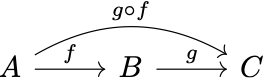

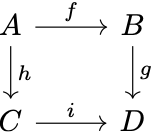

Arrows are so vital to category theory that Awodey jokingly refers to the theory as “archery” (Category Theory, p. 2). Given two objects in a category, an arrow between them, if it exists, simply connects them: $A \rightarrow B.$ And if one arrow’s head overlaps with another’s tail, then the two arrows combined necessarily correspond to a third arrow in the category. For example, in the diagram

there are three arrows $f,g,$ and $g \circ f.$ Such arrow chaining, called composition, is part of what it means to be a category.

We needn’t care about what the objects $A, B, C$ or the arrows $f, g, g\circ f$ stand for. Category theory is the abstract study of objects and arrows, and everything works just fine even if we don’t assign interpretations to them. From a linguistic perspective, we can view this abstract theory of categories (or metacategories in Mac Lane’s words; CWM, p. 7) as a purely syntactic system without prespecified semantics. The objects and arrows are its vocabulary, composition and the like are its rules, while the possible interpretations of this syntax (which are presumably a lot!) are a secondary, domain-specific issue.

Objects, arrows, and composition are part of the axiomatic definition of a category.

Parallel arrows

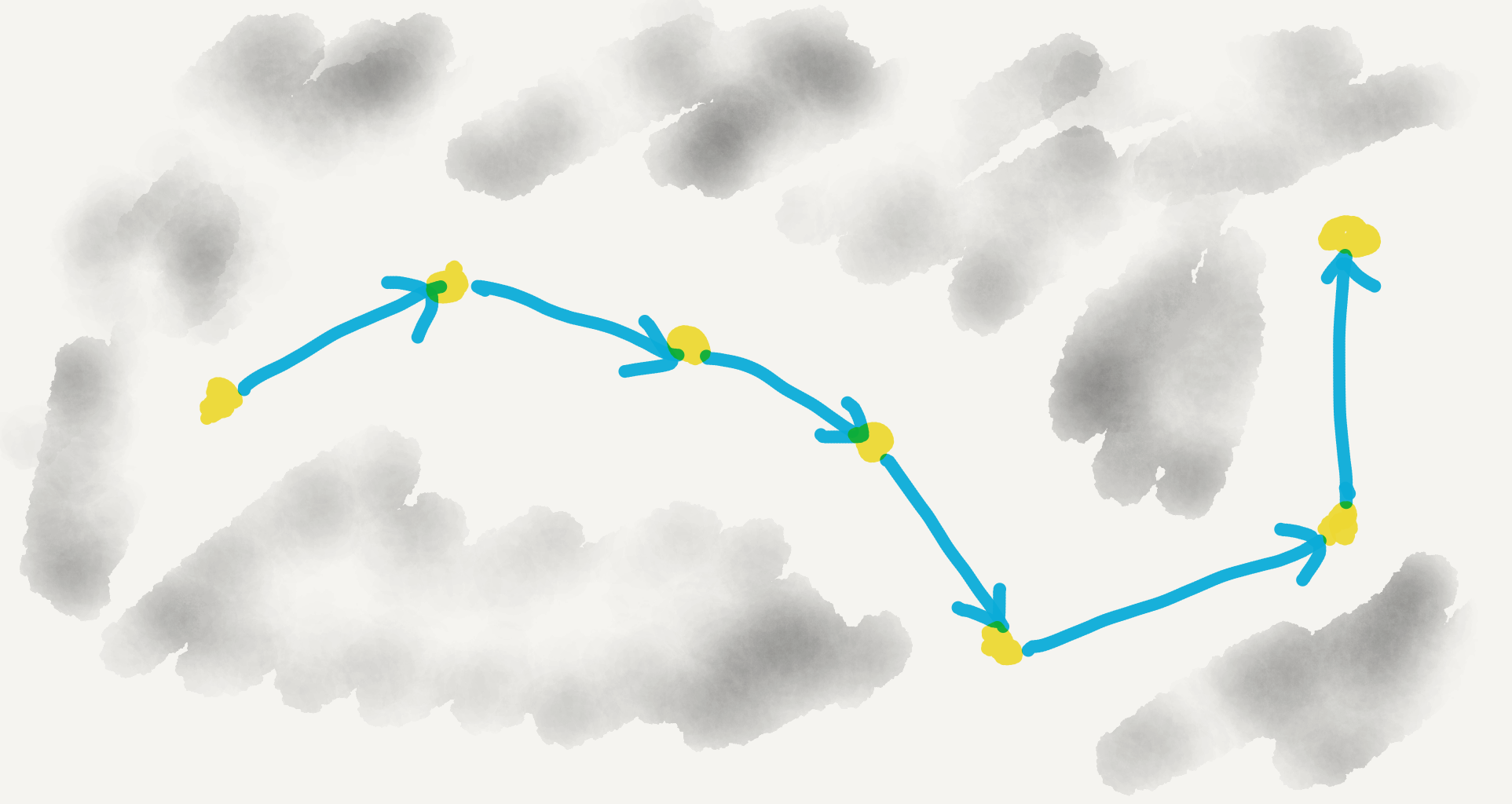

Little diagrams like the one above are standardly given in textbooks. Despite their convenience, however, they may become a source of confusion for beginners. The problem is that they are too neat—to the extent that things begin to look contrived. I remember when I first started learning category theory, I almost believed that such neat diagrams were all there was to categories—that they were perfect depictions of the categories behind them. Take a bunch of objects, connect them by composable arrows, and voila—we have a category! So, in my naive imagination category theory was not only archery but also astrology. 😂

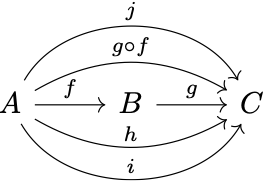

But such neatness was just my illusion. I later realized that there could actually be multiple arrows between each pair of objects. In hindsight, I can’t believe that I hadn’t realized this right away. But again, that might be a sign that textbooks should give this point more emphasis so that students don’t miss it. So, in the above diagram $g \circ f$ is probably just one of the many arrows connecting $A$ and $C$.

Crucially, among all the $A \rightarrow C$ arrows only one is the composite of $f$ and $g$, while all others can just be its random neighbors. In fact the arrow space between each pair of objects can be highly populated. How populated? More than sets can describe! It’s a basic mathematical fact that there are collections larger than sets. Only when the arrow collection between two objects $X$ and $Y$ is “small” enough can we call it a set, or more precisely a hom-set, denoted by $hom(X,Y)$. For instance, the collection of arrows between $A$ and $C$ in the above diagram, when it’s a set, is written $hom(A,C).$ The pronunciation of $hom$ is nonunanimous. I’ve heard both /hoʊm/ and /hɑm/ from distinguished experts. Etymologically hom comes from homomorphism, which might explain the pronunciation nonunanimity.

Considering the possibly numerous or even countless parallel arrows, the “true colors” of categories may be much less neat than what we see in textbook diagrams. A fully realistic depiction of a category may well be a clump of black clutter whose details are indiscernible to the human eyes. Maybe that’s why textbooks choose to draw out only those arrows relevant to the topic under discussion.

There are also less cluttered categories. A basic example is the categorical conception of a poset—a set equipped with a reflexive, transitive, and antisymmetric binary relation called a partial order. The objects of this category are elements of the set, and the arrows are instances of the partial order. Since a relation either holds or doesn’t hold with no third possibility, between any two objects in a poset category there is either no arrow or only one. That is, the hom-sets in a poset category are either empty or singleton. A special type of poset is a chain, like the Big Dipper above!

In a poset category arrow composition is defined by transitivity (e.g., if $A\le B$ and $B\le C$ then $A\le C$). Since in a category all composable arrows must actually compose, composite arrows are usually omitted when the definition of composition is not the topic being discussed. This convention makes diagrams even neater.

Commutative diagrams

What’s the correlation between composite arrows that are parallel? Well, sometimes they may be equivalent in an algebraic sense, just like $1+4=2+3.$ And a diagram where all parallel composite arrows are equivalent is said to commute. For example, in the diagram

,

,

if $g \circ f = i \circ h,$ then the diagram is commutative. Commutative diagrams are another vital part of category theory, and they are closely related to arrow composition.

Normally one wouldn’t expect something as clearly defined as commutative diagrams to be confusing, but the notion—or more exactly what’s left implicit of it—did confuse me for a while. My confusion was, How can we tell whether two paths are equivalent or not?

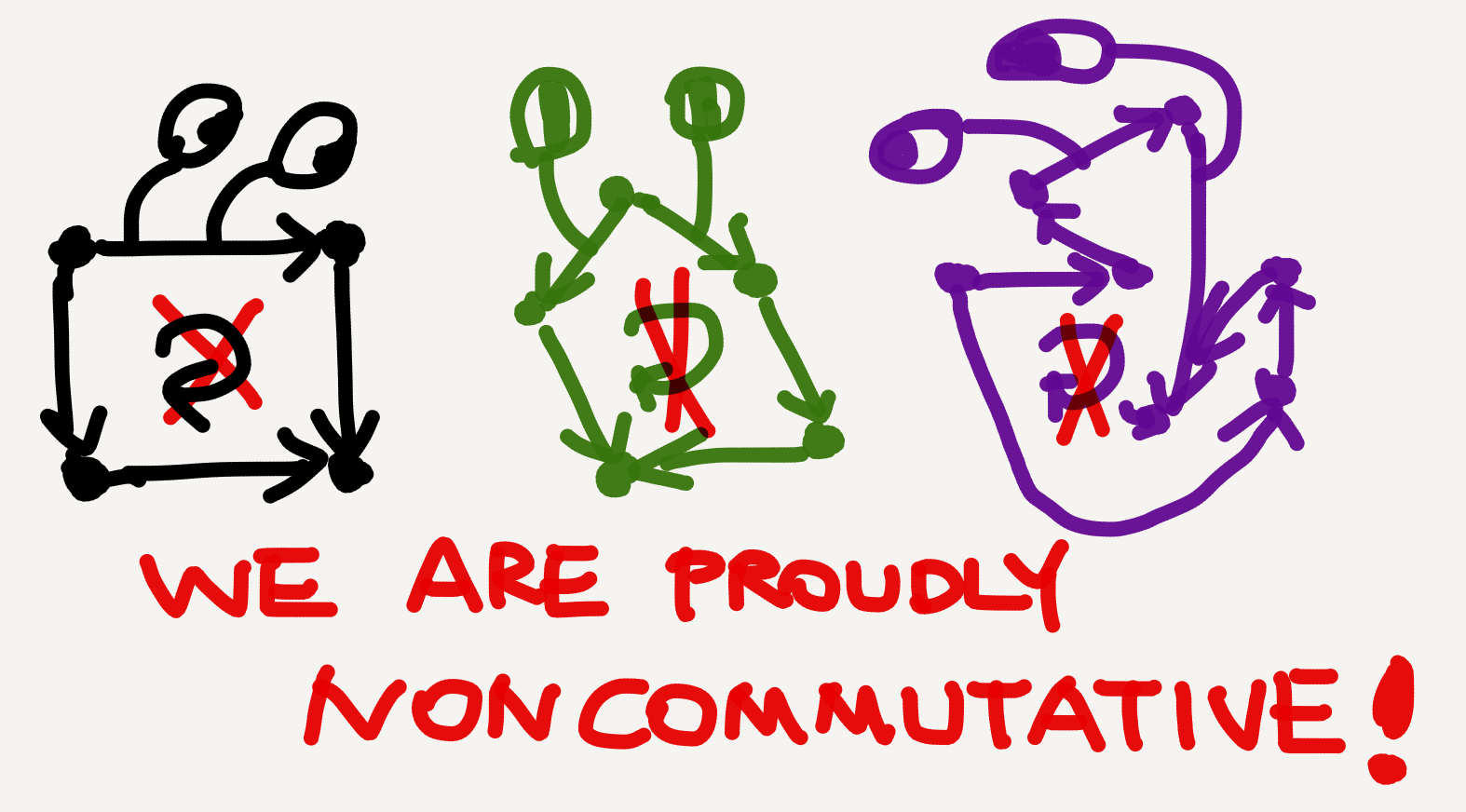

Initially I had thought two paths sharing the same source and target were equivalent—all roads lead to Rome! But soon I realized there must be something wrong with this idea, because if it were true then all parallel arrows would end up being equivalent; in other words, all diagrams would be commutative. But if that were the case, why would mathematicians bother coming up with a notion of commutativity at all, let alone cherishing it so much? If that were the case, saying a diagram is commutative would be like saying a forest has trees!

In hindsight, a major cause of my confusion was that the introductory texts I used only illustrated commutative diagrams but not noncommutative ones, which gave me the false impression, perhaps subconsciously, that commutativity came for free, or at least at a very low price—as if to make a diagram commute all we needed to do was draw parallel paths between objects.

But that’s just another illusion from the neat textbook diagrams. Path equivalence is essentially an algebraic property and must be proven algebraically. When two paths can’t be proven equivalent, then they simply aren’t, and the diagram doesn’t commute. Noncommutative diagrams aren’t outlaws. They should be given equal status in pedagogical materials as commutative diagrams so that beginners, especially those with less mathematical experience, can get a more balanced understanding of commutativity.

Smith’s 2018 draft textbook Category Theory: A Gentle Introduction (henceforth Gentle Intro) has the clearest explication on this issue I’ve ever seen:

But note: to say a given diagram commutes is just a vivid way of saying that certain identities hold between composites – it is the identities that matter. And note too that merely drawing a diagram with different routes from e.g. A to D in the relevant category doesn’t always mean that we have a commutative diagram – the identity of the composites along the paths in each case has to be argued for! (p. 29)

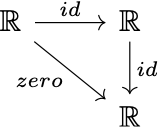

Tai-Danae Bradley gives a simple example of a noncommutative diagram in her blog post “Commutative diagrams explained”: the following diagram of real-valued functions,

where $id$ is the identity function and $zero$ is a constant function that maps all real numbers to $0$, obviously doesn’t commute, because the parallel paths $\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ don’t return the same output for the same input.

Bradley’s example essentially demonstrates a set-theoretic criterion of arrow equivalence—function extensionality. This principle states that two functions are equal iff their values are equal at every argument. Since $id\circ id$ and $zero$ don’t return equal values for every real number, they as functions are not equal and hence as arrows are not equivalent.

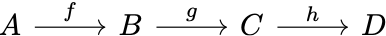

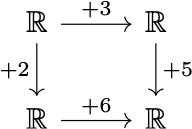

Adapting Bradley’s example, we can construct a commutative diagram as follows:

Since for any real number argument $(+5)\circ(+3)$ and $(+6)\circ(+2)$ return the same value, they are equal functions and equivalent paths, whence the diagram commutes. Admittedly, not all diagrams can be checked for commutativity in this way, because many categories have nothing to do with sets and functions. But the caveat remains the same: we can’t declare a diagram commutative on a whim but can only verify (or falsify) commutativity via a proof.

Takeaway

- There can be multiple parallel arrows between a pair of categorial objects. Textbooks don’t depict all of them in diagrams because many are irrelevant to the topic(s) under discussion.

- Commutativity doesn’t come for free but must be proved, by showing that the two sides of a hypothetical path equation are really equal.

- Noncommutative diagrams are also valid diagrams and shouldn’t be glossed over in textbooks for total beginners.

- In categories where arrows are functions, commutativity can be checked via function extensionality.

Leave a comment