In Part 4 I finished my review of Wade’s textbook and gave it the highest rating among all the 19th-century textbooks I’ve reviewed so far. In this part I’ll turn to the last textbook I’d like to review: von der Gabelentz’s Chinesische Grammatik (in German).

4. Chinesische Grammatik

This textbook (henceforth Chinesische) was written by the German general linguist and sinologist Hans Georg Conon von der Gabelentz (1840–1893) and published in 1881, which makes it the youngest among the four textbooks in this blogpost. Its Chinese title is 漢文經緯 ‘lit. longitude and latitude of the Chinese written language’, which in my opinion is the most grammatical-sounding among all four Chinese titles below:

- 中國言法 Elements of Chinese Grammar

- 通用漢言之法 A Grammar of the Chinese Language

- 語言自邇集 A Progressive Course of Colloquial Chinese

- 漢文經緯 Chinesische Grammatik

Titles 1–3 don’t really make sense to an ordinary Chinese reader. They are understandable with some guesswork (and some peeking at the English titles) but one can easily tell that the authors aren’t native speaker. Title 4, on the other hand, sounds totally natural and appealing, as if it had been given by an erudite traditional Chinese scholar.

Since von der Gabelentz was a linguist, his textbook is a lot more linguistically oriented and so also more accurate in terms of grammatical concepts. Indeed, after reading through the book I feel that a modern linguist can directly take the descriptions in it as the basis for more advanced theoretical analyses.

This textbook is freely available online too. Also, due to its highly technical nature, the author had subsequently published a beginner’s version for it entitled Anfangsgründe der Chinesischen Grammatik ‘Rudiments of the Chinese Grammar’ (1883), henceforth Anfangsgründe, which is again freely available.

My review here is mainly based on the unabridged version, though I’ll include stuff from the beginner’s version from time to time as well because it contains a nice part on colloquial Chinese in addition to the Classical Chinese parts inherited from the unabridged version, which makes von der Gabelentz’s book the only one that teaches both written and spoken Chinese. 👏

Overall structure

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

The unabridged version of von der Gabelentz’s book consists of three major parts: a general introduction part, an “analytical system” part, and a “synthetic system” part.

The general introduction part begins with some general information on the Chinese language, such as its history, its dialects, and its influence in East Asia. After that, the author uses two chapters to teach pronunciation and characters. Both the second and the third part are on Classical Chinese grammar, but the author had separated the grammatical stuff in two parts, respectively calling them the “analytic” and the “synthetic” system. Under the two parts we find the following major topics:

- “Analytic” part:

- relations between adjacent words and morphemes

- usage of function words and morphemes

- determination of word categories (i.e., parts-of-speech)

- “Synthetic” part:

- syntactic constituents

- syntactic patterns

- simple, complex, and subordinate clauses

- stylistics

I don’t really like the author’s analytic vs. synthetic contrast because that means something else in modern linguistics. Nor do I think that contrast makes the presentation of Chinese grammar any clearer, because one can’t really tease apart the word and the sentence level of the grammar, especially considering the author not only writes about words themselves in the “analytic” part but also has quite some discussion on combinatorial relations between words and the determination of word categories, which are at least partly within the realm of syntax.

Exactly due to this interrelatedness of the two levels, the author ends up repeating certain grammatical points several times in the course of the book. For instance, the parts-of-speech are introduced at least three times, twice in the “analytic” part and once in the “synthetic” part, and the interconstituent relations are introduced twice. Such reintroductions may confuse readers and make them wonder “Hasn’t the author already taught this? Why is he teaching it again (and yet again)?”. I constantly had this feeling while reading the second and third parts of the book. 😣

I actually like the chapter organization in the beginner’s version better, which also has two syntax parts: one on the “old language” (i.e., written or Classical Chinese) and the other on the “newer language” (i.e., spoken or Early Modern Chinese). And under the “old language” part we see a simple two-chapter organization covering word classes and sentence constituency.

Due to its unsatisfactory structural organization I give this aspect of von der Gabelentz’s textbook two stars, but that’s fine because this rating won’t be taken into account in the overall rating. 🌝

Pronunciation part

Rating: ★★★★★

Despite my low rating of the overall structure of von der Gabelentz’s (unabridged) textbook, when it comes the detailed content of each individual chapter, I actually find the author’s descriptions and notes surprisingly informative. I give the pronunciation part of von der Gabelentz’s textbook five stars based on the following three reasons.

Entering tone

First and foremost, an absolutely unique thing that von der Gabelentz does in his textbook is that he clearly and precisely marks all the entering-tone characters in his romanization system, even though the entering tone had already vanished from Beijing Mandarin at his time. As for the motivation, he writes:

Es ist zweckmässig, in die Umschreibung die alten Auslaute m, k, t und p mit aufzunehmen. Erstens … erleichtert sich dadurch einerseits das Verständniss der Reime und andererseits die Erlernung anderer Dialecte. Zweitens dürften sich gerade die volllautigeren Formen dem Gedächtnisse bequemer einprägen als die verschliffenen. 日 žit, Sonne, und 入 žip, eintreten, 力 lik, Kraft, und 立 lip, stehen, 心 sīm, Herz, und 新 sīn, neu u. s. w., tragen sozusagen ausgeprägtere Züge als žih, lih, sīn. Nur vergesse man nicht, dass es sich hierbei um blosse Hülfsconstructionen handelt: ausser jenen Schlussconsonanten ist Alles modern. (Chinesische, p.30)

“It is practical to include the old final sounds m, k, t and p in the transcription. First, … both the understanding of the rhymes and the learning of other dialects become easier in that way. Second, the fuller sound forms could just be easier to memorize than the slurred ones. So to speak, 日 žit ‘sun’ and 入 žip ‘enter’, 力 lik ‘strength’ and 立 lip ‘stand’, 心 sīm ‘heart’ and 新 sīn ‘new’, and so on carry more distinctive characteristics than žih, lih, sīn. One should only not forget that what is involved here are merely auxiliary constructions: everything is modern except for these final consonants.”

And on the same page he further explains:

Auslautende, einfache Vocale, mit oder ohne vorhergehendem Halbvocal, werden lang oder doch scharf gesprochen; graphisches k, t, p dagegen zeigt an, dass der vorausgehende Vocal kurz abzubrechen ist, wie im französischen mot, trop. Die Pekinger Mundart hat auch diese Spur der auslautenden mutae verloren.

“Final, simple vowels, with or without a preceding semivowel, is uttered long or rather harsh; the graphic k, t, p, in comparison, indicate that the previous vowel should be broken off short, as in the French mot, trop. The Beijing vernacular has also lost this trace of final changes.”

Conservativeness

Second, von der Gabelentz lists the vowels and consonants of Chinese right at the beginning of his pronunciation part, which is a component that I’ve wanted to see but haven’t seen in the other textbooks. The accompanying pronunciation guide is also pretty straightforward. Overall I get the feeling that von der Gabelentz’s romanization system is a rather conservative one, which tries to preserve many ancient features. The above-mentioned entering tone is just one such feature. Other examples include the diphthong eu (which had become ou in the 19th century), the unpalatalized combinations ki and k’i (which had become tsi/ts’i or či/č’i’ in Beijing Mandarin), the postsibilant in/ing (which had become en/eng), etc. Thus, the following characters are transcribed in a slightly different way from how they are actually pronounced (I provide the actual pronunciations in parentheses in von der Gabelentz’s style):

(1) 頭 t’eû (t’oû), 輕 k’īng (č’īng), 正 číng (čéng)

In accordance with this systematic conservativeness, von der Gabelentz also gives a detailed description of the differences between the phonological system in Kangxi Dictionary (which is basically inherited from Middle Chinese) and that in 19th-century Beijing Mandarin (pp.27–31). This is quite interesting from a linguistic perspective, but again ordinary language learners probably wouldn’t want to go that deep.

Multiple dialects

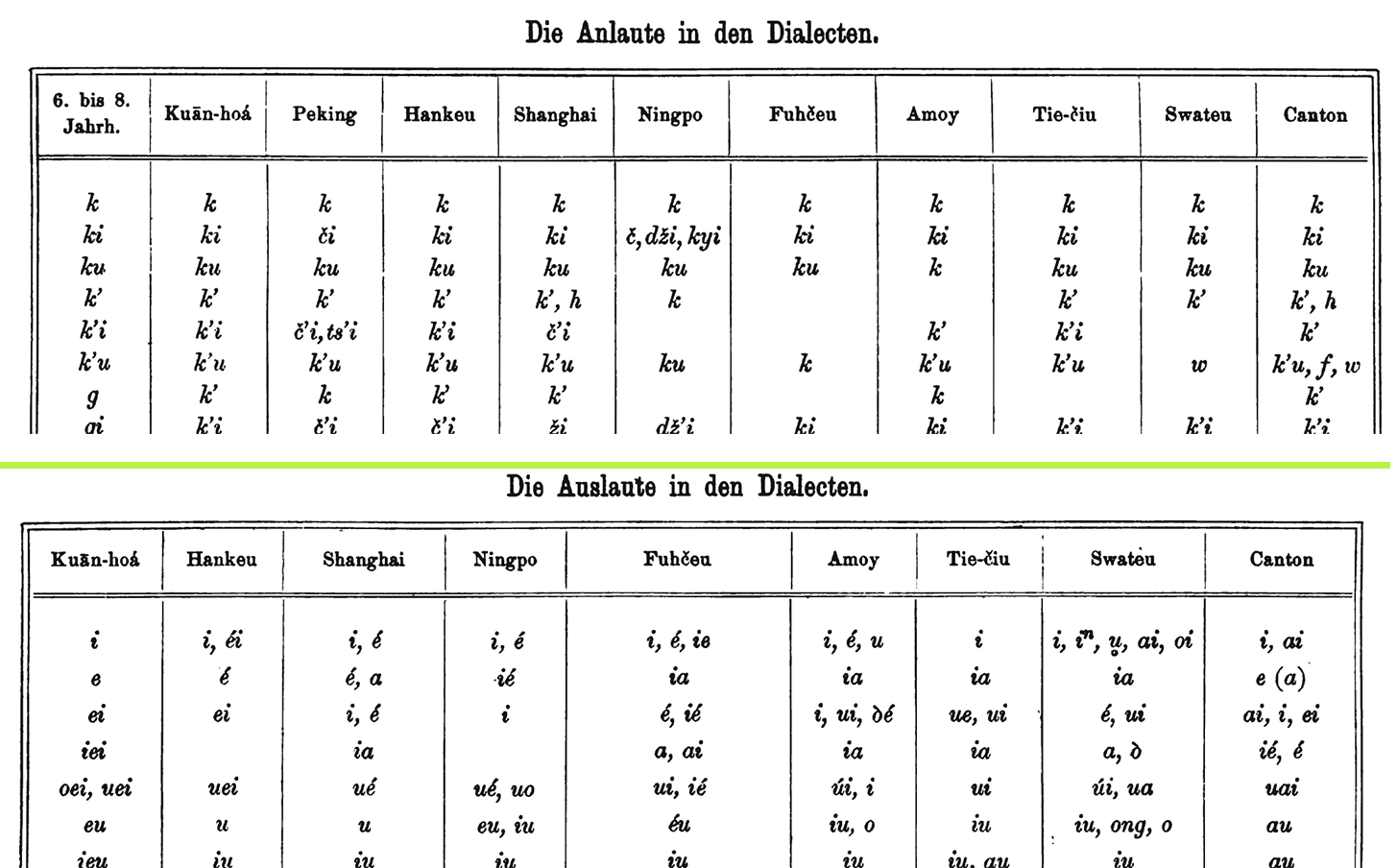

Third, the section on crossdialectal variation in von der Gabelentz’s textbook is also a lot more informative than that in the other textbooks. In particular, it contains two multipage tables presenting the initial and final sound counterparts in some ten dialects.

Character part

Rating: ★★★★✦✧

The character part in von der Gabelentz’s textbook is again surprisingly informative and comprehensive. It covers the following aspects about Chinese characters:

- their history,

- their traditional classification,

- the basic principles of their formation,

- their allography,

- their ordering in historical dictionaries,

- their organization in texts (e.g., punctuation, special typographical rules),

- their calligraphy, and

- their historical usage as phonetic symbols for loan words.

Character statistics

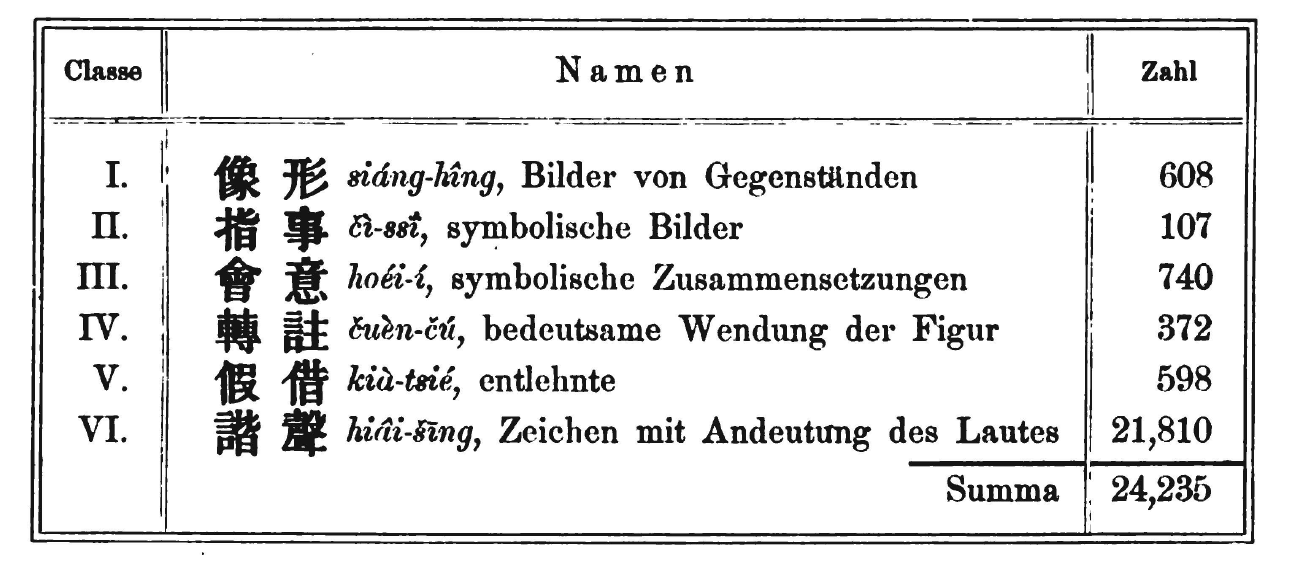

Each of these aspects are accompanied by ample illustration, and again the author pays a lot of attention to the details. For instance, in the section about the traditional classification of characters, he not only lists the class names but also gives a number for each class based on statistics from a certain dictionary, so that readers can get an impression of the relative proportions of the six classes.

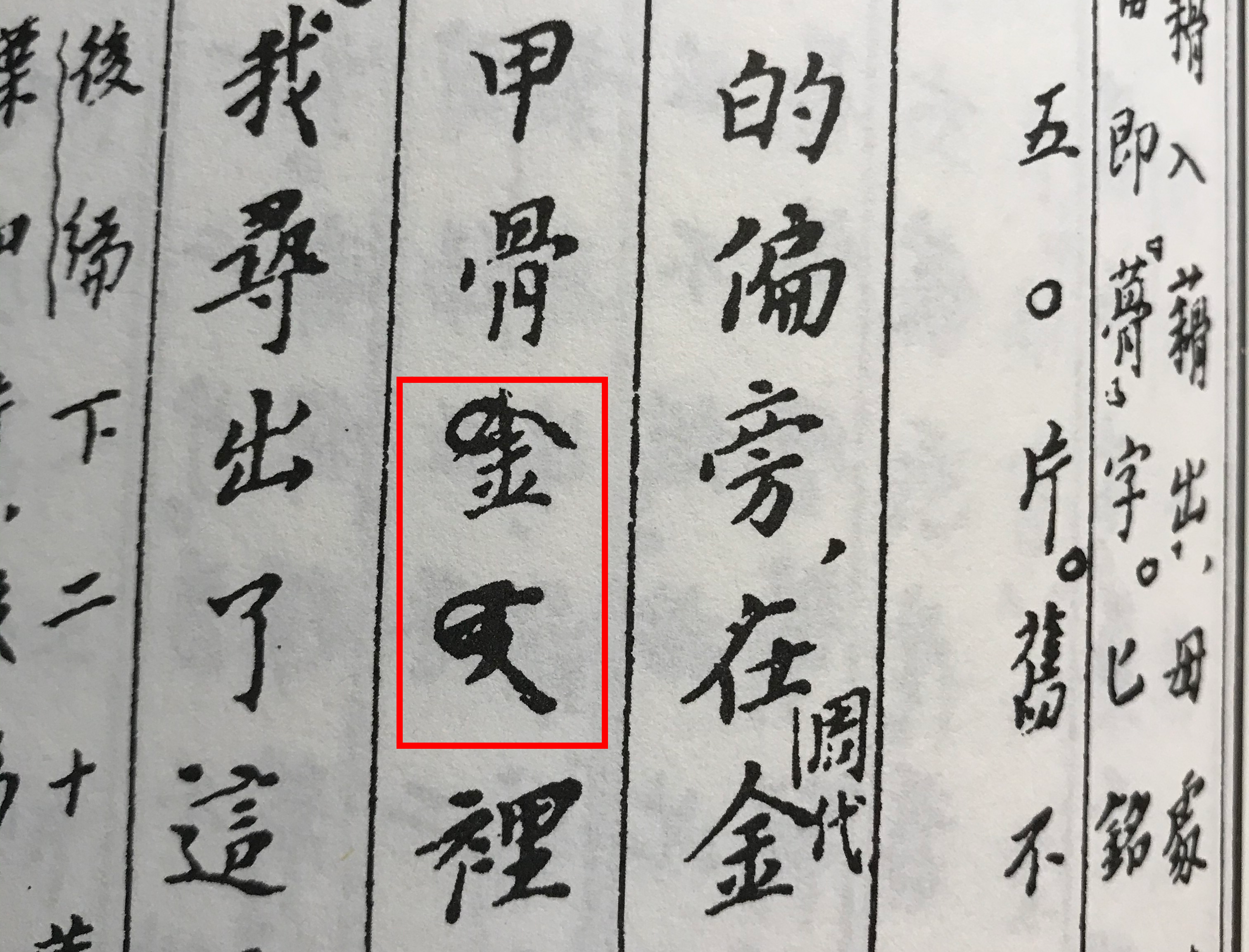

Stroke names

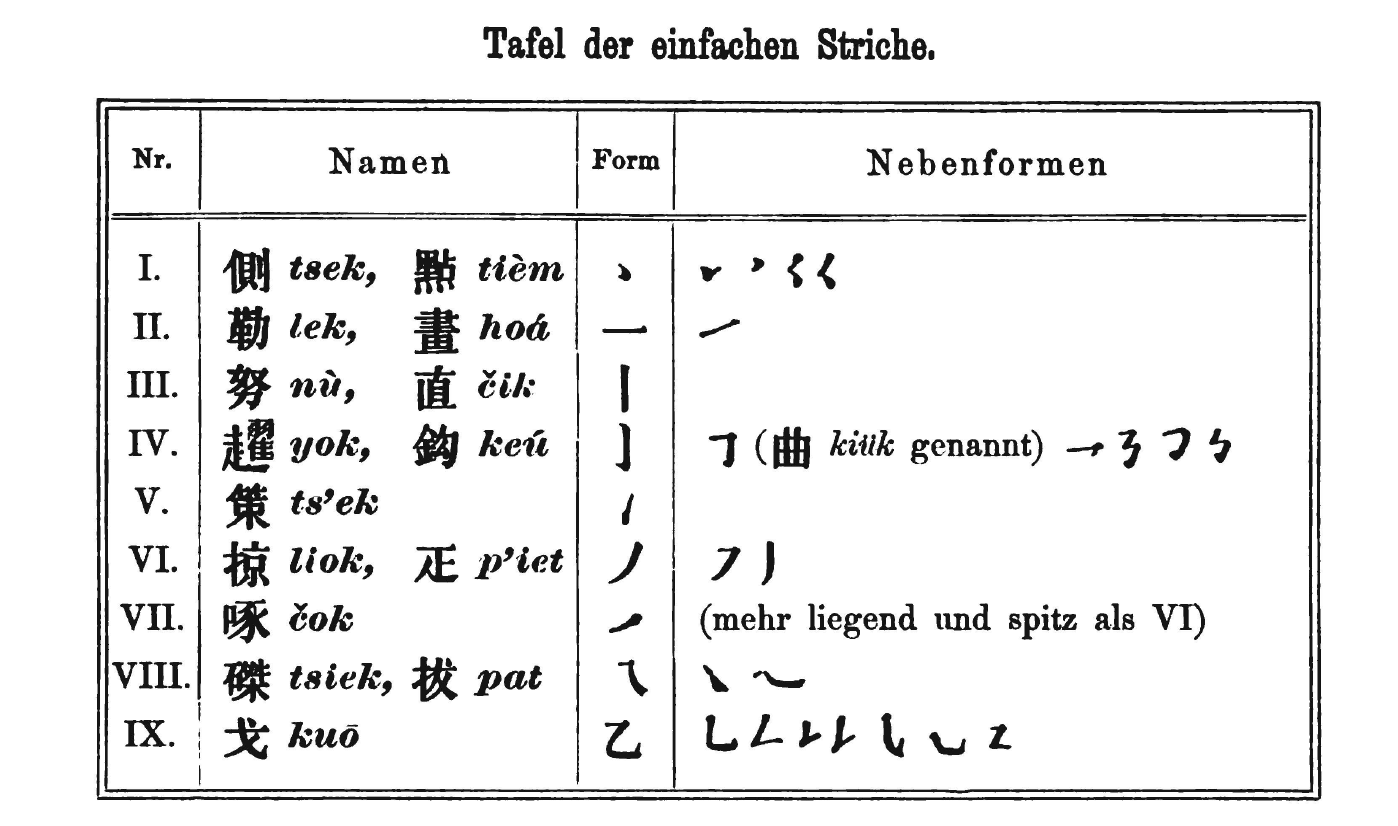

And in the section on the lexicographic ordering of characters, von der Gabelentz also gives the huge table with the 214 radicals from Kangxi Dictionary, but apart from that he also gives a smaller table of the basic strokes, together with their names and variant forms. Some of the names sound a bit alien to me but maybe that’s because I only know the modern colloquial names of these strokes. 😅

Punctuation

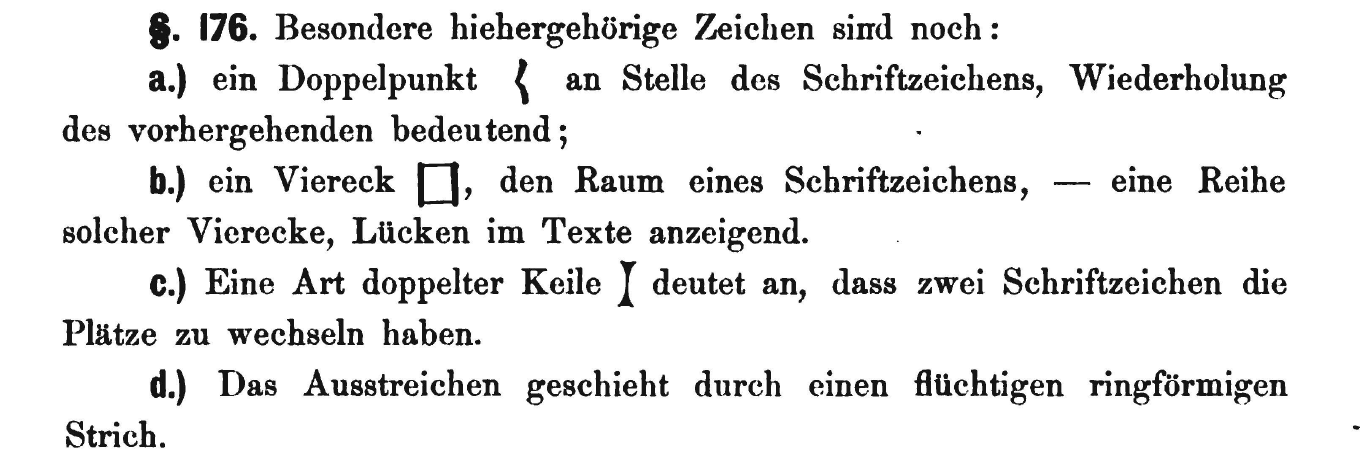

Even the punctuation bit in von der Gabelentz’s book contains more details than that in the other books. For instance, it not only introduces the usual Classical Chinese punctuation marks but also lists a few commonly used special symbols, including two placeholder symbols and two text adjustment symbols.

Von der Gabelentz doesn’t draw the character-deleting circle for us, so I’ve found an example from an alternative source.

Missing info

The only piece of information that I’ve found in Marshman’s book but haven’t in von der Gabelentz’s is that on recursive character formation, though I’ve notice something vaguely relevant:

Besteht von den beiden Theilen der eine aus einem Radicale, der andere aus einer Zusammensetzung mehrerer Radicale, so gehört in der Regel das Schriftzeichen unter jenen ersteren Radical. Also 慾 yuk, lüstern, 61 + (150 + 75), unter 61, 智 čí, Weisheit, unter 72. Ausnahme z. B. 楚 ts'ù, Dickicht, unter 75, nicht unter 103. (Chinesische, p.75)

“If one of the two parts [of a compound character] consists of a single radical and the other consists of a combination of multiple radicals, then the character normally falls under the former radical. So 慾 yuk ‘lustful’ 61 + (150 + 75) falls under Radical 61, and 智 čí ‘wisdom’ falls under Radical 72. Exceptions [to this general rule include,] for example, 楚 ts'ù ‘thicket’, [which falls] under Radical 75 instead of Radical 103.”

I’ve also noticed a wrong character transcription in the section on character history 😂, where the ancient script name 籕 zhou4 (in pinyin) or čeú (in the author’s romanization system) is wrongly transcribed as lieú. Besides, the proper character should actually be 籀, while 籕 is merely a vulgar allograph of it that had arisen from historical miscopying (à la Hanyu Da Cidian).

Taking into account all the merits of the character part of von der Gabelentz’s book as well as its tiny imperfections, I give it four and a half stars out of five.

Leave a comment