In this part I continue to share my personal impressions of 19th-century Chinese language textbooks. I’ll finish off my review of Marshman’s book and then start reviewing Morrison’s book.

1. Elements of Chinese Grammar (continued)

Syntax part

Rating: ★★★✦✧☆

I have mixed feelings about the syntax part of Marshman’s textbook. It certainly has an impressively comprehensive coverage of function words, including auxiliary verbs, prepositions, final particles, and so forth. For instance, in the section on degree comparative expressions the author makes the following remark, which I quite agree to and don’t find pompous at all.

I have reason to think, that there is scarcely any mode of expressing comparison used either in respectable works, or in correct conversation, which will not co-incide [sic] with some one of the examples given. (Elements, p.295)

Many pros

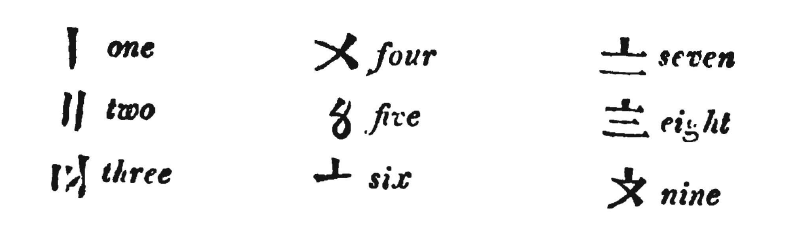

Then, in the section on numerals, Marshman surprisingly gives out names of some very large numbers (e.g., 京 jing1 ‘ten million’, 垓 gai1 ‘a hundred million’) that are seldom if ever taught in modern textbooks. He also gives a detailed introduction of the three parallel numerical systems used for different purposes (I think only two of them are still in use now). I have to admit that I hadn’t even heard of the third system. 😅

I can’t exhaust the positive notes I made while reading the syntax part of the textbook. For example, I also highly liked the section on pronouns (p.322 ff.), where numerous attested pronouns are listed, be they “standard” or not. And I was even more impressed by Marshman’s explanation of the 82 classifiers he had found in Classical and Early Modern Chinese (p.501 ff.). Besides, as a linguist I am more than sympathetic to the Marshman’s repeated stress on the multifunctionality or categorial underspecification of Chinese characters. It is indeed remarkable that he had thought about this, and in quite accurate terms, more than two centuries ago, considering it’s still a hot research topic as of 2020.

A second mode [of part-of-speech formation] is that of the Hebrew … in which an idea is expressed by a root … which … in its original state, is most commonly a verb, but which in numerous instances is also used as a noun [or] an adverb …. Chinese … evidently carries the principle farther than any other language. (Elements, pp.195–196)

In thus tracing the various ways in which the Chinese express the degrees of comparison, it is easy to perceive that the same principle pervades this part of their grammar, [namely,] that of causing certain characters used occasionally as verbs … to drop all idea of time as well as of mood and person, and to perform the humble office of comparative particles. (Elements, pp.295–296)

Some cons

The above said, however, there do also exist a couple things in the syntax part of Marshman’s textbook that I dislike. First off, Marshman mixes examples from written and spoken Chinese but doesn’t always tell readers which Chinese variety his particular examples are from. This may mislead foreign students.

Note: Up till early 20th century, the spoken language and the (official) written language in China were in fact two separate language varieties. People spoke Early Modern Chinese (16th–19th centuries) but wrote in mid-to-late Old Chinese (8th–3th centuries B.C.E.), aka Classical Chinese (文言文).

Second, Marshman tries to squash Chinese into the Indo-European grammatical framework and frequently confuses formal and conceptual concepts. For instance, in the section entitled “Of the tenses” he writes:

In the standard writings of the Chinese are to be traced Five Tenses evidently distinct from each other; the Aorist, the Present tense, the Perfect, the Past connected with time, and the Future. (Elements, p.431)

Statements like this make Chinese sound akin to European languages, when in fact “tenses” in the former and those in the latter are totally different things. In order not to mislead the uninitiated, I think the author should have made it clear that he was merely using “tense” (and other similar Indo-European terms) for Chinese on a conceptual level—there are tense-like concepts in the language, of course, as in every other human language, but there are no formal tools to mark them, nor do they play any role in syntactic rules. But okay, such a strict distinction between semantics and syntax might be too futuristic for a 19th-century textbook. 😅

Third, I’ve come across quite a few “Indo-European-supremacist” remarks in the syntax part of the book. For instance, the author described European languages as more “cultivated” several times (e.g., on p.371) and once also termed inflectional languages like Sanskrit and Greek as “highly polished” (p.405). This probably was part of the general atmosphere back in early 19th century, but considering the book is still influential now (e.g., it has a 2013 new edition), I worry that it may accidentally (re)sow discrimination among linguistically inexperienced readers.

Based on the above pros and cons, I give the syntax part of Marshman’s textbook three and a half stars out of five. And this brings us to a moderate overall rating for the book 👉

2. A Grammar of the Chinese Language

The second 19-century Chinese textbook I’d like to review is Robert Morrison’s (1815) A Grammar of the Chinese Language, henceforth Grammar, which is called 通用漢言之法 in Chinese. Morrison was also a British missionary and the publication time of the book was also in the 1810s. Yet it has a quite different style from Marshman’s book. For one thing, it’s only half as thick. For another, it has a totally different goal.

The object of the following work is, to afford practical assistance to the student of Chinese. All theoretical disquisition respecting the nature of the language has been purposely omitted. (Grammar, Preface)

Unlike Elements, which went rather deep into the theoretical and historical aspects of the Chinese language, this book was only (and proudly) meant to be a practical guide. Probably due to this more mundane goal, Morrison chose to teach colloquial instead of Classical Chinese, even though the latter was the official written language of the time and sociopolitically indispensable.

Morrison’s textbook also consists of three main parts—one on characters, one on pronunciation, and one on syntax—though their boundaries are not very clearly demarcated. Also, it puts the pronunciation part before the character part (unlike in Marshman’s book). Below I’ll give each part a rating and some personal remarks. This section is much shorter than the previous one because I don’t have as much to say. 😅

Robert Morrison (1782–1834) was in fact a contemporary of Joshua Marshman. He worked as a Protestant missionary to Macao and Canton. Judging by information on the Internet, he was a lot more notable than Marshman, but I must say his Chinese textbook isn’t as good in all three parts. His multivolume Chinese-English dictionary, on the other hand, is truly impressive, so maybe he was more of a lexicographer than a grammarian? 🧐

Both Morrison’s textbook and his dictionary are available online.

Pronunciation part

Rating: ★✦✧☆☆☆

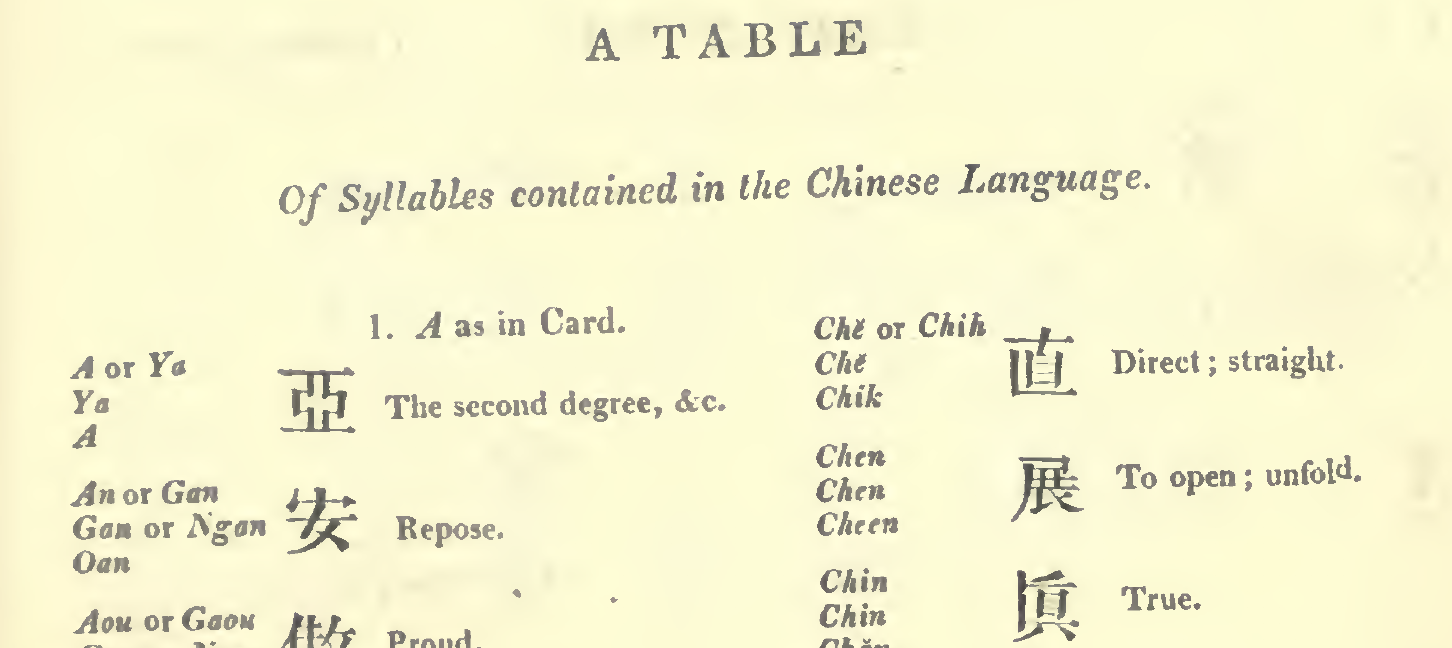

Morrison uses 24 pages to teach pronunciation, but half of them are actually occupied by a huge table that lists all the syllables in the language (from A to Z!). He not only illustrates each syllable by a representative character but also provides Cantonese pronunciations alongside Mandarin ones.

To be honest, I don’t see the point of putting such an exhaustive table of examples in the main text of a textbook—students most likely won’t have the patience to go through it. Putting myself in a beginner’s shoes, I expect the pronunciation part of an introductory textbook (of any language) to cover the following questions:

- How many consonants/vowels are there in the language?

- How to pronounce each consonant/vowel (ideally with IPA or at least in comparison with a language I know, say English)?

- What special pronunciation rules (such as intonation rules) are there in the language?

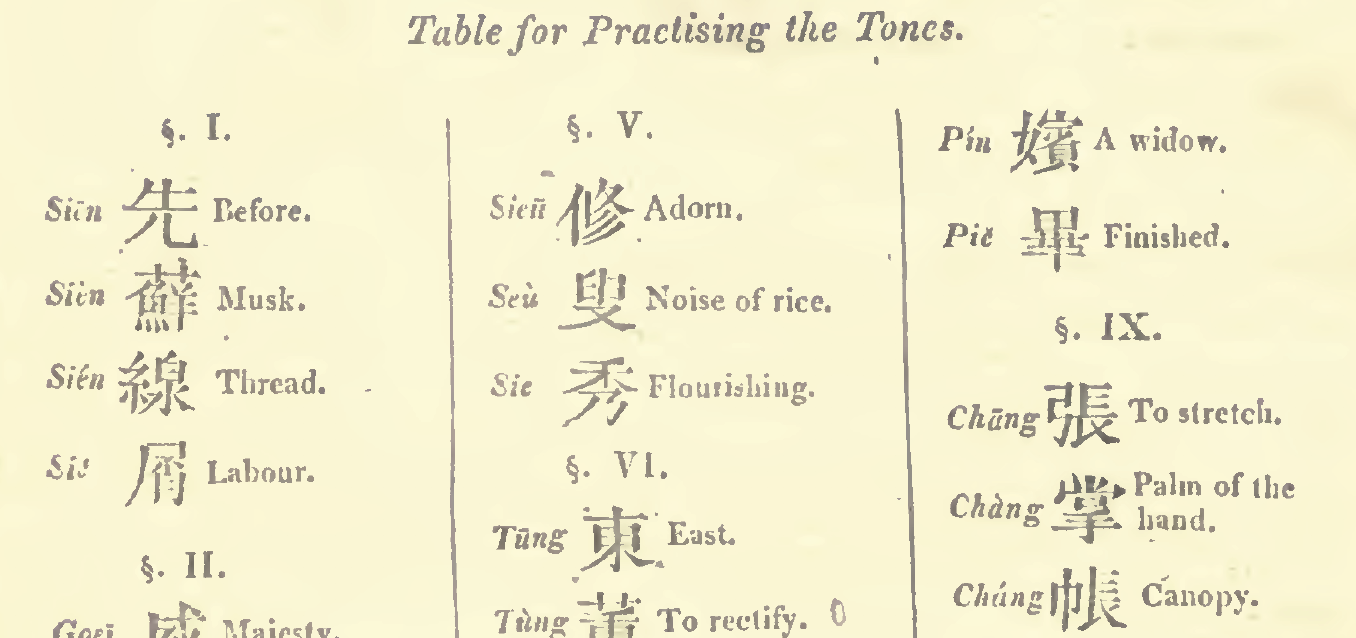

While these questions are dealt with in almost every foreign language textbook today (e.g., Routledge’s Colloquial series) and also all tackled in Marshman’s book, in Morrison’s book we can only find partial answers to the second and third questions. So, instead of listing all the syllables of the language—which I really think should be in an appendix rather than the main text—perhaps the author should have provided a list of Chinese phonemes (i.e., consonants and vowels) instead. The book does have a dedicated section on tones, but again the explanation is rather cursory, and again quite some space is occupied by a long table (for tone practice).

Overall, I don’t think the pronunciation part of Morrison’s book is suitable for people who are learning the language on their own, but maybe it wasn’t intended for self-study in the first place, for the author does mention the need of an instructor several times.

To each syllable [in the table] is affixed an [sic] useful character, that the learner in acquiring the pronunciation may avail himself of the assistance of the mere Chinese Scholar. (Grammar, p.3)

The pronunciation of the Tones can only be learned from a living Instructor. (Grammar, p.21)

Character part

Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

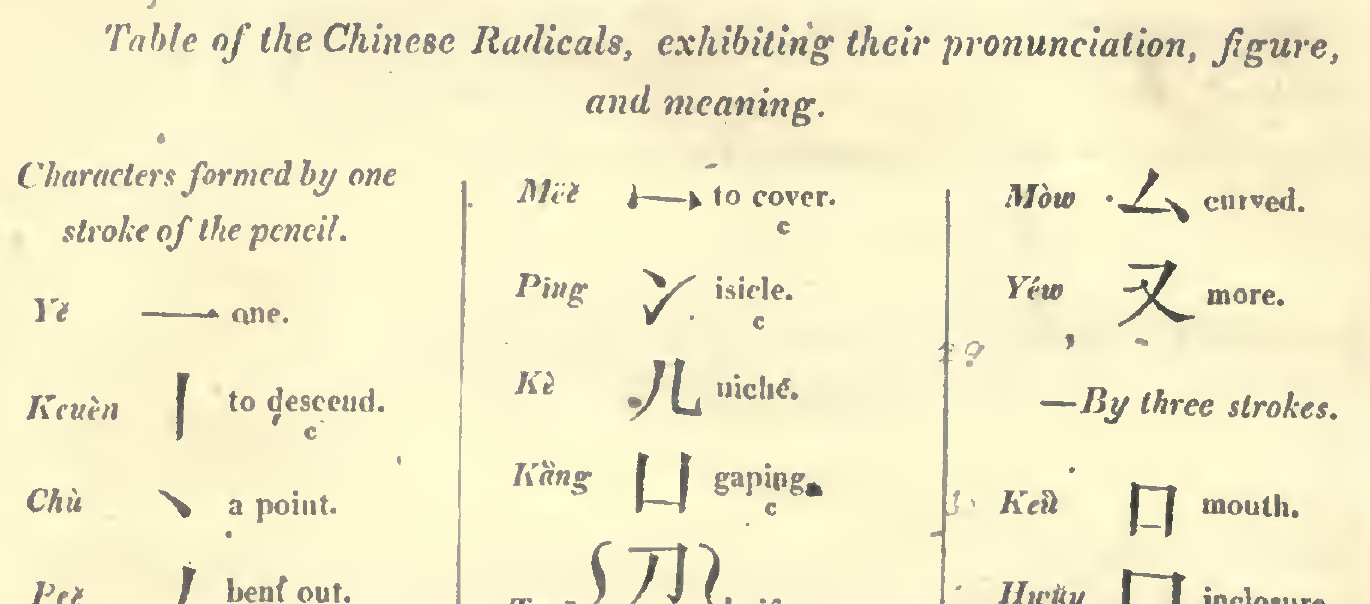

The character part of Morrison’s book is also very short, with only 11 pages. And half of those pages are yet again occupied by a huge table—this time by one of the 214 radicals. I won’t complain about that since a similar table is also contained in Marshman’s book, which simply means that character learning was considered a very important part of Chinese learning in the 19th century—perhaps even more so than grammar learning.

There’s an old Chinese saying, 讀書百遍其義自見, which says that if you read a book (i.e., a Classical Chinese work) for a hundred times its meaning will automatically become clear to you. This is probably not scientifically true, but it’s indeed how children used to acquire the written language back in the long history of imperial China—via extensive reading 📚. However, the only prerequisite that a pupil did have to obtain from a teacher first was knowledge of the characters (or at least the theory of their formation), without which there was no way to start the reading-a-hundred-times process. I guess this is partly the reason why character learning was deemed so important in the past. 🀄️

One thing about Chinese characters that’s mentioned in Morrison’s book (albeit only in passing) but not in Marshman’s book is how to hold an ink brush (p.25), which Morrison for some reason called a “hair pencil” 💇♀️✏️—a term that sounds like a word-for-word translation from Chinese mao2 bi3 (毛筆). But since Morrison’s character part is very cursorily written and doesn’t teach the character formation principles at all after teaching the radicals, I wouldn’t recommend this part to Chinese learners either.

Leave a comment