Lately I’ve been reading a book entitled The Spirit of the Chinese People (Chinese title: 春秋大義). It’s a collection of essays written by the famous Chinese scholar GU Hongming (辜鴻銘), who lived in late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. As is usually the case with literati of that era, GU was an expert in multiple disciplines; but what made him stand out was his impressive talent in language learning. According to Wikipedia:

He was fluent in English, Chinese, German, Russian and French, and understood Italian, Ancient Greek, Latin, Japanese and Malay.

Who was GU Hongming?

(source: Wikimedia Commons)

GU’s mastering of multiple languages clearly had to do with his life experience. Being born in a bilingual family (father Chinese and mother Malay-Portuguese), he went to Scotland for education at the age of ten (up till university), followed by further education in Germany and France. So, compared to his peers he had a very good language-learning environment to begin with.

GU’s success with languages also had to do with his unique way of learning, which is widely known in China even today (see this popular article if you can read Chinese). Yet few people are able to follow suit, for the lack of perseverance and an excellent memory, because GU learned languages by reciting entire literary works. Incidentally, that’s also the pedagogical method used in traditional Chinese elementary schools throughout many centuries (not in teaching foreign languages but in teaching Chinese).

In Chinese there’s a chéng yǔ (成語) or four-character idiom 倒背如流, meaning that someone knows some text so well that he can fluently recite it backwards. Albeit an exaggeration, this idiom well reflects the recognition of the learning-through-reciting pedagogical method in Chinese history as well as the society’s admiration for those who excel at it. Actually reciting is still an important part of language education in Chinese schools today. School children are required to recite paragraphs or even entire passages from grade one! I remember one of the first passages we were required to recite was the Classical Chinese poem 靜夜思 ‘Quite Night Thought’ by LI Bai.

“The Chinese language”

Being the third essay in The Spirit of the Chinese People, “The Chinese language” comes after “The Chinese woman” and precedes “John Smith in China.” In this essay GU mainly writes about his thoughts on the uniqueness of the Chinese language. His main argument is that Chinese is “a language of the heart,” which is difficult “not because it is complex, but because it is deep.”

Things I doubt

Some of GU’s language-related ideas are not exactly correct, at least from a contemporary linguistic perspective; but again, GU is neither contemporary nor a linguistician, so that’s understandable.

For example, GU writes in the beginning paragraph of the essay that “[t]he colloquial or spoken language [of Chinese] is the language for the use of the uneducated, and the written language is the language for the use of the really educated,” whereby he concludes “half-educated people do not exist in this country.” Then, in the next paragraph he further confirms that “spoken or colloquial Chinese is … the language of a child.” He backs up his point by an example of language acquisition:

[W]e all know how easily European children learn colloquial or spoken Chinese, while learned philogues and sinologues insist in saying that Chinese is so difficult.

Based on this example he gives foreigners who want to learn Chinese the following advice:

Be ye like little children, you will then not only enter into the Kingdom of Heaven, but you will also be able to learn Chinese.

While it’s true that children learn Chinese fast and that one should learn languages like children do, this can hardly be used as evidence that Chinese is a child’s language—because children can learn any language fast…

For another example, GU thinks “[s]poken Chinese is … an extremely simple language” in that it has “no grammar or any rule whatever.” What he had in mind might be the sort of “grammar” in European languages, which is basically morphology, but it’s incorrect to equate a morphologically poor language like Chinese (or English as well to some extent) with a grammarless/ruleless language. From a general linguistic perspective, a language has rules as long as its expressions aren’t totally chaotic, and in that sense all languages have rules.

Besides, GU’s attribution of Chinese as a “deep” language is vague, because he never gives that term a sound definition. He explains that Chinese is “a language for expressing deep feeling in simple language,” but isn’t that doable in just any language—depending on what each cultural community perceives as “deep feelings”?

It’s true that English can’t express the kind of poetic images characteristic of Classical Chinese poems (see my award-winning essay for some examples😊), but Chinese is also clumsy in expressing many disciplinary concepts that originated in the West (which is why many Chinese students, me included, prefer reading English textbooks). And if deep means poetic/romantic, then there are surely also many “deep feelings” that can be easily expressed in other languages but not in Chinese; for example, this web page lists the Yaghan word mamihlapinatapei, the Scottish word tartle, the Brazilian Portuguese word cafuné, among others.

- manihlapinatapei: a wordless yet meaningful look shared by two people who both desire to initiate something but are both reluctant to start

- tartle: to hesitate while introducing someone due to having forgotten his/her name

- cafuné: to tenderly run one’s fingers through someone’s hair

(original source: altalang.com; see also Simpson 2019 Language and Society, pp. 314–315)

Things I like

One major point made by GU that I find appealing is his stratified classification of the Chinese language based on the social-hierarchical context of usage. GU’s classification is as follows (he even designed Latin names for them😆):

- Spoken or colloquial Chinese

- Written Chinese

- Plain-dress written Chinese (litera communis or litera officinalis)

- Official uniformed Chinese (litera classica minor)

- Full court-dress Chinese (litera classica major)

In contemporary linguistic terms the above classification can be taken as one based on register, and it’s definitely true that the lexicon and syntax of Chinese are highly sensitive to register—so sensitive that some scholars have even proposed a “register grammar” theory for Chinese.

To illustrate, to express the meaning “he is older than me” in Mandarin Chinese one would say (and I translate verbatim into English) “he than me age great” (他比我年紀大) in a daily conversation but “he elder than me” (他年長於我) in a context that requires more elegance. N.b. the different positioning of the phrase “than me.”

As we can see, in the “elegant version” of the above sentence not only is the word for “older” changed to a more elegant form, but the sentence structure is also changed to that of Classical Chinese (though clearly the speaker is speaking in Standard Mandarin!).

- Classical Chinese: verb + prepositional phrase

- Modern Chinese: prepositional phrase + verb

Such vocabulary and structure switches are a dime a dozen in the actual use of Chinese, and one needn’t be versed in Classical Chinese to be able to use them correctly, because they are simply part of the synchronic grammar of the language.

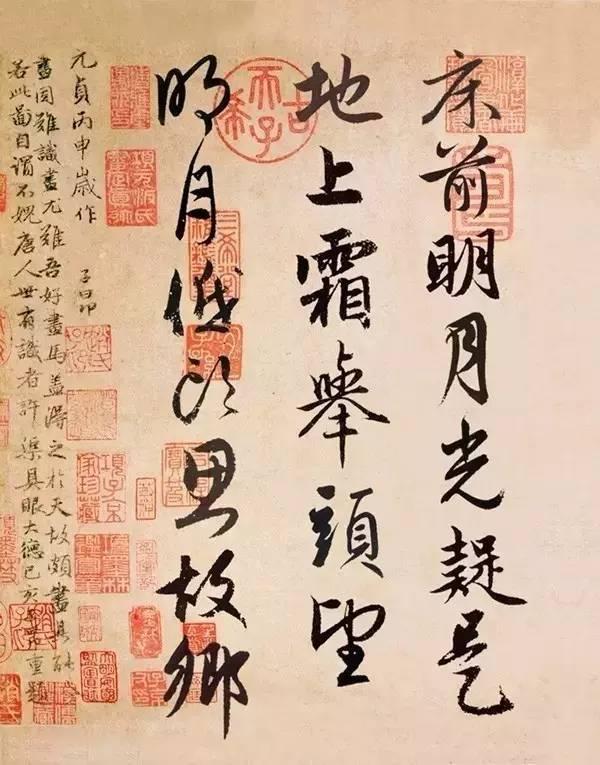

Another thing I like about GU’s essay is his verbatim glossing of Classical Chinese poems. Even though he doesn’t use any linguistic jargon, his glossing is actually better and more accurate than that of many professionally trained linguisticians. For example, in the following poem (excerpt)

誓掃匈奴不顧身 …… 猶是深閨夢裏人

swear sweep the Huns not care self … still are Spring chambers dream inside men

the character 身 is glossed as “self” instead of its literal meaning “body” because it’s used as a reflexive pronoun, and the character 裏 is glossed as “inside” instead of simply “in” (as in many contemporary linguistics papers!) because it’s not a preposition (though its meaning is close to a preposition in English-like languages) but a quasi noun (so “dream inside” really means “dream’s inside” or “the inside of the dream”). Given the precision in GU’s glossing, I have no doubt that he would also make an excellent linguistician if he lived in our time.

Of course, apart from the above verbatim glossing GU also gives a free translation of the poem, which is itself also a poem (in the English style)! I cite the entire translation below and highlight the parts corresponding to the above-cited exerpt:

They vowed to sweep the heathen hordes

From off their native soil or die:

Five thousand tasselled knights, sable-clad

All dead now on the desert lie.

Alas! the white bones that bleach cold

Far off along the Wuting stream,

Still come and go as living men

Home somewhere in the loved one’s dream.

I must admit I had to look up several words in the translation (e.g., heathen, tasselled)…😝 An overall feeling I’ve had while reading GU’s essays is that his English vocabulary is really remarkable, which perhaps has to do with the fact that he had learned the language via reciting literary works.

But again, I also feel that literati in late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China (e.g., LU Xun, CAI Yuanpei) were generally much better in whatever foreign language they learned than students today with similar educational resources, even though they didn’t have fancy tools like smart phones. Perhaps one really doesn’t need any fancy tools to become a good language learner—the human brain itself is fancy enough!🧠

Leave a comment