Today I came across an article online (via Facebook) entitled “More evidence that bilingualism delays symptoms of Alzheimer’s.” It introduces a recent paper published in the journal Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. Since I fear Alzheimer’s and happen to speak two(+) languages, I decided to do a bit of homework on this topic so that I can be better prepared as I age. I note down what I have learned from various sources in this and the next post.

Bilingual people get dementia later

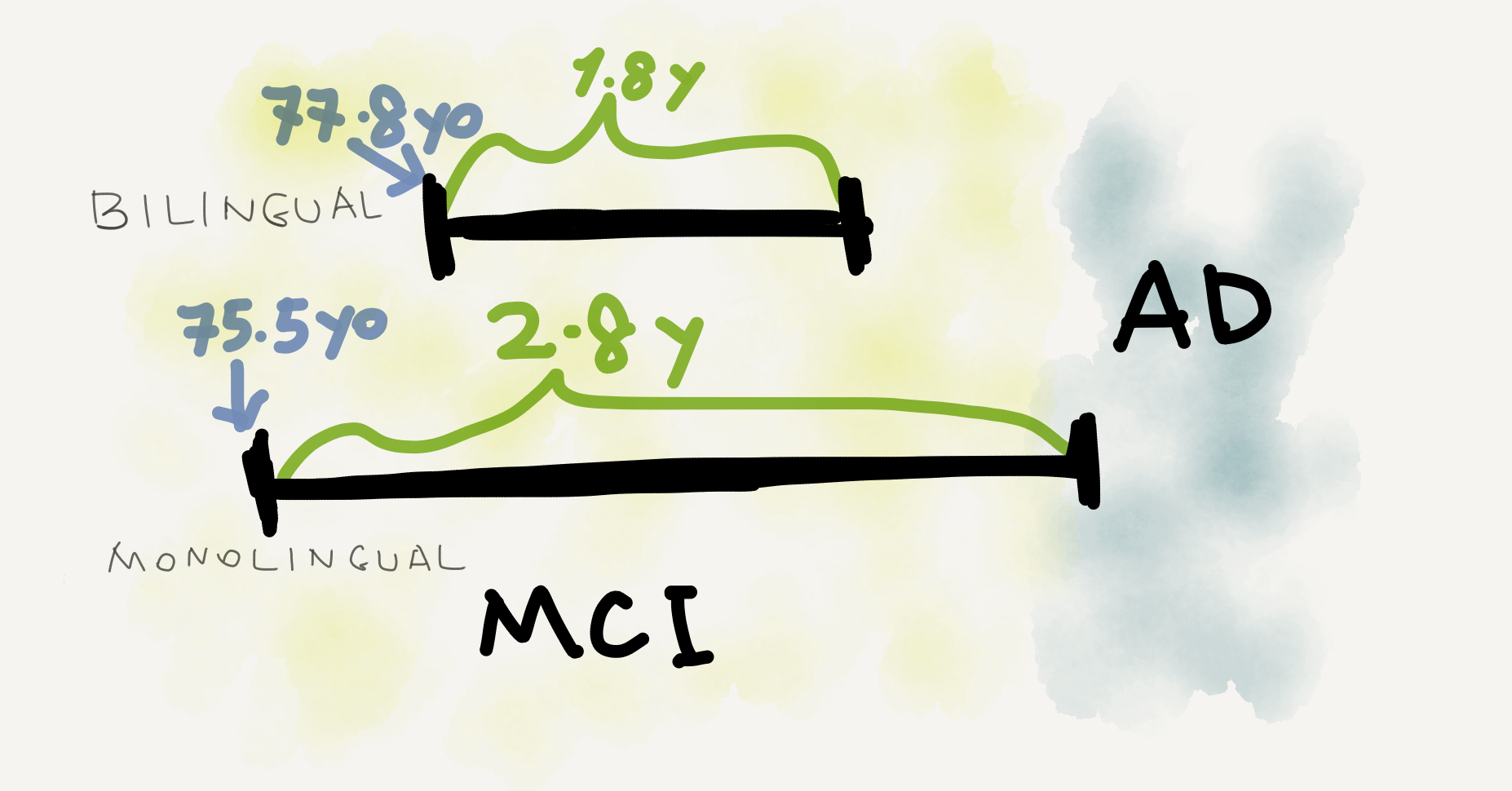

So, in the paper I came across researchers followed 158 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients, 75 bilingual and 83 monolingual, in a duration of 5 years and recorded the time it took for them to convert into Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The record shows that the bilingual patients got diagnosed with MCI 2.3 years later than the monolingual patients but converted into AD 1 year sooner. In other words, dementia symptoms manifest themselves in bilingual people later, but once they start showing up they deteriorate faster.

The paper concludes from this contrast in timing that there must have been more severe neurological damage in the bilingual patients’ brains at the time of their MCI diagnosis than indicated by their cognitive behaviors. This is taken as evidence that bilinguals are more resilient in dealing with neurodegeneration than monolinguals.

More studies on the “bilingual advantage”

The above-cited paper isn’t the only source advocating the cognitive benefits of speaking more than one language (here is a literature review). For nontechnical sources, I’ve found the following posts/articles among others (inside the boxes are the scientific papers they are based on).

- How a second language can boost the brain (Knowable Magazine, 2018)

Antoniou (2018) - language learning increases the volume and density of gray matter, the volume of white matter, and brain connectivity; learning a language in later life also helps - How bilingualism may protect against Alzheimer’s (Medical News Today, 2018)

Duncan et al. (2018) - being multilingual may contribute to increased gray matter in language and cognitive control areas and delay the cognitive effects of disease-related atrophy - Speaking a second language shows benefits in Alzheimer’s (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2017)

Daniela et al. (2017) - lifelong bilingualism contributes to brain cognitive reserve and thereby delays dementia onset; the crucial thing is to use two languages on a daily basis - Speaking More Than One Language Could Prevent Alzheimer’s (NPR, 2013)

Gold et al. (2013) - lifelong bilingualism can maintain youthful cognitive control abilities and offset age-related declines - Dementia delayed by speaking a second language (Medical News Today, 2013)

Alladi et al. (2013) - bilingual patients develop dementia 4.5 years later than monolingual ones regardless of education level; speaking more than two languages doesn’t bring additional benefits - The Bilingual Advantage (The New York Times, 2011)

Bialystok et al. (2007), Craik et al. (2010) - lifelong bilingualism maintains cognitive functioning and delays the onset of symptoms of dementia in old age, with no change in progression rate; to get the bilingual benefit one must use both languages all the time

In particular, Dr. Ellen Bialystok from York University (Canada) has researched on the dementia-delaying effect of bilingualism for decades (here is a relevant podcast episode). The human brain is amazingly elastic, even when it ages. What happens to bilingual people is that their constant shifting between two languages (aka code-switching) offers effective training of executive functions such as attention, switching, inhibition, and monitoring, all of which contribute to a higher cognitive reserve (Klimova, Valis & Luca 2017). And the higher the brain’s cognitive reserve is, the more resilient it is to pathological decline.

Opposing voices

The Alzheimer’s Association publicized 10 ways to love your brain on its website, including doing cardiovascular exercise, quitting smoking, getting enough sleep, and so on. “Learning a second language” isn’t included, probably because it’s not as easy to implement. But speaking a second language “might have a stronger influence on dementia than any currently available drugs” according to Dr. Thomas Bak from University of Edinburgh (who used to work at Cambridge)—though I’m not sure whether this statement is still true given the new drug approved by China.

Of course, we can’t exclude the possibility that the anti-dementia benefit of bilingualism is just an illusion, as has been pointed out by Kreuz & Roberts in their 2019 book Changing Minds: How Aging Affects Language and How Language Affects Aging.

Researchers who study bilingualism have long assumed that possessing two or more languages confers certain cognitive benefits in comparison to monolingual speakers. This bilingual advantage might manifest itself in a variety of ways, such as through better working memory or superior executive functioning. However, owing to the complexity of the issues involved, it is difficult to draw any unambiguous conclusions about a bilingual advantage.

— Kreuz & Roberts (2019), Chapter 5

Which second language to learn?

Anyway, the closest thing to language learning in the Alzheimer’s Association’s list is “formal education in any stage of life.” I’ll come back to the power of education later; here I’d like to put on my linguistician’s hat and ask a separate question—if an adult wants to master a second language to defy dementia, what would be a good choice? I’m asking because, strictly speaking, anyone who speaks an official language plus a local vernacular is de facto bilingual (and the situation is termed diglossia in sociolinguistics). In China, for example, the official language is Standard Mandarin (普通話/國語), while each region also has its own (multiple) dialects, many of which are mutually unintelligible.

Linguists say the Wu dialect widely spoken in Shanghai, to take one prominent example, shares only about 31 percent lexical similarity with Mandarin, or roughly the same as English and French.

— Howard W. French (The New York Times)

This means that the majority of Chinese citizens are already bilingual (or even trilingual) without learning any non-Chinese language, and the situation is even more salient in regions of ethnic minorities (there are 55 of them in China). However, that doesn’t make Chinese people less susceptible to dementia than people from other countries. On the contrary, according to a paper published in Journal of Market Access & Health Policy, as of 2015 there were approximately 46.8 million people suffering from dementia worldwide, 9.5 million of whom lived in China. The linguistic reality in China is obviously more complicated than simply a matter of bilingualism or trilingualism, but the above-described situation does suggest that the choice of the “second language” matters in studies on the relationship between bilingualism and dementia. This is something psycholinguists could take into account in future research.

Based on the executive function training account above, I guess the more different the second language is from one’s first language, the more effective it is in enhancing the brain’s cognitive reserve. From a linguistic perspective this means the two languages should be sufficiently different in vocabulary and in grammar. That is, they ideally should be from different language families (e.g., one Indo-European + one Sino-Tibetan) and of different morphological/syntactic types (e.g., one head-initial + one head-final). This might explain why speaking an official language plus a local vernacular doesn’t help that much, especially when the two varieties greatly overlap in vocabulary and grammar (e.g., Standard Mandarin and Northeastern Mandarin).

For the remaining content of this article see my next post “Bilingualism helps prevent dementia? And a remark on “scholarly longevity” (Part 2)”.

Leave a comment