In the previous post “Category theory notes 12: Adjunction (Part 1)” I wrote about my thoughts on adjunction, an extremely important component of category theory. In particular, I identified an adjunction as a weak functorial connection between two categories and illustrated its (co-)unit-based definition in a (hopefully) intuitive way. In this post I’ll go on to illustrate the natural-isomorphism-based definition for adjunction. Then I’ll try to explain the so-called triangular identities.

From unique matching to natural isomorphism

Another way to define the adjunction $F \dashv G$ is to forget about the (co-)unit and merely focus on the uniquely matching arrows, which determines a one-to-one correspondence between two hom-sets—for each arrow between $F(C)$ and $D$ (i.e., each element in the hom-set $\mathbb{D}(F(C),D)$) there’s a matching arrow between $C$ and $G(D)$ (i.e., an element in the hom-set $\mathbb{C}(C,G(D))$).

Since $C$ and $D$ can freely vary in $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{D},$ we can replace $C, D$ by two placeholders $-$ and $=$; namely, $F(-)\rightarrow(=)$ and $(-)\rightarrow G(=).$ N.b. these placeholders are randomly chosen. You can use any placeholder you like (some people don’t even distinguish the two and merely use a single $-$ as a “wildcard”). It’s a trivial issue but can be very confusing if not properly clarified (I for one struggled with it!).

Thus, as long as we provide two concrete “arguments” to fill the two placeholders, we can get two concrete arrows as “values.” The two arguments respectively come from $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{D},$ and the values are elements of two particular sets (i.e., the respective hom-sets). Therefore, the two matching arrows extend to two functors from the product category $\mathbb{C}\times\mathbb{D}$ to the category $\mathbf{Set}$ (these are called bifunctors), and the one-to-one mappings (i.e., bijections) between the arrows extend to an isomorphic natural transformation, or natural isomorphism, between the two bifunctors, which is usually denoted by $\theta$. Well, actually for arrow-composition reasons (to be illustrated shortly) $\mathbb{C}$ is replaced by its opposite category $\mathbb{C}^{op}$ in the bifunctors, so we have \[ \mathbb{D}(F(-), =), \mathbb{C}(-, G(=))\colon \mathbb{C}^{op}\times\mathbb{D} \rightarrow \mathbf{Set} \] instead, where $\mathbb{D}(F(-), =)$ means the hom-set between $F(-)$ and $(=)$ in $\mathbb{D},$ and accordingly \[ \theta\colon \mathbb{D}(F(-),=) \xrightarrow{\cong} \mathbb{C}(-,G(=)), \] where the symbol $\xrightarrow{\cong}$ denotes a natural isomorphism. Since the natural isomorphism well describes the adjoint situation, the adjunction can be defined via it as a triple $\langle F, G, \theta\rangle$.

Some people also use the above natural isomorphism syntax to memorize which is the left adjoint and which is the right adjoint: $F$ is the left adjoint because it’s literally on the left. However, since the left/right allocation has no deep meanings as I mentioned, you can feel free to choose other or even invent your own mnemonics.😼

Why $op$?

Now I turn to explain why the first component of the product category needs to be an opposite category. It’s usually only mentioned in passing in textbooks and video tutorials, sometimes without any explanation and sometimes with a note like “it’s each to check” or “find out why by yourself.” And that can be VERY confusing. The op-trick is skill-demanding and not obvious for newbies at all, so I don’t understand why textbooks are so stingy with a clearer explanation. 🙄

Anyway, here’s the trick, which I managed to understand after carefully reading many resources. First, we should realize that whether we choose to use the original $\mathbb{C}$ or the opposite $\mathbb{C}^{op}$ doesn’t affect our choice of arguments for the bifunctors, because $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{C}^{op}$ have exactly the same objects—a $C$ in $\mathbb{C}$ is also a $C$ in $\mathbb{C}^{op}.$ What the op-trick does affect is how arrows are mapped, because an arrow in $\mathbb{C}^{op}$ is opposite in direction to the corresponding arrow in $\mathbb{C},$ like this:

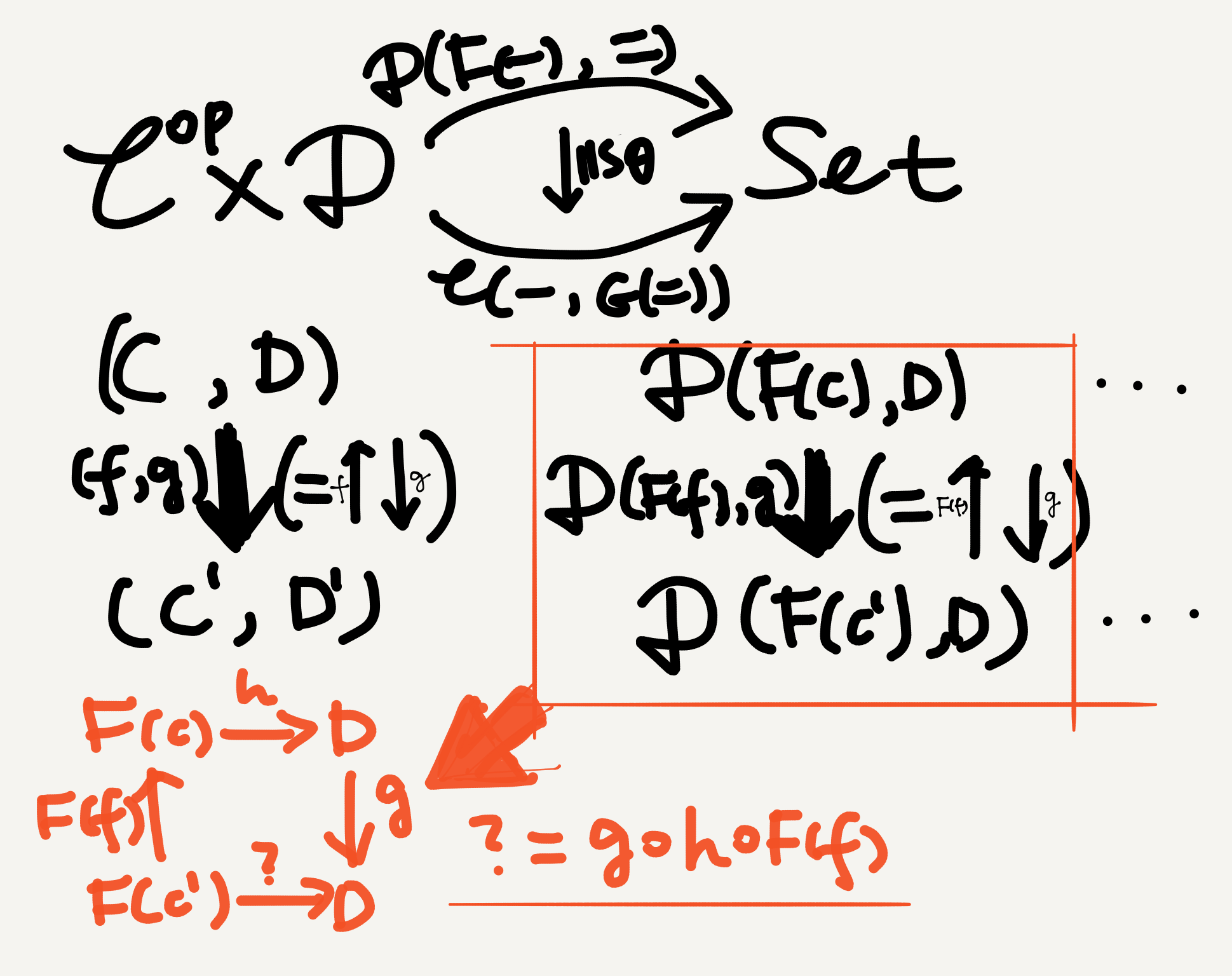

And this is exactly the trick we need, because of the configuration below:

As we can see from the picture, since the two bifunctors map pairs of objects to hom-sets, and hom-sets have arrows as elements, the $\mathbf{Set}$-arrow $\mathbb{D}(F(C),D)\rightarrow\mathbb{D}(F(C’),D’)$ is really a square (i.e., the orange one). Since the functoriality of $\mathbb{D}(F(-),=)$ requires that there must be a corresponding $\mathbf{Set}$-arrow $\mathbb{D}(F(C),D)\rightarrow\mathbb{D}(F(C’),D’)$ when there exists a $\mathbb{C}^{(op)}\times\mathbb{D}$-arrow $(C,D)\rightarrow(C’,D’),$1 when the latter exists, its functorial “lifting” to the former must be able to map each element in $\mathbb{D}(F(C),D)$ to an element in $\mathbb{D}(F(C’),D’).$

In other words, given an element $h\in\mathbb{D}(F(C),D),$ we must be able to express an element in $\mathbb{D}(F(C’),D’)$ in terms of $h$ and $\mathbb{D}(F(f),g).$ The orange square in the above picture clearly shows that there’s only one way to achieve this—via an upward arrow $F(f)$ and a downward arrow $g,$ whereby the unknown arrow $?=g\circ h\circ F(f).$ This is why we need an arrow pointing from $C’$ to $C$ to begin with and hence why we need the first component of the product category to be $\mathbb{C}^{op}$.

Of course, we can also let the product category remain $\mathbb{C}\times\mathbb{D}$ and do a trick to the bifunctors instead. In that case the bifunctors need to be contravariant in their first component and covariant in their second component. Thus, $f\colon C\rightarrow C’$ becomes $F(f)\colon F(C’)\rightarrow F(C)$ while $g$ doesn’t change direction, and we obtain the orange square again.

In short, we need $\mathbb{C}^{op}$ because functors must lift arrows and the target objects (i.e., hom-sets) themselves are sets of arrows.

A note on the term contravariant: it can sometimes be confusing for beginners (especially if you like rational terminology like me) because some people use it to mean either a truly contravariant functor like this

or a de facto covariant functor with an opposite category as its source like this

I personally prefer only calling truly contravariant functors “contravariant,” because if a functor is covariant, it doesn’t make much sense to call it contravariant, at least linguistically. If we really need a term for the “covariantly presented contravariant functor,” so to speak, I prefer describing the entire configuration as a contravariant situation.

Triangular identities

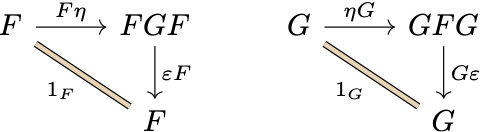

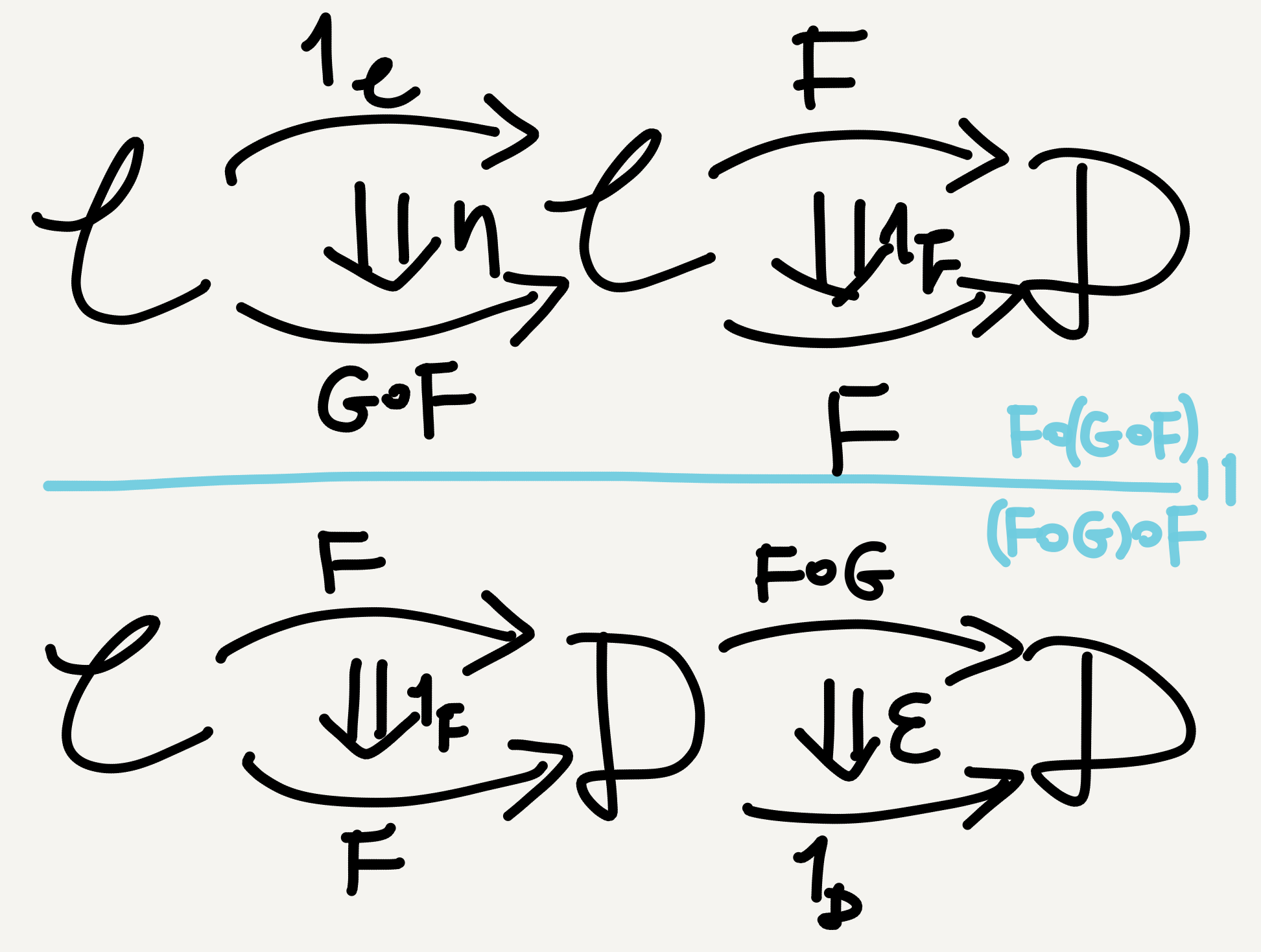

A last difficult point in the abstract theory of adjunction I’d like to comment on is a pair of natural-transformation-based equations, the triangular identities. Given an adjunction $\mathbb{C}\colon F \dashv G\colon\mathbb{D}$ with unit $\eta$ and co-unit $\varepsilon,$ the following equations hold: \[ \varepsilon F \circ F\eta = 1_F, \] \[ G\varepsilon \circ \eta G = 1_G. \] Diagrammatically

My first reaction on seeing these was “What the heck?! 🥴🙀…” In hindsight, a large part of my confusion was caused by the notation—in particular the horribly unreasonable convention to denote an identity natural transformation on a functor by the symbol for the functor itself (e.g., $F$ is either a functor or a natural transformation). On this point I highly agree with Harold Simmons:

You will also find in the literature that some people write $A$ for the arrow $id_A.$ This is a notation so ridiculous that it should be laughed at in the street. (Simmons 2011, An Introduction to Category Theory, p. 3)

After a more rational change of notation, with all the ambiguous symbols disambiguated and all the omitted composition circles filled back, things become a lot easier to understand:

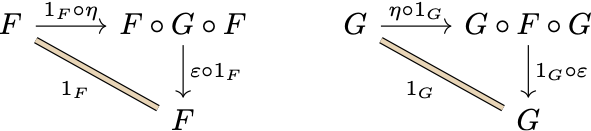

I name these prettified triangular identities. 🙃 After the prettification, it’s now clear that each triangle involves two steps of horizontal natural transformation composition. For example, in the left-hand triangle the composite natural transformation $1_F\circ\eta$ maps the functor $F$ to the functor $F\circ G\circ F,$ both of which go from $\mathbb{C}$ to $\mathbb{D},$ while the other composite natural transformation $\varepsilon\circ 1_F$ maps $F\circ G\circ F$ back to $F.$ As I illustrate below, the two mapping steps are enabled by the associativity and unitality of functor composition: (i) (associativity) $F\circ (G\circ F)=(F\circ G)\circ F$; (ii) (unitality) $F\circ 1_\mathbb{C} = 1_\mathbb{D}\circ F = F.$

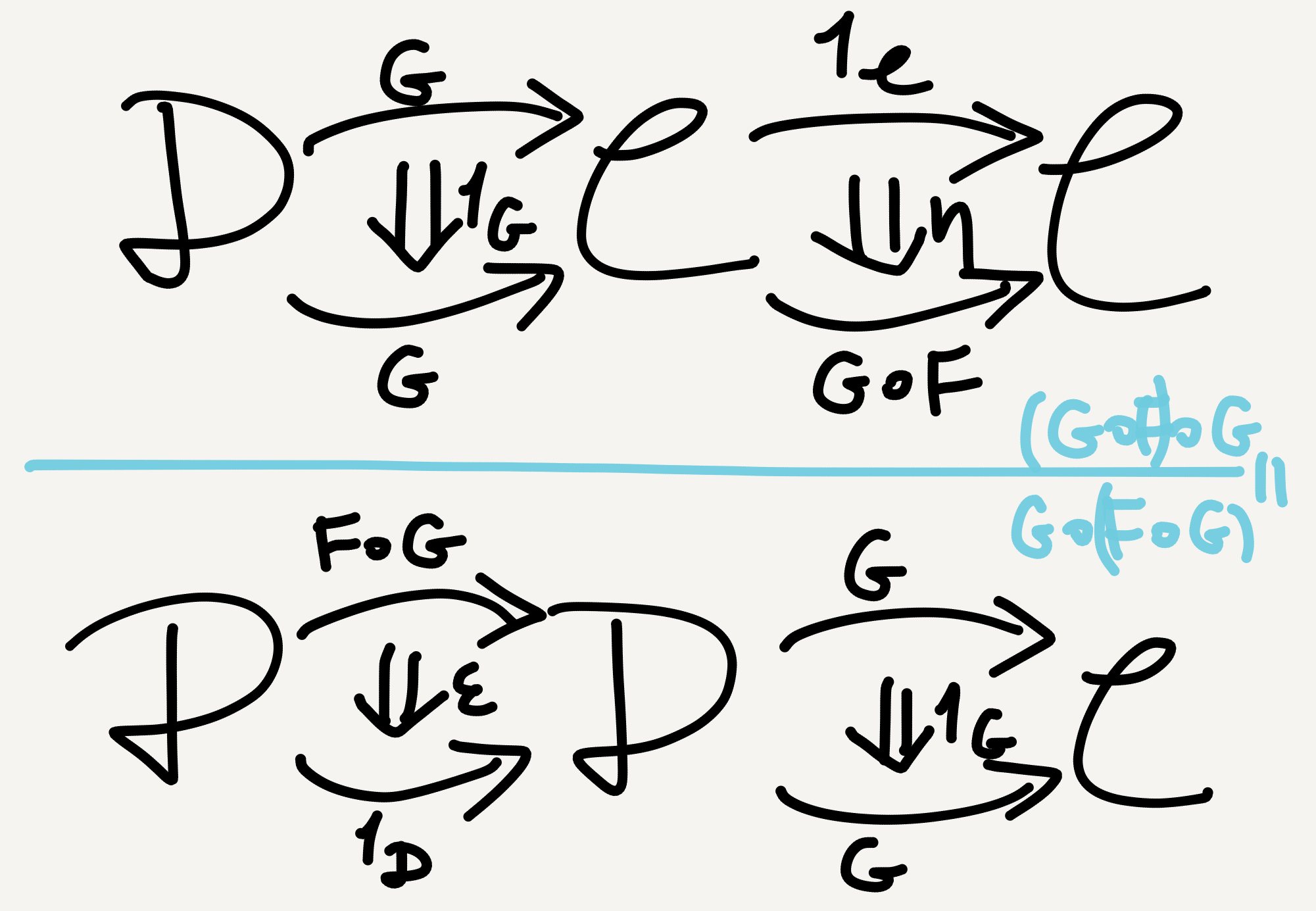

The right-hand triangle can be understood similarly, also by the associativity \[ (G\circ F)\circ G = G\circ(F\circ G) \] and unitality \[ 1_\mathbb{C}\circ G = G\circ 1_\mathbb{D} = G \] of functor composition, as illustrated below.

The triangular identities can also be understood via composition in 2-category or “whiskering.” However, for beginners I think the above-illustrated “verbose” approach is the easiest to follow.

Takeaway

- There are several graded levels of similarity between categories, among which adjunction is a relatively weak one.

- An adjunction can be defined either via (co-)unit, under the round-trip-based perspective, or via a special natural isomorphism, under the arrow-matching-based perspective.

- The triangular identities arising from an adjunction are formulated in terms of (co-)unit and horizontal composition and can be understood via the associativity and unitality of functor composition.

Leave a comment