Civilizations in the universe come and go just like leaves on a tree grow and fall; neither ultimately leaves behind any trace. In Book III of the sci-fi novel The Three-Body Problem (三體 san1-ti3), when the solar system got attacked by an alien weapon called the dual-vector foil, which collapsed our 3D space into two dimensions at light speed, the last resort humanity came up with to preserve our civilization was, somewhat ironically, carving words into stone. And they didn’t do so on Earth but did it on Pluto, again ironically, since Pluto was the farthest (non)planet in the solar system from the center of the dimensional strike. In the author’s words:

文明像一場五千年的狂奔,不斷的進步推動著更快的進步,無數的奇蹟催生出更大的奇蹟,人類似乎擁有了神一般的力量,但最後發現,真正的力量在時間手裡,留下腳印比創造世界更難,在這文明的盡頭,他們也只能做遠古的嬰兒時代做過的事:把字刻在石頭上。

“Civilization was like a mad dash that lasted five thousand years. Progress begot more progress; countless miracles gave birth to more miracles; humankind seemed to possess the power of gods; but in the end, the real power was wielded by time. Leaving behind a mark was tougher than creating a world. At the end of civilization, all they could do was the same thing they had done in the distant past, when humanity was but a babe: Carving words into stone.” (Ken Liu’s translation)

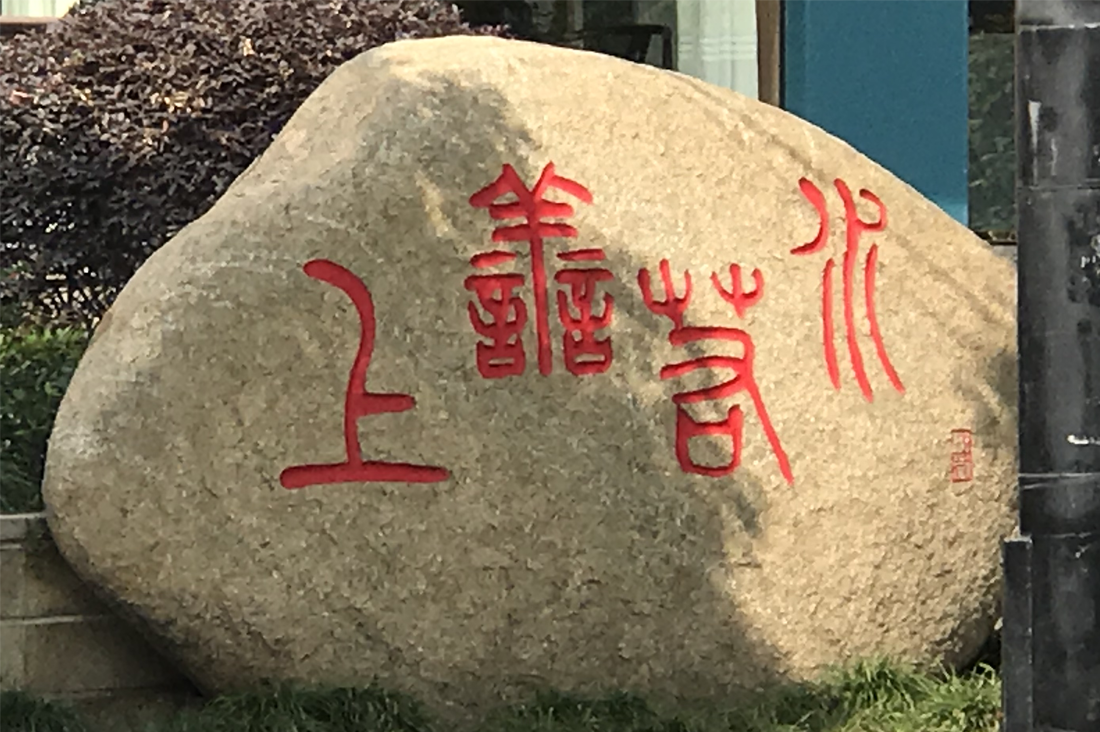

But of course even this most primitive method proved to be in vain, because 🌚🌚🌚 (spoiler alert! click to content). The Three-Body trilogy is truly epic, and I have mentioned it multiple times on this blog (for example, here). What reminded me of it this time, however, was something much more mundane—it was my accidental noticing of a stone carved with four characters sometime ago while walking on the street 😝. I didn’t dare touch the stone due to COVID-19 but did take a photo:

About the stone I saw

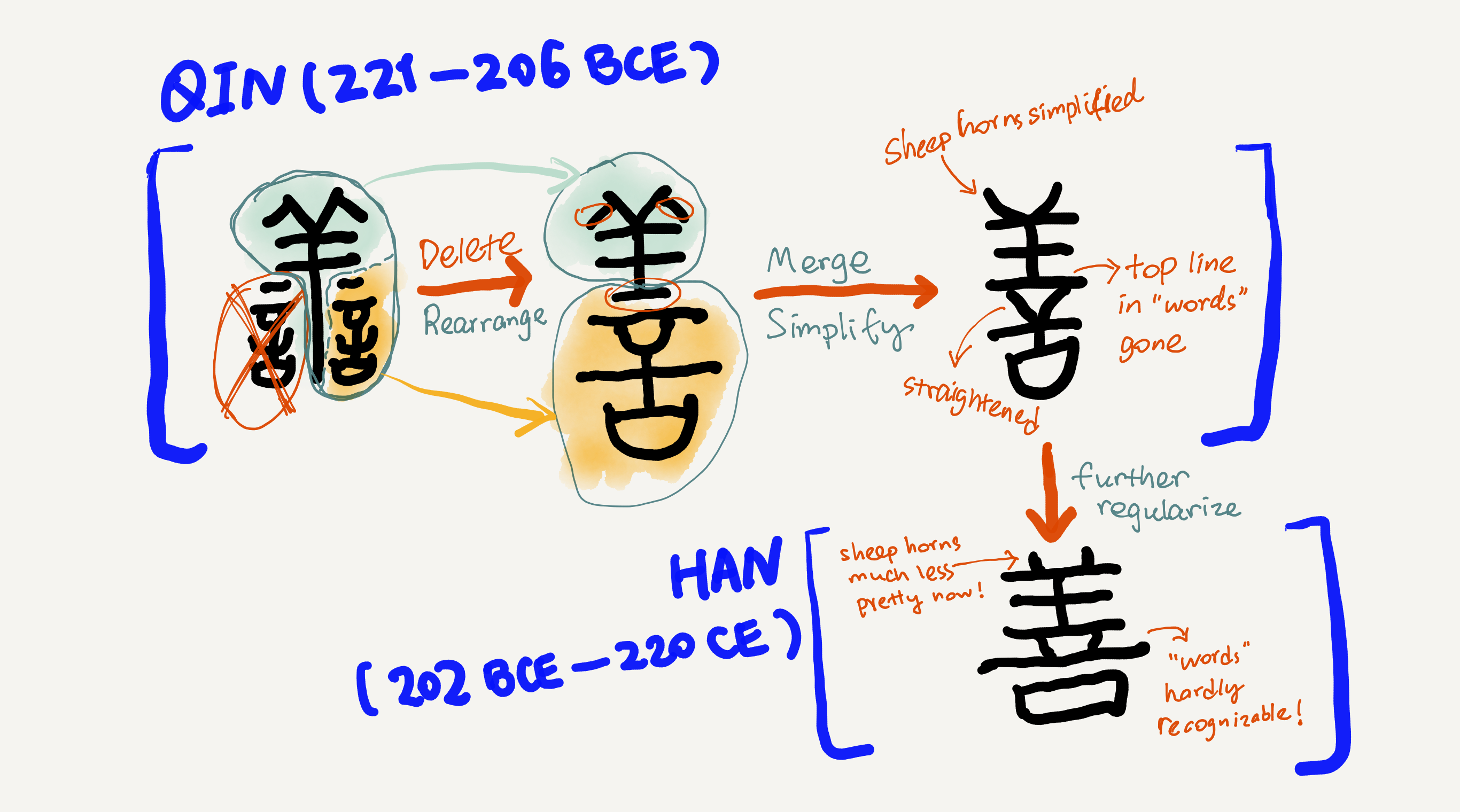

To be honest, I don’t think the seal script (篆書 zhuan4 shu1), despite its alleged literal meaning “the script for carving,” is easy to carve, because it has so many curved (NB not cursive) strokes and structural details. In the above photo, for instance, the second character from the left, namely 譱 shan4 ‘virtue’, has a sheep-shaped component 羊 (which indicates that the character is about something beautiful and auspicious) sticking into the narrow space between two side-by-side and identical components 言 meaning “words” or “speak.” The original meaning of the character was therefore “beautiful words” or “friendly conversations,” from where the meaning “virtue” was later derived (à la Shuowen Jiezi ‘Discussing Writing and Explaining Characters’).

(Note: For narrative convenience and in order not to make the post unnecessarily long-winded, here I’m mixing the historical development of writing systems and that of languages a bit. Strictly speaking, changes in word meanings are first and foremost driven by linguistic factors, not by factors in the writing system. One should also not think that the meaning of the word shan4 had been derived from the visual makeup of the character 譱, because logically speaking that word [or any other word], together with its sound and meaning, must have already been coined before a character was designed to record it. I’ll keep using loose talk here, but do bear this note in mind and don’t take things too literally when it comes to the relationship between word meaning and character meaning.)

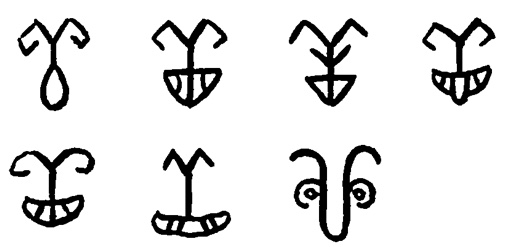

Interestingly, an alternative opinion (à la Jiaguwen Zidian ‘Oracle Bone Script Dictionary’) is that the seal-script character 譱 is actually a distorted descendant of the oracle-bone character for meal, which had a sheep component in it together with two eyes—so basically a quite beautifully drawn sheep head—but had no “words” components in it. On this view, the character came to mean “nice, auspicious” because people thought mutton was delicious. Despite the disputed background story and motivation, however, the development path of the character is undisputed. That is, scholars can recognize it in the numerous historical Chinese scripts without difficulty.

(Note: Both Shuowen Jiezi and Jiaguwen Zidian are highly respected historical Chinese script dictionaries.)

I personally am not sure how convincing either story above is, but the historical fact is that the variant with the “words” component won out and further evolved whereas the other variant with a beautifully drawn sheep head got forgotten quite early on—so early that it hadn’t even made its way into Shuowen Jiezi, which was compiled in the third century! But anyway, even though the variant with “words” had survived, it had also gotten simplified quite soon—still within the B.C.E. era—probably due to its structural complexity. So, one of its “words” components got removed and the other one got merged with the “sheep” component, and this simplified form has survived till today.

Since the seal script was too much work to carve and to write, it was really only favored by the royal and the aristocratic, who didn’t need to do the massive carving/copying work by themselves. Of course, this script does look very pretty and also preserves the original structures of Chinese characters more faithfully than the numerous later, simplified scripts. For this reason, it was declared the official script (正體 zheng4 ti3) of its time (i.e., Qin Dynasty). In fact, even two thousand years after it had lost its official status, it’s still commonly seen nowadays in various artistic contexts, as the stone I have randomly found demonstrates.

From seal script to regular script

After the seal script had lost its predominant status—basically with the demise of Qin Dynasty at the end of the 3rd century B.C.E.—the script that superseded it as the new official script was the chancery or clerical script (隸書 li4 shu1), so called because it greatly facilitated note taking and so was very beloved by government officials and scribes. Interestingly, the Chinese name for this script literally could also mean “the script of the slaves,” which allegedly is because prisoners in Han Dynasty (i.e., the dynasty after Qin) were often enslaved as scribes. And since the majority of those scribes were not well educated, the simplification of the Chinese writing system took place quite spontaneously. Scholars view the seal-to-chancery development as the biggest change in the history of Chinese characters.

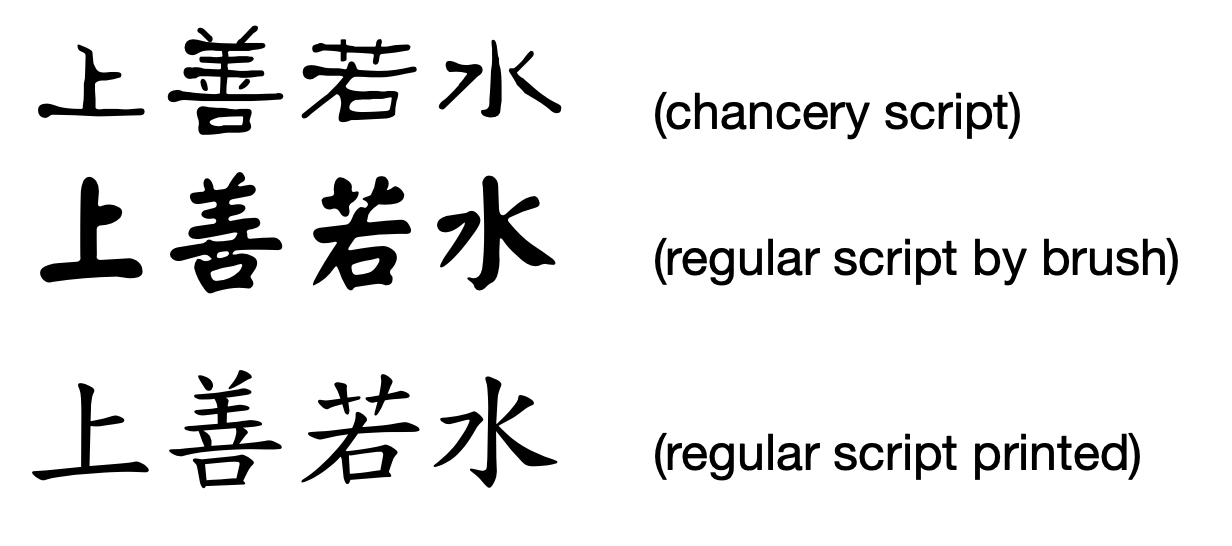

What is worth noting is that even though the Chinese script continued changing and evolving after Han Dynasty (which only lasted till the 3rd century C.E.), the basic structural characteristics of the chancery script managed to survive as the basis for all later scripts. Thus, the currently predominant “regular script” (楷書 kai3 shu1), which gradually gained momentum in the Southern and Northern Dynasties (5th century C.E.) and eventually matured in Tang Dynasty (7th century C.E.), doesn’t actually look very different from the chancery script. Below are the chancery-script form and two regular-script forms of the four seal-script characters above:

For the remaining content of this article see my next post Carving civilization into stone…and the “Chinese Rosetta Stone” (Part 2).

Leave a comment