In my previous post “Category theory notes 19: Category theory for posets (Part 1)” I began writing about the “poset versions” of some category-theoretic results, including the categorification of posets as poset categories and the Galois connection (i.e., adjunction for posets). In this very last post of the entire series I’ll finish off what I started last time, by commenting on reflective subcategories and the Yoneda lemma adapted to posets. Then I’ll finalize the series with a short epilog.😊

Reflective subcategories for posets

In my Sep 14 post I wrote about reflective subcategories, which are associated with an inclusion functor. Recall that the reflective subcategory situation is an adjoint situation where the inclusion functor has a left adjoint (i.e., the inclusion itself is a right adjoint).

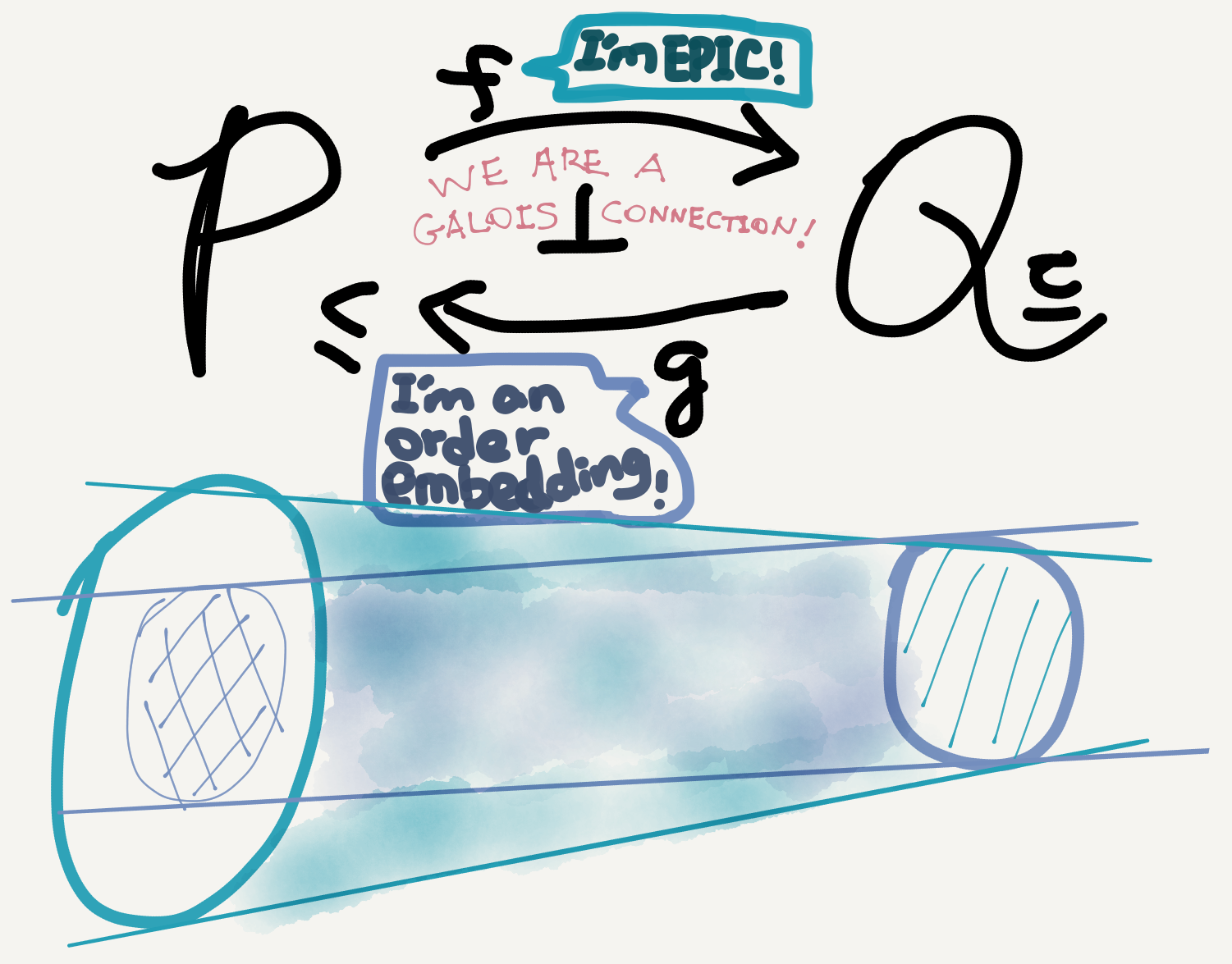

The poset version of a reflective subcategory is surprisingly simple—it’s just a subposet. And the adjoint situation is still there, which is sometimes called a “right perfect Galois connection” (Erné 2004)—because the left adjoint is “epic.”

Since there’s at most one arrow between any two objects in a poset category, a functor between poset categories is always faithful—there’s no chance for the hom-set mappings to be noninjective after all. However, such a functor is not necessarily full, because there may be arrows in the target category that don’t exist in the source category.

When the functor is indeed full, and when it’s additionally injective on objects, we actually have an order embedding, as defined below:

[A]n order embedding is a special kind of monotone function, which provides a way to include one partially ordered set into another.

[G]iven two partially ordered sets $(S,\le)$ and $(T,\le),$ a function $f\colon S\rightarrow T$ is an order embedding if $f$ is both order-preserving and order-reflecting, i.e. for all $x$ and $y$ in $S,$ one has \[ x\le y \text{ if and only if } f(x)\le f(y). \] Note that such a function is necessarily injective [on elements], since $f(x)=f(y)$ imples $x\le y$ and $y\le x.$ If an order embedding between two posets $S$ and $T$ exists, one says that $S$ can be embedded into $T.$ (Wikipedia)

N.b. an order embedding is not an inclusion, but it’s as good as one up to isomorphism. Thus, if a poset can be embedded to another, the former is isomorphic to a subposet of the latter, and the whole situation may perfectly be described as a reflective subcategory situation (up to isomorphism).

In my Sep 5 post I wrote about two half-inverse arrows between categorical objects, one called a section (or split monomorphism) and the other called a retraction (or split epimorphism). A right perfect Galois connection can be viewed as a section-retraction situation lifted to the functorial level, because a section between posets is just an order embedding (this is an established result) and a retraction between posets, being a split epimorphism, is automatically epic.

A section-retraction situation in $\mathbf{Set}$ creates a sorting or partitioning scenario (see Lawvere & Schanuel’s textbook for details), with a smaller set (i.e., a “retract”) sorting into a bigger set. This scenario is retained in the “lifted section-retraction situation,” where the reflective subcategory can be viewed as a special subposet (up to isomorphism) that partitions its “parent category,” with each part being indexed by an element in the subposet (i.e., an object in the reflective subcategory).

Of course, we may also just let the section and retraction remain at the morphism level, by treating the two posets in question not as categories but as objects in $\mathbf{Pos}$—the category of posets. In this category the arrows are just the monotone functions between posets. Perspective shifts like this are absolutely normal in category theory!

Yoneda lemma for posets

In my Sep 12 post I wrote about the Yoneda lemma. Recall that an important corollary of the Yoneda lemma is that any object in any category can be completely determined by the relationships from all other objects to it in the same category. Thus, we can learn everything we need to know about an object by studying how other objects in its locality are related to it.

In a poset category the “relationships” are just instances of a partial order, and so “the relationships from all other objects” to an object is just the collection of two types of data: the existence of a partial order instance and the absence thereof. In other words, the action of the Yoneda functor \[ y\colon \mathbb{C}\rightarrow\mathbf{Set}^{\mathbb{C}^{\mathrm{op}}} \] on a poset category $\mathbb{P}_\le$ effectively associates a subposet of $\mathbb{P}$ for each object $p\in\mathbb{P},$ which contains all the $\mathbb{P}$-objects related to $p$ “from below.” In order theory this is known as the principle lower set of $p,$ denoted by $!p.$ In other words, each poset element is completely determined by its principle lower set. This is the poset version of the Yoneda philosophy.

Takeaway

- Many general category-theoretic results have restricted and simpler versions in the context of posets. Studying such “poset versions” can help beginners quickly develop an intuitive knowledge of category-theoretic ideas.

- An adjoint situation between poset categories is a (monotone) Galois connection, and the adjunction-induced hom-set isomorphism in a Galois connection is just a one-to-one correspondence of inequalities.

- By using the adjoint functor theorem we can actually “calculate” the left/right adjoint of a Galois connection provided that the other adjoint is given and the relevant meets/joins exist.

- A reflective subcategory situation for posets is a right perfect Galois connection, which can be conceived as a section-retraction situation.

- The Yoneda functor for posets maps elements in a poset to their principle lower sets, which provide a channel for us to learn about poset elements without directly looking at them.

Epilog

In the past few weeks I went through my learning notes of category theory and compiled some of them (mainly those on issues that had puzzled me) into this blog series. Back in this time last year, I still knew very little about category theory. Well, I knew what a category or a functor was and could draw a few commutative diagrams, but slightly more convoluted concepts like half inverses, the interchange law, and adjunction were still pretty much beyond me, not to mention widely recognized “hard nuts” like the Yoneda lemma.

So, standing here and now, I’m happy about my “intellectual growth” over the past year. I’ve not only learned almost everything in basic category theory (at least almost everything there is in introductory textbooks) but also applied some of its results to solving linguistic problems in my dissertation. This clearly shows everything can be learned if you have the will.

As I mentioned in the first post of this series, category theory is so abstract that everything else just looks less abstract. I think my brain (or at least my way of thinking) has been rewired in my learning process. Many works (e.g., those in mathematical logic and theoretical computer science) that I used to find difficult (or at least time-consuming) to understand now look a lot easier. I think learning category theory has definitely helped me in this respect.

Of course, the more you know, the more you know that you don’t know. It was only when I more or less reached the end of my textbooks that I realized how much more there was still to learn in the subject, from fashionable things like monoidal categories and higher categories to less cutting-edge but somewhat mystical things like the tensor ($\otimes$) and the dagger ($\dagger$)—no idea why but those two symbols have intimidated me… Category theory, especially applied category theory, is still a fast-developing field, and I’m glad that I’ve made its acquaintance while I’m still young.

Oops the “short” epilog is getting long… so I’ll just stop. While this very series has completed, my learning journey hasn’t, nor has my application of category theory in my research. So perhaps in the future I’ll write more posts or even series on the topic.

This is the end. And this is not the end…

Leave a comment