In the previous post I introduced the structural components of I Ching divination, including lines (or monograms), trigrams, and hexagrams. In this and the next post I’ll write about how those components are interpreted. Two posts are dedicated to this topic because result interpretation is the most complex part of I Ching divination. Impatient readers can jump to the summary.

Hexagram level

Interpretation of I Ching divination results traditionally starts from the hexagram level. This is also the easiest level for beginners, because one simply needs to look up a hexagram in the book and read it. For example, the two hexagrams in the previous post are respectively called wei chi ‘before completion’ (未濟 ䷿) and sun ‘decrease’ (損 ䷨).1 The status quo of the questioner’s concern is in “before completion” and its future development is in “decrease.”

Reading through the respective chapters in the I Ching (i.e., Chapter 64 and Chapter 41), we find the following judgments:2

wei chi: Before completion. Success. But if the little fox, after nearly completing the crossing, gets his tail in the water, there is nothing that would further.

sun: Decrease combined with sincerity brings about supreme good fortune without blame. One may be persevering in this. It furthers one to undertake something. How is this to be carried out? One may use two small bowls for the sacrifice.

As we can see, the judgments are quite abstruse and filled with metaphors. This is not a translation issue, as the original Chinese texts are equally (if not more) abstruse. That’s why ancient Confucian scholars insisted that the book be read together with their commentaries, which they named the Ten Wings (十翼)—without which readers of the I Ching could not “fly” high.

Abstruse as they are, the central messages in the two judgments are clear enough. Neither the present nor the future situation of the questioner’s concern is perfectly auspicious, though both are still largely positive. According to Wilhelm/Baynes, wei chi advises the questioner to take extra deliberation and caution for the time being, and sun advises him to draw on inner strength to compensate for what he lacks on the outside in the future. (Just to clarify, I didn’t sort yarrow stalks or throw coins to get the example hexagrams, nor did I ask any question, so this “result” is purely expository.)

Trigram level

A hexagram is made up of two trigrams, and hexagram names are often referenced jointly with their constituent trigrams’ names—or more exactly with the trigrams’ names in their archetypal category—such as “fire-water wei chi” (火水未濟 ☲☵䷿) and “mountain-lake sun” (山澤損 ☶☱䷨), meaning that the archetypal image of wei chi is fire-over-water and that of sun is mountain-over-lake.

The interpretation of a trigram is determined by two factors: its intrinsic meaning and its position in the ambient hexagram. The latter is easier to elucidate, so I’ll begin with it.

(NB: The trigrams discussed here are all primary trigrams. In this introductory text I abstract away from the widely used yet controversial nuclear trigrams. Check this page for the controversy if you can read Chinese.)

Slot meaning

The two trigram slots in a hexagram have their “slot meanings” independent of the specific trigrams inserted there. The most obvious slot meaning is the basic configuration that the upper trigram is above the lower trigram. This is often interpreted in combination with the momentum (i.e., upward or downward movement) of the archetypal elements denoted by the trigrams.

For example, in the hexagram ䷋ (p’i ‘standstill’ 否) the heaven (☰) is above the earth (☷). Albeit natural, this isn’t a good thing in the I Ching system, because it means the heaven’s energy (which goes upward) and the earth’s energy (which goes downward) are moving away from each other, depriving the world of creativity and leaving it in stagnation.

There’s another, more abstract way to view the two trigram slots, in which the upper trigram is called the outer trigram and the lower trigram is called the inner trigram. The inner trigram represents the essence, foundation, or internal conditions of a situation, while the outer trigram represents the environment the situation is embedded in or its external conditions.

For example, the hexagram ䷄ (hsü ‘waiting’ 需) has water (☵) on the outside and heaven (☰) on the inside. This means the questioner is internally strong but externally stuck in a difficult environment, so the best thing for him to do is wait, as the name of the hexagram suggests.

Intrinsic meaning

Compared to their slot meanings, the trigrams’ intrinsic meanings are a lot more difficult to pin down—so difficult that people often just give out a list of specialized meanings when asked. For example:

☰ ch’ien (乾): heaven; creativity; father; horse; head…

☱ tui (兌): lake; openness; third daughter; sheep; mouth…

☶ kên (艮): mountain; standstill; youngest son; dog; hand…

— summarized from Discussion of the Trigrams

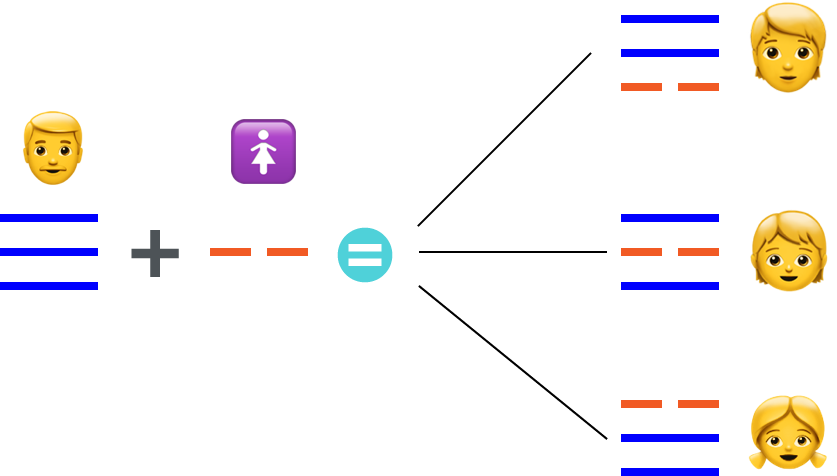

Discussion of the Trigrams (i.e., the Confucian Eighth Wing) deals with the various concepts the eight trigrams can represent in multitudinous categories (nature, animal, family, etc.). Certain trigram concepts share a core meaning; for instance, heaven, creativity, and father all have creative power in Chinese philosophy. But apparently this core meaning interpretation isn’t universally applicable. For example, it’s unclear what the conceptual correlation between lake and third daughter is. In fact the meaning “third daughter” is derived based on a particular way to perceive the trigram—the male (☰) seeks the power of the female (⚋) and receives a daughter at the third time (☱).😝 By analogy, ☴ (sun ‘the Gentle’ 巽) can mean the eldest daughter and ☲ (li ‘the Clinging’ 離) can mean the middle daughter.

So, if there is any across-the-board rule governing the intrinsic meanings of trigrams at all, it is probably the “boring” fact that each trigram symbol, when combined with a category, produces a more or less idiosyncratic concept. I will come back to this point in Part 6).

The above rule in itself doesn’t sound very helpful, because we still need to learn the numerous concepts associated with each trigram one by one. But the good news is that in the actual usage of the trigrams, at least when they are used for divination purposes,3 we seldom need to consider the trigrams’ specialized meanings. Most of the time knowing their archetypal meanings is enough, such as heaven and its creativity, lake and its openness, and so on.

Back to our initial example, the two component trigrams in wei chi (䷿) are li ‘the Clinging’ (離 ☲) and k’an ‘the Abysmal’ (坎 ☵), which respectively stand for fire and water in their archetypal category. Since fire and water move in different directions in nature, in this configuration they are doomed to part company, hence the following interpretation:

Fire flares upward, water flows downward; hence there is no completion. If one were to attempt to force completion, harm would result. Therefore one must separate things in order to unite them.

2.↩ Each chapter in the I Ching consists of four parts: the hexagram, the name of the hexagram (together with the names of its trigram constituents), an overall “judgment” for the hexagram, and separate statements for individual lines (which are only meant to be used for changing lines).

3.↩ Besides divination, the I Ching trigrams are used for many other purposes, such as feng shui examination, qigong design, matchmaking, and event planning.

Leave a comment