Category theory is spectacularly big. But exactly how big is it? Consider a set $A$. It can hold a huge number of elements, say, all grains of sand on Earth. That’s already too humongous a size for my mundane brain to imagine, but in the category $\mathbf{Set}$ it just takes up the space of a single object, alongside many other sets $B, C, D,$ etc. For example, let $B$ be the set of all human beings that have ever existed on Earth, $C$ the set of all natural languages that have ever been spoken, and $D$ the set of all puli dogs. I guess none of the four sets can be considered “big” in a mathematical sense—they all have a finite number of members and can be easily compared for cardinality (presumably $D<C<B<A$).

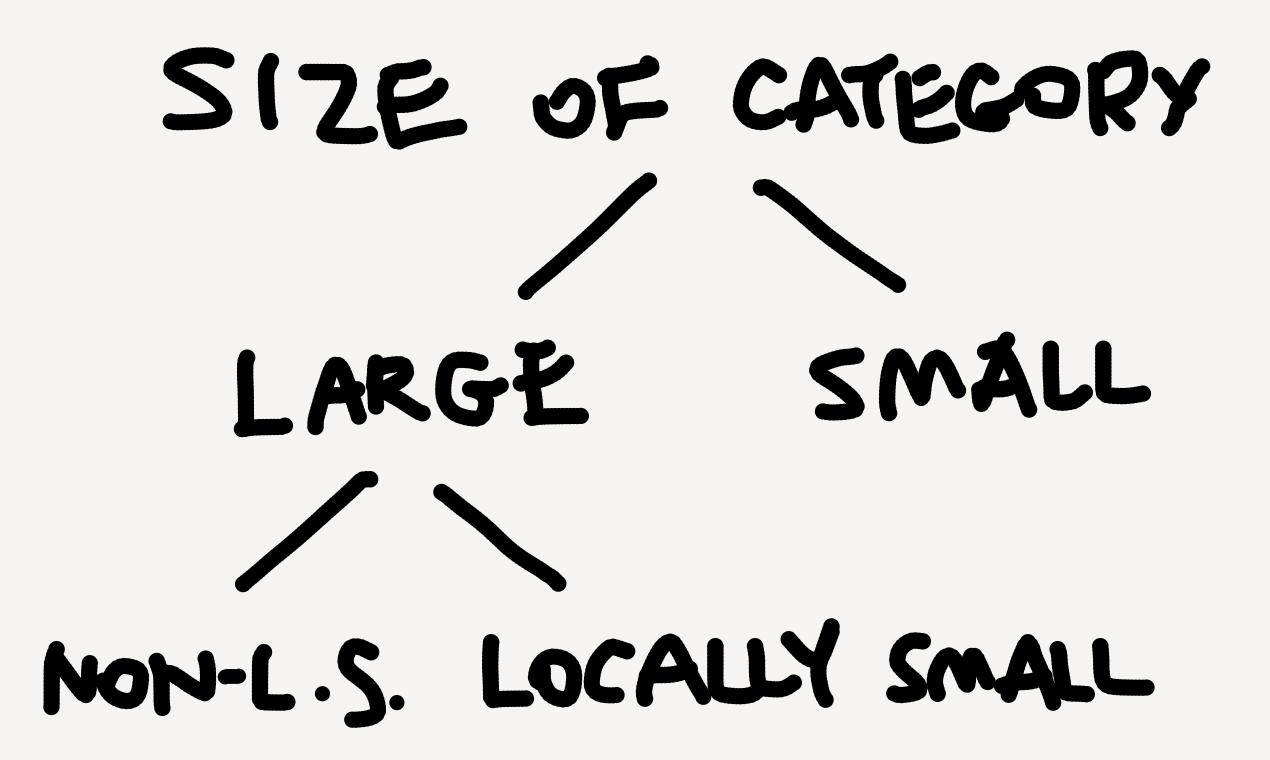

Category sizes

$\mathbf{Set}$ is the category of all sets and functions, which surely is enormous. Yet in the world of categories it’s just a single category, and a locally small one (see this Quora page for a beginner-friendly explanation). In category theory there are three conventional sizes of categories. A category is

- small if both its object collection and its arrow collection are sets;

- large if both its object collection and its arrow collection are proper classes;

- locally small if, even though its object collection is a proper class, the arrows between any two objects in it form a set (i.e., a hom-set; see my Aug 28 post).

Crucially, here “small” and “large” shouldn’t be understood in the everyday sense. They should be recognized and learned as mathematical terms instead. Locally small categories are a subclass of large categories. So, if a category is locally small, it’s automatically large, but not vice versa. The classificatory relation between the three sizes is as follows.

We linguisticians love cross classifications. To cross-classify category sizes we need three binary features: [object-collection (oc): ±set] (whether the object collection is a set), [arrow-collection (ac): ±set] (whether the arrow collection is a set), and [hom: ±set] (whether the hom-collections are sets).

| [oc:±set] | [ac:±set] | [hom:±set] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| small | + | + | + |

| locally small | - | - | + |

| (properly) large | - | - | - |

| ? | + | - | ± |

As the table shows, the three features cross-classify categories into five licit sizes,1 among which three are officially recognized. What are the [[oc:+set],[ac:-set],[hom:±set]] sizes? I don’t know.🤷♂️

Beyond the above cross classification, some people also speak of a fourth category size, very large (see this nLab page), which describes a category whose objects are all categories, including the properly large ones (this is what Mac Lane means by metacategory in CWM). But nowadays that concept is not often used and certainly not mentioned in many introductory textbooks.

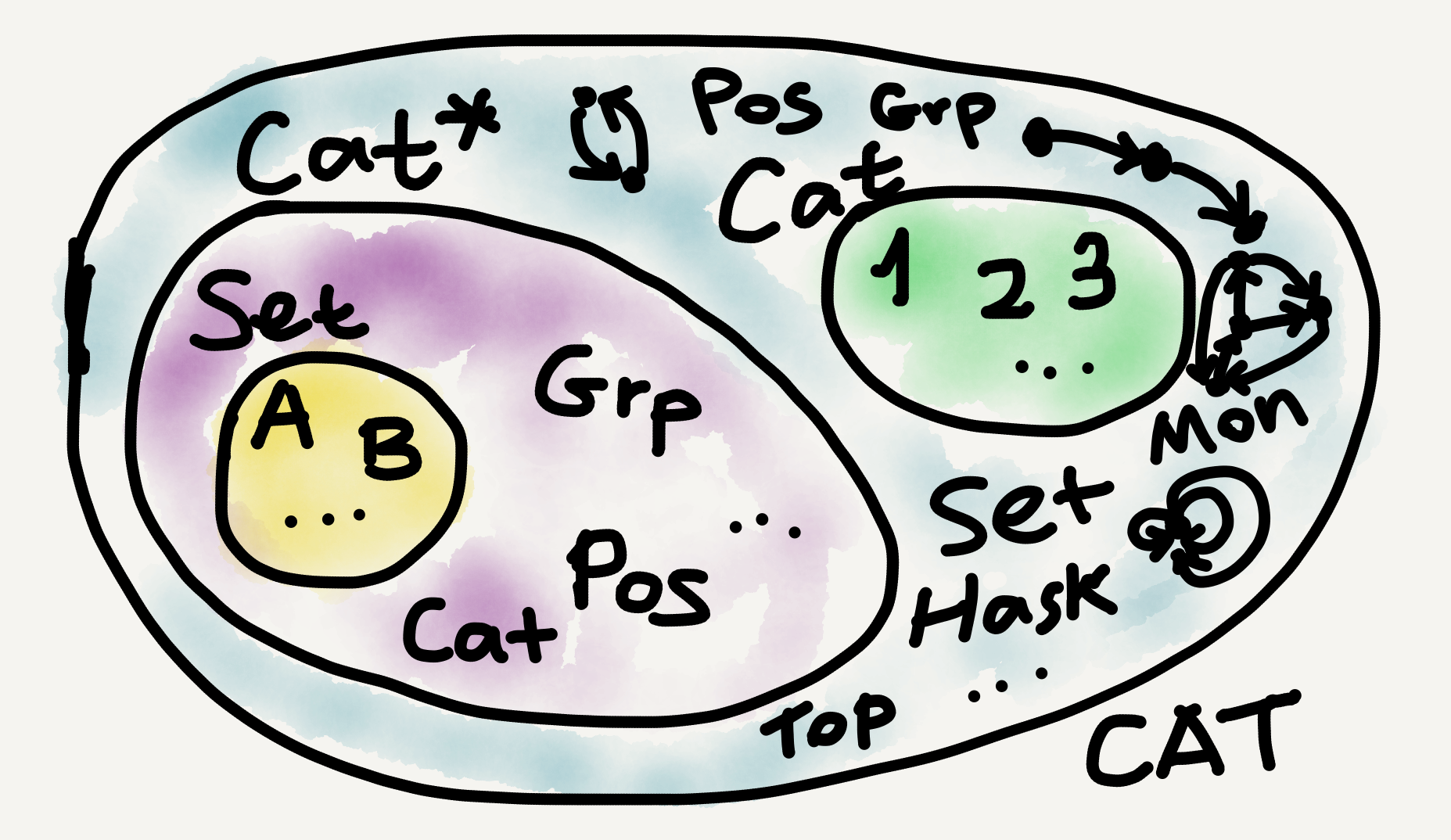

Examples

To illustrate, many of the categories standardly studied in mathematics, such as $\mathbf{Set}, \mathbf{Grp},$ and $\mathbf{Pos},$ are locally small. By comparison, most categories of interest outside mathematics, such as the category $\mathbf{Hask}$ for Haskell types and functions, are properly small. Some specially designed “toy categories” in mathematics are also small, such as monoid categories (see my Aug 24 post), poset categories (see my Aug 28 post), and ordinal number categories ($\mathbf{1}, \mathbf{2}, \mathbf{3},$ etc.).

Properly large categories are much rarer (at least to my knowledge; see this page for a discussion): the category $\mathbf{Cat}$ of all small categories is in fact locally small; the category $\mathbf{Cat^*}$ of all locally small categories seems to be properly large (see Gentle Intro, p. 153); and the category $\mathbf{CAT}$ of all categories (large and small) is very large.

At the $\mathbf{CAT}$ scale our initial sand set $A$ is already too minuscule to be noticeable or cared about, like an amoeba in an ocean or a person in the universe. Indeed, sometimes size comparison in category theory reminds me of videos that compare celestial body sizes, like this one:

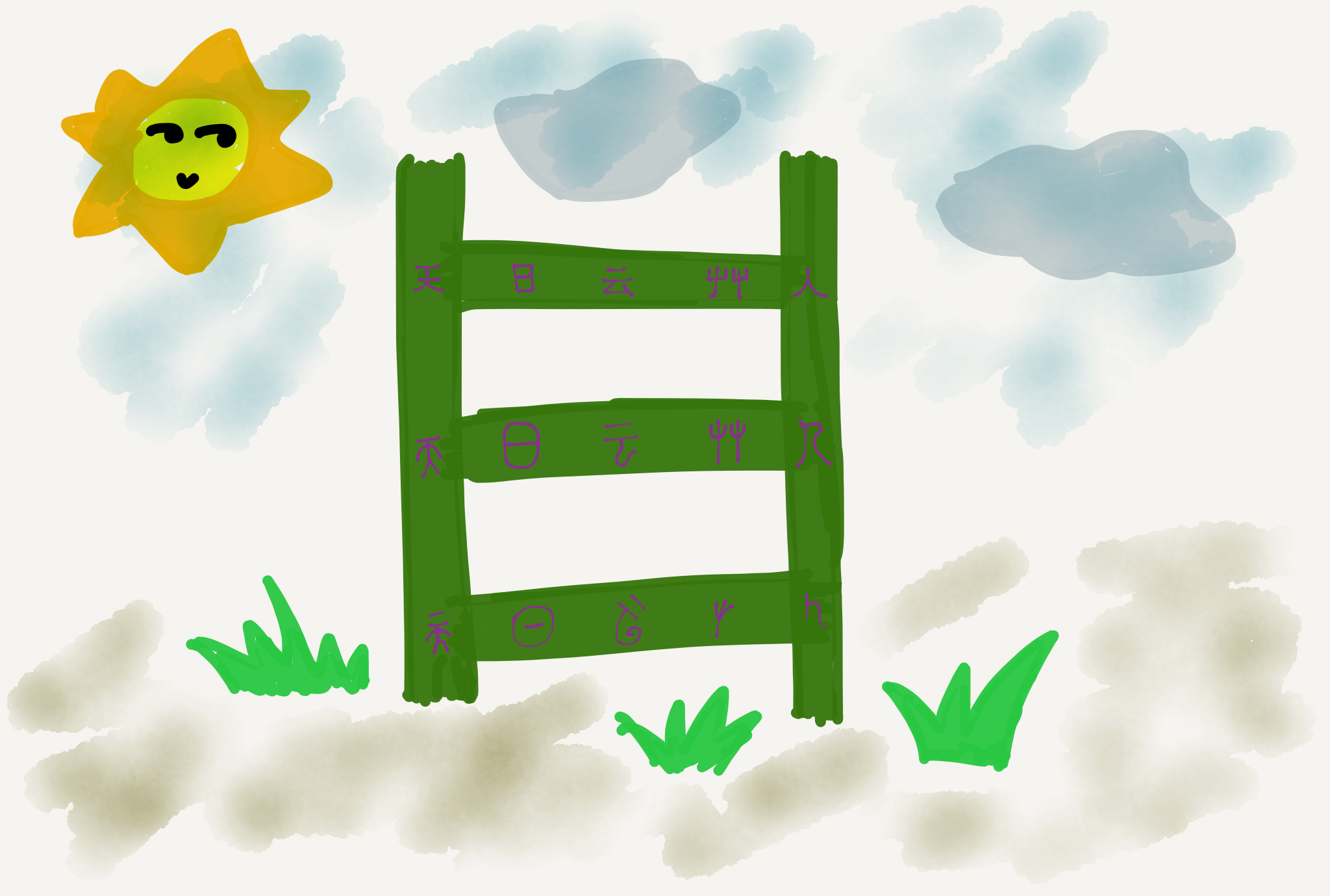

Ladder of abstraction

What good do the size-related concepts in category theory do to us nonmathematicians? In my own experience, a most important benefit I’ve got is the “ladder of abstraction” mind-set. Given a particular system, there may be multiple angles to view it. The categorical mind-set guides us to organize those angles into ascending levels of abstraction, with constructs at lower levels “feeding” constructs at higher levels.

Since I’m a linguistician, I’ll use human language as an example. At the lowest level of abstraction, a language is just a (presumably infinite) set of utterances, containing elements like apple and It’s sweet. At a higher level of abstraction, the utterances can be assigned and described by syntactic types (i.e., linguisticians’ categories), such as noun and sentence. Most people’s understanding of human language stops at this level, which is also the level of abstraction school grammars dwell in.

At an even higher level of abstraction, the numerous syntactic types can be divided into several sets, such as “nouny” types (e.g., noun, determiner, classifier) and “verby” types (e.g., verb, sentence, tense). These sets are internally structured and externally interconnected—IMHO following some simple yet powerful “templates,” which I’m inclined to call the “DNA of human language grammar.” And the abstraction continues. In my PhD dissertation I used nearly 300 pages to illustrate the intricately layered structures arising from grammatical types, and quite a few discoveries I made were inspired by category theory.

The more abstract the perspective is, the more useful category theory is.

Takeaway

- Category theory is really large-scale!

- There are three standardly recognized sizes of categories: small, large, and locally small.

- Most categories in mathematics per se are locally small, while most categories outside mathematics are small.

- Understanding the size-related concepts in category theory can help us form a highly useful ladder-of-abstraction mind-set.

Leave a comment