Yesterday a friend of mine mentioned in a Facebook chat that he had started learning Turkish seriously. He went on to tell me about the striking similarity in terms of “vowel harmony” he had spotted between Turkish and some other languages he already knew, such as Finnish, Hungarian, Mongolian, and Korean (yes he’s a super polyglot!). I could totally relate to his excitement. Among the languages he mentioned I only know two (Hungarian and Korean), but the similarity is hard to miss for anyone with some linguistic knowledge.

What is vowel harmony?

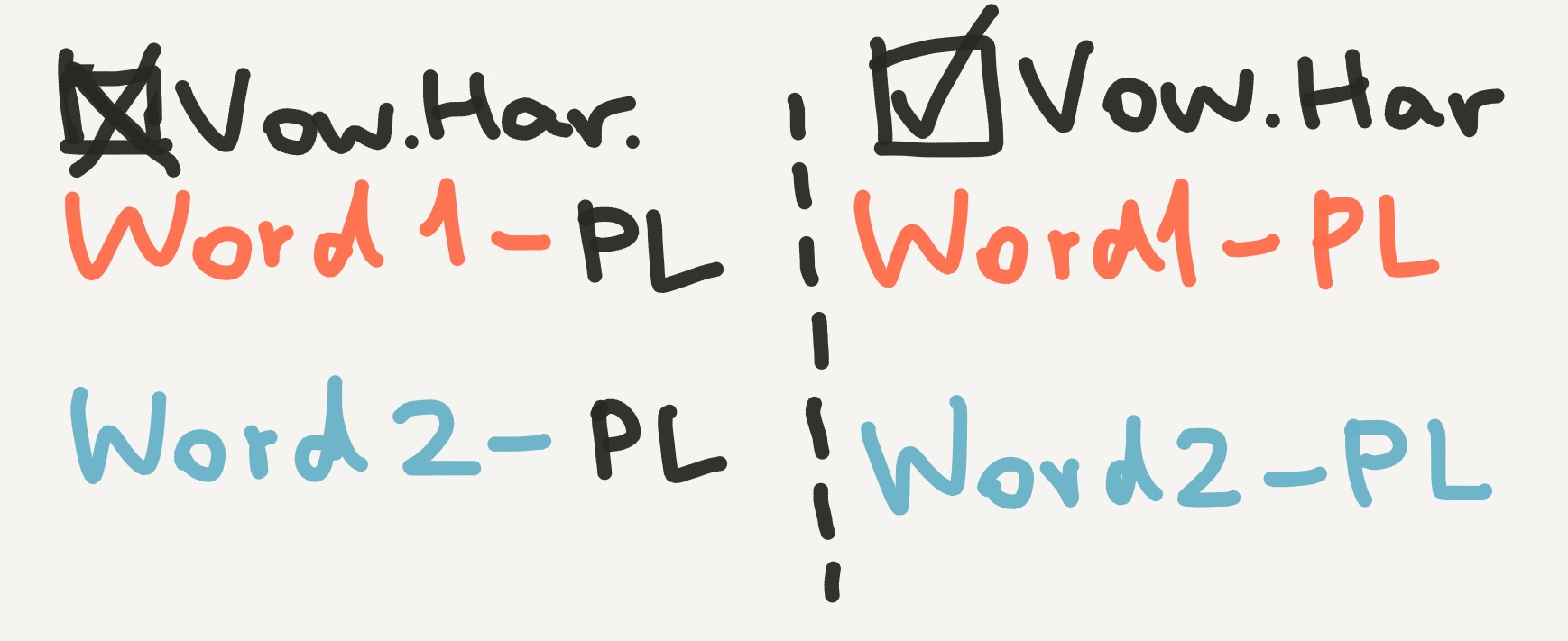

Vowel harmony is “an assimilatory process in which the vowels of a word have to be members of the same class” (Wikipedia). In plain English this basically means that grammatical elements (such as plural markers) adapt themselves to the nature of the vowels in the words they apply to. Such elements are sort of like “linguistic chameleons.”

Take Hungarian for example. The English prepositions to, for, of can be translated into Hungarian as the dative suffix -nAk. Note the “obtrusive” capital A; it indicates a chameleon slot that observes vowel harmony. Thus, the to in to Adam and that in to Daniel are different in Hungarian:

- to Adam => Ádámnak

- to Daniel => Danielnek

As we can see, -nAk becomes -nak when the preceding vowel (underlined) is á (a “deep vowel”) but becomes -nek when the preceding vowel is e (a “high vowel”). The detailed rules are more complicated, but this simple example well reflects what’s going on in a language with vowel harmony.

My friend’s excitement wasn’t about any particular rule in any particular language either. Rather, it was about the wide existence of a general pattern in world languages. Knowing the definition of vowel harmony and its basic mechanism equips him with an additional weapon when learning new languages.

Our brains love order, not chaos!

I still remember the first days in my Hungarian class, in one of the best language universities in China (the header image above is our cool library 😎). When we were first taught the concept of vowel harmony, students were generally fine with the á/e rule exemplified above, but when it came to é and especially i/í things began to get confusing.

In our textbook e, é, i, and í were all classified as high vowels and by the above rule should all take -nek in dative; but the reality is that words ending in é/i/í may take either -nak or -nek (e.g., senkinek ‘to nobody’ but kocsinak ‘to car’), which we had to memorize one by one, with a lot of trial and error and a conditioned sense of fear every time we saw a new word ending in é/i/í.

In hindsight, the linguistic truth is that these “problematic” vowels form a third vowel class (called intermediate or neutral) and are associated with a separate set of rules. Our textbook simply didn’t mention them! The human brain is naturally wired and gifted to appreciate logical things—things that “make sense”—and if language textbooks could include more linguistic knowledge (however conveyed), that would save learners a lot of time and frustration! (See more on this point in my next post.)

Linguistics helps in language learning

The usefulness of linguistic knowledge in the process of language learning is commonly acknowledged. Not only me and my polyglot friend but also many others have constantly benefited from a deeper understanding of how human language works. For example, a couple years ago someone asked this question on Reddit: Does a background in linguistics make language learning easier? I feel sympathetic to the following comments from the thread:

TimofeyPnin: Most definitely. The frustrating thing is realizing how much time I wasted in trying to learn languages with no knowledge of linguistics.

iwsfutcmd: The only language I studied before learning linguistics was a smidgen of French in high school, and when I look back to it, it feels like I was stumbling around in a dark room, finding my way around by feeling everything and shuffling slowly. After I learned some linguistics, it was like I turned on the light and could suddenly see the whole room.

knightshire: Dutch children and second learners have to memorize after which consonants a preterite verbs ends in a ‘te’ or a ‘de’ (similar to ‘t’ and ‘d’ in English). They use the mnemonic “ ‘t kof s chip “ which has the consonants t, k, f, s, ch [x] and p, to determine which has a t.

This whole memorization can be avoided by knowing that these are all voiceless.

heliawe: I live abroad and have learned the local language. I think that knowing what to expect in terms of phonetics and grammar and how to break those things down and analyze them has helped my language learning immensely.

One small example: I get compliments on my speaking pretty regularly, and I think one of the reasons is that I know to slightly nasalize everything. It makes the speech sound more like a native speaker. If I didn’t have a background in linguistics, I don’t think I ever would have picked up on that.

To clarify, I’m not saying that linguistics solves all problems and obstacles in language learning. Babies are equipped with no linguistic knowledge other than their born gift in picking up languages—or the universal grammar if you subscribe to that term—yet within just a few years they can master their mother tongues to a level that second language learners can only dream of.

Knowing linguistics certainly can’t help you control your muscles and produce a perfect palatal lateral [ʎ] (as in Italian) or uvular trill [ʀ] (as in German) either, just as knowing physics can’t help you actually walk on stilts. To achieve such goals you need regular practice.

What linguistics can help you with, however, is a better understanding and faster mastering of those components in language learning that do not come with practice. In other words, linguistics kind of helps you build up a higher-end spaceship. You must still train a lot before you can call yourself a captain, but once you’ve become one, a cutting-edge spaceship can obviously take you farther than a just-okay one.

Linguistics doesn’t save you the practice efforts in language learning, but it lifts your efforts to a higher dimension.

(source: Wikimedia Commons, by Paul Hudson from United Kingdom)

For the remaining content of this article see my next post “Vowel harmony… and why linguistics matters in language learning (Part 2)”.

Leave a comment