The original motivation for this article was an occasional idea about the similarity between I Ching divination and transformational-generative grammar. I ended up using four out of the total six posts to introduce the I Ching because I wanted to present a fuller picture of its content and philosophy before comparing it with something apparently orthogonal to it in the public’s eyes (aka science vs. superstition). I hope that reading has been fun—that is, if you haven’t skipped the previous posts. But if you have, I hope you’ll enjoy this one and the next.😃

Quick links: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6

Transformational-generative grammar

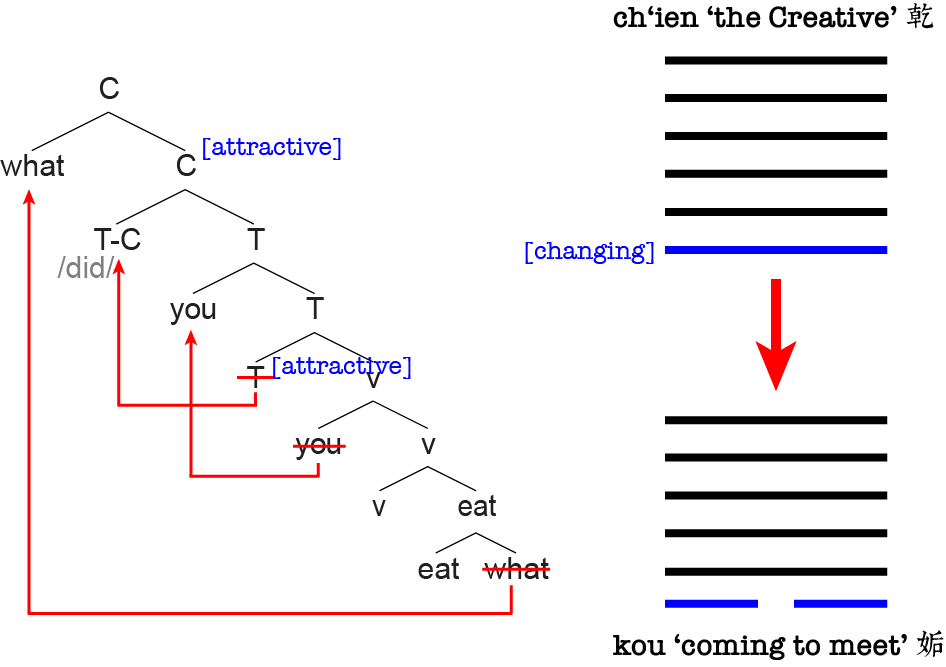

Transformational-generative grammar, or simply generative grammar/syntax as it’s more commonly called today (despite the inaccuracy), is a linguistic theory put forward by Noam Chomsky in the 1960s. It has become a mainstream theoretical school in linguistics (especially in the study of syntax) since then as well as gone through several major shifts (currently in the shape of “minimalism”), though the basic idea hasn’t changed that much—both the earliest “standard theory” and the latest minimalism derive sentences by building up hierarchical structures and manipulating them via form-changing operations (i.e., transformations). For example, to derive the English sentence What did you eat? a generative syntactician would

- postulate a set of ground terms (either concrete or abstract),

- combine them into a hierarchically organized complex term step by step (Chomsky insists on binary combination), and

- do something to that complex term along the way.

Step 1: [eat what]

Step 2: [v [eat what]]

Step 3: [you [v [eat what]]]

...

Step m: [C [T [you [v [eat what]]]]]

...

Step n: [what [T-C [you [

...

Final product: what did you eat

This process is “transformational” in the sense that the initially assembled structure (e.g., step m) is substantially different from the post-manipulation structure (e.g., step n); the former is closer to the understood form while the latter is closer to the pronounced form. The two structures used to be called “deep” and “surface” structures respectively but I guess nowadays no one uses those terms anymore, at least not in the spotlight.

Syntax and semantics

A first similarity between transformational-generative grammar and I Ching divination is that they both separate syntax from semantics. By syntax I mean term manipulation, such as concatenating them into a string or stacking them into a pile, and by semantics I mean the interpretation of syntactically manipulated objects.

The syntactic objects in linguistics are ground terms and bracketed hierarchical structures like those above, while those in I Ching divination are lines, trigrams, and hexagrams. In linguistics every syntactic stage (i.e., every step in the derivation) has a semantic interpretation, either complete or partial. Similarly, every structural level in I Ching divination has a corresponding interpretation.

Example The derivation stage [eat what] has an incomplete predicate-argument interpretation (i.e., an event of eating something); it’s incomplete in that the eater is unspecified. Similarly, ☰ has an intrinsic meaning of ‘heaven; strength’, which is incomplete in that its upper/lower position is not yet specified (not until the whole hexagram is derived).

In linguistics the meaning of a sentence is built from meanings of its parts (this is known as the principle of compositionality); in I Ching the overall meaning of a hexagram can be deduced from meanings of its structural components. The latter isn’t strictly compositional due to its divinatory nature, but the strategy is similar.

Example The meaning of the syntactic object [eat what] is built from the meanings of eat and what, and the meaning of the hexagram ䷅ (sung ‘conflict’ 訟) is largely deducible from the meanings of ☰ ‘heaven; strength’ and ☵ ‘water; danger, guile’—someone who is cunning inside and strong outside tends to be quarrelsome according to the Confucian commentators.

Derivation and transformation

In both transformational-generative grammar and I Ching divination complex terms are derived from simple ones in two ways: combination and transformation.

In current transformational-generative grammar the combinatorial operation is called “merge,” which takes two syntactic objects at a time and joins them together.

merge(eat, what) = [eat what]

merge(v, [eat what]) = [v [eat what]]

...

In I Ching divination, on the other hand, individual lines are stacked on top of one another. Since this operation always increases the existing stack by one, it may as well be treated as a binary operation similar to the push operation in programming languages.

push(⚊, []) = [⚊]

push(⚋, [⚊]) = [⚍]

push(⚋, [⚍]) = [☳]

...

Transformation is the operation that distinguishes transformational-generative grammar from other grammatical theories and I Ching divination from other divination methods. Moreover, in both fields the transformation procedure is triggered by properties on ground terms—namely, lexical items in linguistics and lines in divination. In linguistics the distinctive properties of lexical items are called features; similarly, we can treat properties on I Ching lines as their “features” (more on this later).

Example The functional keyword C in some English clauses bears a transformation feature—let’s call it [attractive]—which draws other words—for example, the question word what and the keyword T (which by the way also bears a transformation feature)—from deeper down in the structure up to its own level, hence the inverted word order. Similarly, in I Ching divination we can assume each changing line bears a transformation feature—call it [changing]—which converts the line to its opposite gender (e.g., ䷀ with a changing first line becomes ䷫).

Categories

Both transformational-generative grammar and I Ching divination make heavy use of categories, and the categorial disciplines of the two systems have a number of similarities, two of which came to my mind immediately when I was preparing for the article, respectively regarding category formation and decomposition.

Example Every natural language word belongs to at least one category; for example, dog is typically a noun and run a verb. Every I Ching symbol (hexagram, trigram, or line) defines a category of patterns or situations in the world; for example, the above-mentioned ䷀ (ch’ien ‘the Creative’ 乾) represents those highly powerful and creative situations (as it consists of purely yang energy).

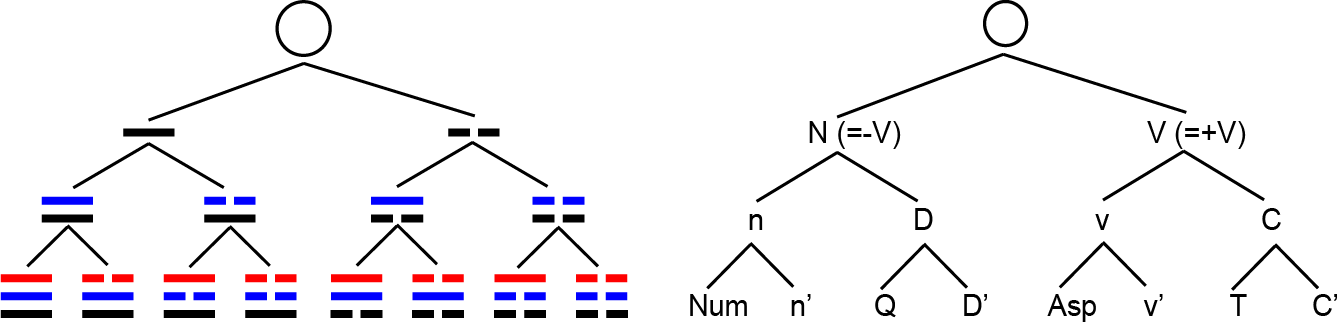

Category division

Categories in both generative grammar and I Ching divination can be given a binary tree organization, where a broadest category is divided again and again into increasingly detailed subcategories. This in a sense reveals how an entire category inventory can be formed from scratch. I have presented the tree of I Ching categories in Part 2. Below I put it next to a similar tree of syntactic categories adapted from a paper by my PhD supervisors (I use the big circle on top to represent the initial, undivided category space).

I guess the parallelism above isn’t that exciting a discovery, because binary division is probably just how category formation works in the human mind in general, so it’s no wonder that the same pattern shows up again and again in different domains of knowledge imagined by humans.

Categorization

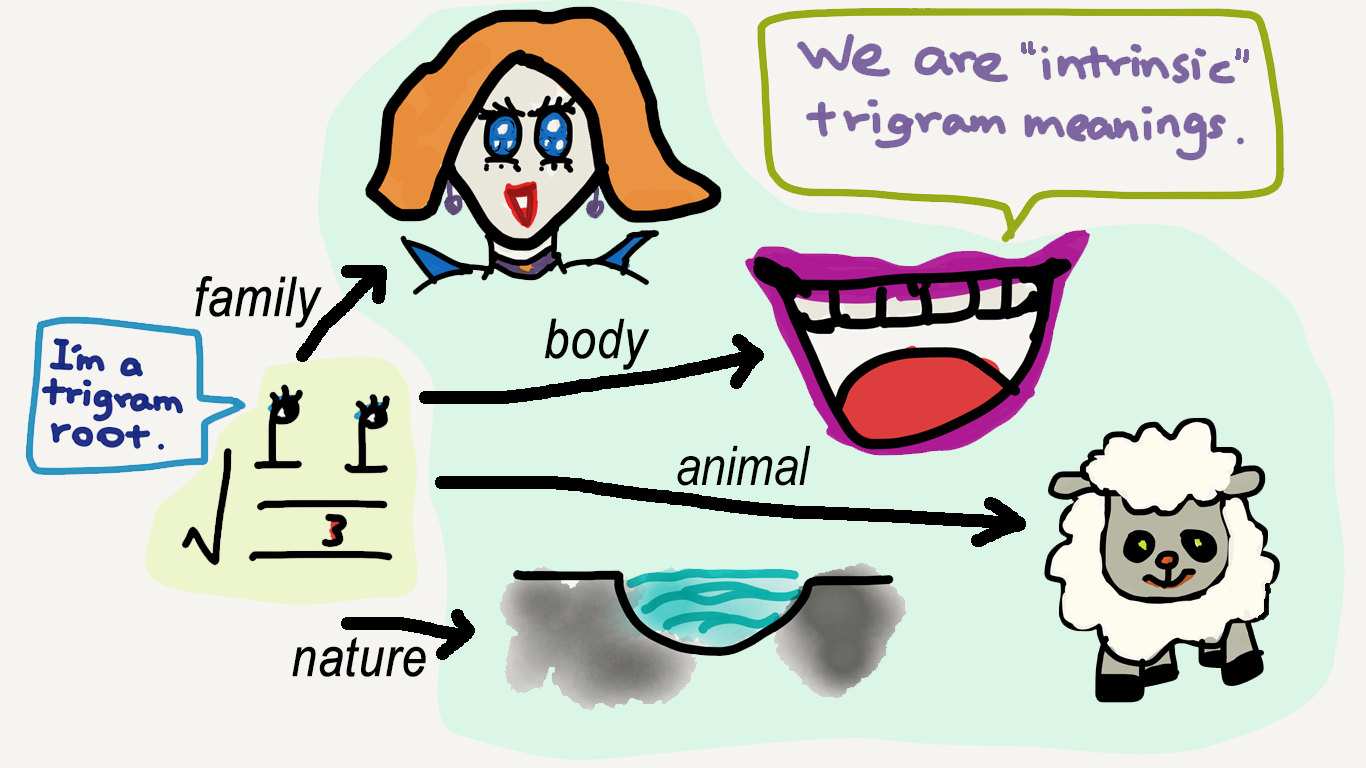

Another parallelism between the categorial discipline of transformational-generative grammar and that of I Ching divination, which I find more special, concerns the intrinsic meanings of trigrams. I first mentioned this in Part 3: the eight trigrams in the I Ching have been associated with numerous meanings in numerous categories, but none of the specialized meanings of a trigram is a perfect candidate as its semantic core.

Example While the “lake” and “openness” meanings of ☱ tui (兌) are conceptually related (a lake is an open area), neither is related to its “third daughter” meaning.

I concluded in Part 3 that the shared core of the multiple meanings of a trigram is none other than the trigram itself—namely, the visual form—detached from any concrete concept. This is reminiscent of a popular trend in transformational-generative grammar, especially in its distributed morphology branch, where words like dog and flower are not taken to be combinatorial atoms but assumed to have a derived status instead. They are derived from two more basic types of unit—a categorial keyword (e.g., noun, verb) plus a category-neutral “root.” The root part is void of any concrete meaning (or pronunciation, for that matter) and only gets concretized via a special process called “categorization.”

Example In distributed morphology dog (the animal) is derived by combining a nominal categorizer n with the root √DOG; the same root can be combined with a verbal categorizer v and yield a verb (as in he is dogged by bad health). It just so happens that in English words sharing a single root often have the same form (hence the traditional term zero derivation), but there are also languages where roots get distinct forms in distinct categories, such as katab ‘he wrote’ and miktab ‘letter’ in Hebrew, whose shared root is k-t-b (the general phenomenon is called root and pattern morphology).

Abstracting away from obvious differences (such as the fact that a linguistic root does define some sort of core meaning, albeit very vague), it feels like the trigram forms in the I Ching are just roots of a certain kind—maybe we can call them visual roots—and a specialized trigram meaning is derived by combining such a root with a particular categorizer (such as nature or animal).

Example The trigram root √☱ has no meaning of its own; it comes to mean “lake” when being combined with the categorizer nature and “third daughter” when being combined with the categorizer family, which in turn define two intrinsic meanings for the trigram.

categorize(√DOG, n) = dog (the quadruped)

categorize(√DOG, v) = dog (the unpleasant action)

categorize(√☱, nature) = lake

categorize(√☱, family) = third daughter

The categorization of linguistic roots is verbally-conceptually based; for example, the root √DOG encodes the concept underlying both the quadruped dog and the unpleasant action to dog. The underlying concept is highly nebulous or downright ineffable, but it has to be there, or we wouldn’t be able to feel the conceptual connection between the two senses of the word form dog.

By contrast, the categorization of trigram roots isn’t based on verbal concepts (or at least that’s not a major factor at play), so the intrinsic meanings of a trigram needn’t share a core concept. That’s why a trigram root can link meanings as disparate as “lake” and “third daughter” together, which is not possible with linguistic roots.

Note that the above distinction doesn’t make the parallelism between linguistic roots and trigram roots less real. It’s just that linguistics and I Ching divination are two totally different fields after all, and so one shouldn’t expect their components to work in exactly the same way.🤷♂️

Also, I said above that each I Ching symbol was a category. That doesn’t contradict my idea here that trigrams are categoryless roots, because these are two distinct perspectives and “category” is an extremely broad notion. Each trigram is a category in the sense that it groups a number of situations or patterns together, but those situations and patterns are precisely the intrinsic meanings of the trigram, which in turn are derived by combining the trigram root with the relevant categorizers.

So, a trigram-qua-category is actually the category of all categorized meanings of a trigram-qua-root; in other words, the trigram-qua-category and the trigram-qua-root define each other. We may therefore treat them as two sides of the same coin—all we need to beware of is that the “category” in trigram-qua-category and that in “categoryless root” aren’t one and the same sort of category. What in the human world isn’t a category after all?🌝

(Check out my PhD dissertation if you’re really into categories.)

Leave a comment