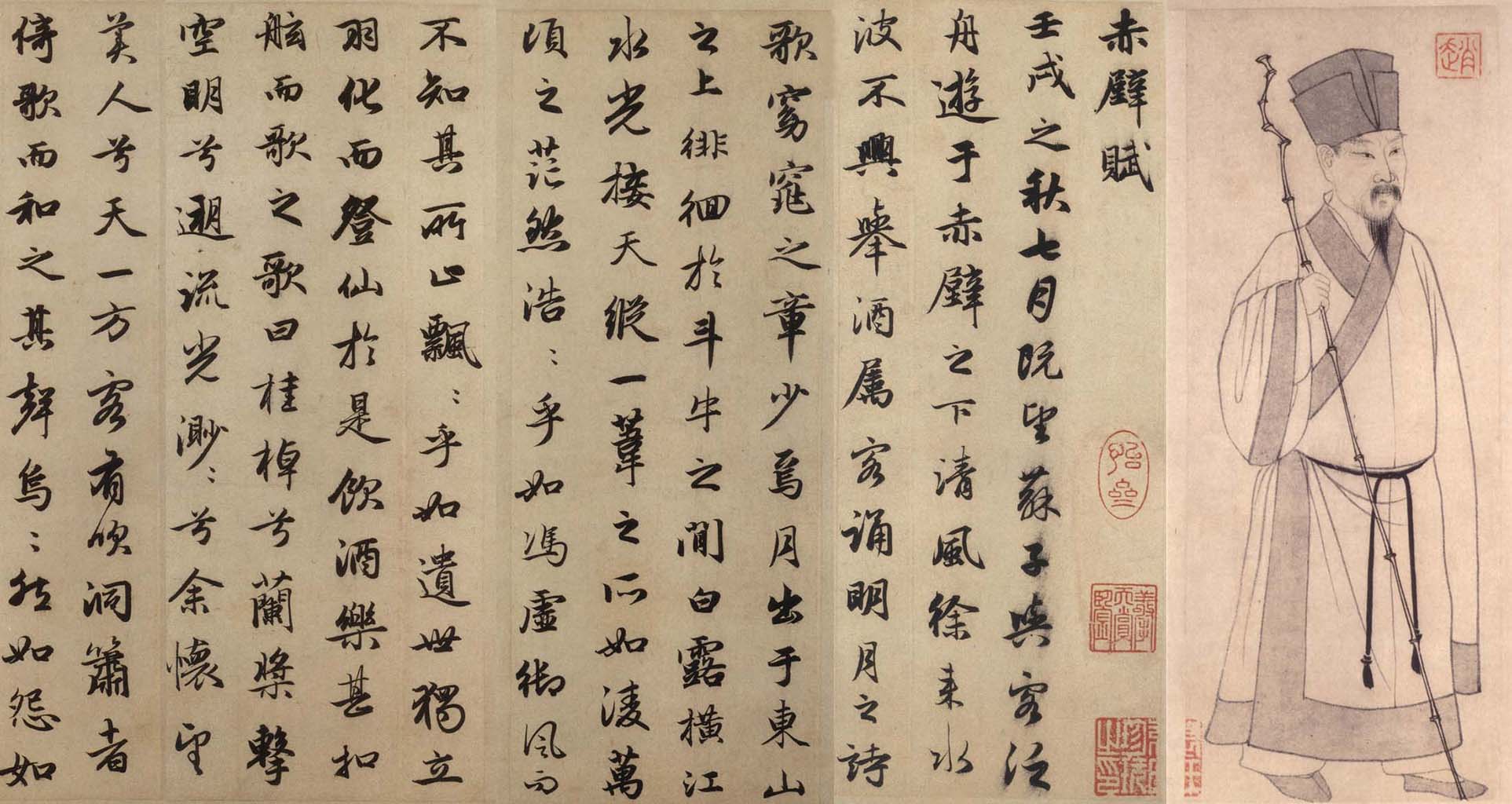

Recently I randomly came across a passage about language in a historical Chinese document. It’s in a short essay written by the famous writer and poet SU Shi (蘇軾)—though not the passage in the picture below—who lived in the Northern Song Dynasty (born in 1037 CE and died in 1101 CE) and was one of the Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song Dynasties (唐宋八大家).

SU Shi’s achievements in literature and arts are so remarkable that his essays and poems are an obligatory part of school education in China. By the way, SU Shi was also a gastronome. Allegedly he was the inventor of the popular dish Dongpo Pork (東坡肉; Dongpo is SU Shi’s other name), which is now sold in Chinese restaurants around the world.

“Odd Stone Offering”

The short essay that I came across is entitled Guài Shí Gòng (怪石供), which literally means “Odd Stone Offering”—so named because SU Shi collected some oddly shaped pebble stones and used them as a Buddhist offering. The essay is also known as Qián Guài Shí Gòng (前怪石供) ‘Former Odd Stone Offering’ because SU Shi also wrote a follow-up essay—sort of like a sequel—where he recounted what had happened after he had offered the odd stones to Buddha (well, basically nothing happened…). This sequel essay is known as Hòu Guài Shí Gòng (後怪石供) ‘Latter Odd Stone Offering’.

The main story in Former Odd Stone Offering is rather dull in my opinion, and I wouldn’t have remembered it at all if it had not been for the language-related comment. The essay mentions an exotic country as an analogy to illustrate how odd the stones are. In that country people can’t speak and communicate via a “sign language” (of course SU Shi didn’t use this modern term) instead.

There’s an overseas country using visual language. People there can’t speak with their mouths but communicate visually instead. Communication in this visual language is faster than communication by mouth.

(海外有形語之國,口不能言,而相喻以形。其以形語也,捷於口。)

The essay continues to remark that even though the visual language looks very convenient and efficient, if the author were made to use it, he’d find it utterly difficult to get used to. And there comes the moral: The notion of oddness is only relative. If most stones in the world looked like what the author had collected, then it’d be the stones we now see everyday that should be called “odd.”

The essay doesn’t specify where exactly the “country of visual language” is located, but since China is only half-surrounded by sea, I guess it might be some island in the Pacific Ocean. But is there really such a country? And how had SU Shi learned of it? I don’t know. I just find it surprising that sign language was already considered a proper type of language with equal status to spoken language (at least in terms of “oddness”) by Chinese literati a thousand years ago, especially considering how many people (scientists included) nowadays still think sign language is just a “performed” version of spoken language!

“Ghost script”

My random discovery of SU Shi’s essay—which as far as I’m concerned isn’t among the most well-known works of his—reminded me that there might be more interesting stories about language in historical Chinese documents and folklore. They might not have much scientific value but are nevertheless a direct window into ancient ideas about language.

So I started scanning my memory and, before long, suddenly remembered another language-related story—that about the so-called ghost script (鬼書), also known as the script of the extinguished (i.e., the dead) (殄文). It perhaps didn’t make its way into works of officially recognized scholars (because it’s too folkloric) but definitely appears a lot in contemporary fiction, especially in adventure novels about tomb raiding or Taoist battles/contacts with nonhuman beings.1 These novels are very popular among young people, and some of them have even been adapted into movies or TV series (such as Guǐ Chuī Dēng [鬼吹燈] ‘Ghost Blows Out the Light’).

The ghost script is, as its name suggests, a kind of script used by ghosts. Ordinary human beings can’t understand it, though it can be learned (yes the Taoist world is very fair!), and those who have mastered it can work as “translators.” 🗣 Since I first learned of the ghost script in fiction, I simply assumed that it was something made up by novel writers. But as it’s mentioned so many times and portrayed so mystically, I decided to give it a search. To my surprise, it turned out to be a real script in actual use!

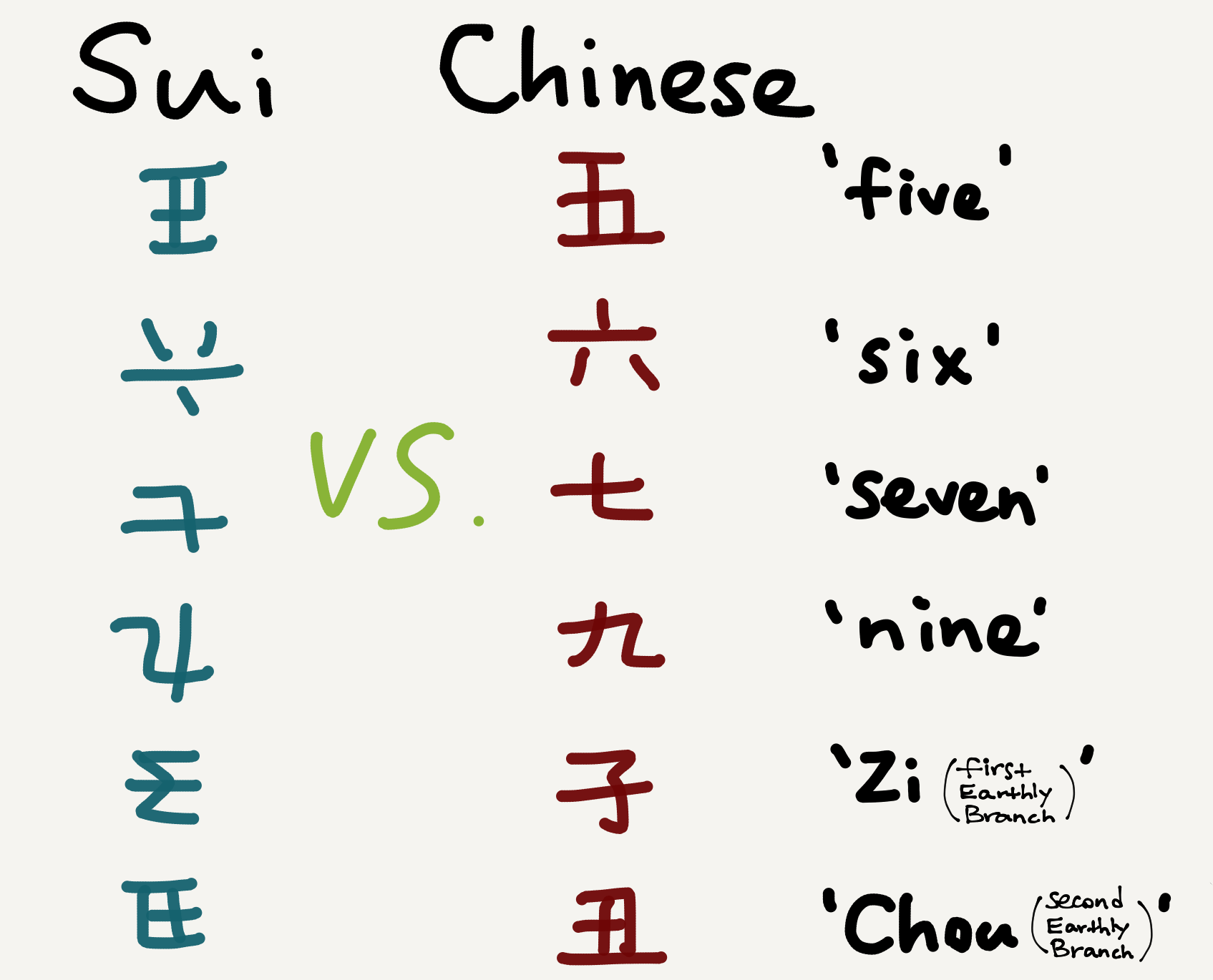

Well, the ghost part is just an exaggeration, but the script itself indeed exists. Its official name is “Sui script” (水書) because it’s the script used by the Sui ethnic group (水族) living in Southwestern China (Guizhou Province).2 Traditionally the script is only mastered by local shamans for ritualistic (e.g., divination) purposes, but the Chinese government is now trying to protect it—as well as the Sui language it records—from extinction. But again, it’s probably exactly due to its ritualistic nature that the Sui script has been correlated with ghosts. According to Wikipedia:

Many of [the Sui] characters appear to be borrowings from Chinese characters and are written backwards, apparently for increased supernatural power.

As a nonstandardized script, Sui has multiple variants for almost every character. I’ve picked some Sui characters below that are most obviously backwardly written Chinese characters.

According to fiction writers (and whoever they heard it from) the backwardness of the Sui script is for the convenience of ghosts, who see things from “the opposite side.” So things that look backward to us are actually forward to them! But doesn’t that make the Sui script just a particular variant of the Chinese script?😵By comparison, the folkloric explanations are much less spooky. I’ve seen the following two versions, both of which have to do with the inventor of the script, a figure named LU Duogong (陸鐸公):

- First version: When LU invented the Sui script, which wasn’t backward-looking in the beginning, an evil God was so jealous that he burned LU’s right hand as well as the script book. So LU could only rewrite the book with his left hand, in which process many characters got backwardly written.

- Second version: LU didn’t invent the Sui script by himself but learned it from a kind God together with five other old men. However, all his classmates died of illness on their way back home, which made LU the only one who could pass the knowledge on to his people. Unfortunately, all but one script book that he brought home got stolen, and LU had to rewrite the stolen books from memory. He deliberately used his left hand and wrote some characters backwardly for fear that the books might be stolen again and used for evil purposes.

I’m not sure which version is more credible, but at least one thing is certain: the “backwardness” of Sui characters in relation to Chinese characters is not our hallucination but a well-observed fact—and that in itself is a very interesting trait if we compare Sui with other scripts in the world, especially considering the Sui language and the Chinese languages don’t belong to the same language family!3 I think I might write on this interesting script again in some future post.

Language worship

There seems to be some sort of “language worship” in Chinese folklore. Apart from the above-mentioned ghost script, I can remember two more examples:

- As Huainanzi ‘Writings of the Huainan Masters’ (a collection of scholarly debates that took place sometime before 139 BCE) mentions, when Chinese characters were invented, “it rained grains from the sky and ghosts all cried at night” (天雨粟,鬼夜哭)—because from that moment on men could accumulate and pass on knowledge and nature could no longer keep secrets.

- In the Taoist worldview animals, plants, and even inanimate objects can all acquire God-like powers via special exercises (which usually take hundreds of years), and a most important criterion to gauge the success of the “exercising” animals/plants is that they begin to understand human language. So, in a sense language has long been treated as a hallmark of intelligence in Taoism, long before the advent of modern linguistics.

I like reading such language-related snippets in historical documents as well as fiction and folklore, partly because I’m a linguistics student and partly because I always find it amazing that people can have metaphysical reflections on the human language capacity whichever era they live in. I’ll keep collecting similar stories and you’re welcome to share language-related stories with me as well.😃

2.↩ The “Sui” here (aka “Shui”), though written as 水 in Chinese, has nothing to do with the literal meaning of that character (i.e., water). The character is merely used to represent the sound instead.

3.↩ Sui belongs to the Kra-Dai family while Chinese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan family.

Leave a comment