In my previous post Carving civilization into stone…and the “Chinese Rosetta Stone” (Part 2) I introduced an inscribed stone tablet in Chinese history, called the Three-Type Stone, that to some extent resembles the Egyptian Rosetta Stone. I also started comparing the two stones, focusing on their similarities. In this post I’ll continue writing about their differences. 😃

Rosetta Stone vs. Three-Type Stone (continued)

If we look more carefully at the inscriptions on the two stones, we can quickly notice that they are actually quite different. I have summarized the following most noticeable differences for them.

Difference 1: interscript relation

First, the three scripts on the Three-Type Stone are different scripts for the same language variety (Old Chinese), so their symbols have a strictly one-to-one correspondence. By contrast, the three scripts on the Rosetta Stone are actually used to write three different language varieties: Ptolemaic Neo-Middle Egyptian, Demotic Egyptian, and Koine Greek. Many sources (Wikipedia included) treat the two Egyptian varieties as the same language, but strictly speaking they aren’t, as rightly pointed out on the Rosetta Stone Online project website accompanied by detailed linguistic illustrations. See below for a random sample from the website:

English translations:👆

a. Hieroglyphic: “In return for these things the gods and goddesses have given him victory, strength, life, prosperity, health and…“

b. Demotic: “As reward for these things the gods have granted him might, victory, strength, health, well-being and…“

c. Greek: “In return for which the gods have given him health, victory, power and…”

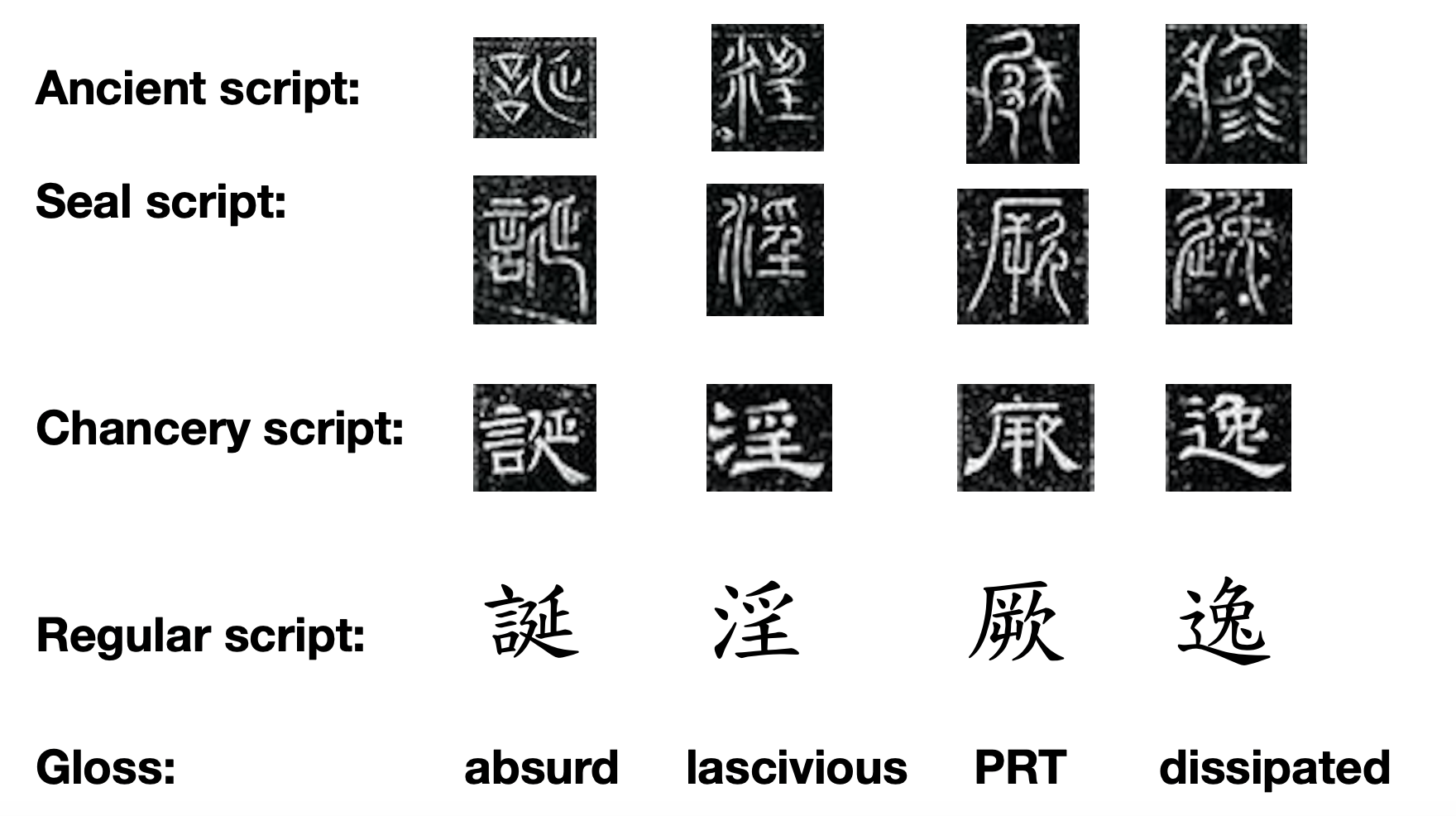

It can be clearly seen from the above sample, in terms of both choices of words and grammatical structures, that the relationship between three scripts on the Rosetta Stone is one of crosslinguistic translation. By contrast, the relationship between the three scripts on the Three-Type Stone is merely one of “font change,” so to speak, because they all record exactly the same text in exactly the same language. See below for a glossed sample (taken from the stone rubbing in Part 2):

English translation:👆

“(King Zhou is) absurd, lascivious, and dissipated…“

(The third character 厥 jue2 is a meaningless grammatical particle.)

Difference 2: creation time

A second clear difference between the Rosetta Stone and the Three-Type Stone lies in their creation times. The Rosetta Stone was carved during the Hellenistic period (in 196 B.C.E. according to Wikipedia), while the Three-Type Stone, as aforementioned, was carved during the Three Kingdoms period (in 241 C.E.). So, the Rosetta Stone was created much earlier than the Three-Type Stone. In fact, the creation time of the Rosetta Stone is closer to that of another famous seal-script inscription in Chinese history, the Imperial Edict of Qin (秦詔版 qin2 zhao4 ban3), which was created after the first emperor of Qin had unified China—that is, shortly after 221 B.C.E. A fragment of (the rubbing of) this inscription is in the background of this post’s title—scroll to the top for a look 👀, and here are more rubbings of it.

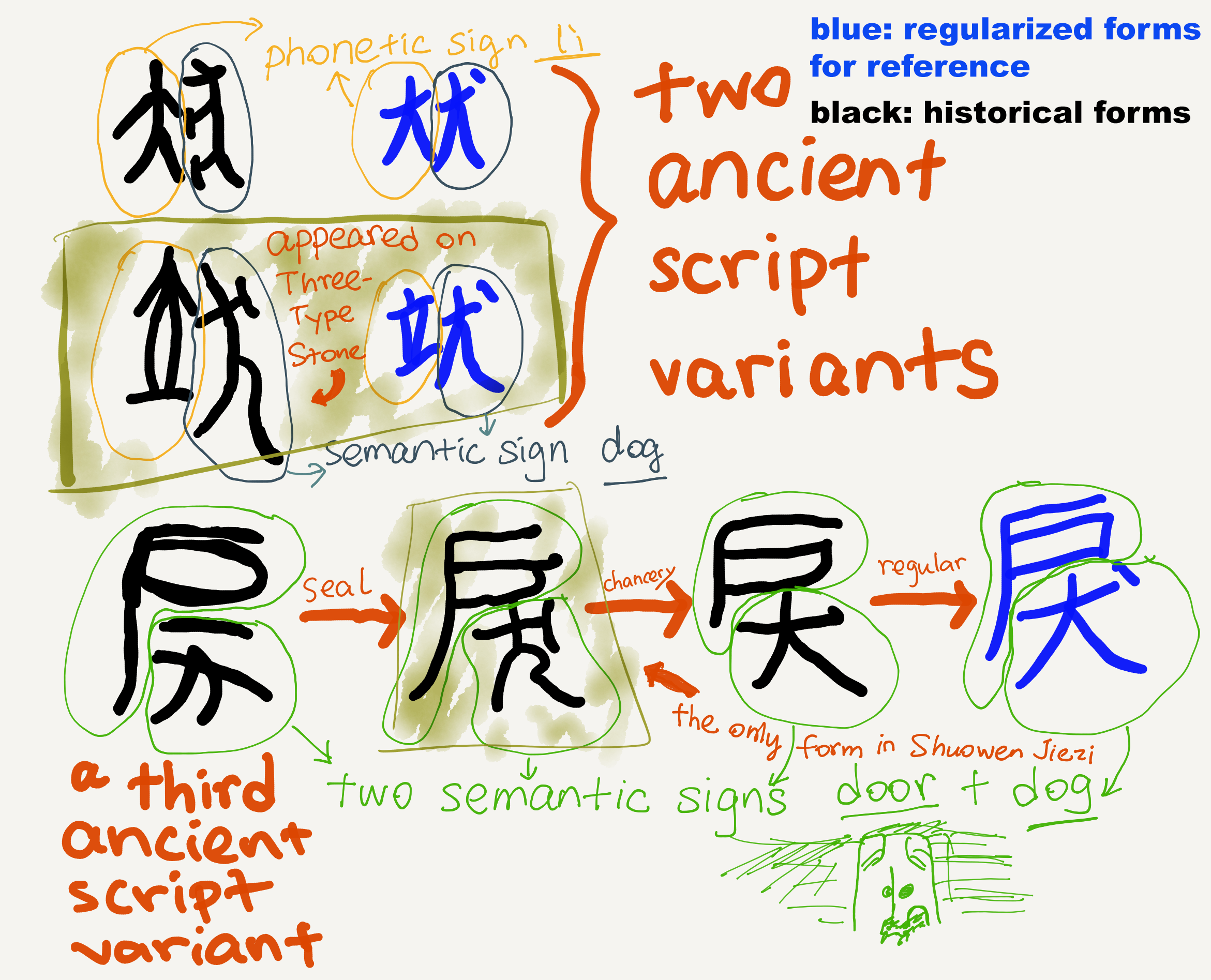

A direct implication of this discrepancy in creation time is that, unlike the Rosetta Stone, the Three-Type Stone couldn’t have played a crucial role in the decipherment of ancient Chinese scripts. Yes, it did provide more data to facilitate the process—such as in the decipherment of an ancient-script variant of the character 戾 li4 (see below, pardon my doodling)—but it couldn’t have been the indispensable bootstrapping material, for there are scholarly works and reference books on ancient scripts that predate it, among which the most famous one is none other than Shuowen Jiezi (compiled in 100 C.E.).

The Three-Type Stone wasn’t decisive in the decipherment of ancient Chinese characters because, on the one hand, scholarly studies of the Chinese writing system have never stopped in history, and available documentation can be traced back to Han Dynasty, when knowledge about the ancient scripts was still commonplace. In fact, in Shuowen Jiezi, the first comprehensive Chinese dictionary, the author systematically explained the structures of seal-script characters and also gave ancient-script versions where they were structured differently, though as the example of 戾 li4 shows, the author sometimes failed or forgot to include certain variants, and it is in situations like this that unearthed inscriptions like the Three-Type Stone become helpful.

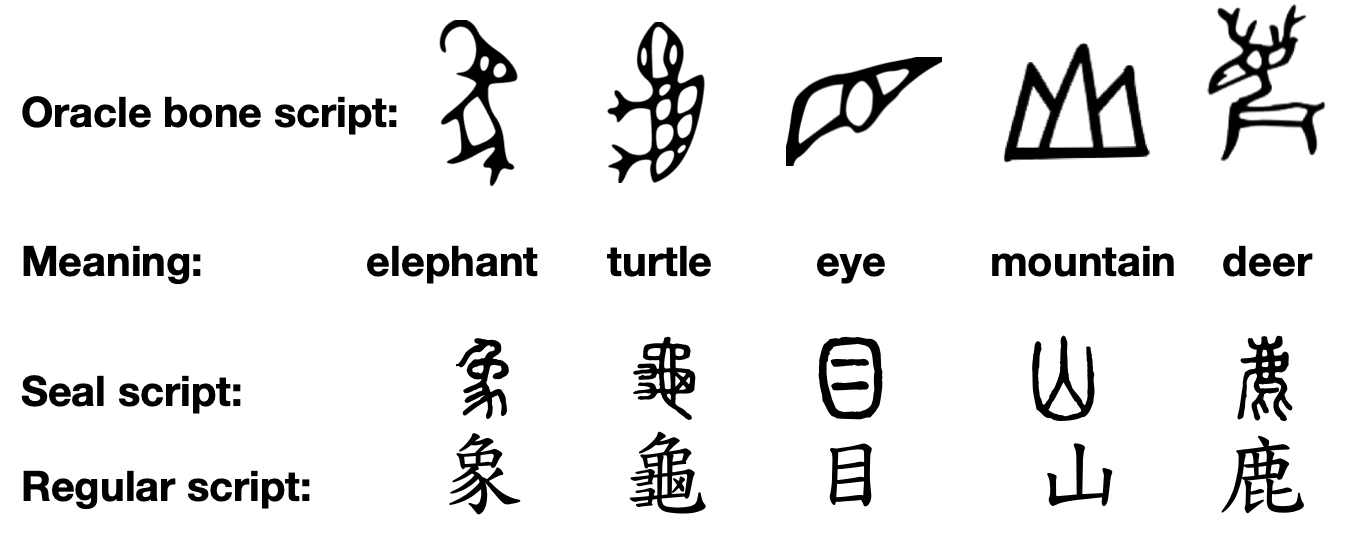

On the other hand, unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese characters as a whole have never fallen out of use, and later scripts have always inherited a bunch of characteristics and elements from earlier scripts. So, once we understand the basic structuring principles of Chinese characters (which are well documented and thoroughly explained anyway), we can quite easily recognize a number of ancient characters. Below are some examples:

In other words, in the case of ancient Chinese scripts, the decipherment task has never been about entire scripts (their basic designs, writing directions, etc.) but has been more about individual characters, much like inferring the meanings of difficult words during a B- or C-level foreign language exam, where it is taken for granted that examinees already possess fundamental knowledge about the language.

More on the role of language

Above I have mentioned the role of language in the decipherment of ancient Chinese scripts. In fact, on second thought, that role might have been an important one, because unlike the ancient Egyptian language, the variety of the Chinese language spoken at the time when the pre-Qin scripts were predominant didn’t really fall out of use, either, but became a purely written language (i.e., the so-called Classical Chinese) that would be painstakingly learned and nationally promoted in the next two millennia, all the way until early 20th century.

In sum, Chinese scholars actually possess three aspects of knowledge about the ancient characters that Egyptian scholars probably didn’t readily possess about the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs (that is, before the discovery of the Rosetta Stone):

- their basic building blocks (many of which are inherited by later Chinese scripts),

- their structuring principles (there are six overarching principles), and

- the grammar/lexicon of the language recorded by them (basically each character records a morpheme/syllable, and Old Chinese words are predominantly monomorphemic/monosyllabic, which in plain English means each oracle-bone character is a word).

The above three aspects of knowledge, plus China’s long history of documentation—which provided a cornucopia of comparative data (inscriptions, descriptions, closely related scripts, etc.) that greatly enhanced the efficiency and accuracy of the decipherers’ “guessing work”—made the decipherment of ancient Chinese characters a relatively easy-to-bootstrap task.

Also, for the truly difficult characters (many of which are proper names) that remain mysterious till today (despite the $15k reward!), the Three-Type Stone is pretty useless anyway, for it merely records a small subset of Chinese characters after all (the 2010 edition of Hanyu Da Zidian ‘Great Compendium of Chinese Characters’ includes 60,370 characters!).

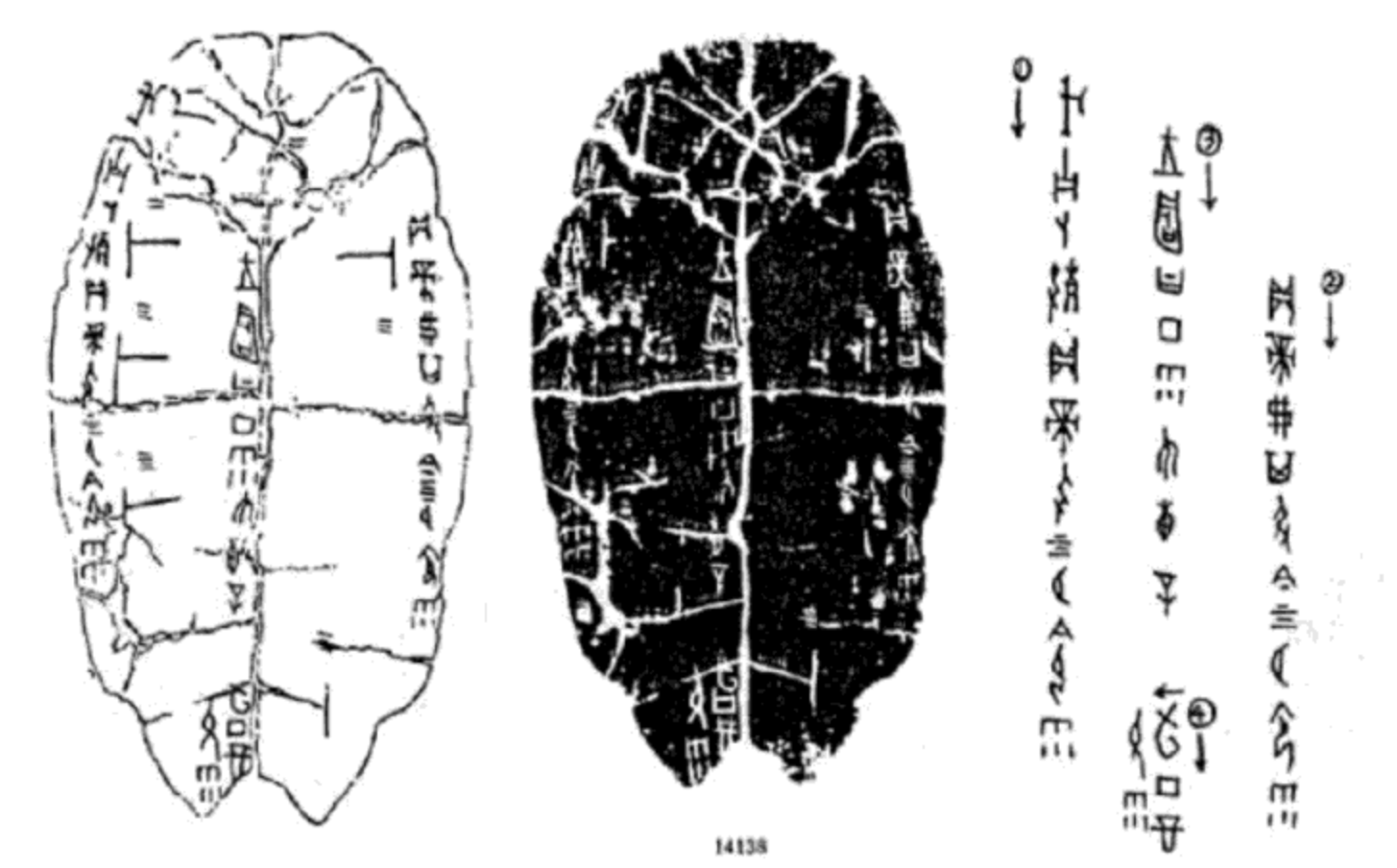

By the way, when one talks about the decipherment of ancient Chinese characters, one usually means that of the oracle bone or the bronzeware script, because later scripts (i.e., from the seal script onward) have never completely fallen out of use and so don’t need to be deciphered. The oracle bone script and the bronzeware script were actually used in the same period, only for different occasions—the bronzeware script was the more solemn and official script of the time, while the oracle bone script was a more casual and everyday script. But that makes the Three-Type Stone even less useful, for its three scripts don’t include the oracle bone script at all!

Final thoughts

So, based on the above reasons, I think the Three-Type Stone merely resembles the Rosetta Stone in form but not in essence. There may still be a Chinese Rosetta Stone buried somewhere, but that wouldn’t be the Three-Type Stone. In particular, if there were such a stone, it should be carved with at least both the oracle bone script and the “ancient” script, and it would be even more valuable if it also had the seal script on it.

However, that’s hardly possible in reality because if such an inscribed stone had been made at all, it could only have been made at a time when the seal script was predominant and the preseal scripts hadn’t been forgotten—namely, it could only have been created in Qin Dynasty. But unfortunately the first emperor of Qin was very bossy and relentless. He had burned most of the pre-Qin books two thousand years ago, which probably means that in order to promote his newly standardized seal script he had forbidden people to create any multiscript stones as well…🤦♂️

In any case, even without the help of a Rosetta Stone, we can still learn a lot about the ancient Chinese scripts, especially in an era where almost everything is digitized, though this in a sense brings us back to the initial story of this article (in Part 1). Digital devices are very powerful but also very delicate and require a lot of human-specific niche technology for data recovery, which makes them perhaps the worst medium to store our splendid but equally delicate civilization in the face of an almighty alien attack (like the dimensional strike in The Three-Body Problem).

On the other hand, stone-carving is slow, clumsy, and resource-demanding (we’d need the space and the stones!), but history has proved to us many times that it is also one of the most long-lasting methods if we really want to preserve something. So, maybe the next time you feel like composing something important and memorable, don’t post it on Facebook or Twitter—carve it in a piece of stone instead! In that way, even if no alien species will ever throw a two-vector foil at us, your note may still have the chance to become a valuable piece of inscription for future humans, just like the random (and often boring!) divination records on animal bones and turtle plastrons from two millennia ago, which are treated like gems today. 😂

==The End==

Leave a comment