Sometimes our brains make connections in unexpected ways. For instance, the other day I was thinking about I Ching (can’t remember why), the ancient Chinese divination book, and an idea suddenly popped into my head: Isn’t the procedural manipulation of symbols in the divination process a sort of syntactic derivation like that in transformational-generative grammar?

The more I thought about the idea, the more curious I got, so I decided to give it a go and see if I could describe I Ching divination in linguistic terms—just for fun. This article is split into six parts:

- Part 1: What’s I Ching?

- Part 2: Structure

- Part 3: Meaning I

- Part 4: Meaning II

- Part 5: Linguistics I

- Part 6: Linguistics II

Those who already know the basics of the I Ching or are simply impatient can skip the first four parts and directly jump to Part 5.

The Classic of Changes

I Ching or Yijing (易經),1 literally “the Classic of Changes,” is the oldest and most important classic text in Chinese history. It’s also simply (and sometimes preferably) called I (pronounced “ee”), for its canonization as a Ching ‘classic text’ (in 136 B.C.E.) only happened many centuries after its birth.

As its name suggests, the I Ching is a book about changes. It models the world in terms of transitions between hexagrams, which are little pictures made up of six solid or broken lines such as ䷂ and ䷄. I find the following words from a divination website a good summary.

The I Ching’s operating principle is that change is the one constant in life, and that our lives are just a series of changes from one set of circumstances to the next.

Authorship

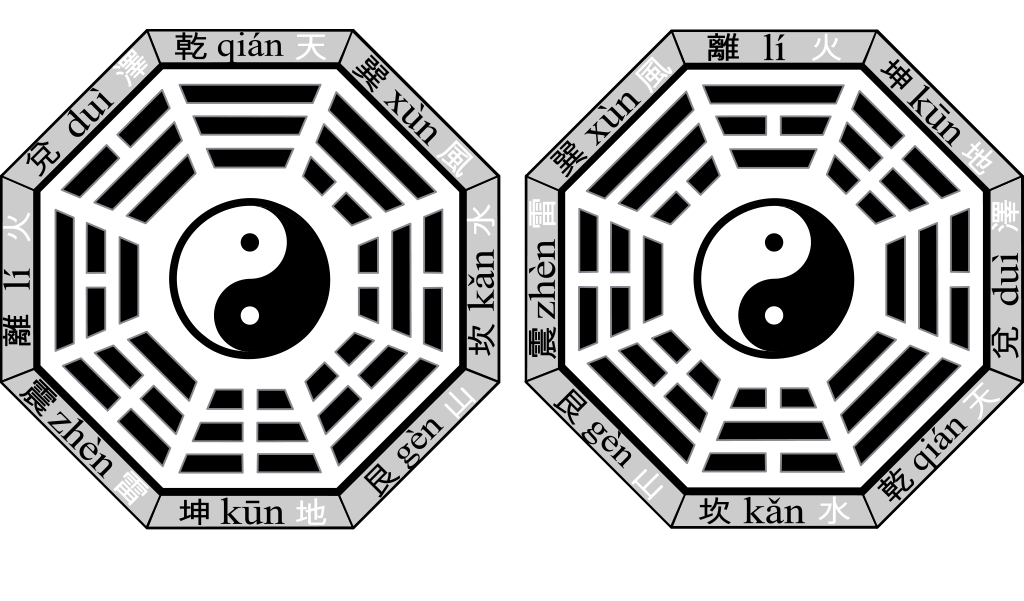

The established form of the I Ching is attributed to the Duke of Zhou (11th century B.C.E.)—hence its other name Zhou yi ‘Changes of the Zhou Dynasty’ (周易)2—but the core symbolic system of the book, including its eight trigrams and sixty-four hexagrams, is actually the work of the duke’s father, King Wen of Zhou. King Wen, on the other hand, had built his work upon that of Fuxi (21st century B.C.E.), a legendary early ruler of the Chinese civilization. The major difference between King Wen’s system and Fuxi’s system lies in their different arrangements of the eight trigrams or bagua ‘eight gua’ (八卦).

- Tā shì yí gè fēicháng bāguà de rén.

(他是一個非常八卦的人。)

"He is a very gossipy person."

The authorship of the I Ching is usually attached to all three historical/mythical figures mentioned above—together with the much younger Confucius (551–479 B.C.E.), who allegedly had added the most important commentaries to the book (called the Ten Wings) and played a crucial role in its reclassification as a philosophical book. Luckily this reclassification hadn’t taken immediate effect, though, because otherwise the I Ching couldn’t have survived Qin Shi Huang’s brutal policy of burning philosophical books and burying Confucian scholars in 212–213 B.C.E.

The content of the Changes is very deep. Its creation took the work of three sages [i.e., Fuxi, King Wen of Zhou, and Confucius] and spanned across three ancient ages [i.e., the Neolithic Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age].

(易道深矣,人更三聖,世歷三古。)

— Book of Han, Vol. 30 (1st century C.E.)

Divination

Idea

The basic idea behind I Ching divination is that every moment in spacetime is an all-encompassing picture like a holographic screenshot; everything in the moment, down to every trifling minutia (such as the occasional falling of leaves), is an indispensable piece in a unique jigsaw puzzle. As the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung comments in his foreword to Wilhelm/Baynes’ translation of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese divination method is “more akin to the perception of a work of art.” Jung further points out that the idea behind I Ching divination is similar to his own idea of “synchronicity”—the assumption that events that occur with no causal relationship yet seem to be meaningfully related are actually meaningful coincidences.

[S]ynchronicity takes the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance …. Just as causality describes the sequence of events, so synchronicity … deals with the coincidence of events. … [T]he sixty-four hexagrams of the I Ching are the instrument by which the meaning of sixty-four different yet typical situations can be determined. These interpretations are equivalent to causal explanations.

— Foreword, The I Ching or Book of Changes

In a word, in the philosophy of the I Ching there’s no real randomness. The following book excerpt also well summarizes this philosophy:

[T]he assumption of orthodox Western science that there is no meaning to be gleaned from random events was certainly not shared by the ancient Chinese. Their divinatory practices and their whole cosmology were based on a qualitative notion of time, in which all things happening at a given moment in time share some common features, are part of an organic pattern. Nothing therefore is entirely meaningless.

— The Original I Ching Oracle, Chapter 1

Method

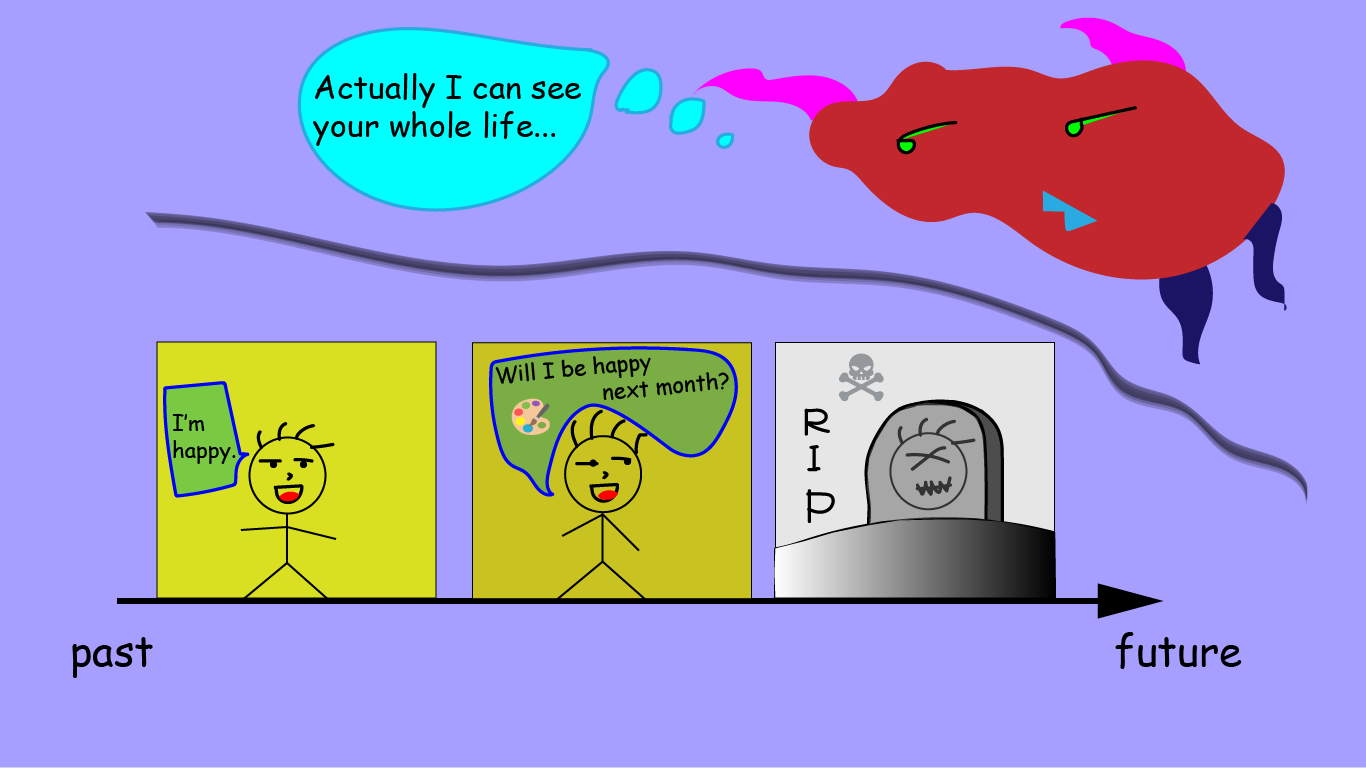

The screenshots of the spacetime moments can be observed from many angles—and for a higher-dimension creature they are indeed observable from every angle, and all at once. For us humans, however, such a bird’s-eye view is unavailable; we can only get a glimpse of the bigger picture via some sort of trick. Our tricks will no doubt look primitive and clumsy in our higher-dimension friend’s eyes, and they’ll only show us a tiny tip of a colossal iceberg, but something is better than nothing!3

Each divination method offers its own horizon-broadening trick. The trick of the I Ching is to generate random numbers, either by sorting fifty yarrow stalks or by tossing three coins. Between the two, the yarrow stalk method is the more traditional or “authentic,” but it’s also highly complex and ritualistic. By comparison, the three-coin method is much simpler and less demanding on materials, but it doesn’t yield the same probability distribution as that in the yarrow stalk method (as to which number gets more chance to be generated). The following table is adapted from Wikipedia. (I’ll explain what the numbers 6-8-9-7 mean in the next post.)

| Number | yarrow-stalk probability | three-coin probability |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1/16 | 2/16 |

| 8 | 7/16 | 6/16 |

| 9 | 3/16 | 2/16 |

| 7 | 5/16 | 6/16 |

In the oldest I Ching documents (such as the Confucian commentaries) only the yarrow stalk method is mentioned, but in fact both methods have been in frequent use throughout Chinese history. There are also improved coin methods that yield the same distribution of probabilities as that in the yarrow stalk method, such as the two-coin method, but those aren’t used as widely as the three-coin method.

Based on the probability difference, some people say that the yarrow stalk method promotes yang or positive energy (e.g., action, imagination, creativity, strength) over yin or negative energy, while no such promotion exists in the three-coin method. But there are also people who suggest that the probability difference isn’t that big a deal if one believes in the I Ching philosophy that nothing is truly random, because probability theory is only relevant when “the events in question are random.”

Whichever method one chooses to use, the goal of the trick is to impose some agency or subjectivity on the moment. The random number–generating activity, as well as the will of the person who performs it, once initiated, becomes part of the moment. And the random numbers thus generated form a channel to “deduce” the bigger picture—via the I Ching hexagrams.

2.↩ Note that Zhouyi is not the only or original version of I. However, with the two alternative and older versions, Lianshan yi ‘changes of linked mountains’ and Guicang yi ‘changes of returning to the hidden’ lost in pre-Zhou history (Wikipedia says Guicang was rediscovered in 1993), Zhouyi became the only surviving version of the book. According to this website the three versions of I “contemplate the universe from slightly different angles.”

3.↩ The higher-dimension talk here isn't just rhetorical. There has been much interest in the mathematics behind I Ching and, among others, a view that the I Ching system is essentially a six-dimensional coordinate system.

Leave a comment