Language learning is a lifelong journey. In particular, if a person speaks multiple languages and hasn’t acquired them all as mother tongues, then he must have learned some of them later in life, when his “factory language” is already set.

It’s not surprising that one can learn a third language via a second or, more generally, learn one nonnative language via another. I have the experience of learning Manchu partly via Japanese—from the book 満洲語文語入門 (‘A Primer of Manchu Written Language’)—because syntactically Manchu is a lot more similar to Japanese than to my native language Chinese, and so a textbook written from a Japanese perspective is much easier to follow. Similarly, I remember a Dutch professor of ours once mentioned that she had learned Japanese via Chinese, which is also understandable since there’s a large vocabulary overlap between the two languages.

Advantages and disadvantages

There’s a lot of online discussion about whether or not one should learn further languages via a nonnative medium language; see here, here, here, and here for examples. Long story short, below are the commonly assumed advantages and disadvantages of the practice:

Advantages:

- One can practice the second language along the way.

- Sometimes the target language is more similar to one’s second than first language.

- Sometimes there are more and/or better-quality resources in one’s second language, especially if it’s English.

Disadvantages:

- One may not be fluent enough in the second language to understand complex grammatical rules.

- Vocabulary learning is much easier via a first language, especially when the concepts involved are unfamiliar to the learner.

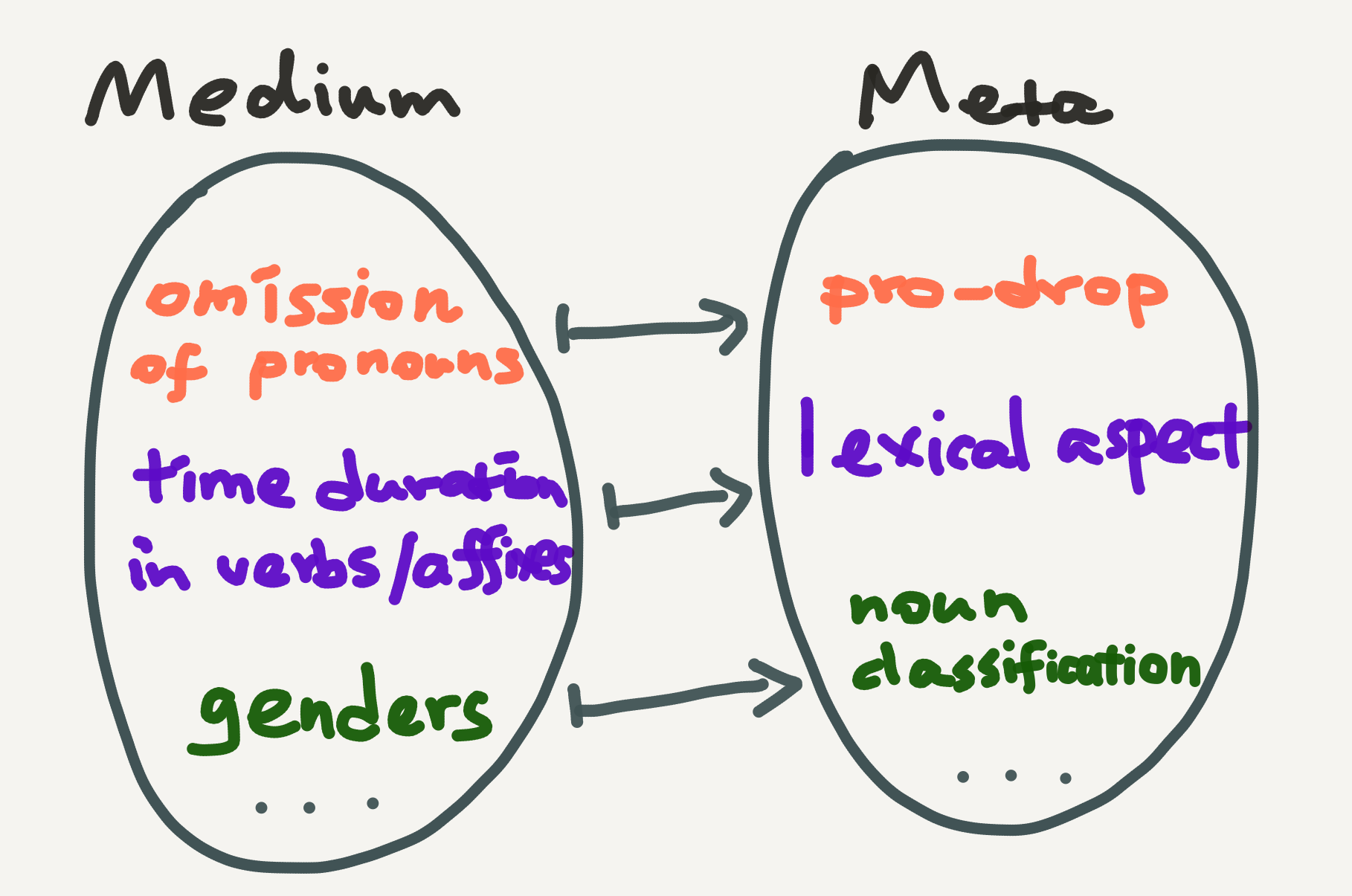

My experience of learning Manchu and our Dutch professor’s experience of learning Japanese both exemplify the second advantage above. Of course, neither of us is more fluent in our second (or rather n-th) languages than in our first. But being professional linguisticians, we aren’t really affected by that as far as rule learning is concerned—we understand the rules of natural languages on a meta-level anyway (see my Aug 5 post on how linguistics can equip one with a metalanguage). As such, when one wants to learn a third language via a second, linguistics can help reduce the two disadvantages of the practice to one.

Metalinguistic generalizations

More generally speaking, any rule-based component in language learning can be tackled more easily with the aid of linguistics. What’s more, for avid language learners linguistics needn’t even be taught, because everyone can come up with some intuitive linguistic generalizations after learning a few languages.

Every human is a born linguistician. Sensitivity to linguistic generalizations is hardwired into our brains.

Such generalizations may be preliminary or partial, but they work nevertheless (within a limited scope). The following comment from a trilingual person to someone curious about the difficulty level of Polish illustrates this point pretty well:

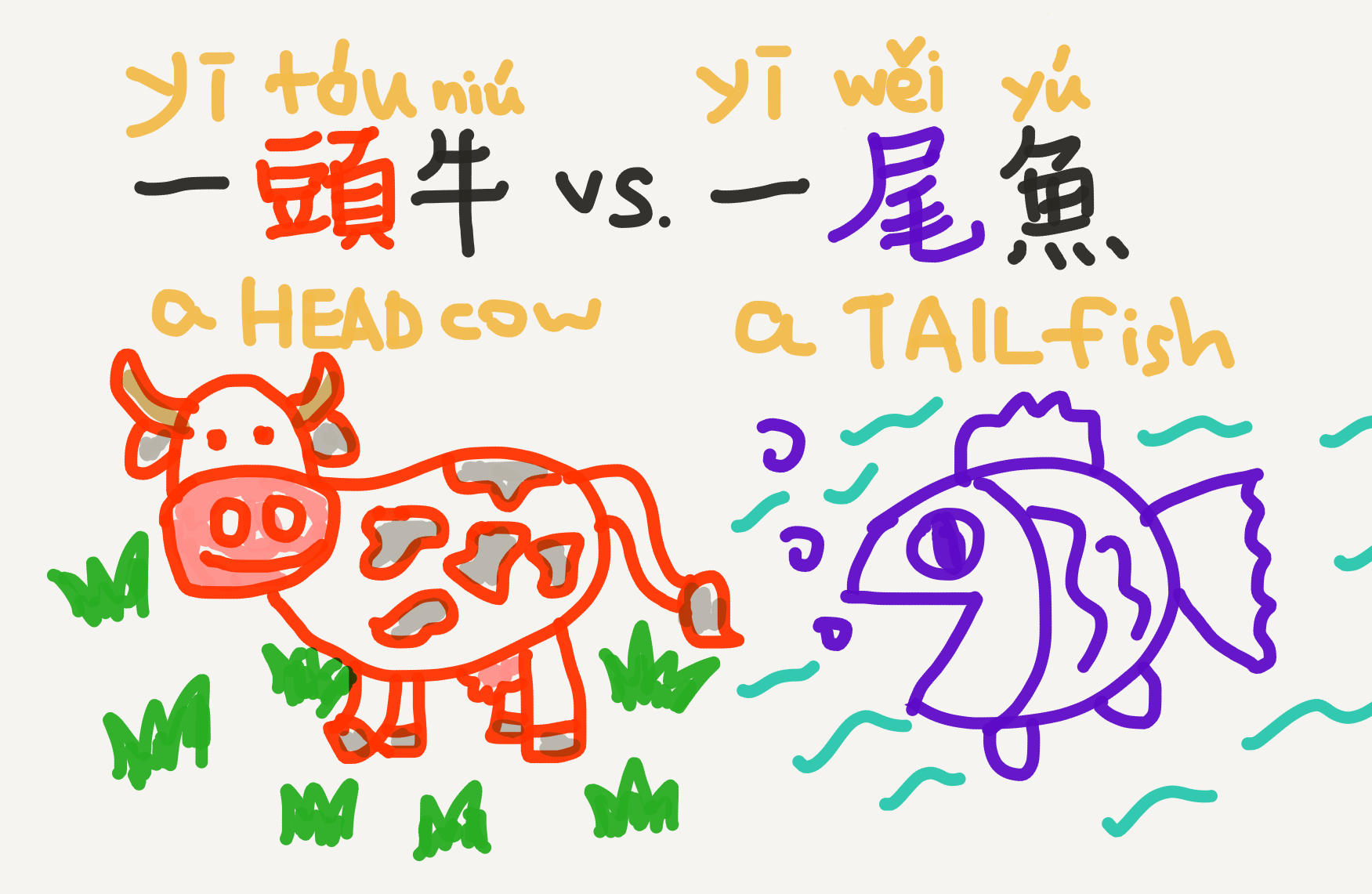

Oliwia: I see you’re learning German. Then keep the cases and add 3 more (7 in total, yes), keep all of the 3 genders, get rid of the nominative pronouns (much like in Spanish: you don’t use them unless you want to put some emphasis on the subject - which isn’t natural for many English speakers), keep of course the conjugation with 6 different pronouns/forms (like in Spanish, again), throw in tons of exceptions, double some verbs you have to learn depending on whether the action is short in time or long in time (like to take can be brać or wziąć), add prefixes and suffixes to verbs to add some subtlety in the meaning, use words that have almost no Latin or German roots hence not much in common with anything you know, and then you’re here. (source: Duolingo forum)

This is a nice summary of some key features of Polish grammar in comparison with German. A linguistician’s (aka my) “translation” of it would be something like the following:

Polish has 3 grammatical genders just like German but 7 morphological cases, including the 4 in German. Unlike German/English and like Spanish, Polish is a null-subject language and has a six-way morphological distinction in subject agreement. Aspect is a salient feature in the Polish verbal system, especially lexical aspect, which may be encoded in either verbal roots or derivational affixes. In addition, Polish, being a Slavic language, has a different set of basic vocabulary from that in German or Latin.

As we can see, the linguistician’s version is not substantially different; it just uses more technical terms, which can more accurately describe the grammatical points in question. Indeed, linguistics is just a systematization and further abstraction of preliminary, intuitive generalizations about human language. And good preliminary generalizations are an important foundation of good theories, which in turn make good predictions about our linguistic world and mind.

Three steps in grammar learning: a linguistician’s approach

Therefore, a big benefit of knowing the linguistic metalanguage is that it makes one much less reliant on the medium language in grammar learning. All one needs is a simple mapping from terms in the medium language—be it a first or n-th language—to concepts in the metalanguage.

With such a mapping in mind, one can leave medium-language-based rules aside and concentrate on learning examples, which can help fill in subtle details of the target language grammar, such as which verbal prefixes/particles convey what aspectual meanings, what nouns fall in which gender/class, and so on. For this purpose no medium is better than the target language itself, so just get immersed in it and build some “intuition”!😼

In other words, learning a new language via a medium language doesn’t mean being completely dependent on that medium. With some linguistic knowledge one can try the following three-step procedure in grammar learning:

- Map the terms used in the textbook to metalinguistic concepts.

- “Translate” the textbook rules to metalinguistic versions.

- Fill in subtle details not captured by textbook rules via immersion in examples.

Use multiple medium languages instead of one!

A linguistically informed learner has more freedom in choosing the medium language. For example, it doesn’t have to be one’s most fluent language. Even if you aren’t fluent in Russian, you can still learn Polish grammar via Russian with pretty good precision as long as you understand the metalinguistic concepts and have done the terminological mapping. Actually I wasn’t fluent in Japanese at all when I used it to learn Manchu—I could comprehend written Japanese much better than spoken Japanese, but that’s enough for a medium language in grammar learning.

Since the two cornerstones of language learning are rules and vocabulary, and vocabulary must be memorized anyway, a best strategy in medium language selection is actually not using a single one but combining several for separate purposes.

- For rule learning, choose the medium language that maximally facilitates the textbook-to-metalanguage terminological mapping. As of 2019 the best medium language in this respect is English, for the metalanguage itself is most extensively documented in English, as are all popular programming languages.

- For vocabulary learning, choose the medium language that maximally facilitates your grasping of the relevant real-world concepts. This is usually your first or most comfortable language, hence the wide agreement that vocabulary learning is much easier through mother tongues.

Knowing a suitable second language can sometimes be useful for vocabulary learning as well, especially when there is considerable overlapping between its lexicon and that of the target language (e.g., Portuguese/Spanish, Chinese/Japanese). However, this kind of usefulness doesn’t come from the linguistic metalanguage. Knowing that Portuguese and Spanish are both Romance languages and hence share vocabulary doesn’t help you learn Spanish words unless you already know Portuguese (and vice versa).

What schools can do

Well, basically, schools can start teaching linguistics. See more on this point in my Aug 5 post. Students can benefit a lot from a linguistics course in school, especially if they expect to learn new languages via a nonnative language later in life.

The benefits of teaching linguistics in school are especially real in our time, when most young people’s second language is English, which happens to be the international “interface language” for linguistics (or any modern discipline). Once the metalanguage is “installed,” one can quickly grasp new grammatical rules via English textbooks, however exotic they may appear. To quote Lauren Gawne’s words from her Superlinguo blog:

[T]he more you learn about how languages work, and acquire terminology to talk about it, the more exposure I had to languages that were very different to English. This has made me more comfortable with learning new languages, because instead of finding things really odd in comparison to English I’ll think to myself ‘woo, I’m finally learning an ergative language!’

Perhaps most people still prefer learning new languages via their mother tongues, but sometimes that’s just not an option. A realistic problem many language learners face is that there aren’t enough resources available in their native language. The following table shows the number of textbooks available if a Chinese person wants to learn certain languages via Chinese:

| Language | Textbooks in Chinese |

|---|---|

| Dutch | 2–3 |

| Hungarian | 1 |

| Icelandic | 0 |

In particular, I remember the Icelandic major in my undergraduate university in Beijing adopted an English-based textbook for freshers; and Icelandic wasn’t the only major doing this. By comparison, how many textbooks are available for the above languages in English? The European Bookshop alone lists 7 for Dutch, 4 for Hungarian, and 3 for Icelandic1 —and there are also high-quality Internet-based resources like Icelandic Online.

Nowadays it’s not difficult to get English-based textbooks. However, having access to a textbook doesn’t equal having access to its content. The English level of high school graduates in China isn’t low (especially in reading comprehension), but since no linguistics is taught in school, being good in English isn’t of much help when it comes to learning a whole new language via English—most students still have to rely on lecturers’ explanations in Chinese to understand the rules in the textbooks.

This situation makes self-study difficult and adds to the existing inequality in language education.

The picture would be a lot different if high school graduates were equipped with not only a fairly good mastering of English but also a basic understanding of general linguistics. I’ve mentioned above that a linguistically informed language learner has more freedom in choosing the medium language and is less affected by fluency level. So, knowing some linguistics not only reduces the disadvantages of learning a third language via a second but also reinforces the advantages of the practice.

The need of our youngsters to learn foreign languages is unlikely to decrease in the near future. If so, why not offering them some scientific knowledge about language in school to make their lifelong language learning journey easier and more enjoyable?

Takeaway

- One can and sometimes has to learn a third language via a second.

- Linguistics helps ease this process by providing a metalanguage, which makes learners less reliant on the medium language.

- For someone with linguistic knowledge, the current best medium language for grammar learning is English, and the best medium language for vocabulary learning is their native language.

- The young generation could benefit a lot from a linguistics course in school.

Leave a comment