In my previous post I wrote about the protective effect of bilingualism against dementia. I also mentioned that formal education was listed among the Alzheimer’s Association’s ten brain-saving activities. In this post I further look into the role of education in dementia prevention. I’ll also write down my thoughts on an observation made by my mom, which I call “scholarly longevity” for convenience.

Education vs. dementia

That education helps prevent dementia is a long-held belief, and scientific research on the issue has been going on for decades (here is a literature review). As a matter of fact, the protective mechanism of education is the same as that of bilingualism—both can enhance the brain’s cognitive reserve, which in turn offsets declines in brain structure as people age.

However, the benefit of education in terms of dementia prevention may not be as decisive as lifelong participation in cognitively stimulating activities, as recent studies have revealed (e.g., Wilson et al. 2013, Wilson et al. 2019). This is again similar to the situation with bilingualism, where lifelong code-switching is much more important than the learning experience itself.

It’s not education that prevents dementia but lifelong education.

As Dr. Robert S. Wilson from Rush University points out, formal education may not be as efficient as expected in preventing dementia because it usually ends many decades before the onset of dementia. By comparison, late-life activities that involve thinking and memory skills may be more important as people age. In particular, Dr. Wilson mentions learning another language among such activities.

That education apparently contributes little to cognitive reserve is surprising given its association with cognitive growth and changes in brain structure. However, formal education typically ends decades before old age begins whereas late-life level of cognitive activity (roughly analogous to schooling) has been associated with rate of cognitive change.

— Wilson et al. (2019)

“Scholarly longevity”

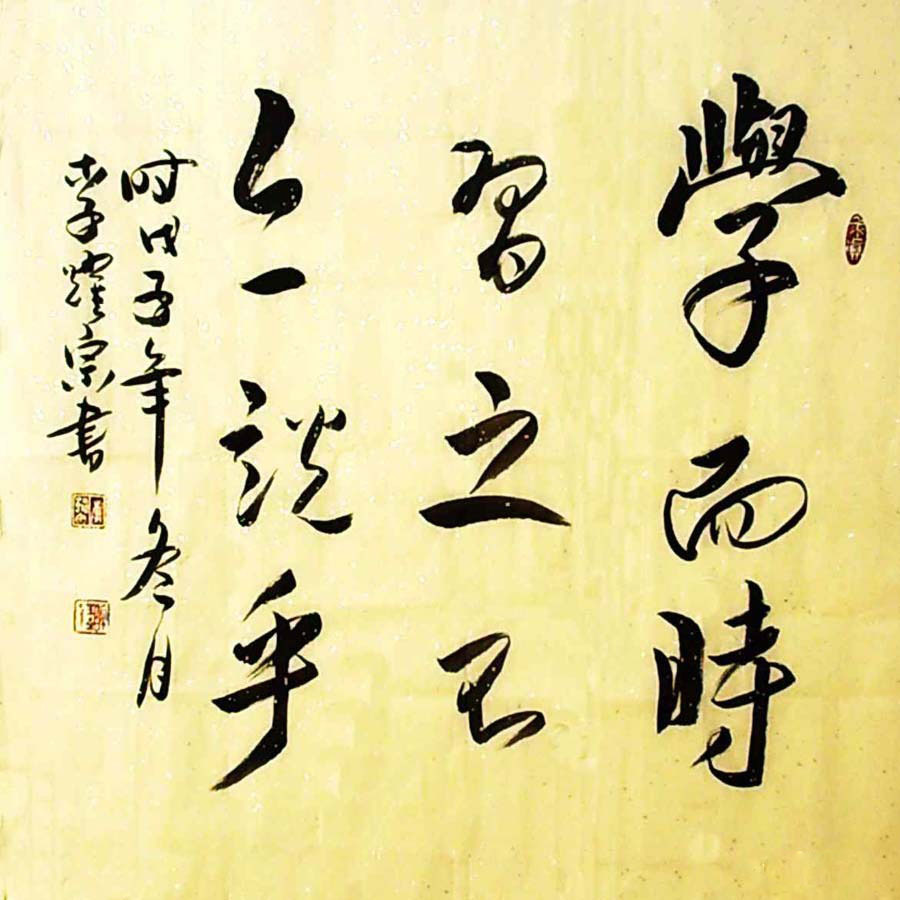

The above picture reminds me of an observation brought up by my mom in a recent family chat—distinguished scholars tend to live long, dementia-free lives. She cited several Chinese scholars as examples, including two linguists/philologists, JI Xianlin and ZHOU Youguang, and a physicist, QIAN Xuesen. All three scholars lived across three dynastic periods in Chinese history: the Qing Empire, the ROC (mainland), and the PRC.

| Scholar | Age at death |

|---|---|

| JI Xianlin 季羨林 (1911–2009) | 98 |

| ZHOU Youguang 周有光 (1906–2017) | 112 |

| QIAN Xuesen 錢學森 (1911–2009) | 97 |

My mom also named a few long-lived scholars who are still alive and engaged in scientific work, including two Nobel laureates, YANG Chen-Ning 楊振寧 (physicist, aged 97) and TU Youyou 屠呦呦 (pharmaceutical chemist, aged 89), and a world-renowned agronomist YUAN Longping 袁隆平 (aged 89).

For my parents’ generation such examples of quality old age can be both exciting and intimidating—exciting because they demonstrate that lifelong intellectual vitality is possible and intimidating because few people are lucky enough to make one of them. The more cruel side of the story is that for most senior citizens the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease doubles every 5 years after 65, and in China the average onset of the disease has shifted from 65 to 55 in recent years.

Scholarly longevity is a general phenomenon

Scholarly longevity doesn’t affect all scholars but seems to favor certain cohorts (otherwise academic would have become a most popular occupation on earth). I couldn’t find more recent statistics but found a 1969 report on the life expectancy of scientists, which collected information about scientists whose death notices appeared in Science in 1958–1968. During that decade, the average age at death for male scientists was 67.7 years and that for female scientists was 68.1 years. Among the disciplines appearing in the survey, the discipline with the highest life expectancy was archeology for men (76.7 years) and agriculture for women (84.0 years), and that with the lowest life expectancy was radiation for both men (61.8 years) and women (42.0 years). These figures are long out of date now, but they do suggest that some disciplines are more conducive to longevity than others.

Besides, scholarly longevity doesn’t seem to be a recent trend either but is evidently a phenomenon that can be looked at on a broader historical level. After hearing my mom’s observation, my first reaction was that it might just be a contemporary coincidence, for those distinguished scholars may simply have access to better living conditions. So, I tried googling for further examples of long-lived scholars. And to my surprise, scholarly longevity seemed to be a pretty regular pattern throughout Chinese history. For example, the table below shows information (from Wikipedia) of some well-known scholars living in Eastern Zhou dynasty (770–256 BCE), when the average life span was 30–40 years.

| Scholar | Age at death |

|---|---|

| Confucius 孔子 (551–479 BCE) | 73 |

| Mencius 孟子 (372–289 BCE) | 83 |

| Zhuangzi 莊子 (369–286 BCE) | 83 |

| Xunzi 荀子 (310–235 BCE) | 74 |

| Mozi 墨子 (470–391 BCE) | 79 |

China’s Eastern Zhou dynasty overlaps with the era of Socrates and Plato in Europe, and the two celebrated Western scholars also had relatively long lives. Socrates died at 71 and Plato at 81, and Socrates would have lived even longer if he hadn’t been unjustly executed.

Never too late to learn

Whichever era they live in, distinguished scholars usually have excellent educational background, so scholarly longevity may be further evidence that education helps prevent dementia. However, I believe what’s more important here is that they keep engaging in scholarly work even after retirement—and naturally also after finishing their formal education (getting a PhD is merely the first step in an academic career after all!).

For example, the above-mentioned ZHOU Youguang only quit his job as a banker and became a linguist at the age of 50. He then turned into a thinker at 85 and published five books between 100 and 110—that is, in the final decade of his life. As a more recent example, I saw in the news yesterday that a 95-year-old physics professor at Tsinghua University was happily delivering lectures via the Internet during the COVID-19 epidemic. Finally, as a linguistics student, I can’t help but mention Noam Chomsky, the most influential practitioner in modern linguistics and author of over 100 books, who is still giving cutting-edge lectures at the age of 91.

In sum, the cognitive reserve theory is most likely correct, but as both the case of bilingualism and that of formal education reveal, the real key to cognitive reserve enhancement and thereby to dementia-free longevity—that is, if we presume bodily longevity—is lifelong perseverance. In other words, for those of us who are neither scholars nor born in a bilingual environment, dementia-free longevity is pretty much a reward of diligence. So let’s keep learning!😃

Leave a comment