This is the third part of this long post. In this part I’ll present my remaining review for Morrison’s book and then turn to Wade’s seminal work.

2. A Grammar of the Chinese Language (continued)

Syntax part

Rating: ✦✧☆☆☆☆

As aforementioned, Morrison mainly teaches colloquial instead of Classical Chinese in his textbook. This is most clearly reflected in the syntax part, where most if not all examples as well as the grammatical points they illustrate are colloquial in nature. 🗣

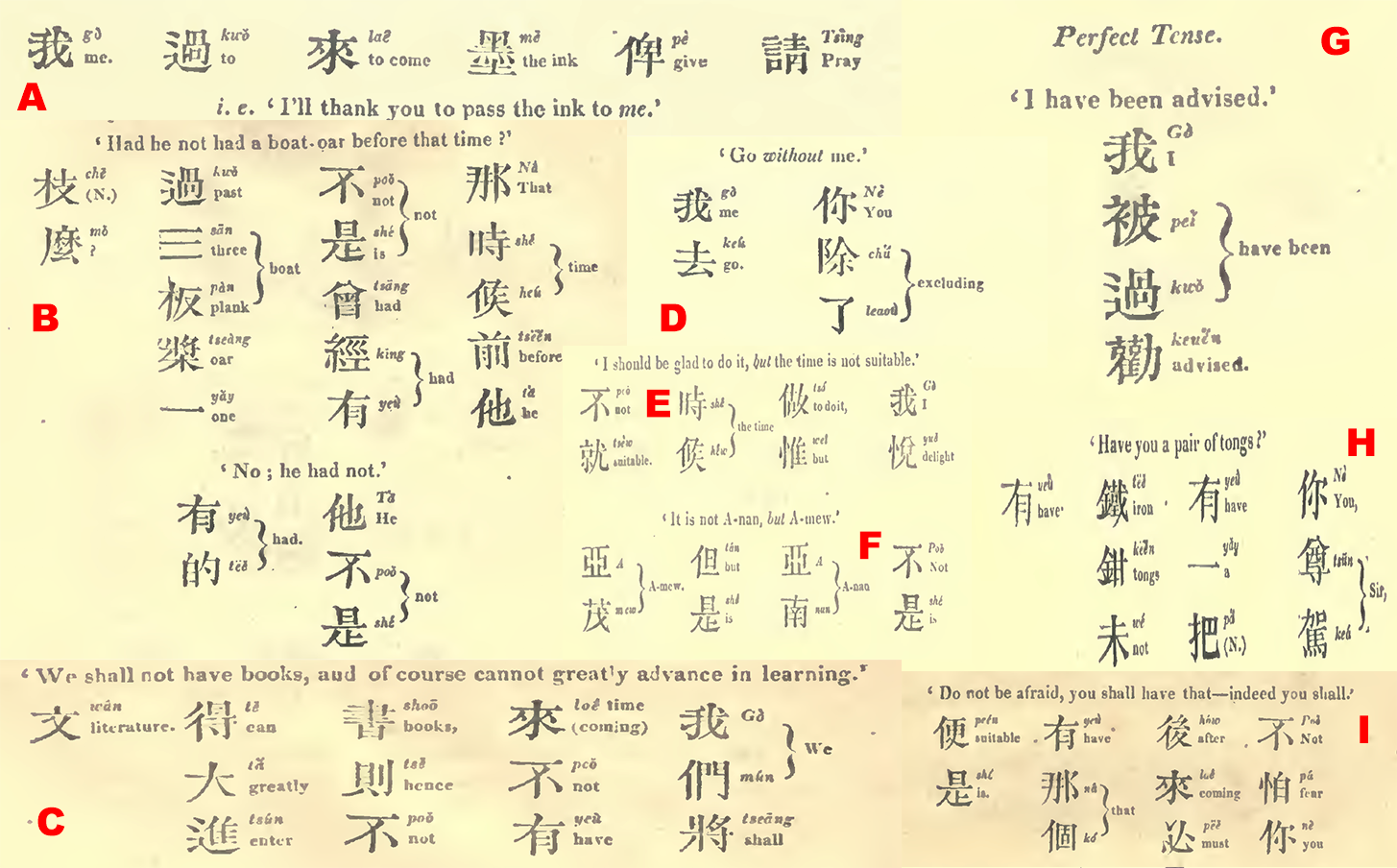

There’s no problem with that for sure—if anything it makes Morrison’s textbook in principle a great supplement to most other contemporaneous textbooks—but unfortunately many example sentences in the book are actually wrong, and some of them are so badly formulated that I can’t even parse them without looking at the English translations. The picture below shows a selected few of the problematic examples in Morrison’s book.

Bad examples

Below I show the bizarreness of these sentences by mimicking their problematic syntax in English. The “Intended” sentences (in blue) are what Morrison wanted to say, and the “Actual” sentences (in red) are what the Chinese sentences actually sound like.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

A. 請俾墨來過我。(p.88)

Intended: Please pass the ink to me.

Actual: Please give ink to pass me.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

B. – 那時候前他不是曾經有過三板槳一枝麼?

– 他不是有的。(p.120)

Intended: – Had he not had a boat oar before that time?

– No, he had not.

Actual: – Had he not had boat oar a in front of that moment?

– No, he is not some.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

C. 我們將來不有書則不得大進文。(p.122)

Intended: We shall not have books, and of course cannot greatly advance in learning.

Actual: If we will not having books in the future then we cannot get great advance learning.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

D. 你除了我去。(p.234)

Intended: Go without me!

Actual: You removed me go.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

E. 我悅做惟時候不就。(p.255)

Intended: I should be glad to do it, but the time is not suitable.

Actual: I happy do it, solo the moment not just.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

F. 不是亞南但是亞茂。(p.255)

Intended: It is not A-nan, but A-mew.

Actual: Is not A-nan, however A-mew.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

G. 我被過勸。(p.192)

Intended: I have been advised.

Actual: I have been-ed advise.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

H. 你尊駕有一把鐵鉗未有?(p.114)

Intended: Sir, have you got a pair of tongs?

Actual: Have you Sir got a pair of tongs ne have?

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

I. 不怕你後來必有那個便是。(p.123)

Intended: Don’t fear. You’ll have that in the future—indeed you will.

Actual: Not fear. You must have had that after that time—just yes.

☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙☙

Due to the large number of problematic examples, the syntax part of Morrison’s book can be highly misleading. Also, the bizarre feeling I got from the above sentences is not due to the fact that I’m a 21st-century person looking at 19th-century sentences. On the one hand, two centuries isn’t really that long in the history of the Chinese language, and grammatical changes within such a short period of time are practically nothing to a Chinese reader’s eyes. On the other hand, I’ve read plenty of literary works (e.g., novels, plays) from the 16th–19th centuries (which form part of high school education in China) but haven’t seen any writer producing sentences like those in Morrison’s book. Indeed, I don’t remember feeling “non-Chinese” at all, so to speak, when I read Early Modern Chinese works as a teenager.

So, in terms of example selection, I prefer Marshman’s methodology, because he had only taken examples from authentic, time-honored Classical Chinese works:

In a language cultivated with care for many ages … there must exist a certain fixed mode of expression, which is considered as the standard of style …. This standard is to be found in those works which the Chinese have for so many ages regarded as models of style. It is by examples from these works, given in their original character, that I shall endeavour to exemplify the various peculiarities of Chinese grammar. (Elements, pp.189–190)

Morrison could have done the same thing. Even though the official written language in China at his time was Classical Chinese, there were plenty of literary works written in colloquial Chinese too (such as those I read in high school). Yes, those works were deemed vulgar by Classical Chinese writers, but they nevertheless were a valuable source of linguistic examples.

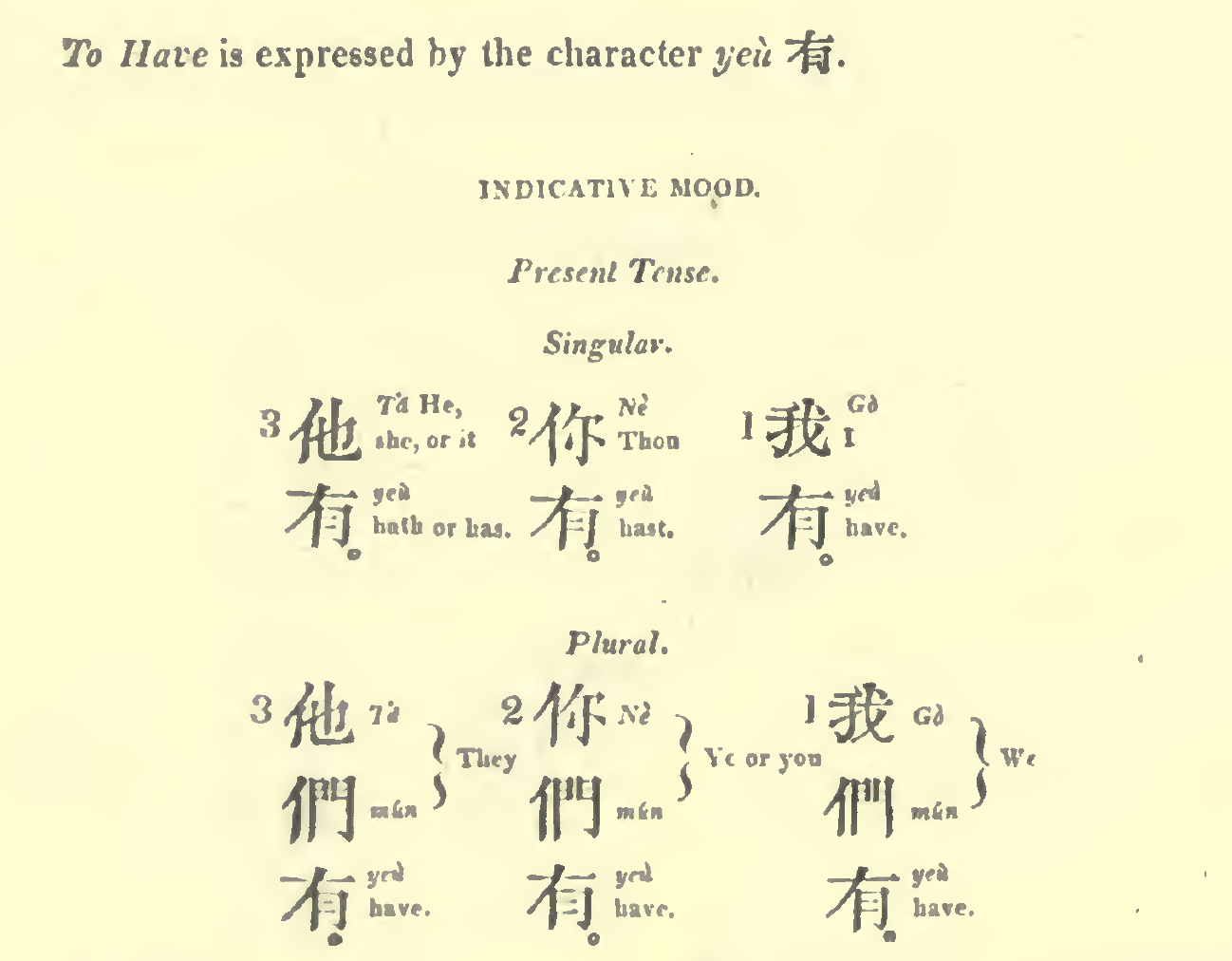

I’m not the only one who finds Morrison’s examples odd. For instance, I’ve noticed the following comment on the Douban page for the book:

And I’ve noticed the following comment in another 19th-century sinologist’s book (which isn’t a textbook but a handbook):

Dr. Morrison’s Chinese Grammar … contains some valuable matter, but from the haste with which it appears to have been prepared for publication, and from the fact of its having been published at so early a period after Dr. Morrison’s entrance upon the study, the student must not expect to derive much positively practical advantage from its perusal. (Summers 1863, A Handbook of the Chinese Language, Preface)

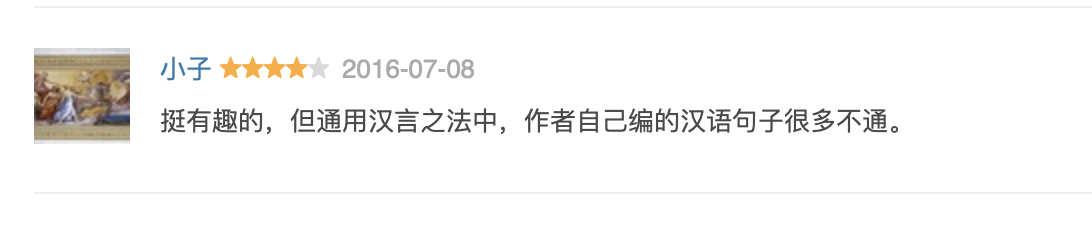

Forced paradigms

Apart from the ungrammatical examples, another aspect of the syntax part of Morrison’s book that I don’t particularly like is its procrustean imposition of the Indo-European system on Chinese. Morrison had not only painstakingly (and often wrongly) squashed Chinese grammar into Indo-European categories (e.g., gender, number, mood) but also taken a further step and applied the Indo-European inflectional paradigms to Chinese! 🤯 Of course, this is just repeating the same word form again and again, since Chinese isn’t an inflectional language.

Due to the highly problematic nature of its syntax part as well as the uninformativeness of its pronunciation and character parts, I don’t recommend Morrison’s textbook to Chinese learners at all. And my overall rating for it is 👉

3. A Progressive Course of Colloquial Chinese

The third 19th-century Chinese textbook I’d like to review is the famous Yuyan Zi’er Ji (語言自邇集) by Thomas Francis Wade (1867), or Yü-yen Tzŭ-êrh Chi in the romanization system invented by the author (i.e., the immensely influential Wade-Giles romanization system). Since the English name of the book is too long (see below), I’ve truncated it a bit to A Progress Course of Colloquial Chinese, henceforth Progressive.

Full title: A Progressive Course Designed to Assist the Student of Colloquial Chinese as Spoken in the Capital and the Metropolitan Department 😝

Overall structure

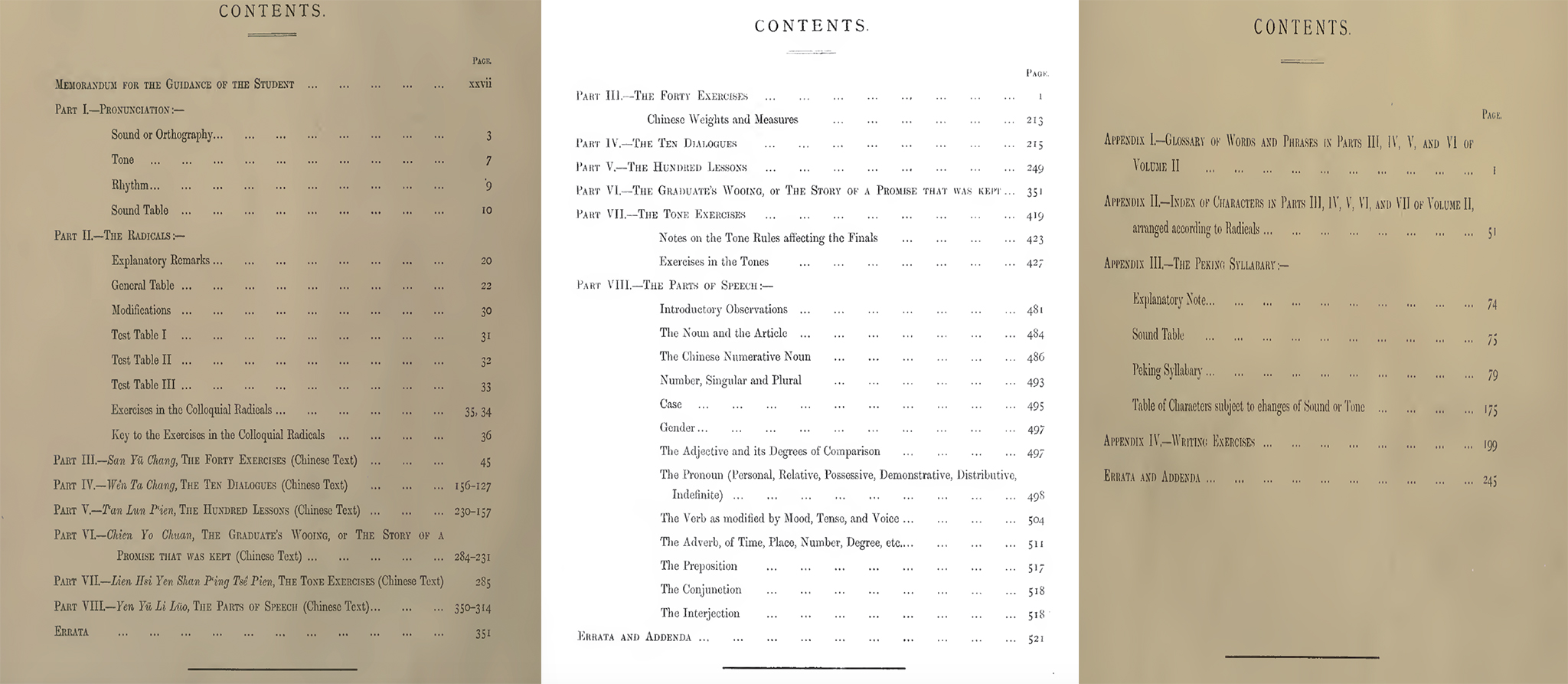

Rating: ★★★☆☆

While the previous two textbooks both consist of just one volume, Wade’s textbook consists of three volumes. Volume I has a part on pronunciation, a part on radicals, and the Chinese texts for all the grammatical lessons (from the third part on). No English translations or explanations are provided whatsoever—those can only be found in Volume II. In addition, Volume II also contains all the grammatical notes. Thus, I guess one could fairly say that the actual textbook in Wade’s “trilogy” is the second volume, while the first and third volumes are just two book-length appendices. Volume III, by the way, is a collection of glossaries and other similar tables of reference.

I don’t understand why Wade had decided to separate the Chinese texts and their English explanations, or the exercises and their keys, in two volumes. It’s not like a single book containing both components would be too thick or anything. Even if we keep the repeated Chinese texts (i.e., those in the third part) and all the front and back matters, the total number of pages in Volumes I & II is still well under 1000.

Due to its popularity, Wade’s textbook was reprinted multiple times. This review is based on the second edition from 1886, because it is the edition whose three volumes are all freely available online 👇

Links (2nd ed.): Vol. I, Vol. II, Vol. III

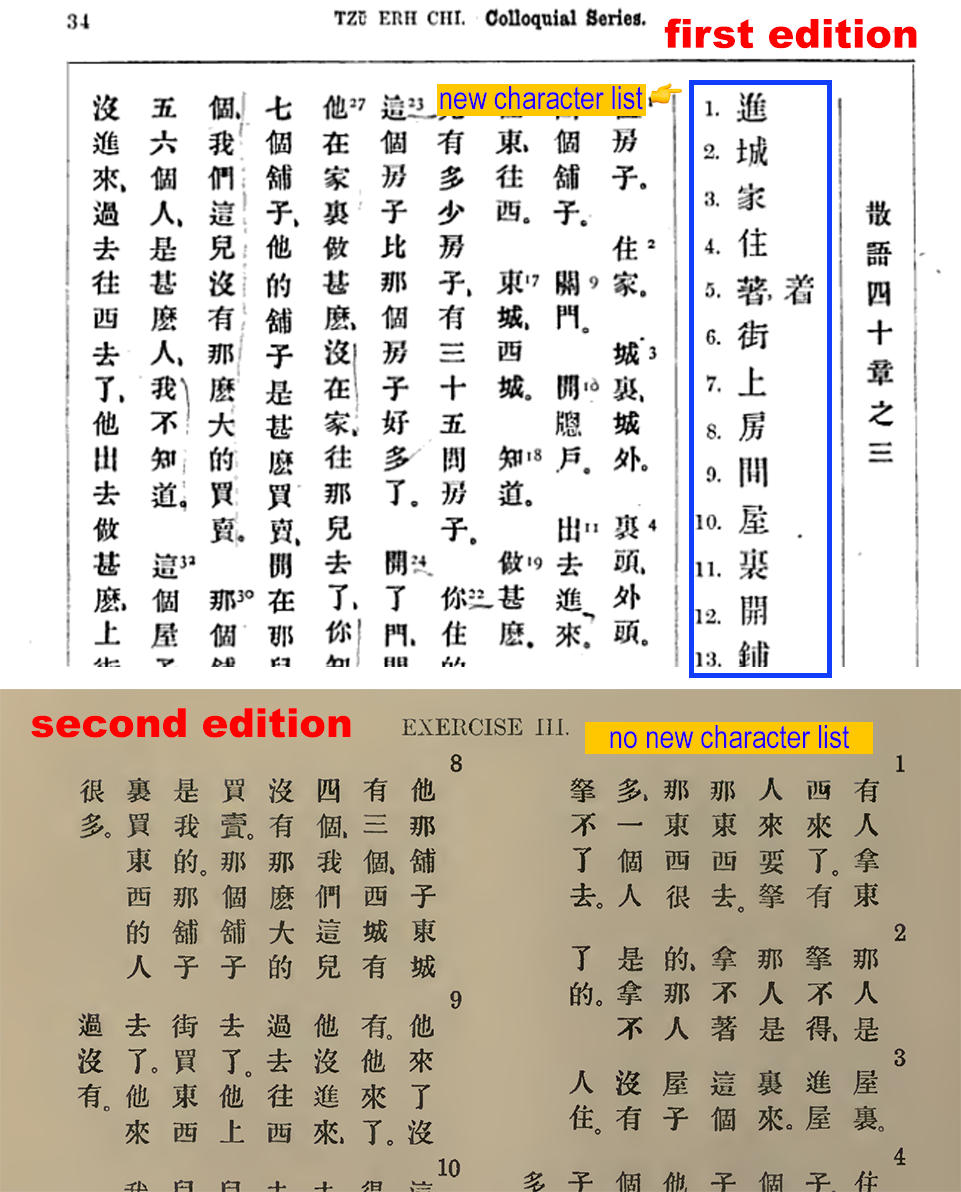

That said, I actually quite like the page layout in the first edition, because it has the traditional Chinese typographical style and also has a new character list accompanying each lesson in the third part. It’s a shame that the author had decided to remove them in the second edition. Yes, those lists can still be found in Volume III, but the new design is much less user-friendly, for students must now carry all three books or at least two of them to the classroom for grammar lessons. 🎒😧

Despite my dissatisfaction with the volume organization of Wade’s textbook, I still give its structure three stars considering its comprehensiveness.

Pronunciation part

Rating: ★★★★✦✧

The pronunciation part of Wade’s textbook, namely the first chapter of the first volume, is essentially a user guide for his romanization system. It explains the pronunciation of each Mandarin Chinese phoneme in crystal-clear terms and in comparison with familiar European languages like English, Italian, French, and German. For example, when teaching the vowel ü Wade writes:

When uttered alone, as it is at times for yü, or when a final, nearest the vowel-sound in the French eût, tu. In ün it is not so long as in the French une; but nearer the ün in the German München. (Progressive, Vol. I, p.4)

Attention to details

Wade is very good at clarifying pronunciation details. For example, when teaching the vowel ê (e in pinyin, [ɤ] in IPA), he writes:

Nearest approached in [British] English by the vowel-sound in earth, in perch, or in any word where e is followed by r, and a consonant not r; as in lurk. (Progressive, Vol. I, p.3)

Here Wade had carefully chosen only English words where the vowel is /ɜː/ instead of the schwa /ə/ (e.g., about, ago, again) because the Chinese ê is neither as short nor as light as the schwa.

Of course, for certain (difficult) phonemes Wade’s explanations aren’t quite accurate—such as his description of the diphthong ou (also ou in pinyin, [ou̯] in IPA) as similar to the English ou in round and loud (ibid., p.4) and his description of the consonant hs (x in pinyin, [ɕ] in IPA) as “a slight aspirate preceding and modifying the sibilant” (p.5)—but other than such occasional glitches I’ve found Wade’s phonetic descriptions both accurate and easy to follow.

Tones and aspiration

In addition to the careful and detailed phonetic descriptions, another thing about Wade’s pronunciation part that I appreciate is his repeated emphasis on the importance of tones and aspiration. In his own words:

The full recognition of the aspirate’s value is of the last importance; the tones themselves are not of more. A speaker who says kan when he ought to say khan might as well speak of Loudon for London. (Progressive, Vol. I, p.7)

Tones.—There is no subject on which it is more important to write, and none on which it is harder to avoid repeating what has been said by others. (ibid.)

Wade also explains why he had chosen the “inverted comma” (more exactly the spiritus asper but in practice often typeset as the left single quote) instead of an h to mark aspirated consonants:

… lest the English reader, following his own laws of spelling, should be led to pronounce ph as in triumph, th as in mouth … which would be a serious error. (ibid.)

Thus, in Wade’s romanization system 平 ‘flat, even’ is transcribed as p‘ing2 instead of phing2, and 歎 ‘exclaim, sigh’ is transcribed as t‘an4 instead of than4. In fact, since Wade was already using superscripts to mark tones, he could have used them to mark aspiration as well, as in standard IPA [phing] and [than]—but of course IPA had yet to be invented back in 1867!

Also, although Wade had considered his “inverted comma” notation for aspiration both well-chosen and indispensable, its actual usage gradually became messy in the later spreading of the romanization system, with the aspiration symbol (as well as the tones) often being left out for aesthetic reasons, as in place names like Tsingtao (靑島) and Taipei (臺北), which more precisely should be transcribed as Ts‘ing1-tao3 and T‘ai2-pei3.

However, since such sloppy usage is not Wade’s fault, and since the pronunciation part in his textbook is generally quite laudable (except for the aforementioned tiny glitches), I’d happily give it four and a half stars. 👍

P.S. Like Morrison, Wade gives a huge table for tone practice in his textbook (pp.10–17). However, I won’t complain about that or let it affect my rating because, unlike Morrison, Wade also gives plenty of explanatory text besides the table.

Leave a comment