I began my previous post “Where is language from? (Part 1)” by commenting on a recent online article about the origin of language. Then I went on to compare existing views on the origin of human language, ending up with the somewhat pessimistic conclusion that the whole field is still sort of a speculation game. In this post I’ll continue to write about an alleged “language gene,” FOXP2, which has been made popular in recent years.

FOXP2

One aspect of the speculation game in which we are indeed doing better than our nineteenth-century precursors is that we have more versatile devices now, which allow us to obtain more accurate data. Thus, a genetically centered speculation about language evolution is only possible in our times—such as that of FOXP2, the so-called language gene. (I already mentioned it in an earlier post.)

The excitement surrounding FOXP2 is that if this gene really turns out to be “essential for the normal development of speech and language” as the U.S. National Library of Medicine website describes it, then it may provide real evidence that could potentially settle the continuity vs. noncontinuity (or gradualist vs. suddenist) debate once and for all—we just need to examine the evolution of the gene.

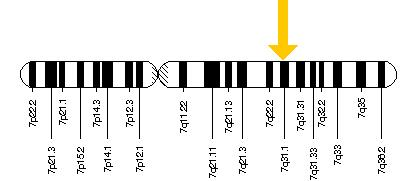

FOXP2 is a transcription factor that instructs the formation of the forehead box P2 protein. It has been dubbed the language gene because alterations in it can cause severe developmental speech disorders. There are multiple types of FOXP2 alteration, such as

- a total deletion of it,

- a mutation within it,

- a translocation in its ambient chromosome, and

- two copies of it inherited from a single parent (the mother).

Whatever the alteration type is, a person with FOXP2-related speech disorder is afflicted with articulation difficulty since young, which is known as childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). Following is a pedagogical video from Mayo Clinic.

Note that while FOXP2 mutation can cause CAS, not all cases of CAS are caused by FOXP2 mutation. The total prevalence of apraxia is about 1–2 in 1,000 people, and FOXP2-caused cases only take up a small portion of it. In fact the original discovery of the gene at the beginning of this century was based on just two cases: the well-known KE family and a separate patient CS.

Language gene or not?

Although FOXP2 has made its name as the first gene directly linked to speech and language disorders, there is much skepticism about its publicized role—especially among linguists but also from experts in other fields.

FOXP2 cannot be regarded as “the” gene “for” language, since it is only one of many that have to be functioning properly to permit its normal expression.

— Bolhuis et al. (2014)

So is FOXP2 “the language gene”? No serious scholar now makes that claim. … Its role in language is at best indirect, and many other genes are relevant to the normal maturation of language in humans.

— Carstairs-McCarthy (2017)

Not only the role of FOXP2 in language development but also its evolutionary path has been questioned. Allegedly recent genomic analyses have overturned the earlier conclusion that the gene had undergone positive evolutionary selection in humans. Besides, a fact that the general public don’t necessarily know (or aren’t always told) is that FOXP2 isn’t unique to humans but has been found in many other species as well, including birds, mice, chimpanzees, and our evolutionary cousin, the Neanderthals. What’s more, fossil studies reveal that the Neanderthal version of FOXP2 is actually the same as the human version, which means either that we are not the only chattering homo or that our current understanding of the gene’s relation to language is flawed.

Also, as a transcription factor, FOXP2 actually regulates hundreds of genes, not all of which are relevant to language (Wikipedia says it is expressed in the brain, heart, lungs, and digestive system). In fact, even the authors of the original FOXP2 paper (Lai, Fisher, Hurst, Vargha-Khadem & Monaco 2001) have disagreements as to which aspects of human language the gene really affects. Vargha-Khadem contends that it merely governs the mechanical aspect of language but not the cognitive aspect. This mechanics-only take on FOXP2 converges with what Berwick and Chomsky wrote in their MIT monograph:

FOXP2 is more akin to the blueprint that aids in the construction of a properly functioning input-output system for a computer, like its printer, rather than the construction of the computer’s central processor itself. … [W]hat has gone wrong in the affected KE family members is thus something awry with the externalization system, the “printer,” not the central language faculty itself.

— Why Only Us, p.77

So, promising as the FOXP2 story may sound—and it certainly isn’t a hoax—there’s still a long way to go before any substantive conclusion can be drawn about its role in the origin of human language. In my opinion, what FOXP2 offers twenty-first-century scientists is a beginning instead of an end, and the questions it forces us to think about are more valuable than the disputes it may (not) resolve.

A romantic view

What fascinates me the most about the origin of language is that since no one can really convince anyone on the issue, neither can anyone disdain anyone else. Everyone is just guessing, and everything is possible. So, it’s okay to believe in the weirdest theory (even weirder than that of Wurruri!) or go all out for religion, which offered men the first systematic explanation of the world after all.

An article I’d like to mention at this point is “The origin and evolution of language: a plausible, strong-AI account” (Hobbs 2006), which I came across while working on this post. I find the article refreshing because it leaves the continuity vs. noncontinuity debate aside for the most part and pursues a logico-computational route instead, whereby the author explores how the intentional and neurophysiological levels of language can be bridged via intermediate mappings.

The central metaphor of cognitive science, “The brain is a computer,” gives us hope. Prior to the computer metaphor, we had no idea of what could possibly be the bridge between beliefs and ion transport. Now we have an idea.

— Hobbs (2006), p.48

I’m not in a position to evaluate the scientific (de)merits of the article. What I like about it is its open-mindedness towards ideas from competing theoretical schools. For instance, the author’s adoption of a unification grammar, which is at odds with Chomsky’s syntactic theory (which is transformational), doesn’t stop him from praising language universals like Chomsky’s Universal Grammar as “the strongest argument” for the position that fully modern language was already in the possession of the earliest homo sapiens. I think this kind of open attitude is something that everyone in the speculation game can benefit from.

Perhaps it’ll eventually turn out that our language capacity is indeed a gift from God (or from the Flying Spaghetti Monster for that matter). We may even all be descendants of aliens, in which case it’s simply futile trying to find an origin for our language by scrutinizing animal fossils on this planet. I’m fine with any storyline, be it “scientific” or not. I may even write poems about the different possibilities to show what a romantic soul I have. Life is beautiful!

Leave a comment