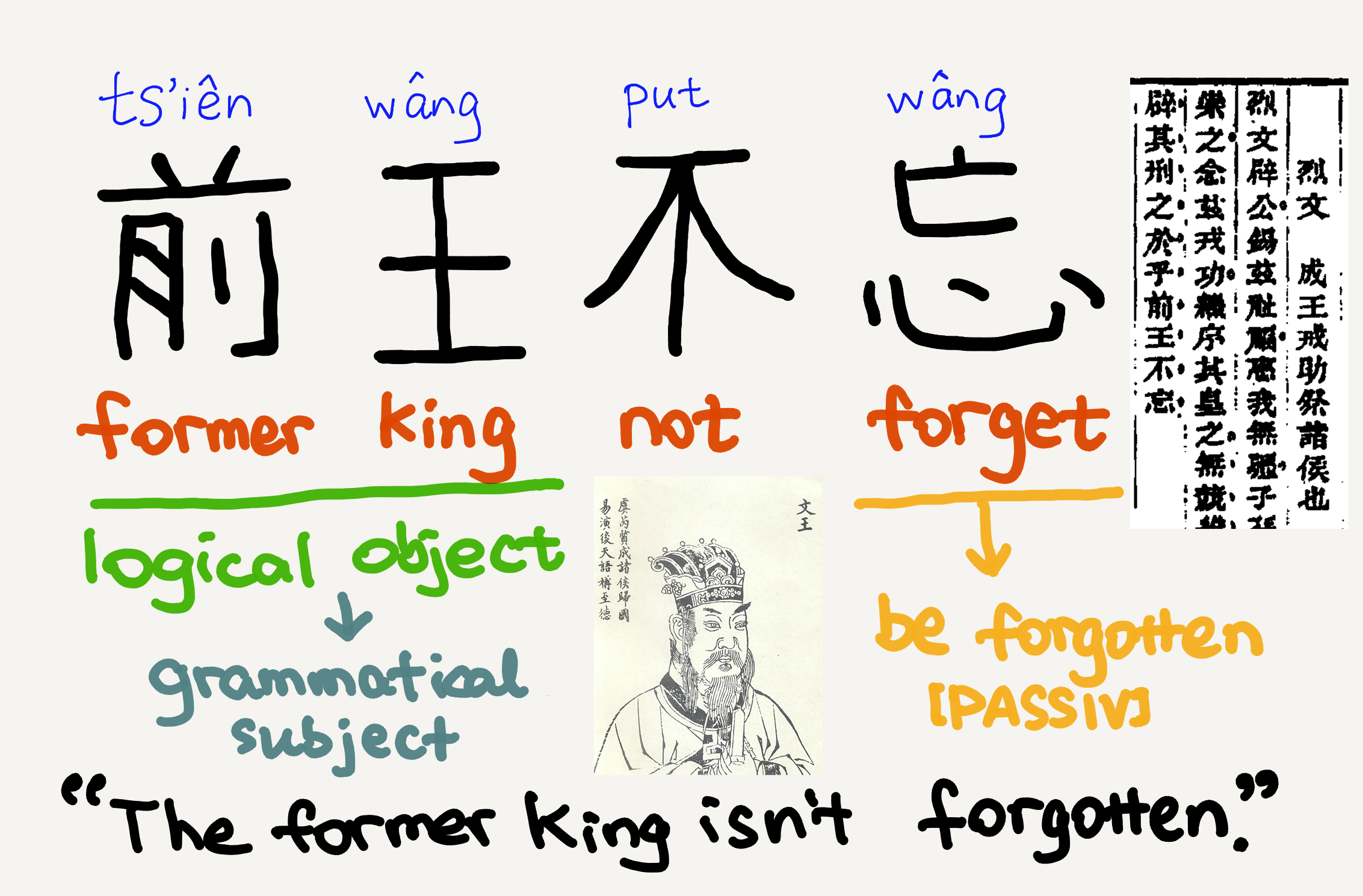

A first aspect of von der Gabelentz’s book that I’ve personally enjoyed, as aforementioned, is its linguistically oriented nature. This is especially evident in the syntax part of the book, for even though the author doesn’t use contemporary terminology, his mindset is very similar to that of a modern-day linguist. For example, when teaching the passive voice, he explicitly distinguishes grammatical and logical arguments, which is also a key distinction in modern linguistics (in the theory of the syntax-semantics interface):

Zuweilen tritt das logische Object als grammatisches Subject vor das Verbum. Dieses wird dann Passivum und nimmt in der Regel die letzte Stelle im Satze ein. (Chinesische, p.138)

“Occasionally the logical object steps to the front of the verb as the grammatical subject. The verb then becomes passive and as a rule occupies the last position in the sentence.”

Similarly, when teaching the sentence-final particles the author makes a spot-on remark that these particles actually function at a different level of the grammar. What he terms the “psychological” level is just the discourse level in modern terminology.

Alle hier zu behandelnden Hülfswörter sind ihrer Wirkung nach modal, und zwar zunächst nicht logisch, sondern psychologisch, das heisst: sie erklären in erster Reihe … das Verhältniss des Redenden zur Rede, seine Stimmung oder Absicht dabei…. Nur mittelbar, in zweiter Reihe, können sich daraus logische Modalitäten, z. B. Gewissheit, Möglichkeit, Wahrscheinlichkeit, ergeben. (Chinesische, p.315)

“All auxiliaries to be handled here are modal in terms of their effects, and more specifically, they are psychological rather than logical. That is, what they primarily express are the relationship of the speaker to the speech [and] his mood or intention with it…. Only indirectly and secondarily can logical modalities like certainty, possibility [and] probability arise therefrom.”

Given surprises like the above, von der Gabelentz’s book can be a really pleasant read for a linguist, even for someone whose aim is not to acquire the Chinese language but just to see how it works.

Lexicocentric presentation

A second merit of the syntax parts of von der Gabelentz’s book is the way it presents the grammatical points. Unlike the previous three authors, who had more or less all adopted the Indo-European grammatical system as the underlying framework and simply fit Chinese grammar into it, von der Gabelentz hadn’t set up any overarching framework at all.

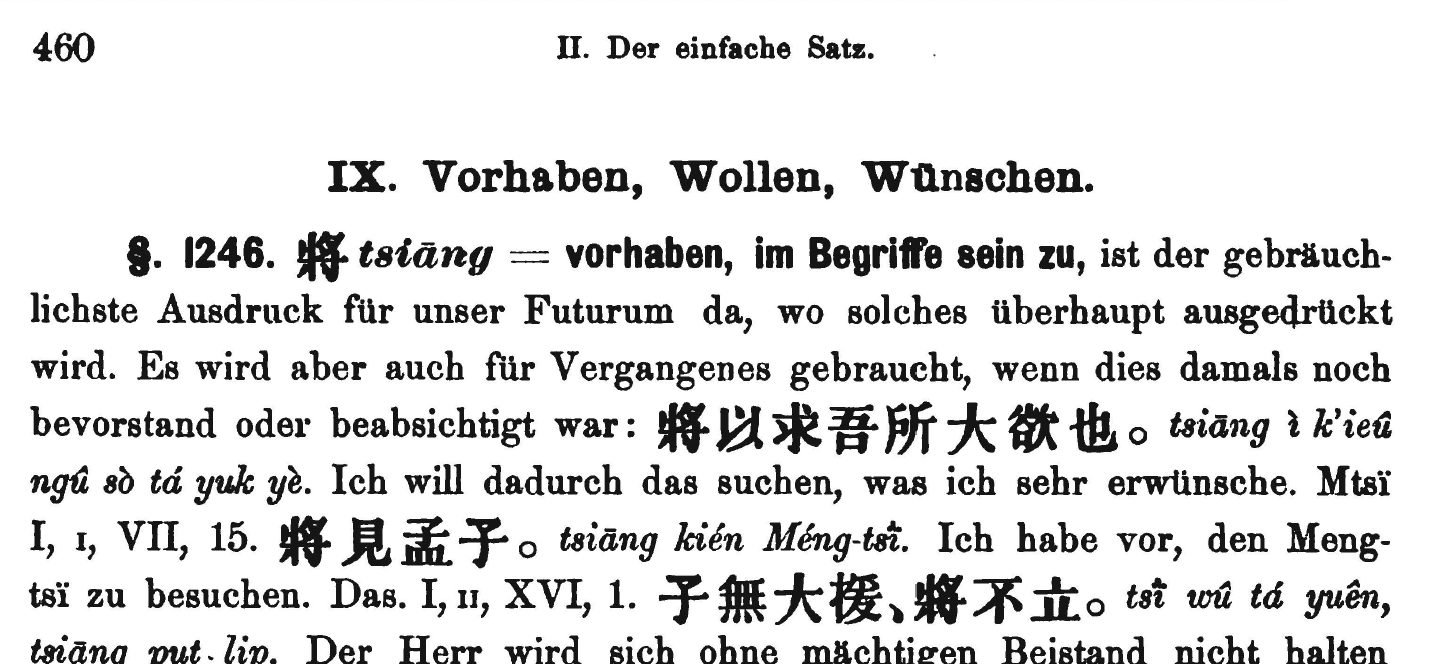

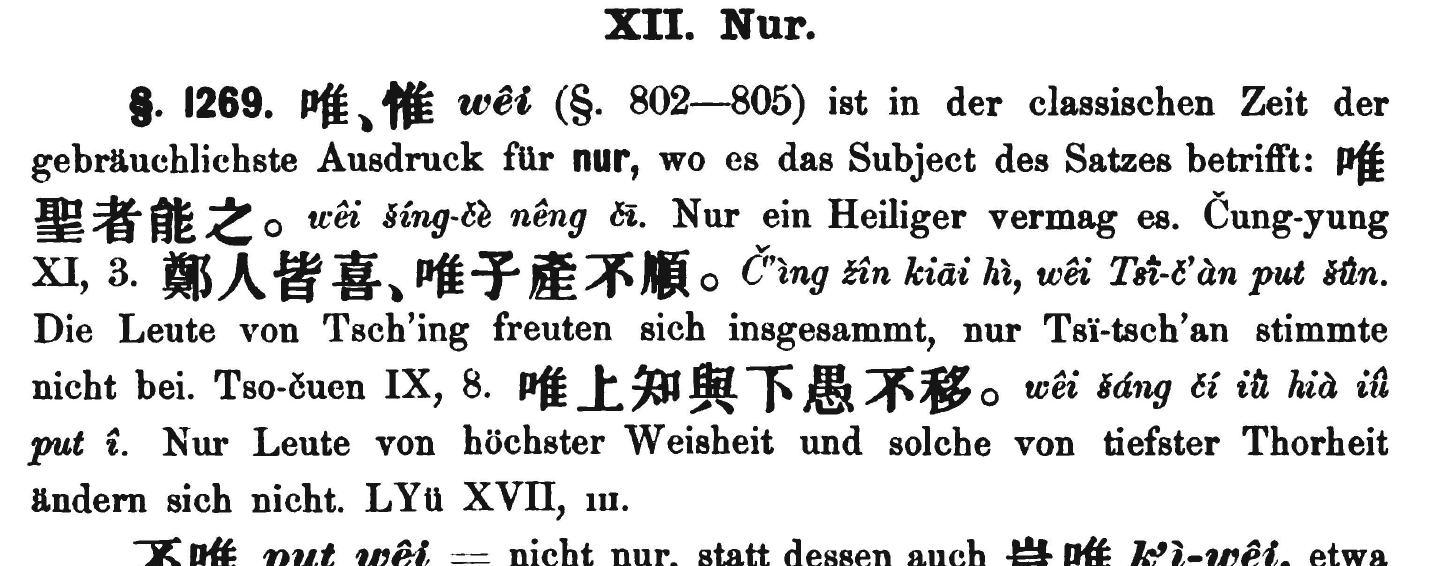

Thus, there’s no section in the book entitled “the future tense” or “the subjunctive mood”—because Chinese doesn’t have those categories formally distinguished—but only a section entitled “planning, wanting, wishing” (Vorhaben, Wollen, Wünschen, p.460), where the author introduces various auxiliaries that express these meanings, including 將 jiang1, 其 qi2, 蓋 gai4, etc.

Actually this way of presentation is seen throughout the syntax parts of the book, not only for grammatical words but also for less grammatical words. For instance, the author teaches many adverbs in the section entitled “only” (Nur, p.465), and even though those adverbs are more or less all synonymous, he manages to explain their differences fairly clearly.

Since the author teaches Chinese vocabulary (especially its functional vocabulary) in such a semantically themed fashion rather than an Indo-European-style paradigmatic fashion, readers get to learn the language in a more natural way almost like a child. That is, one primarily learns how to use each function word, and the syntactic system will build itself along the way.

But of course, this mode of learning is more suitable for Chinese than for Indo-European languages, because functional elements are mostly standalone words in the former but inflectional affixes in the latter. For the latter type of language the paradigmatic approach is still more powerful, precisely because inflection is much less flexible than free-standing words, and so learning it via paradigms is much more efficient than doing so via individual words.

A famous scene from the movie Life of Brian that shows the rigorousness of Latin inflection

Perspective switch

So, by a simple switch of perspective—from a paradigmatic perspective to a lexicocentric one—the author frees Chinese grammar from Western “shackles.” This switch of perspective presumably wasn’t easy in the 19th century, both due to the Eurocentric atmosphere and due to the lack of modern linguistics methodology, so the author indeed had a linguistic mind ahead of his time. 👍

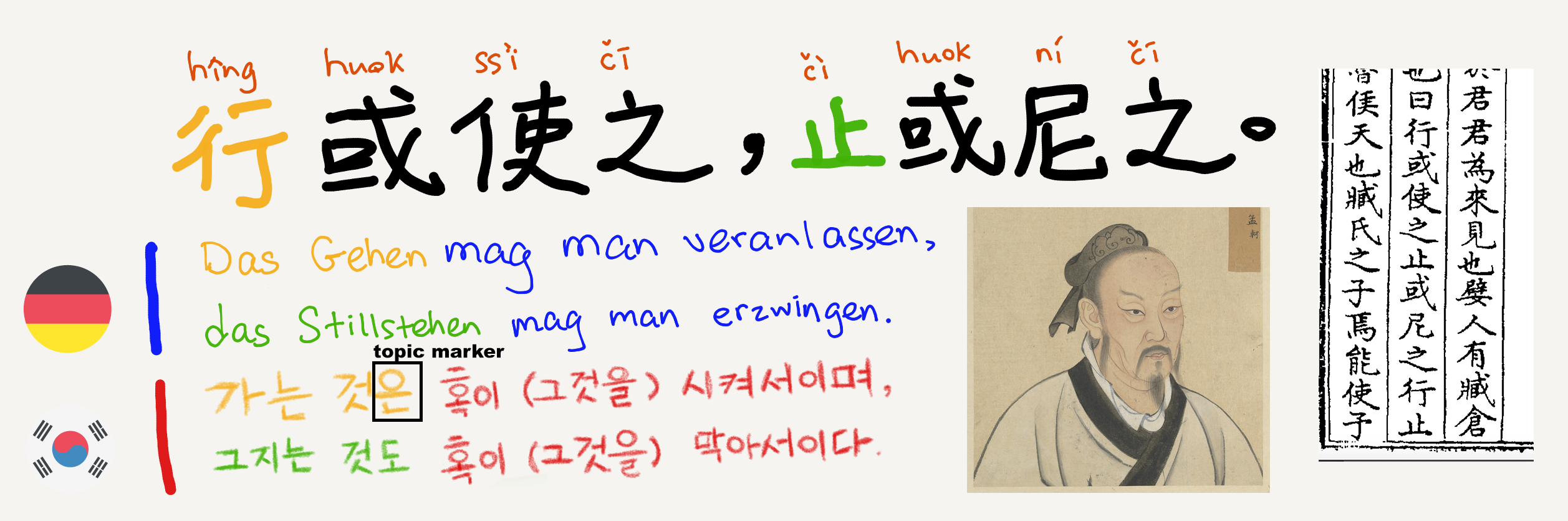

A direct result of the above-mentioned switch of perspective is that some Chinese-specific categories—or more exactly categories not so conspicuous in Western languages—finally get the spotlight they deserve. A good example of this is the author’s separation of the “grammatical subject” and the “psychological subject,” which in modern terminology is just the contrast between the proposition-level subject and a discourse-level “subject.” The latter is often (but not necessarily) a topic-type constituent.

Das psychologische Subject … sei es nun zugleich grammatisches Subject, oder Object, Adverb, Genitiv zu irgend welchem Satztheile oder die Beziehung zweier Satztheile zu einander selbst, hat stets den Satz zu eröffnen. (Chinesische, p.432)

“The psychological subject … be it now at the same time the grammatical subject, or the object, or an adverb, or the genitive to some sentence part, or the relationship between two sentence parts itself, must always starts the sentence.”

For example, in the sentence 行或使之止或尼之 ‘[As to a man’s] going, maybe someone has made him [do so]; [as to a man’s] stopping, maybe someone has prevented him [from going]’, the psychological subjects “going” and “stopping” are the topics of the sentences and can be introduced via an “as to” phrase. Topicalization is evidently more natural and frequent in Chinese and German than in English, and it’s even more explicit in languages like Korean, where there’s a dedicated topic marker (n)eun 은/는.

Succinct explanations

Another manifestation of the author’s sharp linguistic mind lies in his succinct explanations of some highly complicated Classical Chinese-specific syntactic phenomena, such as object fronting (p.145 ff.), 所 suo3 relativization (p.145), and the numerous functions of the particle 之 zhi1 (p.177 ff.). Read the following excerpts for a taste:

Das objective Relativpronomen 所 sò, welchen, welche, welches, sowie das gleichbedeutende alterthümlliche 攸 yeû, wird stets anteponirt. (Chinesische, p.145)

“The objective relative pronoun 所 sò ‘which’, as well as the synonymous archaic 攸 yeû, is always fronted [to the beginning of the relative clause].”

Zwischen das Pronominalobject und das Hauptverbum können Hülfsverben oder Adverbien treten, und dem Hauptverbum kann noch ein zweites Object folgen. (ibid., p.147)

“Auxiliaries or adverbs can step between the [fronted] pronominal object and the main verb, and the main verb can still be followed by a second object.”

Tritt genitivisches 之 čī zwischen Subject und Prädicat eines Satzes – sog. subjectives 之 čī –, so wird dieser Satz in einen Satztheil verwandelt und kann syntaktisch gleich einem Substantivum behandelt werden. (ibid., p.185)

“When the genitive 之 čī steps between the subject and the predicate of a sentence – the so-called subjective 之 čī –, this sentence becomes part of another sentence and can be treated syntactically like a noun.”

Beginner’s version

The author keeps presenting grammatical points in a lexicocentric fashion in the beginner’s version of the textbook. Thus, in the “newer language” part he teaches colloquial Chinese syntax via the particular uses of particular words, but not vice versa. For example, in the section on verbs, he doesn’t directly teach categories like tense and aspect (which in a grammar book for an Indo-European language would surely become section headings) but teaches them through concrete auxiliaries. To name a few,

要 yaó, wünschen, n. futuri.

有 yeù, haben, nach Negationen: n. perfecti.

見 kién (sehen), 受 šeú (empfangen), 吃、喫 k'ik, č'ik (essen), sämmtlich Zeichen des Passivums. (Anfangsgründe, p.97)

要 yaó ‘wish; future tense marker’

有 yeù ‘have; perfective aspect marker after negation’

見 kién ‘see’, 受 šeú ‘receive’, 吃、喫 k'ik, č'ik ‘eat’, all used as passive markers

This way of teaching makes sense because categories like tense, aspect, and voice aren’t really grammaticalized in Chinese—or at least not grammaticalized to the degree of inflection—and the relevant auxiliaries here aren’t really dedicated grammatical markers either. For example, although the three verbs for “see,” “receive,” and “eat” can all be used to express passive meanings, they are preferred in different semantic/pragmatic contexts. Compare:

(1) 古聖賢有遁世不見知的 (Dream of the Red Chamber, Ch. 82)

“Some ancient sages lived in seclusion and were not known.”

(見 is usually used in neutral contexts)

(2) 少時終須喫摑 (Dunhuang Bianwen, Ode to Swallows)

“In a moment you will surely be slapped.”

(喫 is usually used in negative contexts)

Also, in the colloquial part the author doesn’t really teach the entire grammatical system of Early Modern Chinese but merely highlights those aspects that are obviously different from Classical Chinese grammar. As such, the beginner’s version of the textbook is furthermore an excellent reference for linguists who are interested in the diachronic grammatical changes of the Chinese language.

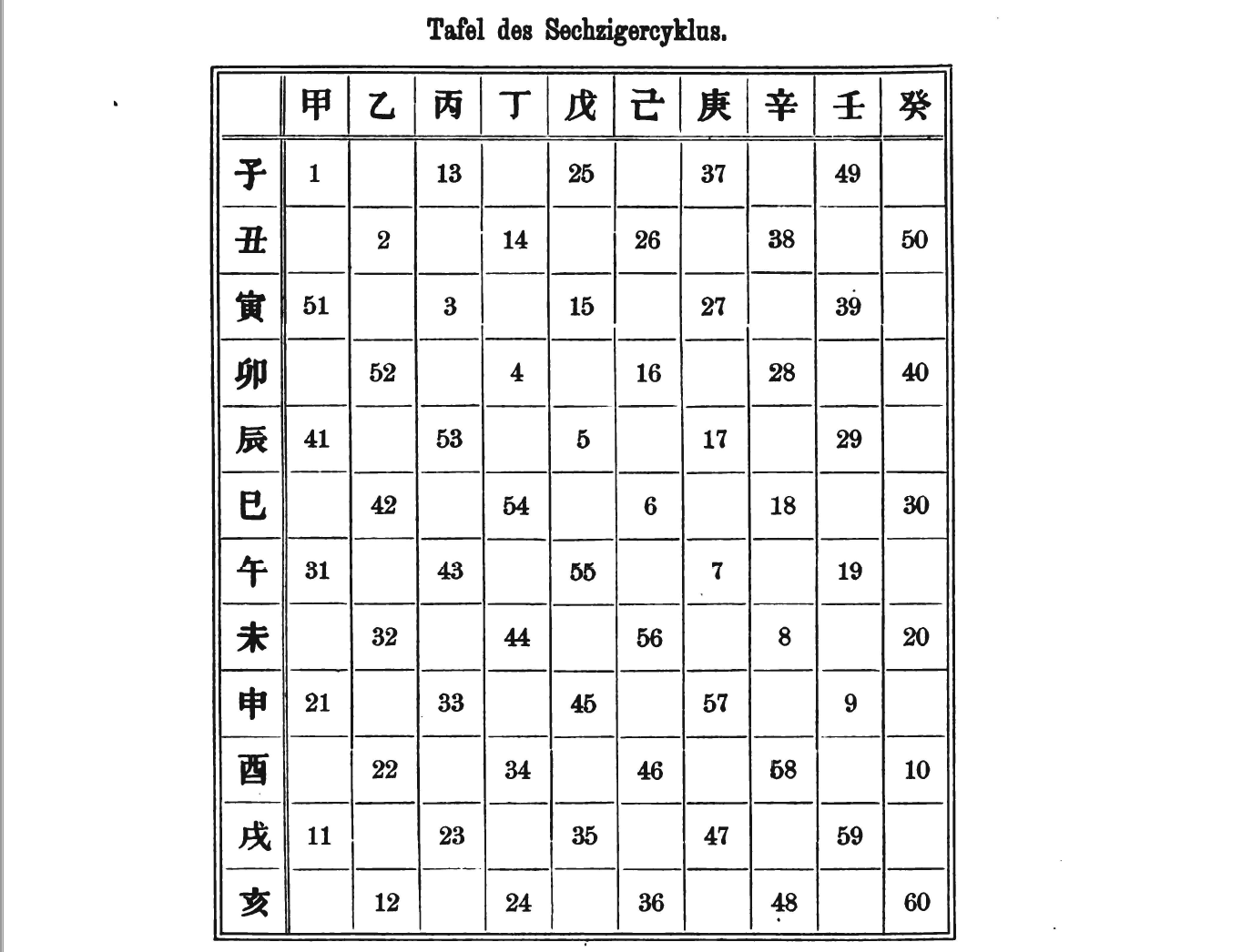

There are still many meritorious places in von der Gabelentz’s textbook, which due to space limitations I can’t hope to exhaust. So, I’ll just mention one example before wrapping up my review. I’m a fan of traditional Chinese fortune telling (I even wrote a blogpost on I Ching divination!), so I felt really excited to discover the author’s detailed introduction of the traditional Chinese time-recording system (i.e., the sexagenary cycle). 😃

Weighing up the pros and cons, I give the two syntax parts of von der Gabelentz’s textbook an overall rating of four stars. And this brings us to a final rating of the entire book as follows 👉

Conclusion

In this six-part post I have reviewed four 19th-century Chinese language textbooks. My ratings for them are summarized below (converted to numerical format):

| Title | Pronunciation | Characters | Syntax | Overall | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of Chinese Grammar | 1 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 3 | 3 |

| A Grammar of the Chinese Language | 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 |

| A Progressive Course of Colloquial Chinese | 4.5 | 1 | 5 | 3.5 | 2 |

| Chinesische Grammatik | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 4.5 | 1 |

Winner: von der Gabelentz

So, von der Gabelentz’s Chinesische Grammatik has the highest score, which it well deserves. And I’m not the only one who thinks so. As Wikipedia points out, the German-American sinologist Friedrich Hirth once made the following comment on the book (the following quotation is from the original source as the Wikipedia version isn’t quite accurate):

Of all the Chinese grammars so far published this is the most perfect, inasmuch as it unites with the fulness of Premare’s work (footnote: It contains in all about 4,000 examples) the scholarly clearness of Schott’s “Chinesische Sprachlehre.” (Hirth 1882, a ten-page review of von der Gabelentz’s 1881 Chinesische Grammatik, p.237)

Wikipedia also cites Christoph Harbsmeier’s (1995) comment that von der Gabelentz’s book “remains until today recognized as probably the finest overall grammatical survey of the Classical Chinese language to date.” It seems von der Gabelentz’s work has remained the best of its kind for over a century. 👏

My wish

I got curious about old Chinese textbooks during a casual chat with a friend but then ended up writing such a long post 😝. It has been a journey of learning and discovery. And in hindsight, a most important factor that has supported me through the process is the realization that, compared to modern textbooks, these 19th-century ones are neither stingy in information nor contrived in style. I could really feel the profoundness of the Chinese language as well as the authors’ willingness to impart that profound body of knowledge to the reader.

In fact, I think both von der Gabelentz’s book and Wade’s book can still be very helpful to Chinese learners today, both to foreigners and to native speakers. What’s more, they actually make a great combo, since they respectively focus on Classical and colloquial Chinese. Of course, they would need a stylish makeover 💃 to appeal to modern students, who tend to love colorful pages with fancy layouts (like the page below 👇), but the main texts, especially the five-star ones, don’t really need much modification. Perhaps the next best-selling Chinese language textbook will be a 21st-century Wade & von der Gabelentz! 👑

My recommendations

But even if they don’t get “upgraded,” I’d still recommend them to Chinese learners, especially to learners who would like to gain a deeper understanding of Classical Chinese grammar and the Chinese writing system. My specific recommendations are as follows:

- For a diachronically grounded understanding of Chinese pronunciation (especially for the entering tone) read the pronunciation part of Chinesische.

- To learn about the initial design of the Wade-Giles romanization system read the pronunciation part of Progressive.

- To learn more about the Chinese writing system (i.e., stuff modern-day textbooks don’t normally teach) read the character parts of Elements and Chinesische.

- To get a thorough understanding of Classical Chinese grammar read the syntax parts of Chinesische.

- To learn authentic 19th-century Beijing Mandarin read the syntax parts of Progressive.

- To learn about the differences between Modern and Classical Chinese read the “newer language” part of the beginner’s version of Chinesische.

- If you wanna know everything, then read everything (except Grammar). 🙃

- If you want a real cool Chinese-English dictionary to aid your study, the author of Grammar (i.e., Morrison) has a superb one that contains a surprisingly large number of ancient and variant character forms.

In fact I like Morrison’s dictionary so much that if I had a Tardis I’d go back to the 19th century and ask him for a signed copy of it! 🙏😄

==The End==

Leave a comment