This is the second part of my “portfolio” prepared for the virtual poster session at ACT2020. It introduces my category-theoretic modeling of the human language grammatical type (aka syntactic category) system. The technical detail can be found in my dissertation “On the formal flexibility of syntactic categories.” This article is a conceptual synopsis, with some occasional remarks not included in my dissertation.

(Quick advertisement: I also have a Category Theory Notes series on this blog, which is a compiled collection of my personal study notes as a non-math-major beginner and records some of the confusions I had had in the process of learning as well as how I overcame them in the end.)

Overview of my ACT2020 portfolio:

- Part I: Category Theory and Generative Grammar (a 9-min explainer video laying out the disciplinary background in plain words)

- Part II: A new application of category theory in linguistics (a blog article summarizing my application of category theory in linguistics)

- Part III: Grammatical types that cannot be: A category-theoretic theorem for Chomsky-school generative syntax (a revised version of my extended abstract submitted to ACT2020, which showcases a specific result out of the application in Part II)

- Part IV: the actual virtual poster

Since this is the first step in a potentially long-term project, feedback from both linguists and mathematicians (or applied category theorists from other fields) is highly appreciated. If you are attending ACT2020, feel free to drop in the virtual poster session (July 8, 20:00 – 22:00 UTC) and find me in this jitsi room for a discussion.

A note on terminology: What I call “grammatical type” here is more widely called “syntactic category” in linguistics. I am adopting the unusual term because “category” already has a different default meaning in the context of ACT2020.

Category theory and linguistics

Category theory has already been applied to linguistics, but its application so far has been limited to two subfields: categorial grammar and natural language processing. While I admire the rapid progress in those subfields (see, e.g., this paper and this StackExchange discussion for an impression of the general direction being taken) and am trying to learn the latest theoretical tools myself, I believe that the potential applicability of category theory in linguistics goes beyond them. My research demonstrates that category theory can also be a valuable source of inspiration for the less computationally driven subfields of linguistics, in particular for the ontological foundations of Chomskyan generative syntax.

Natural language grammar encompasses two basic modules: a rule-based computational module (i.e., the syntax) and a storehouse of the units the rules operate on (i.e., the lexicon). Previous linguistic applications of category theory mainly deal with syntactic computation; in my application I mainly pay attention to the (syntactically relevant part of the) lexicon.

Grammatical types

Type information is an indispensable part of the lexicon. Every natural language unit—be it a concrete word like cat or an abstract unit like the “little v” (a Chomskyan functional keyword responsible for licensing the doer/agent of the verbal action)—has a type (like a word class) specified in the lexicon, which is then referenced by the (narrow) syntax.

Different linguistic theories make different assumptions about grammatical types. Some theories (e.g., categorial grammar, model-theoretic aka formal semantics) assume a very parsimonious type ontology—which partially has to do with the philosophical notion ontological commitment (see also this paper in relation to natural language semantics)—while others (e.g., head-driven phrase structure grammar, transformational-generative grammar) are less concerned about the parsimony issue. An extreme case of ontological richness is the branch of transformational-generative grammar known as “cartography” (and especially its “nanosyntax” offshoot), where dozens or even hundreds of ground types are proposed.

It should be noted that type parsimony comes with a cost in theoretical linguistics. Chomsky famously proposed three levels of adequacy for linguistic theorization: (i) observational adequacy, (ii) descriptive adequacy, and (iii) explanatory adequacy. Natural languages as we know them are not really parsimonious with grammatical types, at least on the observational and descriptive levels. Thus, while a type inventory exclusively built on $e$ (for entities) and $t$ (for truth values) can no doubt derive all kinds of sentences at the logical level, it is hardly conceivable how it can adequately encode grammatical concepts like evidentiality, ergativity, and honorific—which are crosslinguistically attested and widely documented—without a significant amount of counterintuitive tweaking.

As such, some fundamental distinction must be made between grammatical types and logical types. While logical types only need to make an algebraic-derivational system formally converge, grammatical types also need to cover the empirical-descriptive reality of human language—that it is anything but handcuffed in grammatical typing! Consider the noun classification systems in Bantu languages for a vivid example:

While no single [Bantu] language is known to express all of them, most of them have at least 10 noun classes. For example, by Meinhof’s numbering, Shona has 20 classes, Swahili has 15, Sotho has 18 and Ganda has 17. (Wikipedia)

Once we accept the empirical fact that human language is not so poor in grammatical type ontology, a subsequent question is: Is the grammatical type inventory of human language structured?

I take it for granted that no linguists seriously think that the mental lexicon of human beings is a chaotic bag of words—there are at least the subsumption (aka is-a) hierarchies based on superordinate/subordinate classification (e.g., a cat is an animal, a plural noun is a noun). However, the structure of grammatical types must go beyond classificatory hierarchies. Specifically, grammatical types are types referenced by syntactic rules, so their ontological structure must be at least partly grammatically/syntactically based but cannot be simply or entirely based on an is-a relation.

As far as Chomskyan syntax is concerned, there are independently proposed ideas in the literature about various aspects of the grammatical type ontology—most noticeably by acknowledging the existence of “extended projections” (see below)—but dedicated, thorough explorations of the inventory are still few and far between. The aim of my research is to show that category theory can help linguists in this respect. Namely, it provides a suitable tool to help us flesh out the formal structure of the human language grammatical type inventory.

Extended projection

Definition

The Chomskyan syntactic notion extended projection plays a central role in my category-theoretic modeling of the grammatical type inventory.

NB “extended projection” should not be confused with the historically related notion “extended projection principle” (see this book chapter for a more technical linguistic discussion).

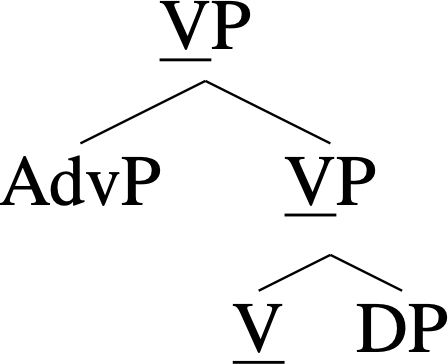

A projection is an endocentric structure built upon (or metaphorically “projected from”) a core type (called a “head”). For example, the following tree diagram represents a projection of V (short for “verb,” and P stands for “phrase”). Notice how the underlined type V “percolates upward” from the most deeply embedded level. (An example sentence with this structure is quickly eat the cookies.)

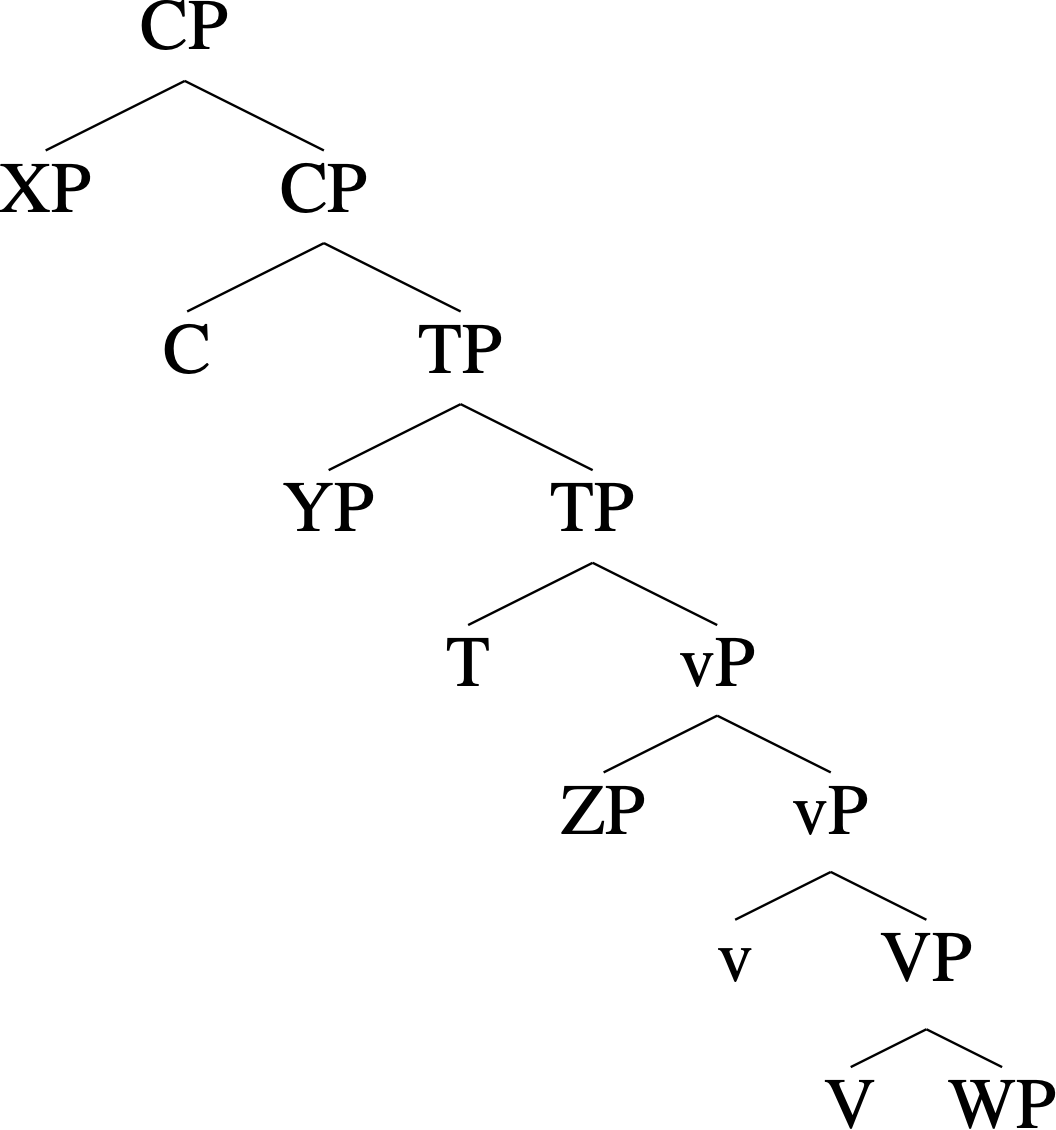

Trees like this can grow very large, especially in the aforementioned “extremal” branches of generative grammar. But a moderate-sized tree in a syntactician’s everyday work looks like the following (X, Y, Z, and W are placeholders for types irrelevant to the “projection spine”):

An example sentence with this structure is What did John eat? Here VP (e.g., eat cookies) is the lexical or core semantic projection, while all the other projections above VP—including vP for agent-licensing (e.g., John), TP for tenses (e.g., past tense), and CP for complementizers and clause typing (e.g., interrogation)—are considered extensions of it, hence the term “extended projection.”

Importantly, in the context of an extended projection, which type projects first and which projects next is not random but follows some semirigid ordering. There are debates as to what the exact ordering is, but here I merely emphasize the point that there exists some kind of order relation among grammatical types, which is sufficient for my category-theoretic modeling.

Connections between extended projections

Extended projections are a qualified structural unit for the grammatical type inventory. Furthermore, linguists have proposed various higher-order ideas building on them. For example:

- Extended projections group grammatical types that belong to the same major part of speech together, so linguists often abstract away from their internal detail and simply refer to them as “the verbal extended projection,” “the nominal extended projection,” and the like.

- The grammatical types in an extended projection fall in subsets (alternatively known as domains or zones) based on their syntacticosemantic functions. For example, the above-mentioned V and v are both “v-domain” or “vP-domain” types.

- There are certain conceptual parallelisms between extended projections from different major parts of speech. For example, T (for tense) is to verbs what D (for determiner) is to nouns. And certain conceptual templates have been proposed to represent such parallelisms, such as the “universal spine” in Wiltschko’s 2014 monograph The Universal Structure of Categories.

- There are certain inheritance relations (often metaphorically referred to as “split-X” or “split-XP”) between extended projections of different sizes from the same major part of speech. For example, the above-mentioned V-v-T-C projection sequence can be expanded to the more detailed sequence V-Appl-v-Voice-Asp-T-C-Foc-Top, where Appl/v/Voice are “split-v” types and Foc/Top are “split-C” types.

(If you are interested in the additional types in my last example, they are applicative, voice, aspect, focus, and topic.)

If there is a syntactically based ontological structure for the grammatical type inventory, the above higher-order ideas should also be part of it.

For the remaining content of this article see my next post “A new application of category theory in linguistics (part 2)”.

Leave a comment