In Part 3 I finished reviewing Morrison’s textbook and also began reviewing Wade’s textbook. In this part I’ll continue to comment on the character and the syntax part of Wade’s book.

3 - A Progressive Course of Colloquial Chinese (continued)

Character part

Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

The character part of Wade’s textbook (Part II, Vol. I) is far less informative than its pronunciation part. It only contains a two-page introduction of Chinese characters, about 3/4 of which is on how to look them up in dictionaries and how to use the subsequent tables and tests. The remaining 1/4 isn’t satisfactory either, for it basically tells readers that all Chinese characters have a phonosemantic structure, when in fact phonosemantic characters make up just one of the six character types.

[T]he written character [is] made up of two parts, its Radical, and that part which is not its Radical. The latter part various sinologues have for fairly sufficient reasons agreed to term its Phonetic. (Progressive, Vol I, p.20)

Compare the above description from Wade’s textbook with the following one from Wikipedia:

All Chinese characters are logograms, but several different types can be identified, based on the manner in which they are formed or derived. There are a handful which derive from pictographs (象形) and a number which are ideographic (指事) in origin, including compound ideographs (會意), but the vast majority originated as phonosemantic compounds (形聲). The other categories in the traditional system of classification are rebus or phonetic loan characters (假借) and “derivative cognates” (轉注). (Wikipedia)

While the majority of existing Chinese characters (especially the more specialized ones) are phonosemantic in structure, this doesn’t mean that the other five character types can be ignored, especially in textbooks. In fact, characters for the most fundamental concepts of nature and human life are often not phonosemantic, such as the pictographic 日 ‘sun’ and 月 ‘moon’, the ideographic 一 ‘one’ and 二 ‘two’, the rebus 我 ‘I’ and 來 ‘come’, and so on. By comparison, all chemical element names are recorded by phonosemantic characters, and so are most species names. Perhaps this state of affairs can give readers some hint as to why phonosemantic characters are so abundant.

I’m a bit shocked by the paucity of information in the character part of Wade’s textbook, because the subsequent syntax part actually demands a fairly high level of character proficiency. Not only is everything presented in Chinese from the third part on, but the conversations and texts are all in authentic Beijing Mandarin as well, without any buffer lessons with contrived beginner-level sentences like “My name is Amy” and “Rory is a man.”

Maybe Wade’s intention was that students should not begin Part III before having achieved a good understanding of the character system, but I can hardly see how that achievement can be made from the cursory and misleading introduction plus the radical table in Part II. So, it seems Wade’s textbook is most suitable for a taught program led by a qualified instructor after all, just like Morrison’s textbook. Self-studiers, on the other hand, must either find supplementary materials at the character-learning stage or simply use a different textbook. Well-designed textbooks weren’t easy to lay hands on in the 19th century, of course. 😞

Syntax part

Rating: ★★★★★

Let’s suppose a 19th-century English student had managed to meet the character proficiency threshold set by Wade and was ready to enter Part III, with all three volumes of the textbook laid open on his desk next to his notebook, ink brush, ink stone, etc. He might still be complaining to his classmate about the clutter when the school bell chimed, but after beginning to study the first lesson in Part III he would immediately be enthralled by the perfectly designed texts and the pellucidly written grammatical explanations. He might even find the English-to-Chinese translation exercises tantalizingly brain-teasing!

At least that’s how I felt when I read Part III of Wade’s textbook, though I’m a native Chinese speaker and so my perspective might be biased. Anyway, there are several aspects of the syntax part of Wade’s book that I like a lot and don’t think one can find in either Marshman’s or Morrison’s book.

Content words

First, Wade provides explanations not only for the function words but also for the content words. For example, in the first excerpt below he teaches the Chinese words for “house,” “room,” and “shop” as well as their classifiers (which Wade calls “numeratives”), and in the second excerpt he teaches the three motion verbs “stand,” “recline,” and “sit,” accompanied by some glossed examples and helpful notes on their semantic subtleties (e.g., 走 is necessarily on foot but 走道兒 isn’t).

Variant characters

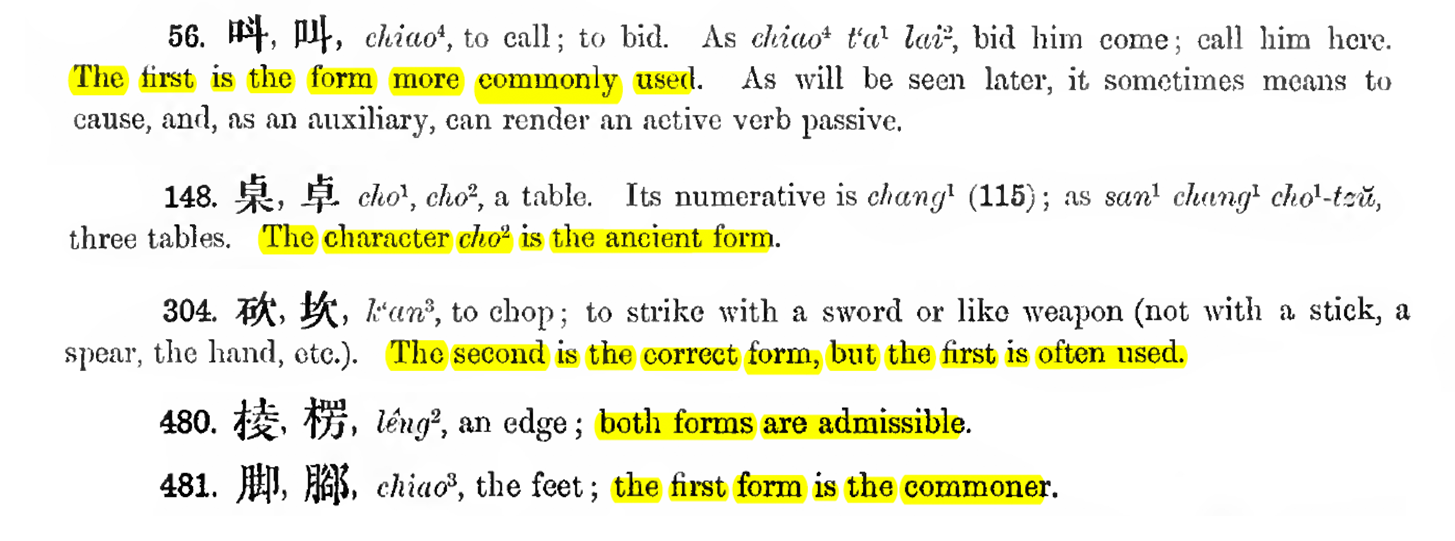

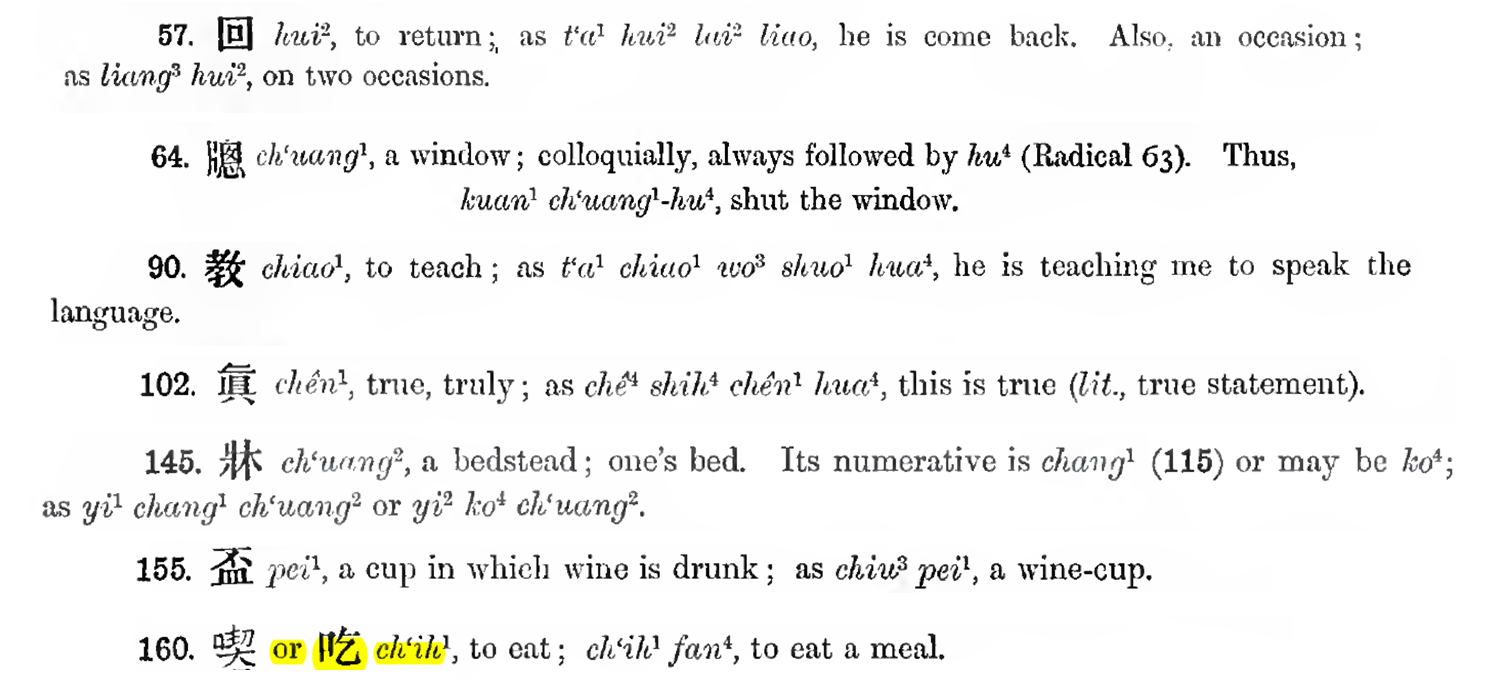

Second, Wade gives variant characters (aka allographs) when they exist and also explains their differences. There used to be many freely interchangeable variant characters in parallel use. Most textbooks nowadays only teach the officially recommended character forms and don’t give allographs at all (though dictionaries still list them), while Marshman’s and Morrison’s books in most cases simply adopt one of the allographs without any comments. However, since allography is an important aspect of the diachronic and synchronic reality of the Chinese writing system, and students will certainly meet them in real life, it’d be very considerate of textbook compilers to include some notes and examples for them.

Admittedly, there are lots of cases where Wade either fails to explain the interallograph differences or don’t list the variant forms for a character at all, as the following excerpts demonstrate. But still, Wade’s textbook is probably the only one I’ve seen that bothers to give students guidance on variant characters. 👍

Teaching via dialogs

Third, Wade teaches syntax (in Part VIII) via a series of dialogs between two linguistically curious people—a Chinese man and an English man who has apparently learned Chinese to an advanced level—like in a TV show 📺. So, instead of directly listing grammatical points as most other textbooks do, Wade lets the two roles converse about them. This style of teaching is both creative and efficient even from a 21st-century perspective. See the excerpt below (on category, syntax, subject, and predicate) for an example:

Chinese text (Progressive, Vol. I, pp.346–347)

👨🏻:我們英國話文限制死些兒,沒有漢字那麼活動。且將英文分兩大端論之:一爲單字,一爲句法。那單字共分九類,是爲單字之一端;至於連字成句、連句成文,那就是句法之一端。

👲:敝國向來作文章,也有分股分段的規矩。閣下剛說這句法,或者是那麼樣罷?

👨🏻:那却不同。貴國作文講究的是句法,專管那個字句的長短;我們成句之理,就是無論何句,必須綱目兩分,方能成句。何爲綱?凡句內所云人、物、事等字眼兒爲綱。何爲目?論人、物、事的是非、有無、動作、承受,這都爲目。

Note: I’ve updated Wade’s Chinese punctuation to the modern style.

English translation (Progressive, Vol. II, pp.483–484)

👨🏻: The limitations of our language are somewhat more inflexible; the terms in it have not the convertibility of terms in Chinese. But now, to come to the English language, let us for the moment separate [its grammar into] two grand divisions, the single words of the language and the laws of sentences. In the one division the single words are referred each to one of nine categories (the Parts of Speech); the other gives the rules by which single words are made into sentences, and sentences into longer sections of composition.

👲: Is the distinction that we observe in Chinese essays between the ku (pairs of sentences even in length) and tuan (odd sentences) at all the same as the chü fa (laws of sentences) of which you have been speaking?

👨🏻: Not the same; in Chinese composition it is the chü fa that is important, and it is to the relative proportions of sentences only that attention has to be paid: our theory is this, it is essential to the constitution of any sentence that it contain kang (a subject) and mu (a predicate). The person, thing, transaction, condition, spoken of, is the subject; the qualifications of the subject, as that it is right or wrong, existent or non-existent, active or passive, form its predicate.

Note: Here and below the notes in square brackets and parentheses are Wade’s.

Even though the dialog style is gradually replaced by a monolog style (and sometimes by a plain textbook style), Wade’s syntax part still reads a lot more natural than Marshman’s and especially Morrison’s, because Wade doesn’t attempt to squash Chinese grammar into an Indo-European mold but merely objectively compares the two systems. For example,

Chinese text (Progressive, Vol. I, p.327)

👨🏻🏫:英國無論人物,所有議及是爲的、是做的、是受的,這宗字樣,都歸爲那九項之一。漢文並沒有這個限制,較難創出個專名子來。就是那活字這字樣,雖不能算是儘對的,權也無不可。容我把兩國隨用的那活字,有相對有相反的地方兒,勉強做個榜樣。

English text (Progressive, Vol. II, p.504)

👨🏻🏫: Words that predicate being, doing, suffering, whether of person or thing, are in English referred to one of the nine categories before mentioned [that of the Verb, to wit]. No such line being drawn in Chinese, and the invention of an equivalent [for the word verb] presenting some difficulty, we shall take on us to employ the term huo tzŭ (live words), which, though incomplete, is unobjectionable, and we shall endeavour, with the reader’s permission, to show by examples the analogies and contrasts of the huo tzŭ as employed under different conditions in both languages.

In my opinion, such an aboveboard recognition that Chinese doesn’t have the kind of verbal category like that in European languages (which inflects for mood, tense, voice, etc.) is much more acceptable and accurate than the quasi inflectional paradigms given in Morrison’s book (see Part 3 for an example).

Authentic colloquial Chinese

Last but not least, the colloquial Chinese in Wade’s textbook feels a lot more authentic than that in Morrison’s textbook, which corroborates my earlier intuition that many of Morrison’s sentences are actually wrong. I especially like Wade’s choices of words. Take the following excerpts from Part V for example.

你看這種賤貨,竟不是個人哪!長得活脫兒的,像他老子一個樣,越瞧越討人嫌。不論是到那兒,兩隻眼睛擠顧擠顧的,任甚麼兒看不見。 (Progressive, Vol. I, p.200)

“Just see what a miserable creature that is; he is not a man at all; he is a beast; the very counterpart of his father; the more one sees of him the more he disgusts one. Wherever he goes he gets into the same scrape; his eyes are so closed up that he can’t see.” (Progressive, Vol. II, p.291)

你怎麼這麼樣兒不穩重?若是體體面面兒坐着,誰說你是木雕泥塑的廢物麼?你若不言不語的,誰說你是啞吧麼?……你自己不覺罷咯,傍邊兒的人都受不得了。多喒遇見一個利害人,喫了虧的時候兒,你纔知道有關係呢。(Progressive, Vol. I, pp.190–191)

“[Elder Brother, to younger.] Why can’t you behave yourself in society? People won’t set you down as having nothing in you because you sit still, as a decent, orderly person should. If you never say a word no one will accuse you of not having the use of your tongue. … You don’t perceive how ill it looks, but it makes all the rest of the company uncomfortable, and one of these days you will fall in with someone who is not to be trifled with, and when you come to grief, you’ll understand the risk you run by this sort of conduct.” (Progressive, Vol. II, p.304)

Reading conversations like the above, I almost feel like I’m back in my hometown in Northern China (and can even envision some relatives of mine uttering them 😝), because they really sound like how modern northerners speak in daily life, even though they appear in a 19th-century book! In particular, phrases like 賤貨 ‘(of a person) miserable creature, bitch’, 擠顧擠顧的 ‘(of eyes) unbeautifully winking all the time (as a bad habit)’, 不言不語的 ‘(of a person) quiet’, and 多喒 ‘when, at what time’ are so colloquial that they actually sound a bit vulgar, and modern textbooks most likely won’t teach them due to their dialectal nature.

A 2017 song by an Internet celebrity whose title contains the vulgar word 賤貨 jian4huo4

Based on the above merits I give the syntax part of Wade’s textbook a five-star rating. And this brings us to the following overall rating for the textbook (counting only the pronunciation, character, and syntax ratings and excluding the overall structure rating to be fair) 👉

Leave a comment