In Part 1 of this post I wrote about an interesting Weibo hashtag I had seen, which was about some animal doodles on a 9th-century Chinese manuscript. Then I went on to comment on Classical Chinese education because I thought the doodles could be used as a nice piece of teaching material. Below I’ll continue to list three ways that I think can help us modernize Classical Chinese teaching and learning in the 21st century. 😃

Methods

There are presumably many methods we can use to modernize Classical Chinese teaching. Below I list three based on my own experience.

1. Introduce relatable materials

Textbooks normally only include carefully edited classical texts by the best authors, but it’d be cool if students can also see some materials that are less elevated (or totally quotidian) but more relatable, just like the Dunhuang manuscript doodles. Relatable materials can give modern students an idea as to how ordinary ancient people had used their language, which can in turn help them approach classical texts from a more “contemporary” perspective.

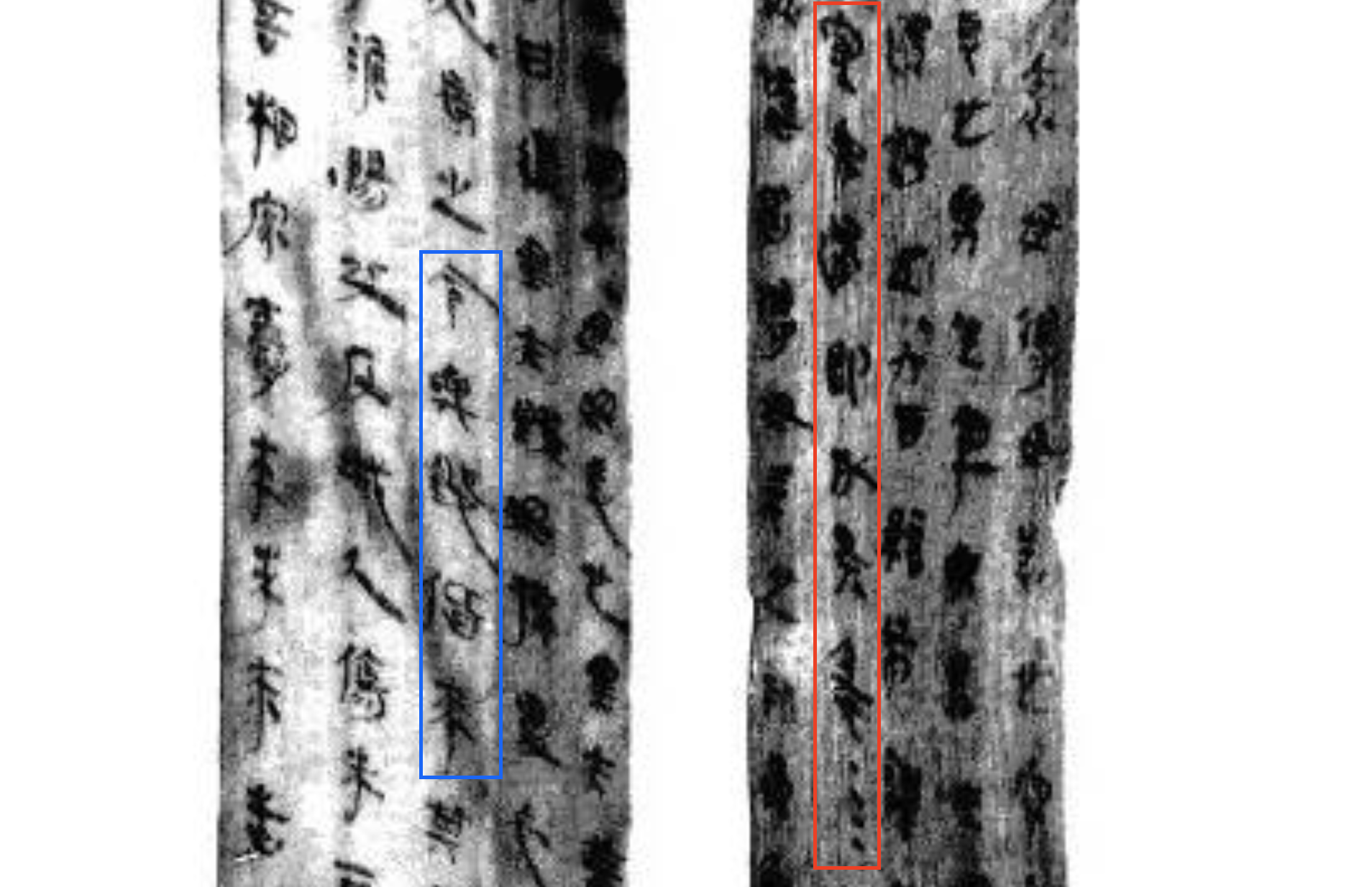

As I’m writing this, another example of relatable material has come into my mind. It’s a Qin-dynasty letter from two soldier brothers to their mother and older brother (written in colloquial Old Chinese in ca. 225 B.C.E.). They greeted their family in the letter but mainly asked for some money and clothes, as the war was getting increasingly brutal. The letter is found in the older brother’s tomb, and it’s the only item found there, which means his two younger brothers had probably never returned home. 😭

2. Reuse TV drama characters

In Part 1 I mentioned two examples of multimodal teaching in Latin classrooms (one in the U.S. and one in my own undergraduate university in Beijing), but multimodality needn’t be limited to occasional movie clips or their original content. Nowadays there’s a multitude of historically themed TV dramas, movies, and video games, and I personally have found them a great aid to studying classical texts on sophisticated political/military matters, because compared to printed names, actual faces are a lot easier to work with in mental reconstruction of complex events. For instance, I used to rely on characters from the Harry Potter movies to aid my reading of the books, which was basically like directing a minimovie in my own head 😂. Of course, one can’t take TV dramas or movies too seriously, for they are fundamentally fictional after all and often make up nonexistent figures and relationships. But I think it’s okay (and very convenient) if we just reuse the faces we need and ignore the fictional aspects.

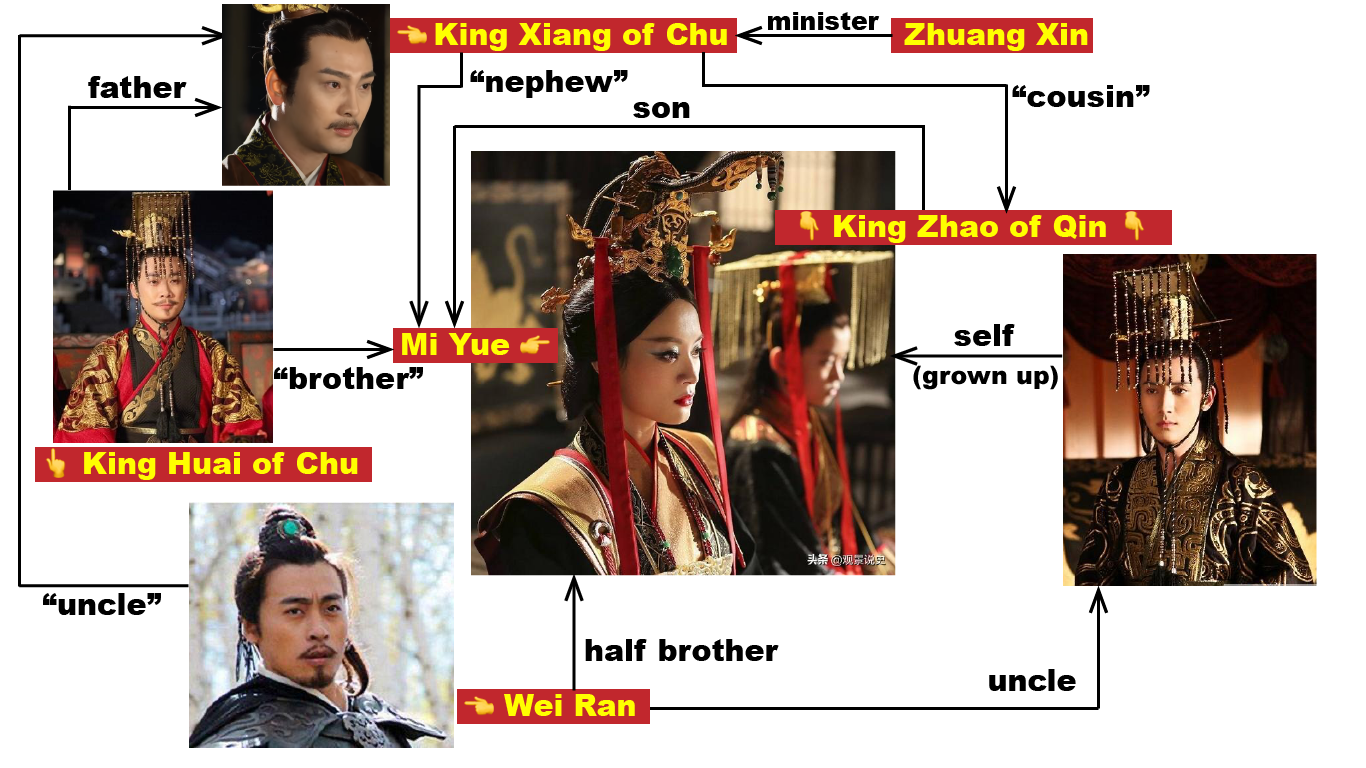

A concrete example in relation to Classical Chinese that comes into my mind is the TV drama The Legend of Mi Yue, which tells the life story of the first Tài Hòu (a title for Queen Dowagers) in Chinese history. It’s quite popular and can be mentally reused when one studies classical texts from the Warring States period. For instance, there’s a pretty dull text in Wang Li’s Ancient Chinese (a most popular university textbook in China) taken from Strategies of the Warring States. The text records how the Chu minister Zhuang Xin persuaded King Xiang of Chu to abandon his harmful lifestyle and protect Chu from the belligerent Qin. As something relatable, the famous four-character idiom wáng yáng bǔ láo (亡羊補牢) ‘better late than never’ has its origin here.

While the text only has two main figures (Zhuang and King Xiang), to properly understand it we must acquaint ourselves with at least three others: King Huai of Chu, King Zhao of Qin, and Wei Ran. Interestingly, four out of the five figures (except Zhuang Xin) are relatives of Mi Yue in the TV drama: King Huai of Chu is her (fictional) brother, so King Xiang of Chu is her (fictional) nephew; King Zhao of Qin is her (real) son, and Wei Ran is her (real) half brother. Thus, those who have watched the TV drama (like me 😅) would be able to quickly grasp this Classical Chinese text (and actually also the next one in the same textbook) in a very vivid way.

3. Learn it as a LANGUAGE

Classical Chinese, like any other classical or modern language variety, is ultimately just a human language; namely, a systematic mapping between sign and meaning. As such, perhaps we should try to learn it in the same way as we learn other languages, which means we should

- pay attention to both reading/translation and writing/production,

- build up a grammatical system rather than just pick up individual grammar points, and

- check out language materials from multiple registers rather than just focus on the elevated, literary register.

I’ll begin with this last point, since my first method above (i.e., introduce relatable materials) is exactly about it.

A register is a variety of language used for a particular purpose or in a particular communicative situation. ...As with other types of language variation, there tends to be a spectrum of registers. Wikipedia

Note that when considering registers we must jump out of the Classical Chinese box (since “classical” itself is already a register) and view ancient Chinese from a broader perspective. As far as I’m concerned, current textbooks used in Chinese schools and universities normally cover the following registers:

- literary (prose, poetry, etc.)

- (semi)colloquial (e.g., dialogs)

- (semi)factual (mostly historical records)

- fiction (e.g., plays, novels)

Registers that are rarely seen in textbooks include:

- science-y (math, geography, chemistry, etc.)

- religious (e.g., Buddhist, Taoist)

- ritualistic (for weddings, festivities, conferrals, etc.)

- legal

- financial

- etc.

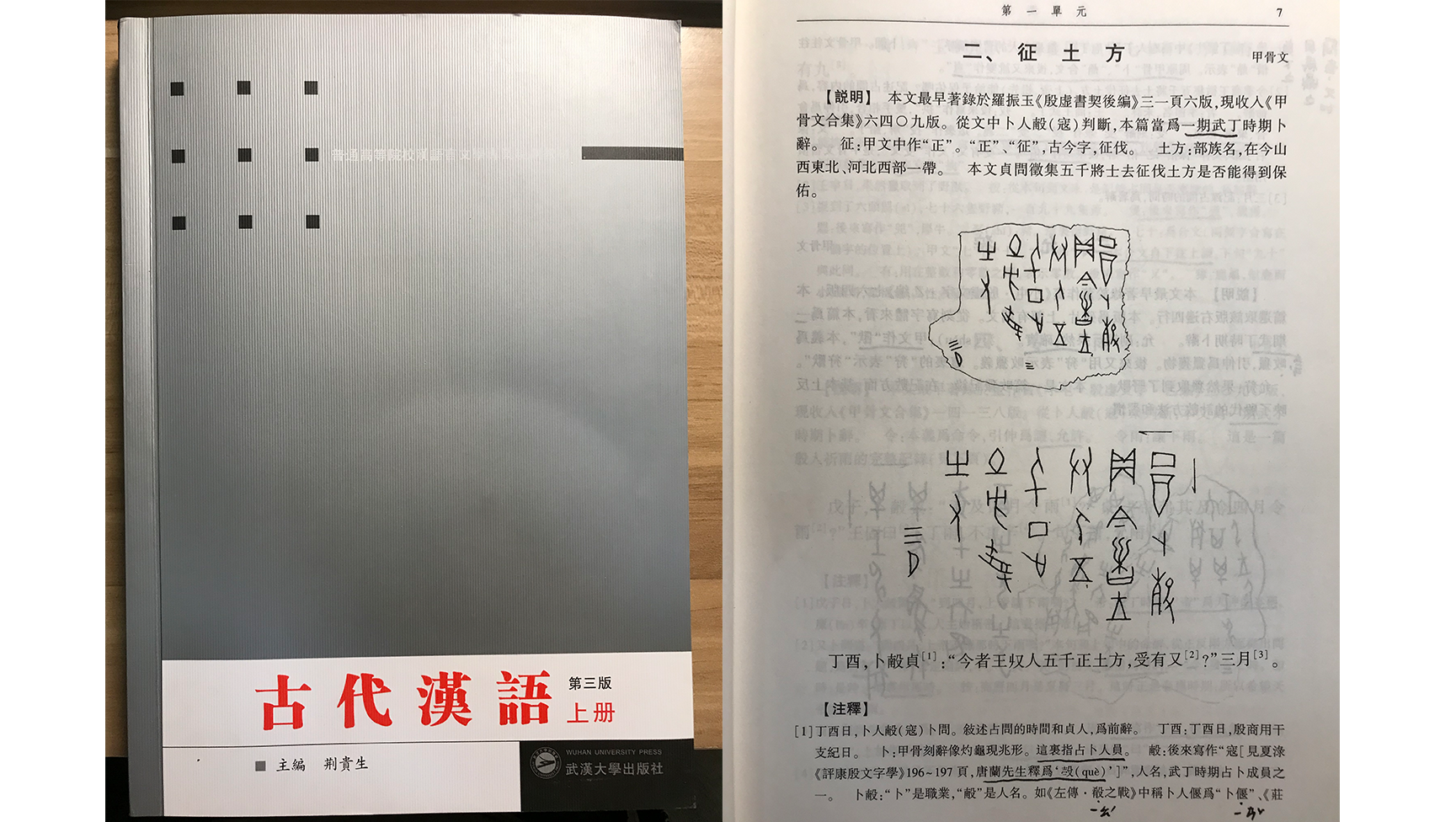

Thus, a textbook that covers any one or more of these additional registers would make a huge difference in the domain of ancient Chinese education. And if the textbook could in addition teach students how to compose their own texts, even just in one or two registers, then it would be the best textbook of the century (as of 2021) 👏. Among all the textbooks published in China I’ve seen, the only one that checks both boxes is Jing Guisheng’s two-volume Ancient Chinese published by Wuhan University Press. In fact it also checks some other praiseworthy boxes, so I highly recommend it to those who can read Chinese. Its latest edition is from 2011 (3rd ed.) but the second edition from 2005 is the most complete or “unabridged” if you ask me.

As for the more linguistic side of Classical Chinese, I think some prior knowledge in general linguistics (especially in syntax) is extremely helpful 💪. I can say from my own experience that Classical Chinese grammar becomes a lot less confusing when explained in general linguistic terms. For example, Chinese textbooks have this oddly formulated term “canceling independence of a clause” (取消句子獨立性), which refers to the function of the particle zhī (之) in sentences like the following (both from high school textbooks):

(1) a. 師道之不傳也久矣

shī dào zhī bù chuán yě jiǔ yǐ

teacher way ZHI not pass.on PRT long.time PRT

‘lit. The not passing on of the way (i.e., tradition) of learning with a teacher has been long.’

b. 不患人之不己知

bú huàn rén zhī bù jǐ zhī

not worry people ZHI not self know

‘lit. I do not worry about other people's not knowing me.’

I’ve seen many complaints about this function of zhī, both in real life and online, because “canceling independence of a clause” as an explanation doesn’t really make much sense unless you already know what it means. That said, the English translations clearly show that this zhī is still used as a genitive marker, as reflected in the underlined of in (1a) and the ’s in (1b), so zhī is not the element that cancels clausal independence but rather a result or reflection of this “canceling” procedure, which in general linguistic terms is just clausal nominalization (or gerundizing). Since students are already familiar with this grammatical phenomenon from their English learning, a lot of confusion can be saved if teachers can replace the above-mentioned Chinese-specific term (which is esoteric) by this more general linguistic term.

Previously I have written about how linguistics can help in foreign language learning. It is equally helpful in classical language learning. In the case of Classical Chinese, I think the following tips may be worth a try:

- In high school, encourage Chinese teachers to borrow familiar terms from English grammar and facilitate communication between Chinese and English teachers more generally.

- In university, encourage students to take a general linguistics course (ideally in syntax) before studying Classical Chinese.

Unfortunately, nowadays most Classical Chinese textbooks written in Chinese are still framed in traditional grammarians’ terminology. Textbooks written in English (e.g., Pulleybank’s Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar) are relatively better since they take an English/Indo-European perspective (see another post of mine for some examples), though that still doesn’t equal a general linguistic perspective. As international and cross-disciplinary communication becomes increasingly common, let’s hope there will be more resources explaining Classical Chinese grammar in the modern linguistic way. So far the only book I know that does this is Mei Guang’s 上古漢語語法綱要 ‘An Outline of Old Chinese Grammar’. As Mei states in the preface to his book:

唯有與當代語言學接軌,古漢語硏究纔有發展,纔有可能開創新局面。

Research on ancient Chinese will only have new developments and make new breakthroughs when it finally catches up with modern linguistics. (my translation)

Mei’s words are mainly about academic research, but I believe the same is true for language teaching.

Final thoughts

In this two-part post I’ve written down some of my thoughts on how we can learn and teach Classical Chinese more efficiently and enjoyably in the 21st century. With all the fancy new tools we have today, which our ancestors could only have dreamed of, maybe the only shackle on our progress is our (lack of) imagination. Human language has a timeless side, so one may surely keep writing articles or poems in ancient Chinese in 2021 (as long as they are equipped with the essential linguistic skills). Human language also has a universal side, so one may surely learn Classical Chinese via a general linguistic route or even develop a “generative grammar” for it. I wish there will be more resources exploring both sides in the future—ideally with open access. 😁

Leave a comment