So, after reading many textbooks, watching many video tutorials, and attending two guided courses, I finally understood adjunction. That was a real “Eureka!” moment for me. One reason why I had invested so much time and energy in adjunction was because it played a vital role in my dissertation. If I didn’t properly understand the concept myself, how could I hope to use it to solve my linguistic problem?

Actually it feels a bit strange now that I’m “in the future,” because I can’t help wondering, How could it have taken me so long to understand such an obvious concept? But again, I guess that’s true for pretty much everything… I don’t know how to drive, but perhaps one day when I finally overcome my fear for traffic I’d also wonder “How could I not know how to drive?”

Adjunction is a weak functorial connection

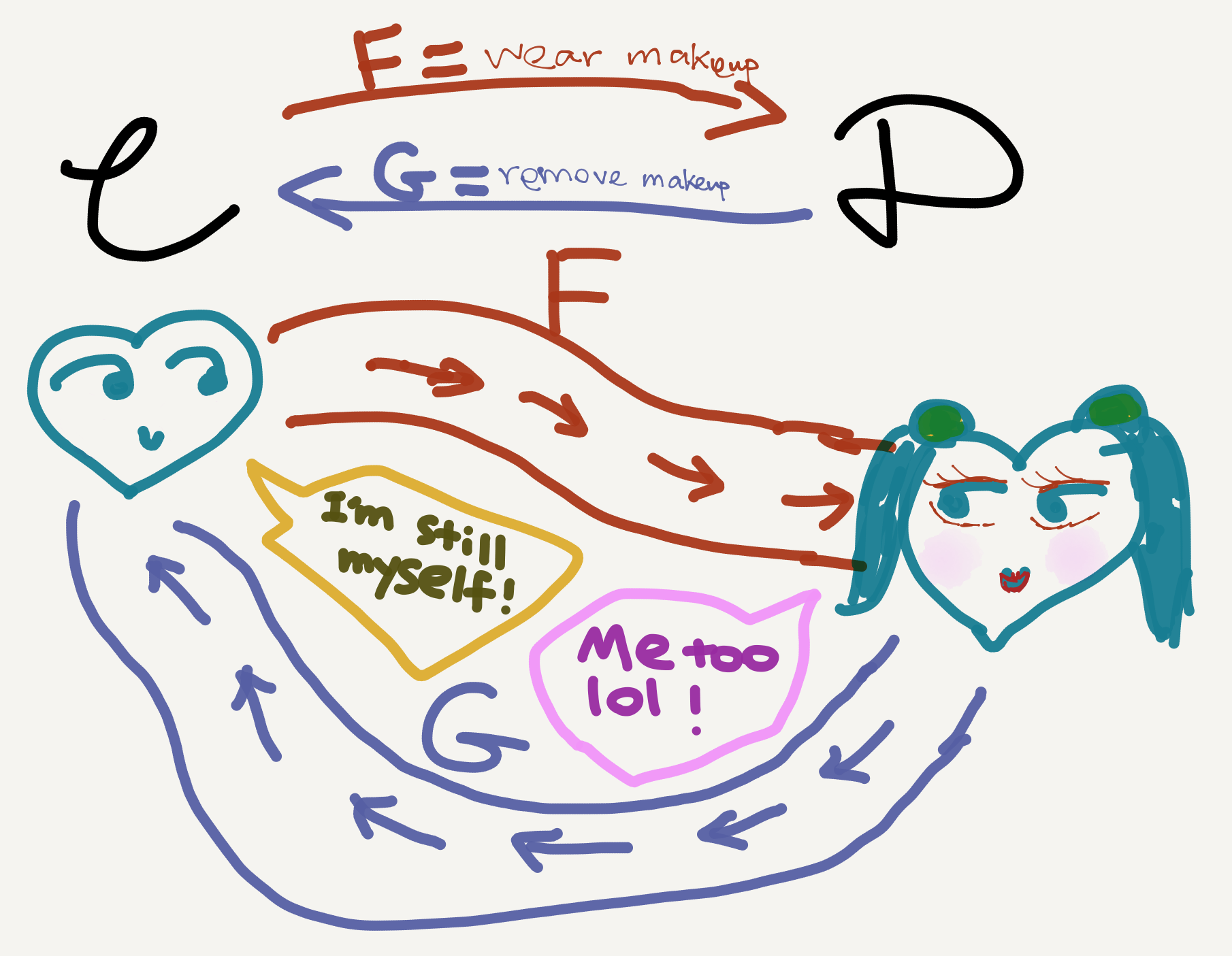

Now that I’m past the learning curve, let me try to explain adjunction in an intuitive fashion. An adjunction or adjoint situation describes a weak connection between two categories via functors. But since weak is a relative concept, let’s first ask what a strong connection is.

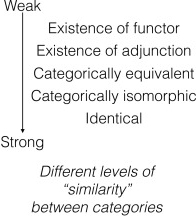

Given two categories, what’s the strongest level of similarity they can enjoy? An isomorphism. Indeed, in category theory if two categories are isomorphic to each other, then they can be treated as the same in all aspects that matter. Remember that a categorical isomorphism is defined as a two-sided or full inverse (see my Sep 5 post): given two categories $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{D},$ they are isomorphic iff there exist functors $F\colon\mathbb{C}\rightarrow\mathbb{D}$ and $G\colon\mathbb{D}\rightarrow\mathbb{C}$ such that $G\circ F=1_\mathbb{C}$ and $F\circ G=1_\mathbb{D}.$

In other words, if two categories are isomorphic, then any object in either of them would return to itself following a functorial round trip. For example, if $C$ is in $\mathbb{C},$ then $G(F(C))=C.$

If the functorial round trips send arguments (aka objects) back to themselves, the two categories have the strongest level of similarity. But what if the round trips don’t send arguments back to themselves? There are three further possibilities:

- If the arguments are sent back to somewhere isomorphic to themselves, the two categories have a second-best similarity, called an equivalence of categories.

- If the arguments are not sent back to their isomorphic partner but merely to somewhere related to themselves in a particular way (i.e., that defining an adjunction), the two categories have a weak similarity.

- If the arguments are not even sent back to their adjoint round-trip partners, then the two categories have no similarity. In other words, they are just two randomly paired categories with two randomly picked functors. 😂

More elaborately, Tsuchiya, Taguchi & Saigo propose five levels of similarity between categories in their 2016 paper “Using category theory to assess the relationship between consciousness and integrated information theory.”

Source: Tsuchiya, Taguchi & Saigo (2016, p. 2)

I didn’t mention “identical” above because it’s rarely useful in category theory; or rather, category theory is rarely used for scenarios where things can be checked for identicality—set theory would be more useful in such scenarios. But anyway, Tsuchiya et al.’s classification is more complete.🙂

So, an adjunction is a special form of similarity between categories that is only stronger than the lack of similarity.

From round trip to (co-)unit

There are several ways to define an adjunction. In this post I only discuss two of them: one based on two special natural transformations, called the unit ($\eta$) and the co-unit ($\varepsilon$), and the other based on a special isomorphic natural transformation or natural isomorphism ($\theta$). Since the (co-)unit-based perspective is closely related to the round-trip method, I’ll start with it.

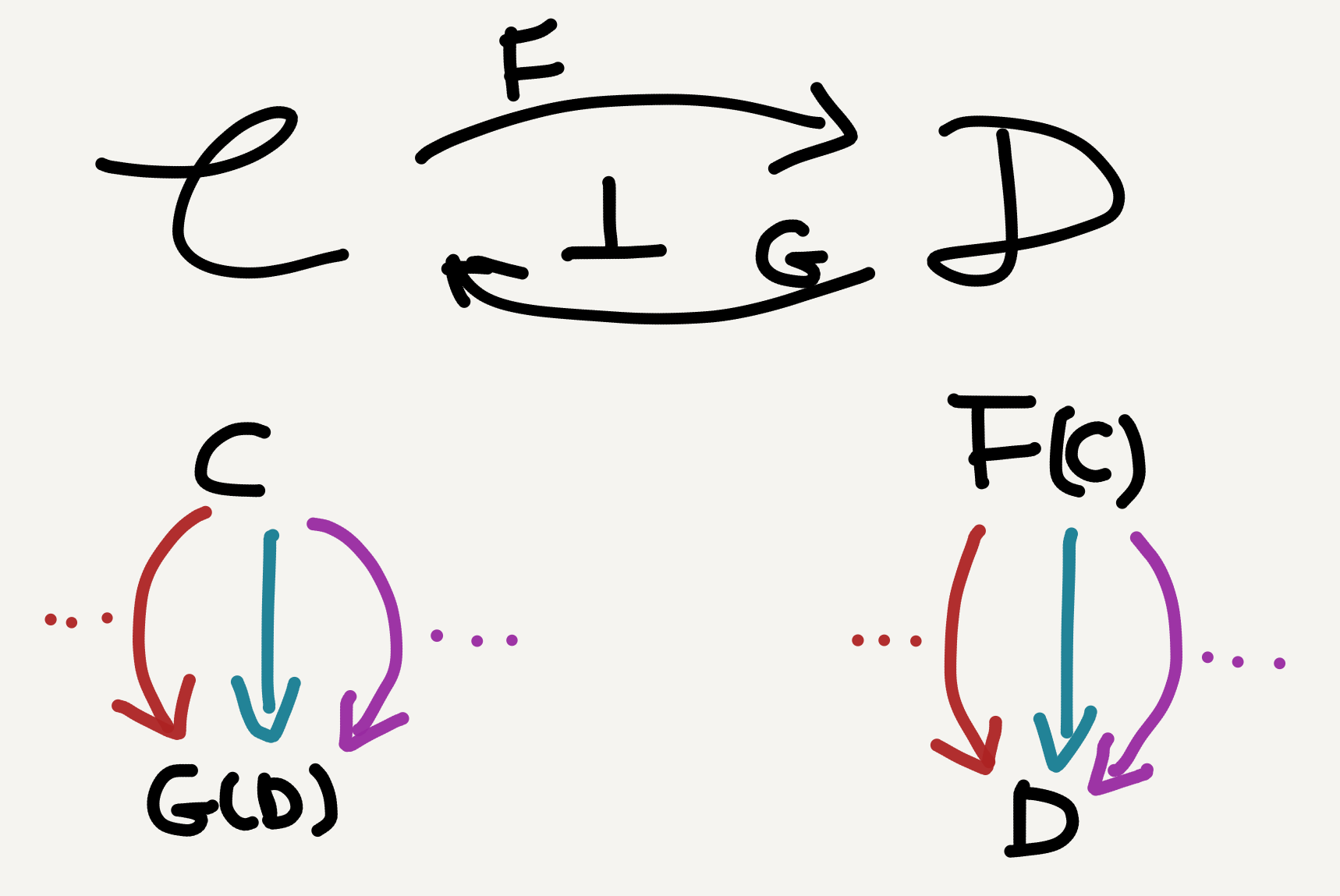

As above-mentioned, “adjunction” is the name for a special kind of functorial connection between two categories. It’s special in that given two categories $\mathbb{C}, \mathbb{D}$ and two functors $F, G,$ for any $C$ in $\mathbb{C}$ and any $D$ in $\mathbb{D}$ the following arrows uniquely determine each other: \[ f\colon F(C)\rightarrow D\; \text{and}\; g\colon C\rightarrow G(D). \] That is, for each $\mathbb{D}$-arrow $F(C)\rightarrow D$ there’s a uniquely matching $\mathbb{C}$-arrow $C\rightarrow G(D),$ and vice versa.

You may wonder, Why these arrows with these source/target objects instead others? I had also been puzzled by this question, but later I realized that the so-called adjoint situation is really just a particular pattern spotted by mathematicians in their research. Perhaps the motivating examples are more informative as to why the above arrows are at issue, but as nonmathematician beginners we don’t really have the background knowledge to understand or the interest to care about those examples, especially if we just want to quickly learn abstract category theory and apply it to our own work. So I eventually settled for the following line of thought:

- Yes, the special arrows in an adjunction look contrived and out-of-nowhere. ==>

- But that’s because they’re indeed contrived and out-of-nowhere in an ordinary person’s eyes, like many other mathematical constructs. ==>

- So just accept it and learn to appreciate this contrived and out-of-nowhere yet beautiful mathematical pattern.

Back to our given configuration, since $C$ and $D$ are chosen randomly in $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{D}$—namely, any objects in the two categories would work—we are free to choose particular $C$s and $D$s and pass them into the matching arrows. The “clever” objects to choose here are $C := G(D)$ or $D := F(C)$—again these choices are not a priori but based on mathematicians’ practical experience (which are left out in textbooks for obvious pedagogical reasons).

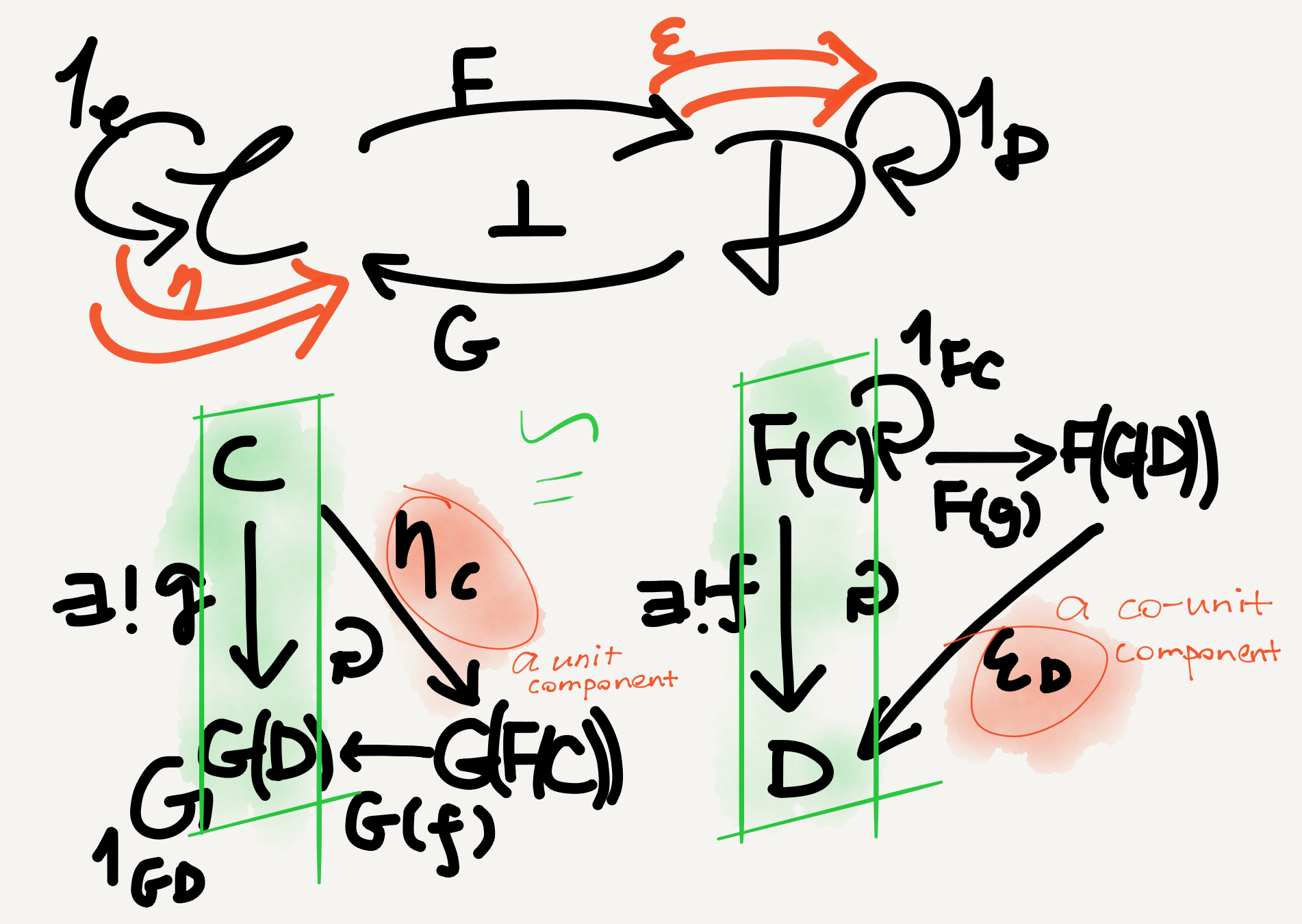

- If we let $C$ be $G(D),$ the matching arrows become $F(G(D))\rightarrow D$ and $G(D)\rightarrow G(D).$ Now these look familiar: the former is just a functorial round trip applied to $D$ and the latter just the identity arrow on $G(D)$! Since $D$ can freely vary in $\mathbb{D},$ we in effect get a natural transformation $F\circ G\Rightarrow 1_\mathbb{D},$ which is called the co-unit of the adjunction and usually denoted by $\varepsilon.$

- Similarly, if we let $D$ be $F(C),$ the matching arrows become $F(C)\rightarrow F(C)$ and $C\rightarrow G(F(C)).$ These are again an identity arrow and a functorial round trip (this time applied to $C$). And since $C$ can freely vary in $\mathbb{C}$ we get another natural transformation $1_\mathbb{C}\Rightarrow G\circ F,$ called the unit of the adjunction and denoted by $\eta.$

Mnemonic: To remember which natural transformation is the unit and which is the co-unit I came up with a one-word mnemonic “coin,” which means “the co-unit goes in (the identity natural transformation).”

I illustrate the above two “contrived yet beautiful” scenarios below:

The co-unit and the unit are both natural transformations between endofunctors (i.e., functors from a category to itself): the unit is associated with $\mathbb{C}$ and the co-unit with $\mathbb{D}.$ This makes them not only useful for the definition of adjunction but also useful for that of monad, though I won’t go into that topic here.

To sum up this section, an adjunction can be defined as a quadruple $\langle F, G, \eta, \varepsilon\rangle$—because the uniquely matching arrows above can be expressed in terms of these data. The adjunction thus obtained is conventionally notated by a shorthand $F \dashv G,$ where $F$ is called the left adjoint and $G$ the right adjoint. N.b. here left and right are not associated with any deeper meanings but merely reflect the surface syntax of the notation $F \dashv G.$ See my Sep 5 post for more comment (aka grumbling😅) on the various left/right terms in category theory.

For the remaining part of this article see my next post “Category theory notes 13: Adjunction (Part 2).”

Leave a comment