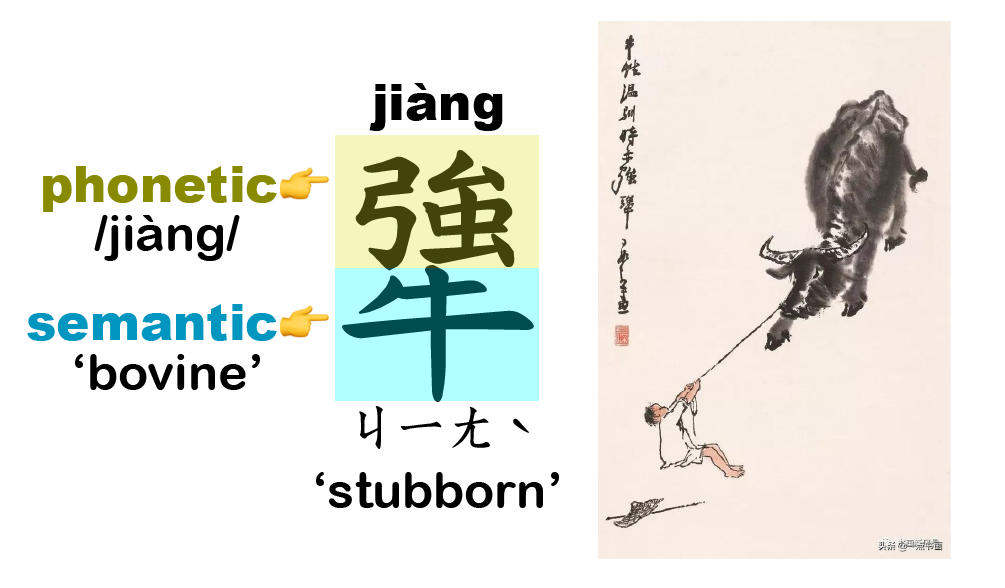

This is my first post of 2021, so first of all Happy New Year! And Happy “Niu” Year in advance to my Chinese-speaking friends too, since 2021 is a Year of the Ox (牛 niú). In Chinese astrology the niú—which is a generic name for all bovine species—is a symbol of diligence, strength, patience, dependability, and determination. It is believed that people born in Years of the Ox tend to enjoy great successes (though they are also believed to be born stubborn). 2020 was a hard year for many of us, so let’s hope the dependable niú will bring the world more good news in 2021. 🙏

Fun fact: Whereas in English someone stubborn is often likened to a mule, in Chinese they are often likened to an ox (among other animals)—to the extent that the character for “stubborn” itself has niú as its semantic radical.

Semi-loan neologisms in contemporary Chinese

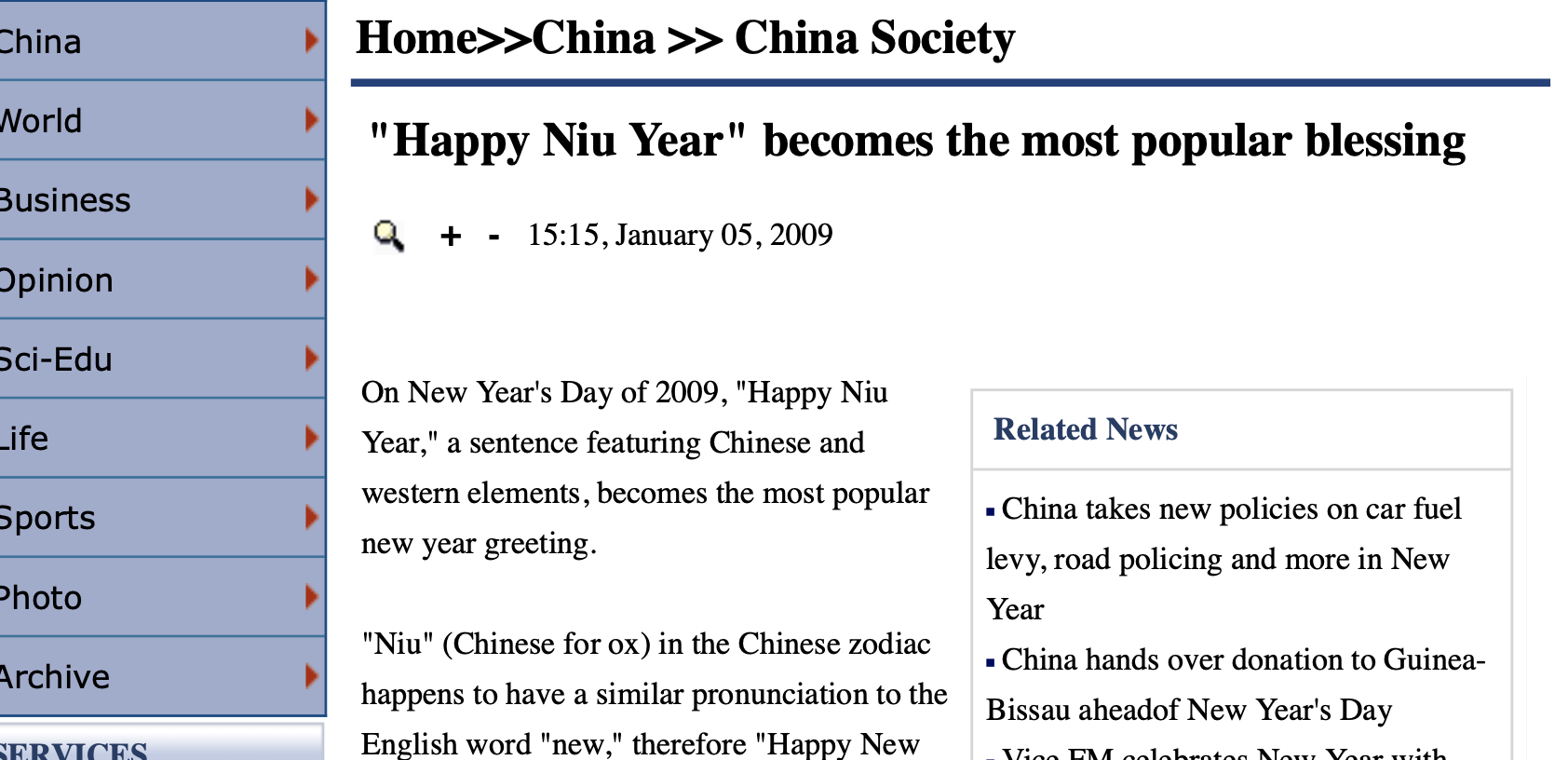

The slogan Happy Niu Year (or Happy 牛 Year as it’s written on the billboard at the top of this page) brilliantly plays with the new-niu pun. I remember it was already in popular use in 2009 (the last Year of the Ox). There was even a report on it in the online edition of People’s Daily, one of the most authoritative newspapers in China. And BBC English had an episode on it as well.

Crosslingual neologisms like this are on the rise in contemporary Chinese, especially on the Internet and in variety shows (which are a big thing in Asia). For example, an expression that I hear a lot these days is 立flag (pronunciation: lì flag), which literally means “to set up a flag” and actually means “to publicly declare a goal or a potential achievement.” Since it often happens that if one prematurely declares something it’ll eventually fall through, this phrase is often used with the extra sense of “jinx.”

Since the connection between the actual usage of the phrase and its literal meaning is rather vague, it may require some effort to get it through to someone who hasn’t picked it up “naturally.” For instance, on a recent variety show Our Song a young singer of my age tried to explain the phrase to an older singer of my parents’ age, and the following dialog took place (my translation).

Translation of a Chinese dialog on Our Song (link to video)

Y = young singer, O = old singer

…

Y: Don’t lì flag. I’ve been meaning to tell you not to lì flag since Episode 2.

O: I still don’t understand what /flæk/ means.

Y: For instance, when you say “I’ll certainly have good luck today” or “I’ll certainly pass the exam today.” This is called a flag.

O: /flæk/. Is /flæk/ English?

Y: Do you think it sounds like Mandarin?

O: Okay. /flæg/ is qí (in Chinese), right?

Y: Right. So don’t say “I’ll certainly do a great job today.” The flag will (gesturing falling down).

O: Ohhh! Then what is /li:f/?

Y: /lì/ is Chinese. 立, (gesturing a fluttering flag) flag.

O: Ohhhhhh! The first word is Chinese, and the second word is English: 立flag. Okay, 立旗 (lìqí, the fully Chinese version of the phrase). It’s 立旗.

Y: No, we don’t say 立旗. We just say 立flag.

O: 立flag.

…

Y: Great! Our teacher has finally learned the phrase 立flag in the 11th episode.

While watching the show, I didn’t expect that it would take the older singer (Hacken Lee) so long to learn the phrase, because he’s from Hong Kong and should be very sensitive to Chinese-English code-mixing—at least to the strategy, if not to the particular expression. But anyway he’s a fantastic singer and fans love him regardless. 🙃

A new type of loanword

Half-Chinese-half-English coinages like 牛year and 立flag represent a fairly recent phenomenon in Mandarin Chinese. Lexical borrowing or loanword is a widespread linguistic phenomenon that falls into many subtypes (see an earlier post of mine for a particular subtype in Chinese called “letter word”), and I think the above neologisms constitute a new subtype:

- They have regular syntactic structures (e.g., 立flag is a verb-object phrase).

- They are highly idiomatic, which is why one can’t easily guess their intended meanings even as a bilingual person.

- They resist full translation and only sound/look right as such.

Point 1 distinguishes these neologisms from simple loanwords like 巧克力 qiǎokèlì (chocolate). Point 2 distinguishes them from words made up of a loan root plus a native affix, which are commonly seen in languages like Japanese and Korean. For example, 勉強する benkyō-suru and 공부[工夫]하다 gongbu-hada both mean “to study” and both consist of a Chinese root plus a native verb-forming suffix. Point 3 distinguishes them from conventional semi-loan words like 因特網 īntèwǎng ‘Internet’ (īntè < Inter) and 打的 dǎdī ‘take a taxi’ (dī < taksi), where the loan parts are fully localized with substantial phonological adjustments.

This last point is particularly interesting, for semi-loan neologisms not only brutally blend Chinese and English without phonological/orthographical adjustments but also do so “proudly.” It isn’t immediately clear why this should be the case, since English isn’t an official or dominant second language in the Chinese-speaking regions where the relevant expressions are catching on.

I guess a potential factor behind the phenomenon is the unique nature of computer-mediated communication or CMC, where verbal and visual information-exchange channels are virtually fused. In this sense, semi-loan neologisms are a cousin of other types of CMC-specific slang, such as unpronounceable acronyms (e.g., zqsg, ncf; I’ve blogged on this), ubiquitous emojis (I’ve also blogged on this), creative uses of punctuation marks, and so forth. In a word, we might be witnessing something exciting in the evolution history of human language! 😃

More examples

As it happens, I just came across a YouTube video on this very topic two days ago, wherein a Chinese girl was explaining to a Korean guy the meanings of some popular Internet slang expressions. She mentioned the following items:

1. cue: bring up someone’s name in public (and the “cued” is expected to speak)

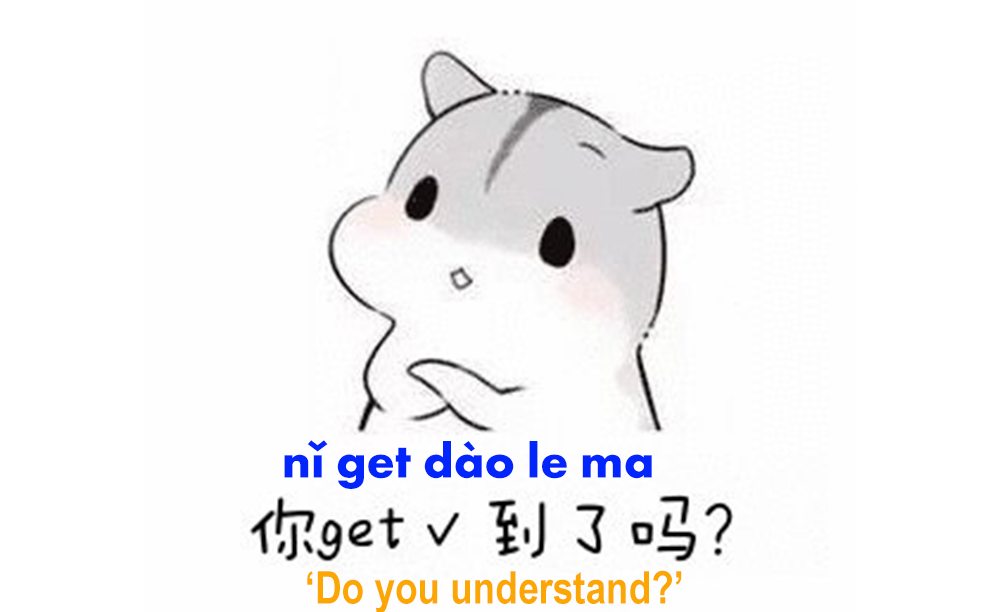

2. get到(dào): successfully acquire a new skill or learn some new knowledge

3. 立(lì)flag: [already explained above]

4. CP: a celebrity couple (whose relationship is usually imagined by fans)

5. C位(wèi): the central or most important position in front of the camera

These items apparently don’t all belong to the same formal class: cue is a simple loanword (which has kept its original orthography), get到 and 立flag are semi-loan expressions, while CP and C位 are letter words. Semi-loan expressions feel more unusual than the other two classes, probably because one has to consciously think about both English and Chinese when parsing or producing them.

In my personal experience, whereas I can get by by treating cue as an ordinary Chinese word (which happens to lack a character form) and treating the letters in letter words as language-neutral symbols (on a par with @, &, etc.), I can’t comfortably do so for semi-loan expressions but must consciously invoke my knowledge of both Chinese and English. As such, I think compared to simple loanwords and letter words, semi-loan expressions are more akin to code-switching (albeit a nontypical case, as I will remark below).

There are still many other semi-loan neologisms in contemporary Chinese Internet slang. Another one that readily comes to my mind is 打call (dǎ call), which refers to fans’ cheerleading-like screaming behavior at live concerts (as in this video) and can also mean “to enthusiastically support” in general.

The English part of this expression actually has its origin in Japanese (コール kōru), which means the immediate donor language in this case is Japanese instead of English (though コール itself is ultimately from English). That said, the verb phrase 打call ‘to root for, to cheer for’ is a native Chinese coinage, because コール in Japanese is mostly (if not always) used as a noun, whose corresponding verb is 応援する ōen-suru, a totally separate word.

A final example I’d like to mention is hold住 (hōu zhù), which had been coined quite early on in Cantonese but has only entered the shared lexicon of the entire Chinese-speaking world via a highly influential Taiwanese variety show Kangsi Coming in 2011 (video link). That show is therefore the de facto source of the phrase for many non-Cantonese Chinese speakers (myself included). The expression literally means “to take told of something” and actually means “to successfully handle a situation.”

Unlike the previous examples, this one actually involves some phonological adjustment in its English part, because hold is normally pronounced as /hōu/, with the final /d/ being truncated. However, the reason behind this truncation may not be completely phonological, because the /t/ in get到 (get dào) isn’t truncated despite the similar phonological context.

I guess a more likely reason for the truncation in hold住 is that when the /d/ in hold is pronounced, the phrase sounds almost identical to hold得住 hōu-de-zhù, which means “to be able to handle a situation.” While this meaning doesn’t feel so different from “to successfully handle a situation” in isolation, it causes all kinds of trouble in actual usage. For example:

你hold住了嗎?

nǐ hold zhù le ma

“Did you successfully handle it?”

Here if the /d/ in hold is pronounced, the sentence would sound like “Did you can successfully handle it?” which is ungrammatical. Besides, if the /d/ in hold is pronounced, then the derived phrase hold得住 would become /hold-de-zhù/, which contains two adjacent /d/’s and sounds awful (probably because it violates a phonological principle).

Chinglish or code-switching?

In the above-mentioned Chinese-Korean YouTube video, the hostess calls her examples “Chinglish,” but is this scientifically true? I don’t think so. Wikipedia defines Chinglish as “slang for spoken or written English language that is influenced by a Chinese language.” Since her example sentences are all from Chinese, they are by definition not Chinglish.

Of course, speakers may freely carry Chinese semi-loan neologisms over to English and say things like “The two actresses are fighting for the C position” and “Don’t set up flags,” which would then count as Chinglish. The case of 牛year is perhaps more complicated, because Happy Niu Year is apparently English but it as a slogan has only been used in Chinese contexts to my knowledge. Anyway, Chinglish is cool, and loanwords borrowed back and forth will make it even cooler. 👏

But if semi-loan neologisms in Chinese contexts are not Chinglish, then what are they? In other words, what is their linguistic status? Above I have mentioned that I personally feel they are more like code-switching (more exactly intrasentential or intraword switching), though not in the typical sense of the term.

In linguistics, code-switching or language alternation occurs when a speaker alternates between two or more languages, or language varieties, in the context of a single conversation. Multilinguals ... sometimes use elements of multiple languages when conversing with each other. Thus, code-switching is the use of more than one linguistic variety in a manner consistent with the syntax and phonology of each variety. Wikipedia

Semi-loan neologisms in Chinese Internet slang both comply with and deviate from the above definition. They comply with it in the basic formats of “more than one linguistic variety” and “consistent with the syntax and phonology of each variety” but deviate from it in at least four aspects:

- Environment: Typical code-switching happens in a multilingual society while semi-loan neologisms are occurring in a fundamentally monolingual society.

- Regularity: Typical code-switching happens regularly and affects entire conversations while semi-loan neologisms are far more occasional and only affect particular words.

- Lexicality: Typical code-switching happens on the fly in a rule-based manner (so communication is possible as long as all interlocutors have prior knowledge in the languages involved) whereas semi-loan neologisms are highly idiomatic and must be learned one by one (so prior linguistic knowledge alone doesn’t guarantee proper understanding).

- Pragmaticality: Typical code-switching happens on more literal levels (e.g., morphology, syntax) whereas semi-loan neologisms often encode extra pragmatic information.

Due to the above deviations, if semi-loan neologisms involve code-switching at all (which probably can only be ascertained via neurolinguistic experiments), it’d be a particular nontypical type of code-switching. So, our final conclusion seems to be that these cool expressions that are being constantly coined and widely circulated in the Chinese-speaking world fall somewhere between borrowing and code-switching as a linguistic phenomenon.

Since we are on it, I’d like to make a further comment on semi-loan expressions with Cantonese origins. Code-switching (in the typical sense) is rather common in Hong Kong due to the bilingual social environment there, and Hong Kongers have coined many semi-loan expressions (among other types of loanwords) since a long time ago, including the above-mentioned get到 and hold住 as well as many others that haven’t made their way into the common Chinese lexicon, such as 放(fong3)break ‘take a break’, 出(ceot1)trip ‘go on a trip’, and hang機(gei1) ‘(computer, phone, etc.) freeze’.

However, the popularity of semi-loan expressions (or rather that of all types of loanwords) in Hong Kong is a qualitatively different matter from that in other, non-English-speaking parts of China. The former is a natural result of language contact (and one that has been studied in depth by linguists) whereas the latter is an emerging phenomenon in the Internet era.

Takeaway

In this post I have written about some fashionable half-Chinese-half-English phrases that are popularly used online and in variety shows, such as 立(lì)flag ‘to publicly declare a goal or potential achievement (with the risk of jinxing it)’ and 打(dǎ)call ‘to root or cheer for someone’. I have referred to such expressions as semi-loan neologisms.

These neologisms are linguistically interesting in that although they involve elements from two languages on a lexical level, they are neither like regular loanwords nor like typical code-switching (though a bit like both phenomena in a broad sense). And since they are emerging in increasing numbers and becoming increasingly influential, they may well be a sign of some ongoing “mutation” both in the Chinese language and in Internet-era human language as a whole.

Hopefully this first post of mine in 2021 has been enjoyable. And Happy Niu Year to everyone again! 🐂😃

Leave a comment