Throughout this blog series I’ve been writing about category-theoretic results in their fully general forms, which are applicable to all categories from all domains. In a sense, this is the “true merit” of category theory, whose results are so abstract that their applicability is effectively “limitless” (mind the pun!). In this final article, however, I’d like to discuss the “instantiation” of category theory in a particular domain—the domain of posets. Below is the definition of a poset from Wikipedia:

A set with a partial order is called a partially ordered set (also called a poset).

A (non-strict) partial order is a binary relation $\le$ over a set $P$ satisfying [three] axioms … [which] state that the relation $\le$ is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive.

Posets are highly useful in applied category theory because many cross-disciplinary phenomena are underlyingly just ordered sets. Besides, posets (or more generally preorders) are a nice “short cut” to learn category theory. In Seven Sketches, for instance, Fong & Spivak first introduce category-theoretic results in the context of preorders (throughout the first two chapters!) before finally embarking on “canonical” category theory (in Chapter 3). In their words:

[I]t is a useful principle in studying category theory to try to understand concepts first in the setting of preorders – where often much of the complexity is stripped away and one can develop some intuition – before considering the general case. (p. 37)

Similarly, Awodey writes in the preface of Category Theory that

Many phenomena occurring in categories can best be understood as generalizations from posets or monoids. (p. x)

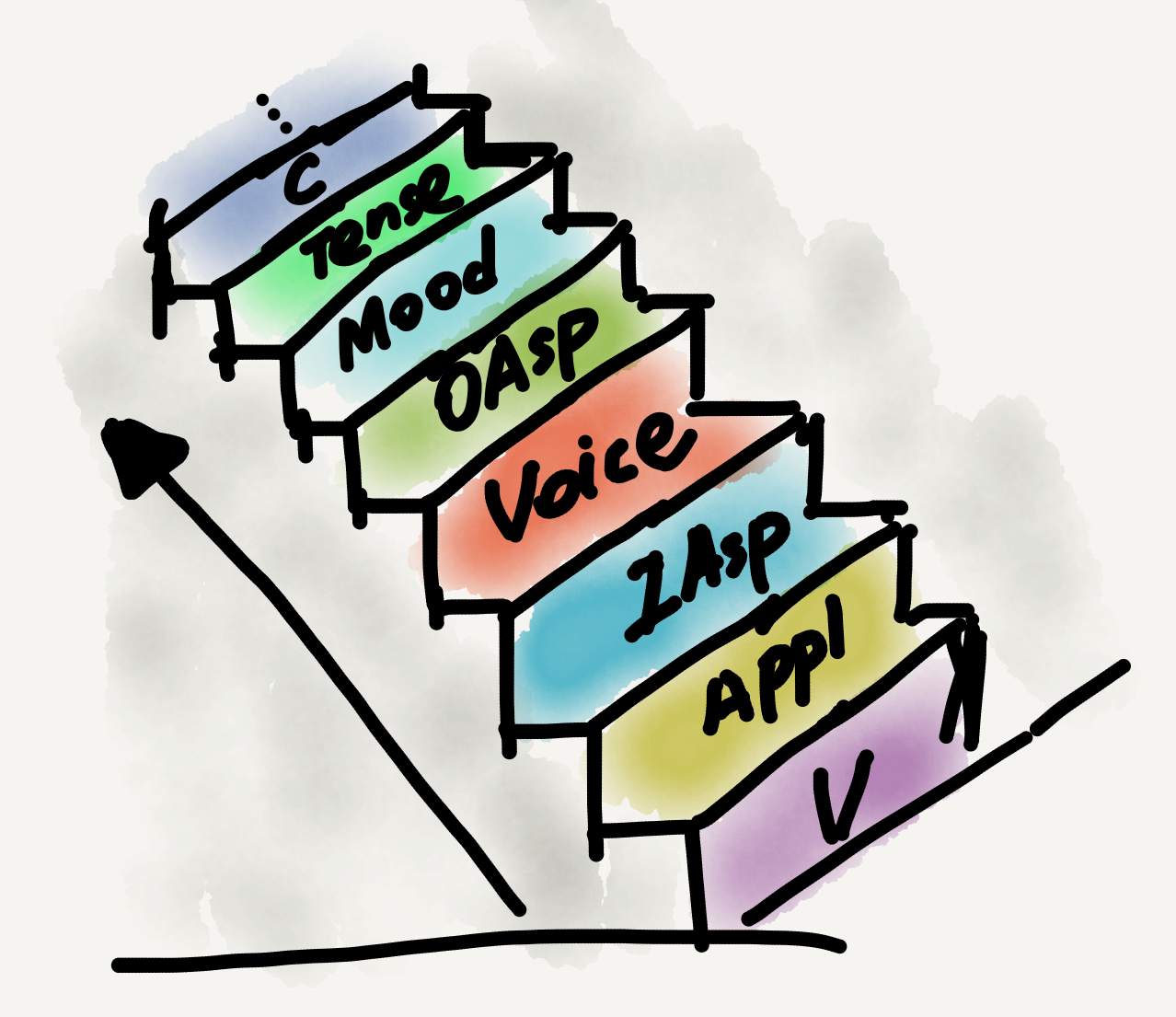

Echoing this state of affairs, my own application of category theory in my dissertation was also based on posets. Linguisticians have proposed numerous grammatical categories or types for natural languages, such as noun, verb, tense, aspect, determiner, classifier, and many more (there are dozens or even hundreds of them!). An important heuristic from linguistic research in the past decades is that grammatical categories aren’t randomly warehoused in the human mind but rather organized into hierarchies (called “hierarchies of projection” for theory-internal reasons).

In my dissertation I showed that grammatical category hierarchies are actually posets, and various hierarchies across world languages (there are many of them!) are all connected to one another via an epi-adjunction (see my Sep 14 post for the definition of this term). There are still other nice characteristics of human language grammatical category hierarchies revealed with the aid of category theory (I boldly refer you to my dissertation for those😜), but this epi-adjunction scenario is the most crucial one I’ve discovered.

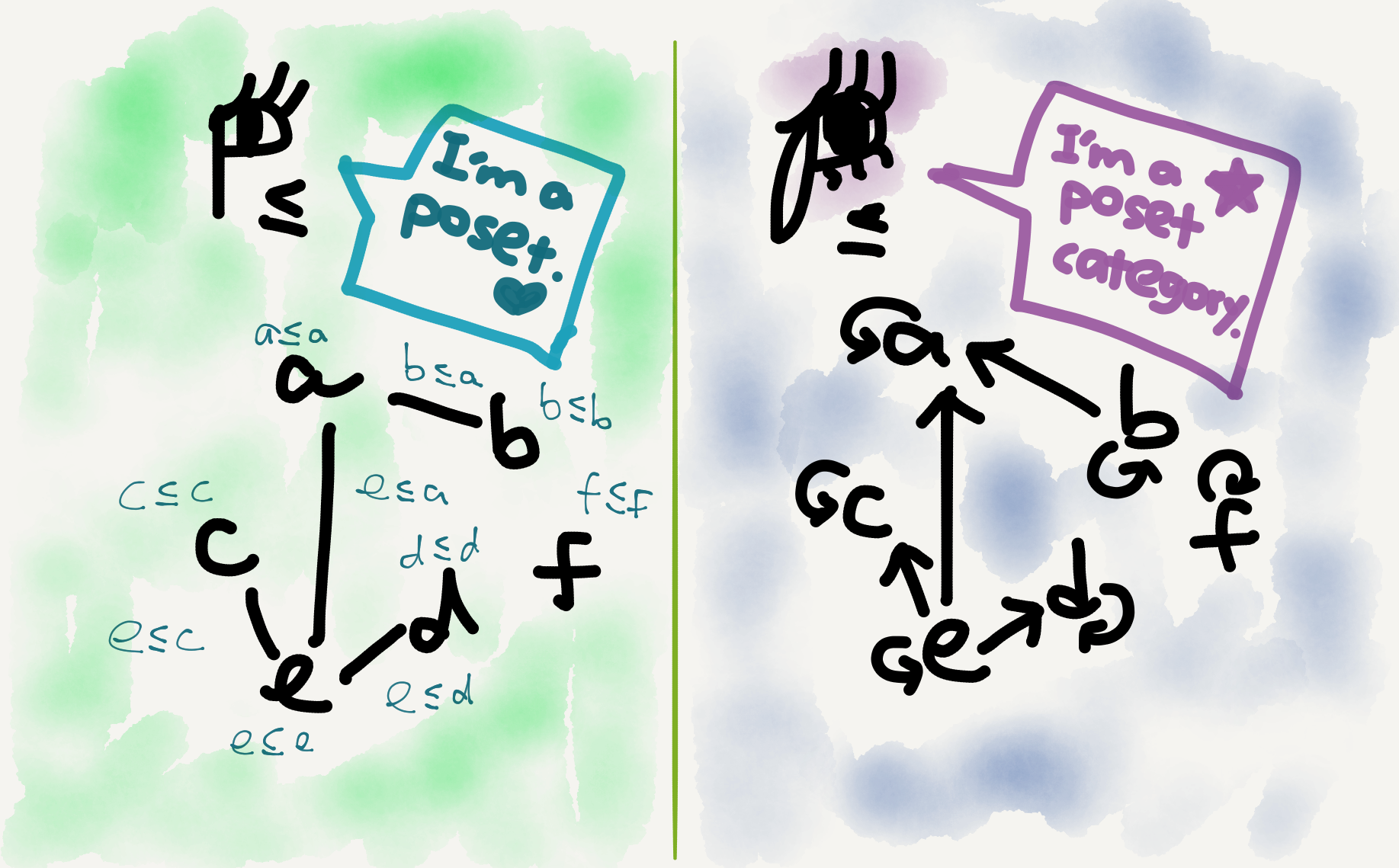

The poset category

A poset as defined above is a very categorifiable entity, and a categorified poset can be called a poset category or more verbosely “a poset viewed as a category” (I personally prefer the shorter name). The objects in a poset category are just elements of the underlying poset, and the arrows are just instances of the partial order.

When viewed as categories, two posets can be related by functors. A functor between two poset categories is just a monotone function (i.e., an order preserving function) between the underlying posets.

[A] function $f$ from $S$ to $T$ is monotone (increasing), isotone, weakly increasing, or order-preserving if it preserves $\le$: \[ x\le y \Rightarrow f(x)\le f(y) \] for all $x,y$ in $S.$ (nLab)

One thing I especially like about poset categories is that their hom-sets are extremely simple—they are either empty (when the two objects aren’t in the partial order) or singleton (when the two objects are in the partial order). So, instead of calling them “hom-sets” we might as well just call them “hom-booleans”—for any two objects $x,y$ in a poset category, their hom-boolean $\mathrm{hom}(x,y)$ is either “true” (or 1), when there is an arrow from $x$ to $y,$ or “false” (or 0), when there isn’t. Indeed, Fong & Spivak give the following theorem in their discussion on enriched categories:

There is a one-to-one correspondence between preorders and $\mathbf{Bool}$-categories. (Seven Sketches, p. 57)

Galois connection

Adjoint situations between posets had long been recognized and studied before the advent of category theory, under the name Galois connection. This name is still in common use nowadays even among categorists, though its meaning has shifted a bit. An adjunction between poset categories is more precisely a monotone Galois connection, while the original proposal Galois connection, as part of the Galois theory, was actually antitone.

The history of Galois connection is just as legendary as its name. Its inventor, Évariste Galois, developed his mathematical theories as a teenager and sadly died in a (probably romantically motivated) duel. I feel so ashamed that I didn’t study as hard as Évariste when I was a teenager (at least not in math).😰 I read a lot of (literary) books and learned several languages; I was also very fond of pop music and TV shows. But I wish I had spent more time studying math.😝

The connection

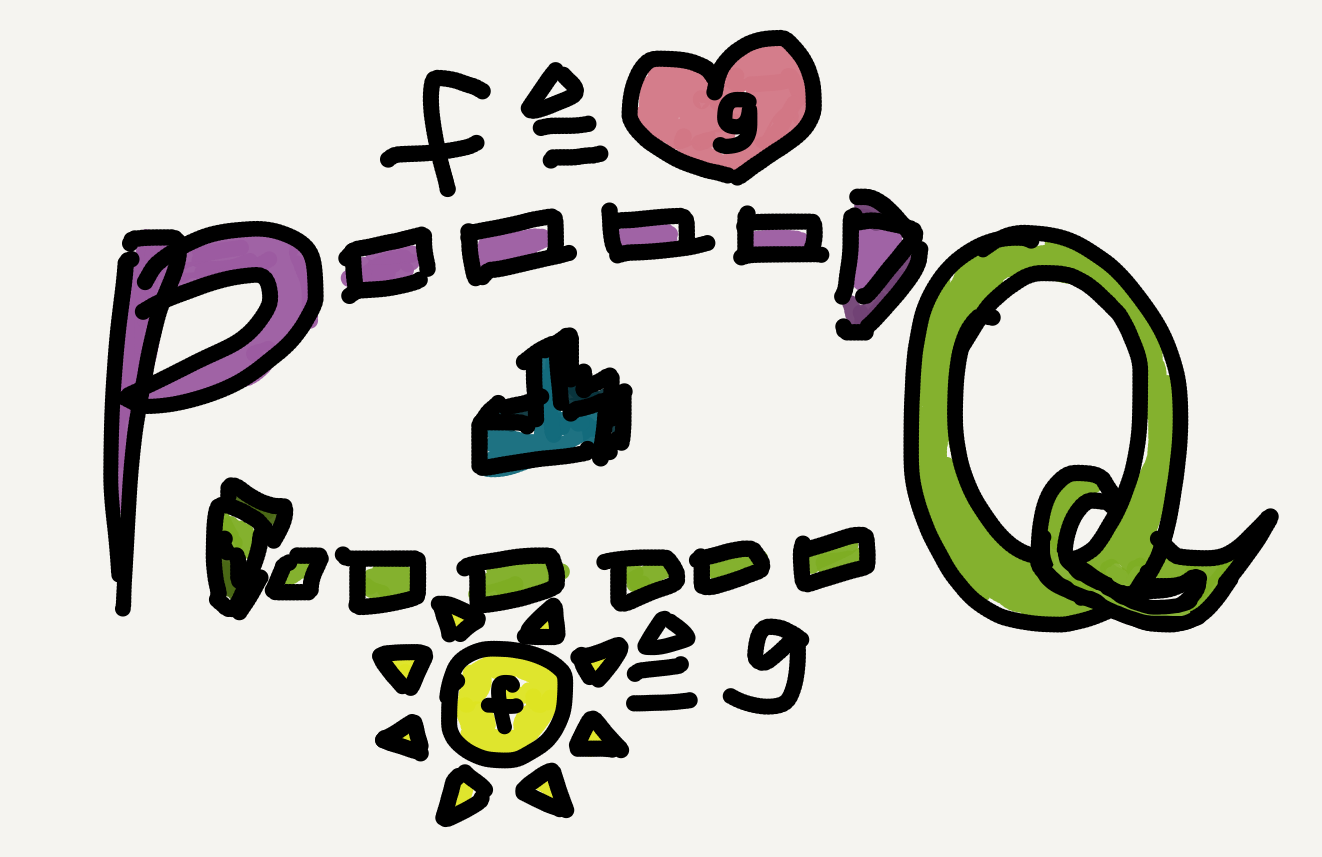

Since nowadays when people say “Galois connection,” especially in category theory, they usually mean the monotone one, hereafter I’ll just follow this convention and restrict the term Galois connection to its monotone case. A Galois connection between two poset categories $\mathbb{P}_\le$ and $\mathbb{Q}_\sqsubseteq$ can be displayed as follows:

The adjunction-induced hom-set isomorphism in the case of Galois connection simply says that the following two inequalities are in a one-to-one correspondence: \[ \forall p\in\mathbb{P}, q\in\mathbb{Q},\; f(p) \sqsubseteq q\; \mathrm{ iff }\; p\le g(q). \] The shift from arrows to less-than-or-equal-to signs is motivated because an arrow in a poset category is just an instance of its partial order relation.

The interlocking inequalities may look weird for beginners. I remember when I first learned the concept, it took me quite a while to get used to the idea that a certain element in one poset was systematically (and “weirdly”!) connected to a certain element in another poset (e.g., $p$ and $q$ in the above diagram)—and it felt even “weirder” that this connection was expressed in inequalities rather than equations. It was really only after I had learned the whole adjunction theory as well as applied it to my own research that I finally developed an intuition for the cross-categorically “syncing” arrows. But yes, the poset case is indeed a good and very much simplified example to help beginners learn adjunction.

The (co-)unit

The unit and co-unit in a Galois connection can be straightforwardly specified by the “flipping identity” trick; namely, by setting one side of the adjunction-induced isomorphism as an identity arrow and flipping it to the other side.

For example, in the following diagram by setting $f(p)\rightarrow q$ as $f(p)\rightarrow f(p)$ (i.e., by setting $q$ as $f(p)$) we get a $\mathbb{P}$-arrow $p\rightarrow g(f(p)),$ which is precisely the adjunction’s unit component at $p.$ By the same token, we can get a co-unit component of the adjunction at $q$ (by setting $p$ as $g(q)$ and flipping $1_{g(q)}$ into $\mathbb{Q}$).

What do the unit and co-unit of a Galois connection mean? In my experience it’s most intuitive to perceive them as results of functorial round trips (I’ve wrote about this round-trip method in my Sep 8 post). Once we replace the arrows with less-than-or-equal-to signs, it becomes self-evident that the unit component $\eta_p$ simply says $p$ “enlarges” (or more precisely “doesn’t shrink”) after the functorial round trip $g\circ f$, and the co-unit component $\varepsilon_q$ says $q$ “shrinks” (or more precisely “doesn’t enlarge”) after the functorial round trip $f\circ g$.

Adjoint functor theorem

There’s a well-known theorem in category theory called the adjoint functor theorem, which basically says that under certain conditions (regarding limits and colimits) the left and right adjoints in an adjunction are determined by (and hence can be expressed in terms of) each other. In other words, once we know either functor in an adjoint pair we have a way to accurately formulate the other.

This theorem, originally proposed by Peter Freyd in his 1964 paper “Abelian categories,” has a nice instantiation in poset categories, which says that if the posets in question have all meets/joins (these are the poset versions of limits/colimits), then in a Galois connection between them the left/right adjoint, if it exists, is fully determined by the other adjoint functor qua monotone function.

To illustrate, let’s try to express the right adjoint $g$ of a Galois connection $\mathbb{P}_\le\colon f\dashv g\colon\mathbb{Q}_\sqsubseteq$ in terms of $f,$ in a context where $f$ is already known to us. What we know for sure (with or without the Galois connection) is: since $g$ is a functor, to define it we just need to define a unique $\mathbb{P}$-object for each $\mathbb{Q}$-object. So the question is, Given any $q\in\mathbb{Q}$ what’s $g(q)$?

The Galois connection says $f(p)\sqsubseteq q$ iff $p\le g(q).$ So, although we don’t know what $g(q)$ is, we do know what condition it should satisfy in order for $g$ qualify as our desired right adjoint—$g(q)$ must be greater than or equal to all such $p$s that make the inequality $f(p)\sqsubseteq q$ hold. Since this “all such $p$s that…” clause gives rise to a set comprehension $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\},$ the condition $g(q)$ must satisfy is essentially that $g(q)$ be greater than or equal to this set. In other words, $g(q)$ must be an upper bound of this set.

Moreover, $g(q)$ is not just any upper bound of the set—it actually is the set’s least upper bound (aka join). To see why let’s set $p=g(q).$ We’re allowed to do so because $p$ and $q$ are both freely chosen from their ambient categories. Once we’ve done this replacement, we immediately have $f(g(q))\sqsubseteq q$ by flipping $g(q)\le g(q)$ via the Galois connection. But since our set comprehension $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}$ denotes the set of all $p$s that makes $f(p)\sqsubseteq q$ hold true, any replacement of $p$ that makes the inequality hold must also be in the set. Hence, $g(q)$ is in the set (because $f(g(q))\sqsubseteq q$).

Now, since (i) $g(q)$ is an upper bound of $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\},$ and (ii) $g(q)$ is in $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}$, we can safely conclude that $g(q)$ is just the least upper bound or join of $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}.$ An alternative (and perhaps more accurate, considering $g(q)$ must be in the set) way of saying this is that $g(q)$ is the maximum of $\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}.$ We now have an $f$-based definition for $g$: \[ \forall q\in\mathbb{Q},\; g(q) = \vee\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}\; \text{or perhaps better} \] \[ \forall q\in\mathbb{Q},\; g(q) = \mathrm{max}\{ p\mid f(p)\sqsubseteq q\}. \] That is, for all $q$ in $\mathbb{Q}_\sqsubseteq,$ we first find the set of all $\mathbb{P}$-elements whose image in $\mathbb{Q}$ are less than or equal to $q.$ Then, we go on to locate the maximum of this set of $\mathbb{P}$-elements. If the maximum exists, that’s just the value $g(q)$ we want; if it doesn’t exist, then there’s not such right adjoint $g$ (i.e., the problem has no solution). Notice that even though such a $g(q)$ doesn’t necessarily exist, when it exist it must be unique; that is, it’s not disturbed by the “up to isomorphism” ideology, because due to antisymmetry isomorphic elements in posets are literally the same.

For the remaining part of this article see my next post “Category theory notes 20: Category theory for posets (Part 2).”

Leave a comment