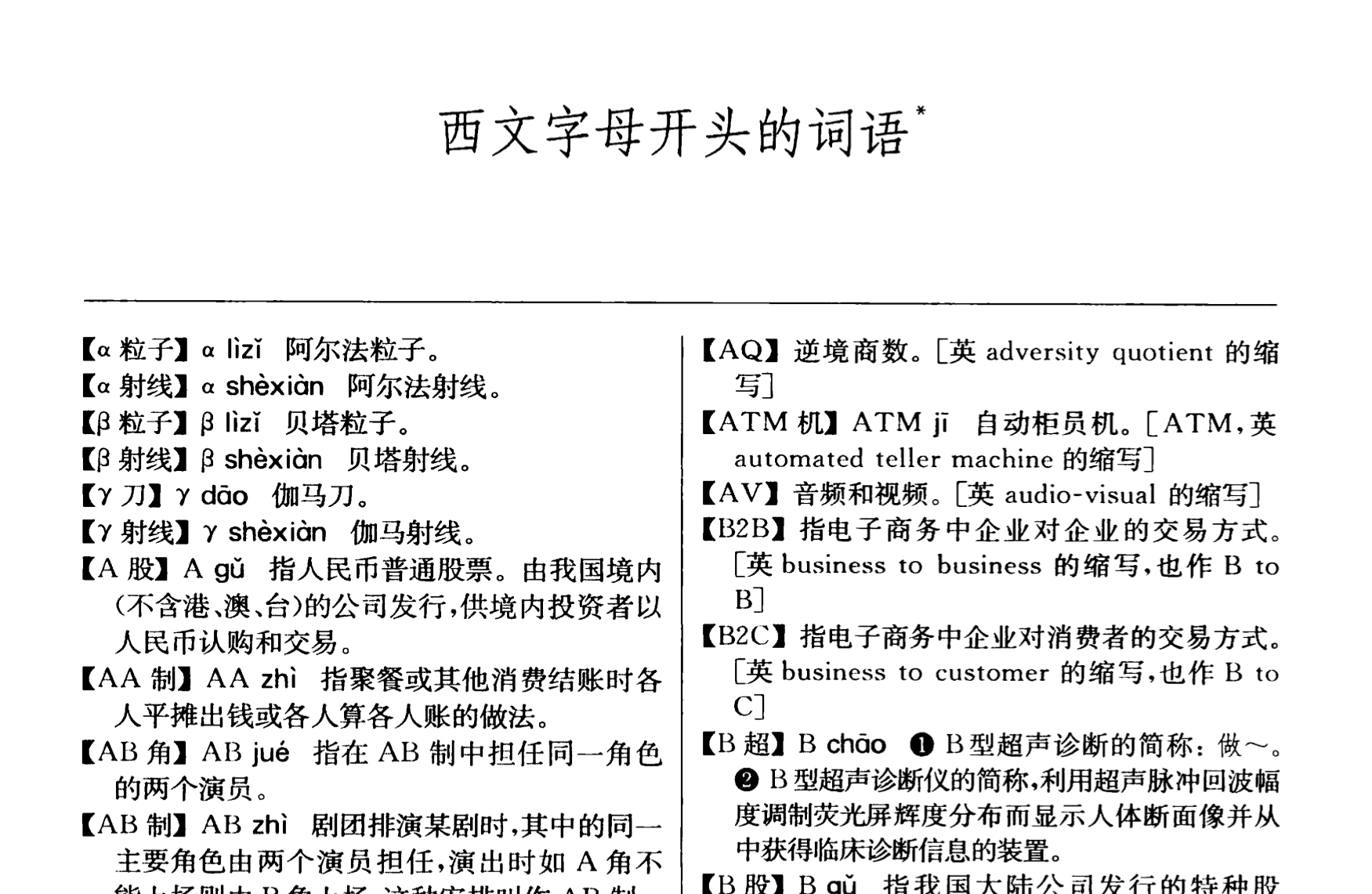

The sentence in the title of this post may sound awkward to an English speaker’s ears—How can one copy a filename extension to another?—but it turns out to be a perfectly grammatical utterance in Chinese (jump to the translation if you can’t wait), at least in the Chinese variety standardly spoken on the mainland, where “letter words” (字母詞) such as ppt and mp3 have become increasingly popular in recent years. In fact, they have gained so much momentum that a dedicated list of “words beginning with Western letters” has been added to the authoritative Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (現代漢語詞典) since its third edition (1996). And according to a survey conducted by the PRC State Language Commission in 2019, two out of the top ten Internet buzzwords in Mandarin Chinese in 2018 are letter words (skr and C位).

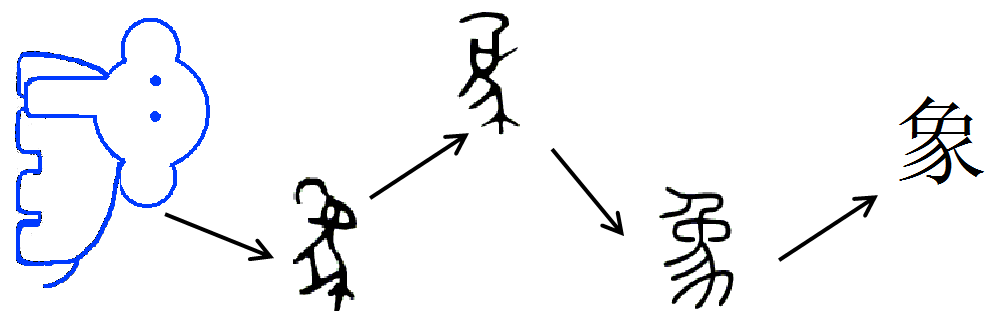

What makes letter words special in Chinese is exactly their alphabetic nature. As is well known, the Chinese writing system is not alphabetic but based on pictographic or phonosemantic logograms (aka Chinese characters). As such, letter words are in a sense “intruders” in Chinese texts.

Letter words vs. loanwords

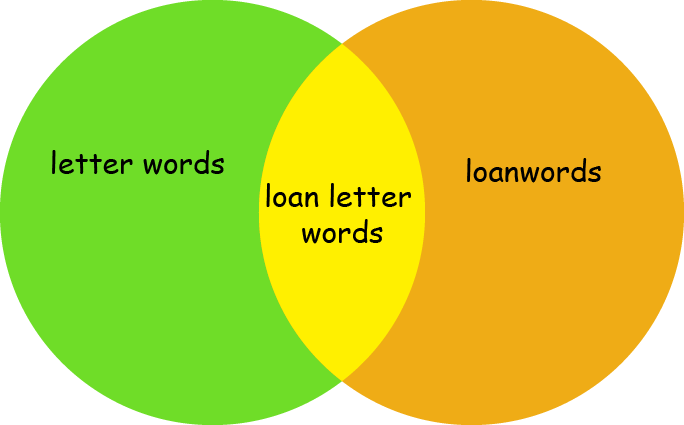

Letter words are not necessarily loanwords (though many of them are). A loanword is a word that is adopted from one language and incorporated into another without translation, such as English café (French-origin) and kindergarten (German-origin). Loanwords in Chinese are usually assigned dedicated characters based on their sounds, such as 沙發 sha1fa1 ‘sofa’ and 巧克力 qiao3ke4li4 ‘chocolate’. The technical term for this methodology is jia3jie4 (假借) or rebus, which is one of the oldest principles of character formation in the language.

Letter words, on the other hand, are simply written in letters. The majority of them are abbreviations based on the latin alphabet and pronounced in the English way; for example, the alphabetic part of the letter word ATM機 ‘ATM machine’ is just read as [ˌeɪˌtʰiːˈɛm] (or [eɪ˥-tʰiː˥-aɛ˧˥-m(ɯ)] if you wanna sound “native”). That being said, many letter words in Chinese actually don’t exist in English (or other languages using the latin alphabet) but are coined by Chinese speakers themselves, so an average English speaker wouldn’t be able to understand them at once. Some well-known examples of this kind are AA制 ‘to go Dutch’ (allegedly from algebraic average), HSK ‘Chinese Proficiency Test’ (= Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi 漢語水平考試), and CCTV ‘China Central Television’ (not closed-circuit television). Interestingly, from AA制 there have been derived two new terms AO制 and AB制. Can you figure out what they mean?🤓 See this page for an explanation.

In sum, letter words are a separate category from loanwords in Chinese. The two categories partly overlap but aren’t the same.

So, which category do the two abbreviations in the title (i.e., ppt and mp3) go into? We may call them “loan letter words,” though their meanings in Chinese differ a bit from their original meanings in English. In Chinese, they mean the following:

- ppt: (1) any presentation file, including but not limited to files produced by MS PowerPoint; (2) a single slide in a presentation.

- mp3: (1) an MP3 player; (2) any music file, including but not limited to files with an

.mp3extension.

Thus, what a Chinese speaker really means by the sentence in the title of this post is “Can I copy your presentation file onto my MP3 player (which I use as a handy data storage device)?” And believe me, this is not a rare request at all—back in high school I used to use my MP3 player as a USB flash disk all the time!

Semantic shift in loan letter words

Now I’ll go a bit deeper into the usage of ppt and mp3 in Chinese. In everyday contexts one may happily refer to a presentation as “a ppt” (1個ppt) even when it clearly has a .pdf or .keynote extension, and a single slide in a presentation is simply called “one page (of) ppt” (1頁ppt). Here the two senses of ppt are solely distinguished by their classifiers (i.e., measure words); namely, the generic 個 ge4 (for anything countable) and the more specific 頁 ye4 (for pages).

Similarly, the two senses of mp3 are also distinguished by their classifiers in daily usage. Compare the two sentences below for example:

- 昨天我買了一個mp3.

transcriptionwo3 zuo2tian1 mai3le yi2 ge4 mp3

verbatim glossI yesterday bought one <classifier> mp3

free translation“I bought an MP3 player yesterday.”

(the classifier is 個 ge4) - 我給你下了幾首mp3.

wo3 gei3 ni3 xia4le ji3 shou3 mp3

I for you downloaded several <classifier> mp3

“I downloaded a few music files (e.g., songs) for you.”

(the classifier is 首 shou3, for songs and poems)

It is not uncommon for loanwords to acquire new meanings in the target language, which is just semantic shift over time (a type of language change)—more specifically semantic widening or generalization in our cases at hand. This is a regular phenomenon in world languages regardless of etymology. For example, hoover originally only referred to a particular brand of vacuum cleaner but has now come to mean any type of vacuum cleaner. Loanwords are no exception to semantic shift, for once a foreign word is imported, it becomes part of the receiving language and can be normally targeted by linguistic rules in the language. Thus, while the plural form of Kindergarten in German is Kindergärten, it is kindergartens in English, following the English rule.

As such, the fact that ppt and mp3 have undergone Chinese-specific semantic shift (i.e., a shift unavailable in English) is also no surprise. Moreover, it is evidence that they have been “deforeignized” and truly become part of the Chinese lexicon (despite their alphabetic appearance). I guess they wouldn’t cause trouble if they’re fully localized (i.e., written in Chinese characters) either, though no one bothers completing this last step in an era where most educated citizens (especially netizens) have English as their second language since elementary school.

For the remaining part of this article see my next post.

Leave a comment