Some time ago I came across a short video on YouTube featuring the TV celebrity Jason Silva, who passionately talked about the underlying dynamicity of the universe. A particular metaphor he used caught my attention, which likened physical reality to linguistic parts of speech—

Matter acts, but there are no actors behind the actions. The verbs are verbing all by themselves without a need to introduce nouns.

The source of the slogan

Jason Silva attributed the quote to the physicist David Mermin in the video, though unfortunately I wasn’t able to trace it back to its original source. According to this blog post it was from an American Journal of Physics article “What is quantum mechanics trying to tell us.” However, after searching through that article (both the published version and the arXiv version) I didn’t manage to find any mention of “noun” or “verb.” The article does cite Wittgenstein, though, which suggests that the author did think about language and its philosophy in his process of writing:

We cannot think of any object apart from the possibility of its connection with other things. (Wittgenstein, Tractatus)

The author’s own remark about quantum mechanics also has a Wittgensteinian air:

Correlations have physical reality; that which they correlate does not.

I gather this might actually have been the basis of “verbs are verbing,” and of course whoever came up with that slogan was no doubt a genius! To my best knowledge it might have been the astrophysicist Piet Hut, who wrote the following words in his entry in the online column “2000: What is today’s most important unreported story?” hosted by edge.org:

Two voices have recently stressed this verb-like character of reality, those of David Finkelstein, in his book Quantum Relativity, and of David Mermin, in his article “What is quantum mechanics trying to tell us” [1998, Amer. J. of Phys. 66, 753]. In the words of the second David: “Correlations have physical reality; that which they correlate does not.” In other words, matter acts, but there are no actors behind the actions; the verbs are verbing all by themselves without a need to introduce nouns. Actions act upon other actions. The ontology of the world thus becomes remarkably simple, with no duality between the existence of a thing and its properties: properties are all there is. Indeed: there are no things.

This looks like a verbatim source of what Jason Silva quoted in his video. From a linguistic viewpoint, the slogan sounds smart because it involves an ad hoc conversion of the noun verb into a verb to verb (that’s quite a mouthful!). And since to verb is not an existing word in the dictionary, its exact meaning is completely up to the definition of whoever invented it.

Referentiality

The noun verb and the verb to verb—that almost sounds like a wordplay or a tongue twister! The trick here is mixed referentiality. In linguistics there’s a fundamental distinction between the use and the mention of an expression. Take for example the two sentences below, which are from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Jim went to Paris.

- “Jim” has three letters.

The first Jim refers to a person (that’s the use of the word Jim), while the second “Jim” refers to the three-letter word itself (that’s the mention of the word Jim). You might have thought that was easy, because the mention-type referentiality is indicated by quotation marks. But bear in mind that all typographic hints vanish in oral speech, which certainly adds to the possibility of confusion.

An even more confusing phenomenon concerning referentiality is the accidental or deliberate employment of self-reference; namely, reference to (part of) a statement within the statement itself. Those of you who’re programming-minded might be thinking that sounds like recursion, and you’re right—according to Wikipedia recursive definitions in programming languages do involve self-reference, though they do so in a much less confusing fashion. Compare the following examples for an illustration:

- $ f(0) = 1, f(n+1) = 2 * f(n) + 1 $

- This sentence is false.

The first example defines a function $ f $ by referring to $ f $ itself. However, as a mathematical function $ f $ simply maps input to output, and we don’t have to ever think about its truthfulness or deceitfulness. The same is not true for the second example, which as a syntactically well-formed English sentence in principle makes a proposition with a truth value. The trouble is we don’t really know whether the sentence is true or false 🤯. It’s a “Schrödinger’s sentence” in a sense—a paradox for us mundane creatures…

Nonlinguistic uses of part-of-speech terms

I’ve long noticed that sometimes linguistic terms get creative uses in nonlinguistic contexts, and that’s especially true for part-of-speech terms, perhaps because they are the best-known kind of linguistic terms outside linguistics. Apart from “verbs are verbing,” Jason Silva also mentioned “God is a verb” in his video, which is the title of a book. I haven’t read the book (nor does it look like the type of book I normally dig), but with that title I’m sure it’d catch many window shoppers’ attention.

And of course, as a native Chinese speaker I’ve also heard similar nonscholarly uses of part-of-speech terms in Chinese. For example, the Mandarin term for “noun”—míngcí 名詞—is often used by nonlinguists as a synonym of “terminology” or “uncommon/new name.” For example, upon hearing something (be it a noun or not) they’ve never heard before, someone might say (often in order not to lose face):

- nà búguò shì yígè xīn míngcí bà le

那不過是一個新名詞罷了。

“That’s nothing but a new term (i.e., it’s no big deal and don’t try to fool me).”

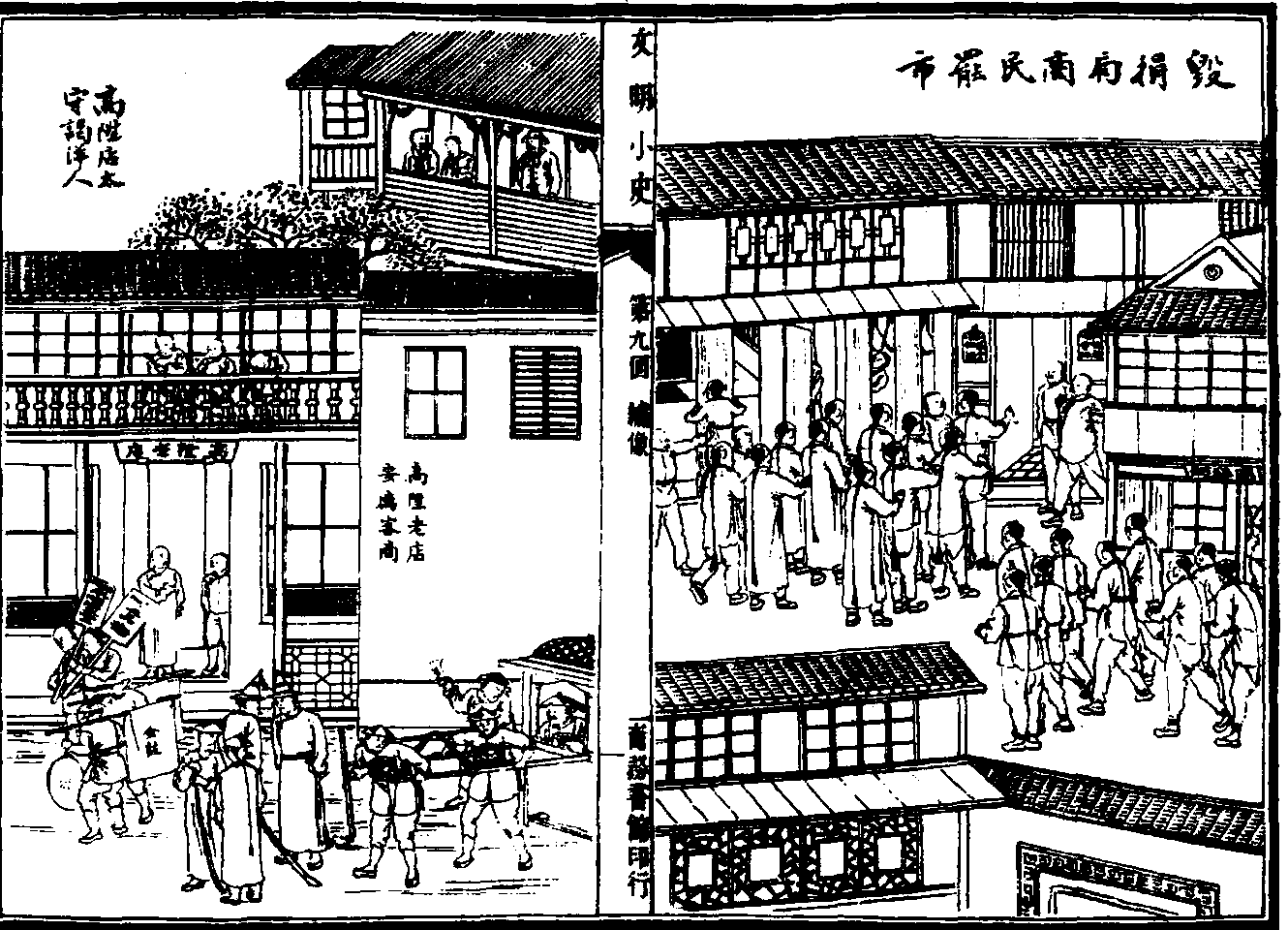

Strikingly, this nontechnical use of “noun” is nothing new but has been there in the Chinese language for at least a century, and the phrase xīn míngcí 新名詞 has even made its way into dictionaries, presumably as an idiom. The following example is from the 1906 novel Short History of Civilization (文明小史) via the Revised Mandarin Dictionary of the ROC Ministry of Education:

- cǐ fān tīng-jiàn xiānsheng shuō-le zhè zhǒng xīn míngcí, dào yào qǐngjiào-qǐngjiào

此番聽見先生說了這種新名詞,倒要請教請教。

“Now that I’m hearing this new term from you, I’d like to ask you for an explanation of it.”

Similarly, the Chinese term for “adjective”—xíngróngcí 形容詞—also has a nonscholarly use. It has come to mean any word or expression whose function is to help explain something else rather than claim its own, literal truth. TV celebrities often use this word to “disculpate” themselves of accidental remarks that might be perceived as offensive or inappropriate.

For example, the Taiwanese politician Wang Shih-chien likes making public bets on election results, and during the 2018 election season he said he’d jump into the sea should Han Kuo-yu be elected as Mayor of Kaohsiung. Then, after Han did win the mayor election, he jokingly invited Wang to jump into the Love River at Kaohsiung, and the latter had to clarify on TV that jumping into the sea was just an “adjective”:

- tiào-hǎi zhǐ shì gè xíngróngcí!

跳海衹是個形容詞!

“Jumping into the sea is just a describing-expression (i.e., I didn’t really mean it)!”

How semanticists view nouns and verbs

As a final remark on the “verbs are verbing” slogan, perhaps no professional linguists would seriously agree to the idea that verbs can “verb” all by themselves without a need to introduce nouns, because linguistically speaking the very purpose of word classes is to acknowledge their contrasts, and—in a slightly philosophical tone—just as there’s no black without white and no day without night, there’s also no verb without noun. Verbs in any language can be recognized as verbs precisely because they have in a unique, “verby” way not seen on other parts of speech.

Nevertheless, that doesn’t affect the expressiveness of the aforementioned metaphor, because the physicist who invented the slogan was clearly using “verbs” to mean dynamic, continuous correlations and using “nouns” to mean static, individuated objects. That’s absolutely fine because verbs do convey various correlations between nouns in human language. For example, in John bought a T-shirt the verb bought correlates the two nouns John and T-shirt.

Thus, the parallelism the metaphor draws upon is not about the grammatical or syntactic features of verbs and nouns but rather about their semantic features. And in model-theoretic semanticists’ eyes the statement “there are no things but only properties” actually doesn’t sound that crazy, because in semantic terms verbs and nouns do both denote predicates, whereby nouns always have an underlying verby nature. For example, the noun T-shirt is the predicate that picks out all those items that are T-shirts from some universe of discourse; in other words, it denotes the property of being a T-shirt.

Physics vs. cognitive science

So, according to quantum physicists, the reality we are embedded in is entirely made up of “verbs”—or dynamic processes—while the “noun”-“verb” distinction of the world is just an illusion. That leads to another interesting question: Why do human beings have this illusory perception? Is it a result of the physical properties of the universe itself or rather a proclivity of the human mind? If it’s the latter, then perhaps the mind-body dualism is real after all, for there are questions about the world that physicists don’t have an answer to but cognitive scientists might do.🖖

Leave a comment