In my previous post “Vowel harmony… and why linguistics matters in language learning (Part 1)” I wrote about my recent chat with a polyglot friend about vowel harmony as well as my thoughts on why linguistic knowledge can help one learn languages more efficiently. In this post I’ll continue to specify some particular scenarios in language learning where knowing some linguistics can really make a difference. I’ll also touch on the issue of linguistics education in schools. Hope you’ll enjoy reading!😃

Three scenarios in language learning where linguistics can help out

1. When you want to learn multiple languages simultaneously

A first scenario where some linguistic knowledge becomes really handy is when you want to quickly become a polyglot. Sure, there are people who can pick up new languages like having meals, but for most of us it takes months or even years to establish a systematic understanding of a single language!

For example, in an ordinary school or university syllabus the present tense and the past tense may be taught in different grades, and things like the subjunctive mood are usually left till much later. However, once you know how tenses and moods—or TAM systems in more linguistics-savvy terms—work, it takes no more than a day to figure out which tense/mood categories and what combinations thereof a language makes use of. Such an extra layer of understanding puts you in a much better position when you go into the practice-makes-perfect process.

What’s more, with the extra linguistic knowledge you won’t fear confusion across languages anymore. For example, students learning German often find the case system intimidating, especially if their native languages don’t have anything similar (say, Chinese). And when a Chinese student who has just learned German for a while wants to also learn Russian, he most likely will get intimidated again, for Russian has six cases. The intimidation won’t stop when he tries to learn even more exotic languages like Hungarian (where there are some 20 case-like categories) or Basque (which has a totally different case system from that in the familiar Indo-European languages).

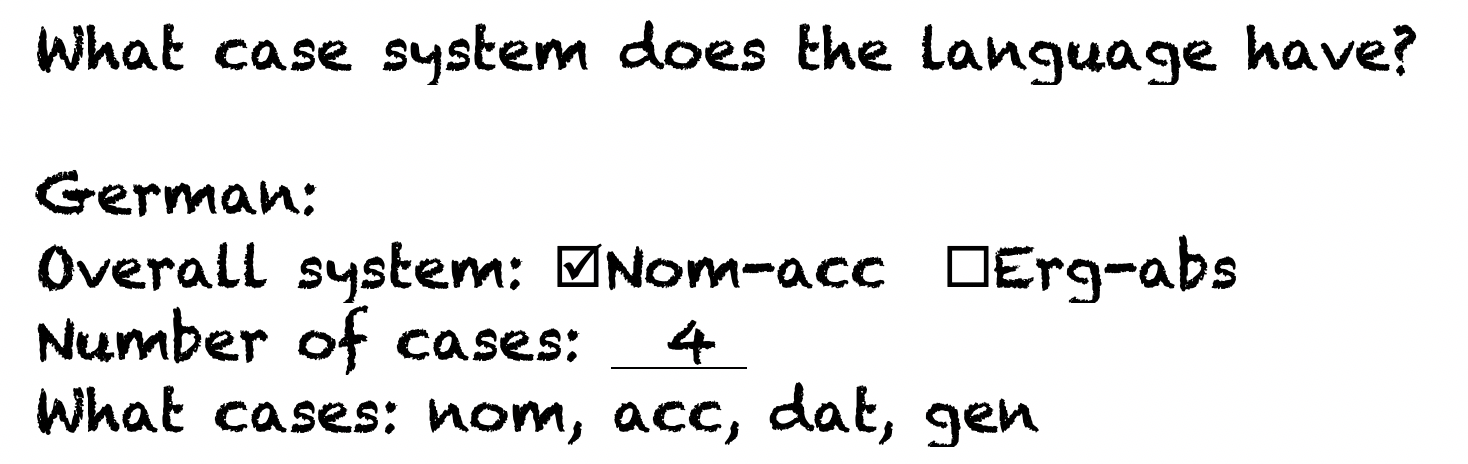

If you already know how case systems work in human language, however, all you need to do is check a few things for each new language you wish to learn, like this:

And then the remaining work is simply to figure out how each case category is instantiated in the new language, which can be easily found in any textbook. In her blog post Lauren Gawne calls the kind of knowledge that enables a linguistician to quickly acquire new, exotic languages a “metalanguage,” which is like a blueprint for human language as a whole and can be applied to any particular language one wants to learn.

Linguistics gives you the metalanguage behind human language.

2. When you want to sound more native

A second scenario in language learning where linguistic knowledge—or at least linguistic awareness—can be surprisingly helpful is when you want to give your language skills some native color. This is more evident in spoken language than in written language, perhaps because it’s easier to emulate native pronunciation than native intuition.

heliawe in my previous post mentioned the experience of sounding more native by nasalization. I’ve had similar experience with French and Korean. With French I had long noticed that some native speakers would add a short breath at the end of words ending in [i] (so merci ‘thanks’ becomes merci[ç] and oui ‘yes’ becomes oui[ç]) and that [k] would be pronounced more like [kʲ] (so cas ‘case’ becomes [kʲ]as and publique ‘public’ becomes publi[kʰʲ]). With Korean, on the other hand, I had noticed that many native speakers would pronounce m and n at the beginning of words like b and d (so mweo ‘what’ becomes something like bweo and nugu ‘who’ becomes something like dugu). The YouTube video below illustrates this phenomenon pretty well:

In hindsight, the two French phenomena are just final vowel devoicing and velar consonant palatalization, and the Korean phenomenon is just denasalization. Phonetic details like these are seldom mentioned in language textbooks, but they are so common in native speech that learners would sooner or later notice and start wondering about them, and a series of questions may ensue:

- What are they?

- Are they part of the language or just my illusions?

- Why aren’t they explained in my textbook?

- Should I imitate them or not?

- etc.

Neither textbooks nor native speakers are likely to give out satisfactory answers to such questions, but linguistics can, as the relevant phenomena have all been scientifically studied.1

Linguistics can help you grasp richer details about the language(s) you are learning.

3. When you don’t have enough resources

A third scenario where linguistic knowledge can become helpful in language learning is when there are few good resources for the language you are learning (e.g., if you want to learn Inuktitut) or when there are plenty of good resources but you don’t have enough time or money to access them (e.g., you can’t attend language classes or travel abroad).

The resource issue is less of a problem in big cities but can be a real obstacle for students in suburban or rural areas. For instance, a recent news report (in Chinese) describes the English subject as “a mirror that reflects the gap between education in cities and in the country” in China.

When all you have is a single textbook, how can you make best use of it?

I experienced exactly this situation when I first started learning French in high school. Being in a small city in China, our school had no French lessons; nor did any other school in the area. And being in a boarding school, I didn’t have regular access to the Internet either. In fact, all I had access to was a copy of an old textbook and its accompanying tape, which I had randomly found in a local bookstore.

A lot of the terminology used in the book didn’t make sense to me, nor did the supplementary information I could find on the Chinese Internet (12 years ago!). For example, I remember the vowel [e] was introduced as a “close-mouth sound” (the literal meaning of the Chinese term 閉口音) and [ɛ] was introduced as an “open-mouth sound” (開口音). What confused me was, How could someone make a vowel sound with their mouth closed? Since questions like this were too many, I decided not to think about them and just went through the book by listening and imitating (which is also how I noticed the devoicing and palatalization phenomena mentioned above). It eventually worked well, but I felt like a parrot.

Now I know that the terms “close” and “open” describe tongue positions rather than the literal closing/opening of the mouth, but again, my French-learning process would have been much easier if I had known this (and many other linguistic points) in school.

The fewer resources you have access to, the more valuable linguistic knowledge is in language learning.

Schools should teach linguistics

Sadly, few schools worldwide have included linguistics in their curricula, even though the few that have do report that their students have benefited a lot. For instance, a high school teacher in Wisconsin, Suzanne Loosen, concludes her report “High school linguistics: A secondary school elective course” with the following paragraph:

To conclude, linguistics as a course of study provides students with a myriad of benefits. … Ultimately, my students leave high school having challenged many assumptions that people commonly make about language. They are more aware of the diversity of the world’s languages, they become more reflective of their own use of language, and they are curious to learn more about language in the future.

There are also professional linguists who are devoted to promoting the potential benefits of teaching linguistics in schools; see this blog article by my colleague Dr. Michelle Sheehan and the website of another linguistics professor Richard Hudson for examples. There is a widespread view that linguistics or grammar lessons are useless and a burden for pupils, but that’s not true. Suzanne Loosen included some student feedback in her report. One student Valentin G. said:

Linguistics has made me more interested in learning new languages and has also made it easier than before. Language is so important because it’s like a key to the world. Everybody should know about linguistics, and I for myself, cannot get enough of it.

Another student Kylie D. said:

Not only have the things I learned expanded my knowledge of the study of languages, but they’ve opened my eyes to ways the world works, and the way people of all different tongues can experience things with their language.

I myself have recently had the chance to teach a Chinese high school student some basic linguistics (mainly syntax), and I got exactly the same feedback. The student was eager to learn how human language works and also happy to apply linguistic knowledge to real-life situations, including language learning. What’s more, the student understood and absorbed theoretical points no slower than university freshers who haven’t had linguistics classes before.

School students enjoy and can understand linguistics. They should have a chance to learn it.

Conclusion

I realize I’ve written quite a lot and also deviated a lot from my starting point (i.e., vowel harmony), but here is the end!🤓 So, the take-home messages are:

- Linguistics doesn’t solve all problems in language learning, but it does make your other efforts more efficient and worthwhile.

- Knowing linguistics unlocks a shortcut to becoming a polyglot.

- Linguistics can help you understand more details of foreign languages in ways that ordinary resources can’t.

- Linguistic knowledge can offset the shortage of language-learning resources and thereby enhance education equality.

- Linguistics can and should be part of school education.

And last but not least:

- Vowel harmony is cool and my polyglot friend is awesome!👏

– The End –

- On French vowel devoicing:

- Smith, C. 2003. Vowel devoicing in contemporary French.

- Fagyal, Z. & C. Moisset 1999. Sound change and articulatory release: where and why are high vowels devoiced in Parisian French.

- On French velar consonant palatalization:

- Detey, S. et al. 2016. Varieties of Spoken French. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 131, 415.

- On Korean initial denasalization:

- My colleague Kayeon Yoo's blog article "Speaking Korean: to nasalise or not to nasalise, that is the question" on CamLangSci.

- Young Shin Kim's PhD dissertation "An acoustic, aerodynamic and perceptual investigation of word-initial denasalization in Korean."

Leave a comment