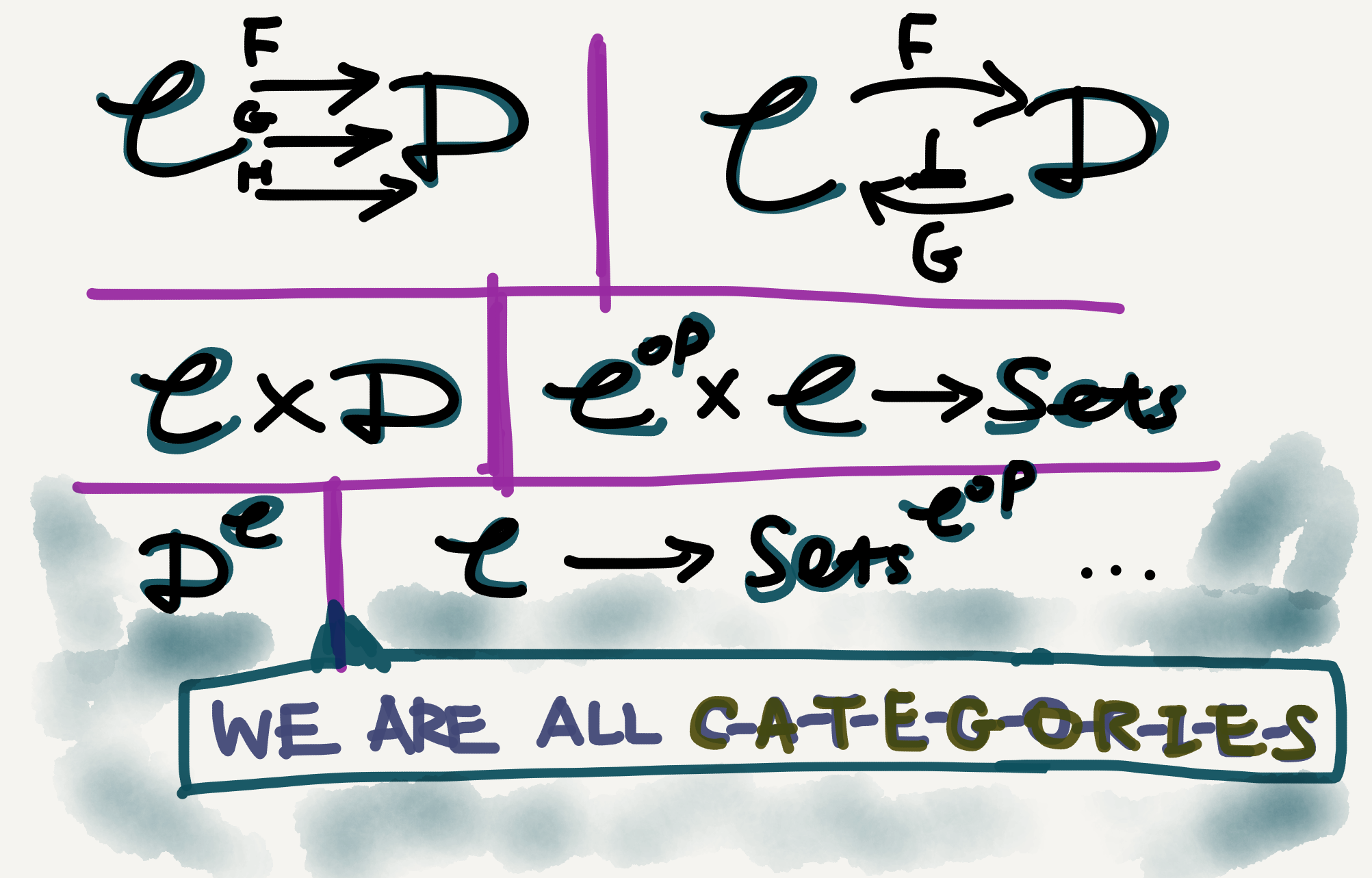

So far in this series I’ve viewed a category as an individual and independent entity. Two categories may be related by functors or even better connected by an adjunction; they may together construct some new type of category (such as a product category or a functor category); and they may be viewed as objects in a larger ambient category $\mathbf{Cat}.$ But in all these situations each category, however complex or simple, is just a category. So to speak, they all have equal “morphological status.”

Subcategory in linguistics and in mathematics

But we linguisticians know well that category is not a lonely word—it has morphological relatives like subcategory, supercategory, and so on. Incidentally, in category theory there’s also a notion subcategory, whose meaning (surprisingly) isn’t too different from linguistic subcategories, at least in practice.

Both mathematical and linguistic subcategories seem to be restrictions of bigger categories. Thus, in linguistics we say a transitive verb is a subcategory of verb, a mass noun is a subcategory of noun, etc. Similarly, mathematicians say the category of finite sets is a subcategory of the category of sets, the category of abelian groups is a subcategory of the category of groups, etc.

However, the definition of “subcategory” is quite different in linguistics and in mathematics, and it’s surprising that in spite of this definitional difference the “subcategory”-based sentences above all read perfectly well and are intuitively close in semantics (which is an illusion, of course!).

In most branches of linguistics (well, except categorial grammars) categories are defined by their internal properties (called features) and so a subcategory is just defined as a category that inherits its parent category’s features (this method is most saliently reflected in HPSG). Thus, a transitive verb has all the features that a verb has but in addition has the extra feature(s) defining (linguistic) transitivity.

By comparison, mathematical subcategories aren’t defined by feature inheritance but are defined by “data inheritance,” if I may put it this way. The data of a category are just its objects and arrows (together with the relevant laws), so data inheritance just means the cross-category inheritance of objects and/or arrows. The following quote is from Wikipedia:

A subcategory of a category $\mathbb{C}$ is a category $\mathbb{S}$ whose objects are objects in $\mathbb{C}$ and whose morphisms are morphisms in $\mathbb{C}$ with the same identities and composition of morphisms. Intuitively, a subcategory of $\mathbb{C}$ is a category obtained from $\mathbb{C}$ by “removing” some of its objects and arrows.

The above informal definition reveals an important difference between the linguistic and the mathematical definitions of “subcategory”: linguisticians define subcategories by adding data (i.e., extra features), whereas mathematicians define subcategories by removing data (i.e., existing objects/arrows). Is there any deeper connection between the two seemingly opposite strategies? I don’t know.🤷♂️

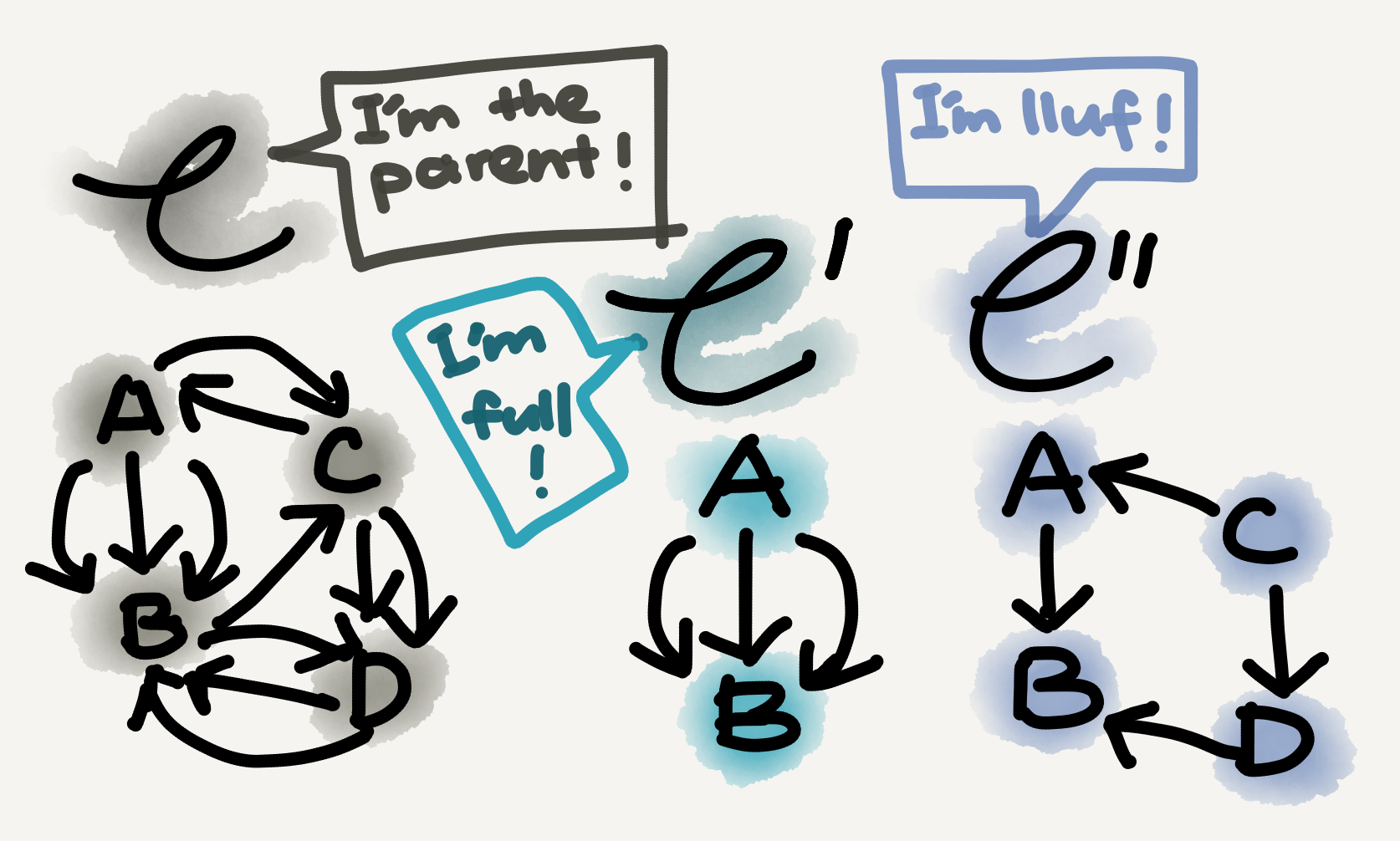

Full and lluf subcategories

Since there are two types of data in a category—object and arrow—when characterizing subcategories we can also talk about them separately. Usually a subcategory needn’t retain entire hom-sets from its parent category, but when it does it has a special name, a full subcategory.

Likewise, a subcategory needn’t retain all objects from its parent category either, but when it does it also has a special name, a lluf subcategory (aka wide subcategory). Notice that lluf is just full spelled backwards.

What’s a subcategory that’s both full and lluf? Well, that’s just the parent category itself…

A subcategory is related to its parent category via a special functor, called an inclusion functor (usually denoted by the letter i, either capital or small). It sends objects and arrows in the subcategory to themselves in the parent category. Since both mappings are one-to-one, an inclusion functor is automatically faithful and injective on objects (see my Sep 1 post for comments on these and other jectivity-related notions).

When the subcategory in question is also full, the inclusion functor is full as well (so it’s now fully faithful); when the subcategory is lluf, the inclusion functor is surjective on objects (so it’s now bijective on objects). With respect to the picture above, an inclusion functor from $\mathbb{C}’$ to $\mathbb{C}$ would be fully faithful, and an inclusion functor from $\mathbb{C}’’$ to $\mathbb{C}$ would be bijective on objects.

A fully faithful inclusion functor is obviously an embedding functor; however, not all embedding functors are inclusion functors. As an example recall from my Sep 12 post that the Yoneda Functor is an embedding, but it’s not an inclusion functor (for it doesn’t map things to themselves). In short, embedding is a more relaxed notion than (full) inclusion.

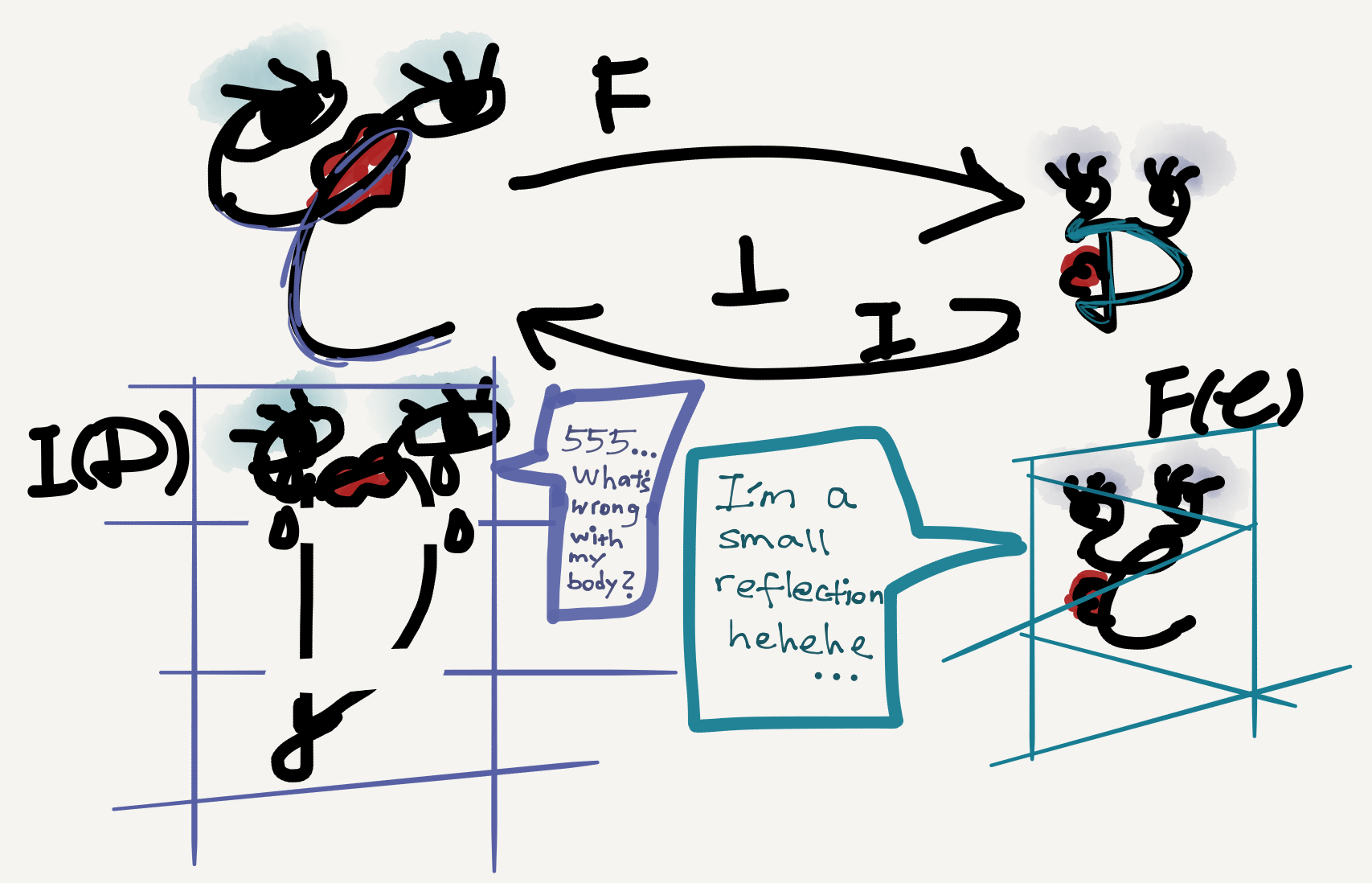

Reflective subcategory

In my Sep 8 post I wrote about adjunction. In fact there’s a particularly nice adjunction scenario characterized by a full subcategory, which is called a reflective subcategory. This notion provides a suitable mathematical tool to study situations where one domain (viewed as a category) sorts or partitions another domain (viewed as another category) into subparts. For example, I used it in my dissertation, where the two domains involved were ordered sets of grammatical categories (qua types). But since the categorical result is highly general, the two domains really can be anything provided they can be categorified.

As the picture shows, a reflective subcategory situation is an adjoint situation where the right adjoint is an inclusion functor (usually indicated by an arrow with a hooked tail). N.b. the subcategory in question should also be full.

A full subcategory $\mathbb{A}$ of a category $\mathbb{B}$ is said to be reflective in $\mathbb{B}$ when the inclusion functor from $\mathbb{A}$ to $\mathbb{B}$ has a left adjoint. This adjoint is sometimes called a reflector. (Wikipedia)

There’s nothing difficult in this definition. What I’d like to point out is that in practice the definition of reflective subcategory needn’t be so strict. In particular, a reflective subcategory needn’t necessarily be a strictly defined subcategory itself but may also just be isomorphic to one. Since in category theory isomorphic objects/categories are literally the same, we can safely identify a reflective subcategory and a category isomorphic to it.

For the remaining part of this article see my next post “Category theory notes 18: Reflective subcategory (Part 2).”

Leave a comment