Recently I was having this conversation with a (hyper)polyglot friend—who had already inspired a post on this blog by the way—where we exchanged ideas on various Chinese language textbooks. At some point during the chat I suddenly remembered a very old textbook from early 19th century that I had seen not long ago. Then, another idea popped up in my head: Why not write a blogpost on old Chinese textbooks? So here it is. 😃

Preface

In this multipart post I’ll share my personal impressions of four 19th-century Chinese textbooks. They had all been written by Europeans for Europeans, so their general approach and terminology are also European. I know of an old grammar book written by a Chinese for Chinese as well—the famous Mashi Wentong ‘Ma‘s Grammar’ (Ma Jianzhong 1898)—but I won’t include it here as it’s not really a textbook (but a linguistic treatise).

Besides, I’ve read two textbooks written for Korean people learning Chinese but won’t include them in this post either (despite their high popularity in history), because they had been written much earlier (in the 14th century!). If I attempt to review each and every historical Chinese textbook out there then this post will probably never finish. 😝

Therefore, I’ve decided to limit my scope to only 19th-century textbooks written by Western authors, hence my selection of the following works:

| Title | Chinese title | Author (surname) | Year | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of Chinese Grammar | 中國言法 | Marshman | 1814 | English |

| A Grammar of the Chinese Language | 通用漢言之法 | Morrison | 1815 | English |

| A Progressive Course of Colloquial Chinese | 語言自邇集 | Wade | 1867 | English |

| Chinesische Grammatik | 漢文經緯 | von der Gabelentz | 1881 | German |

I like some of these works better than the others in one way or another, but they all strike me as very different from textbooks today. In what follows I’ll review and rate them (in the above order) based on three main components of their pedagogical content: pronunciation, Chinese characters, and syntax.

Note: Throughout this post I use “syntax” in a broad sense, which includes both syntactic rules and the syntactically relevant part of the lexicon (e.g., function words, word categories). In particular, I view word formation rules as syntactic rules. Modern syntacticians, at least those of us working in generative grammar, care as much about word structure as we care about sentence structure.

There isn’t a separate dimension of vocabulary in my review because none of the four textbooks really teaches vocabulary—like how to say “apple” and how to saw “tree”—in a progressive way. Maybe students in the 19th century were supposed to study vocabulary on their own with a dictionary? On that note, the two 14th-century textbooks mentioned above do have a highly detailed vocabulary component; for example, Nogeoldae uses several full pages to teach horse-related words 🐎. Maybe here lies an East vs. West difference to some extent. Apparently Asian students love vocabulary learning! 😂

1. Elements of Chinese Grammar

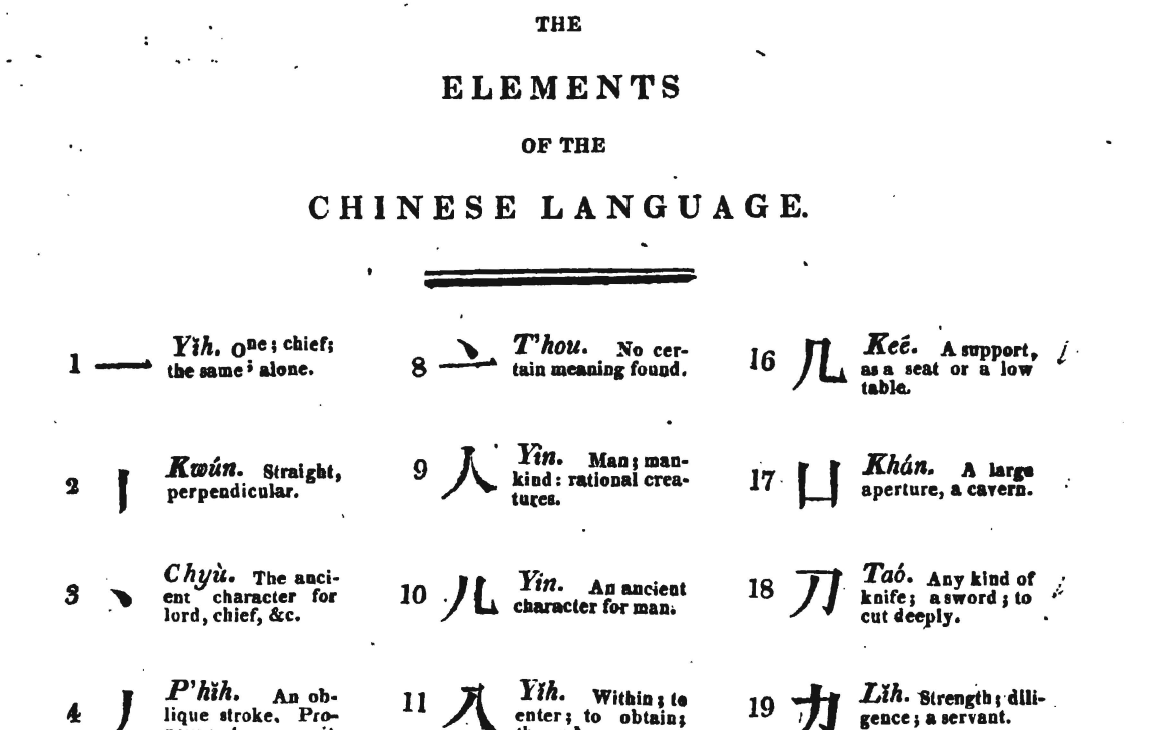

The earliest 19th-century Chinese textbook I’ve seen is Joshua Marshman’s (1814) Elements of Chinese Grammar (henceforth Elements), or 中國言法 in Chinese. Marshman (1768–1837) was a British Christian missionary to India who was also very interested in China. He studied the Chinese language for a couple years and devoted much of his time to translating between English and Chinese texts, such as the Analects and the Bible. The motivation behind this textbook had precisely come from his translation work.

On completing the first volume of Confucius … it seemed desirable that it should be accompanied by some account of the language. (Elements, Preface)

This book is freely available on Google Books.

Character part

Rating: ★★★★✦✧ (✦✦=★)

A clear highlight of Marshman’s textbook, which is also a feature that I personally adore, is its emphasis on Chinese characters. It dedicates 80 pages to them before everything else!

In a language which differs so entirely from all others, it seemed impossible to do justice to either its Written or Colloquial medium, within the space generally allotted in other grammars to the letters …. To the author they seemed to deserve a separate essay. (Elements, Preface)

Scholarly tone

Moreover, these 80 pages are actually a self-contained theoretical discussion of the Chinese writing system rather than a user guide. Thus, it doesn’t really teach how to write each stroke by hand, which stroke to write first, etc. or give any hand-writing homework (probably because those are better done by an instructor anyway) but is more focused on scholarly issues like the origin of Chinese characters, the principles of their formation, and so on. For instance, it introduces the six structural classes of Chinese characters with detailed illustration.

The Third class [is] termed Tcheé-sheè, “indicating the thing.” … These characters, though not pictures of things, seem intended to suggest ideas to the mind from their form and position. …To this class, which we may term the Indicative, is said to belong 本 pún, which is formed by drawing a short stroke across the middle stroke of 木 moǒh, wood, and which then denotes the root, essence, or internal part of any thing. (Elements, p.21)

Note: Here and below, when [and only when] citing original words from historical textbooks, I keep their original romanization forms, which are not in the currently standard pinyin system and shouldn’t be misunderstood as such.

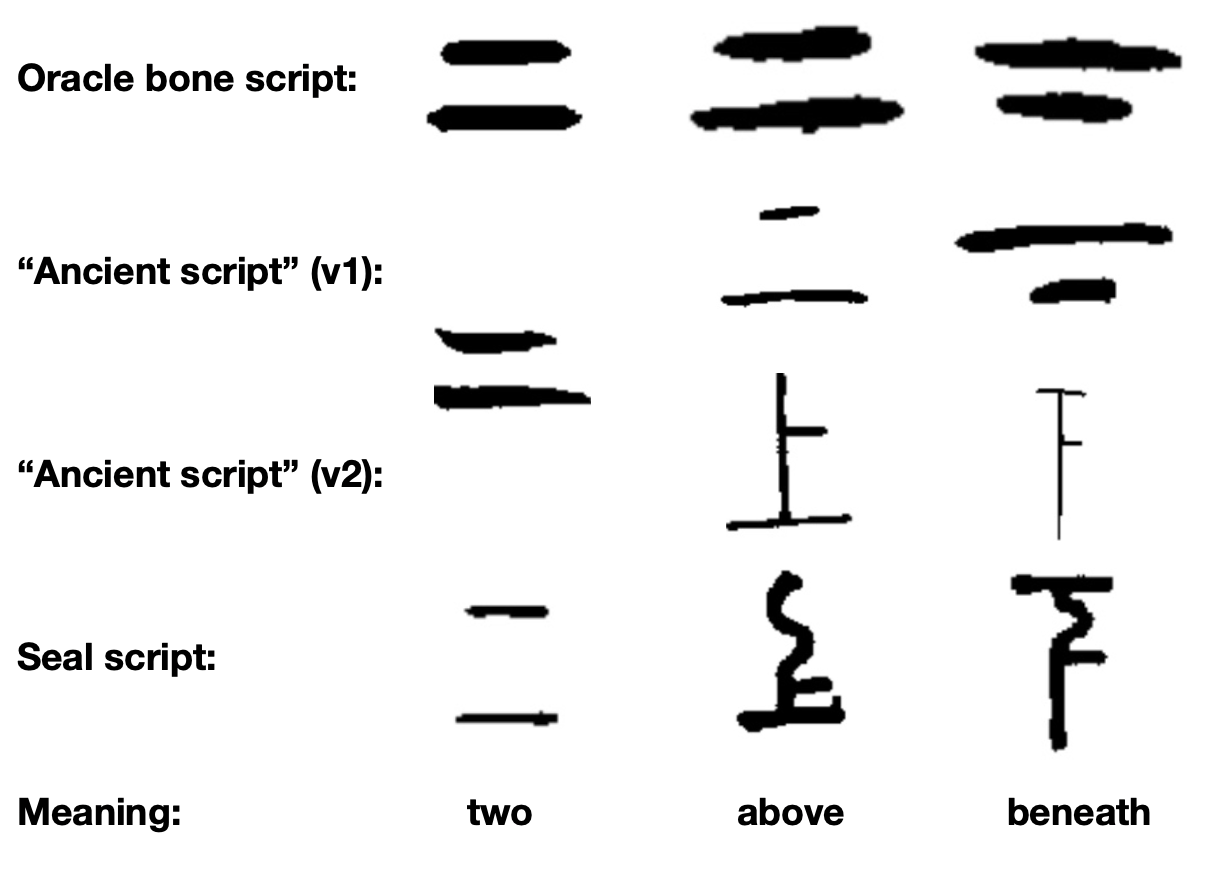

It must be pointed out that some of the character analyses in the book are wrong. For example, Marshman analyzes 上 shang4 ‘above’ and 下 xia4 ‘beneath’ as consisting of a (distorted) person shape (人 ren2) positioned above and below a horizontal line, when in fact there’s no person shape in the two characters. The short horizontal/oblique strokes actually serve to indicate the space above/beneath the horizontal stroke instead, and the vertical stroke serves to distinguish these two characters from 二 er4 ‘two’.

Despite glitches like this (How many textbooks are totally error-free anyway?) I still think the character part of Marshman’s textbook is a highly valuable piece of learning material. Among others, it contains a fully glossed list of the 214 basic building blocks (aka the 214 radicals) for Chinese characters from Kangxi Dictionary, the official Chinese dictionary during the 18th–19th centuries. The list is also useful to native speakers (e.g., elementary school students) because nowadays not many Chinese people can pronounce all the radicals or explain their meanings.

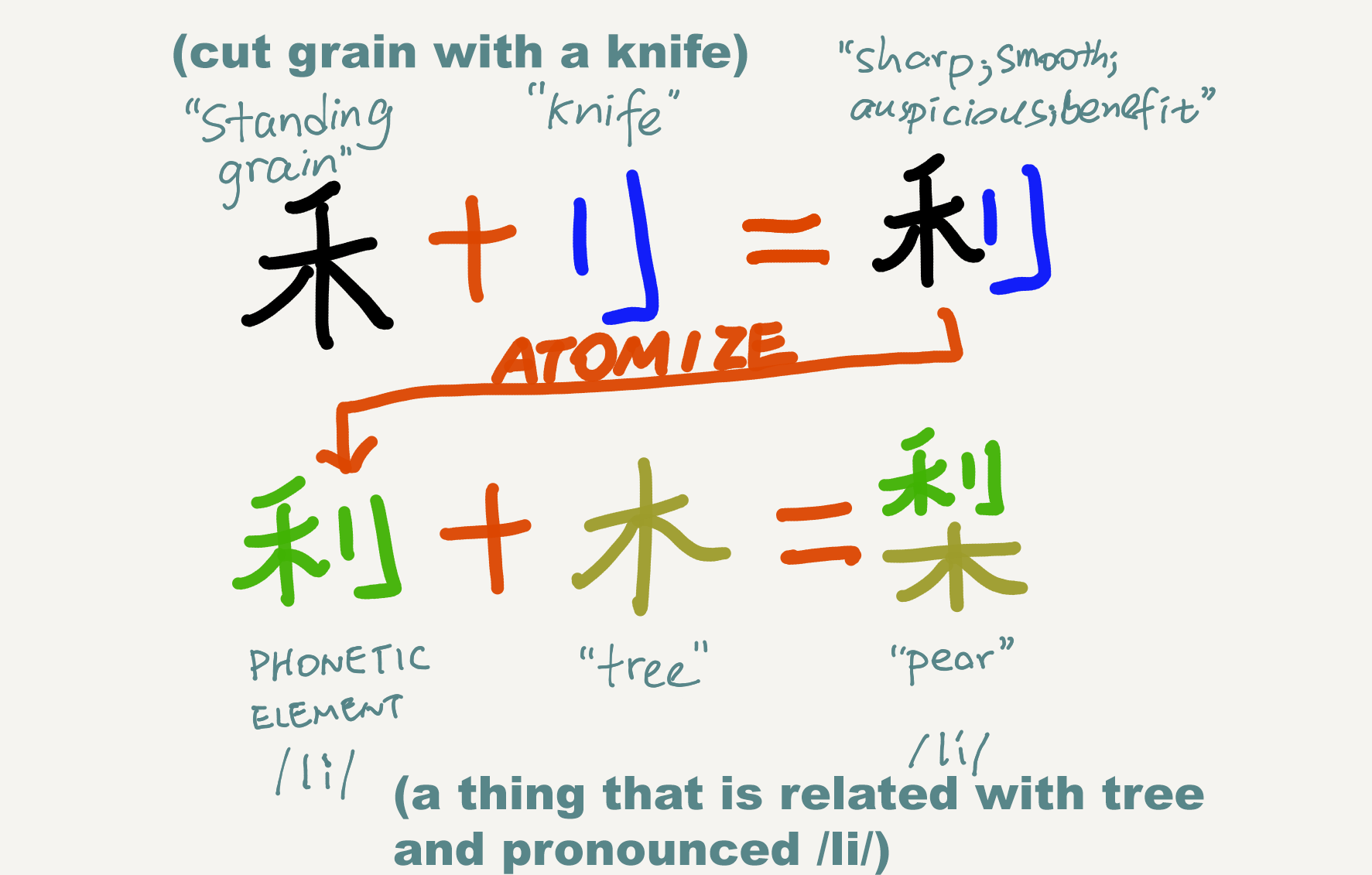

Recursive character formation

Another feature of Marshman’s textbook that I like is its discussion on the recursive nature of character formation. That is, after two radicals A and B have been combined to form a character C, this compound character can in turn serve as a new quasi-radical—or an “atomized” structural unit, so to speak—and combine with another radical D to form a new compound character E. Marshman presents four levels of recursion in his book. An interesting research question is whether four is the limit of the mechanism.

Marshman furthermore compares recursive character formation with recursive compound word formation. His original examples are from Greek (p.72), but we can also easily find examples in English, such as vanilla ice cream and high school student. From a modern linguistics perspective, even though one can’t say that recursion in character formation and that in word formation are one and the same phenomenon, it is obvious that some common cognitive strategy is at work, which in my opinion isn’t so different from what Noam Chomsky calls a “third factor” in human language design.

Pronunciation part

Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

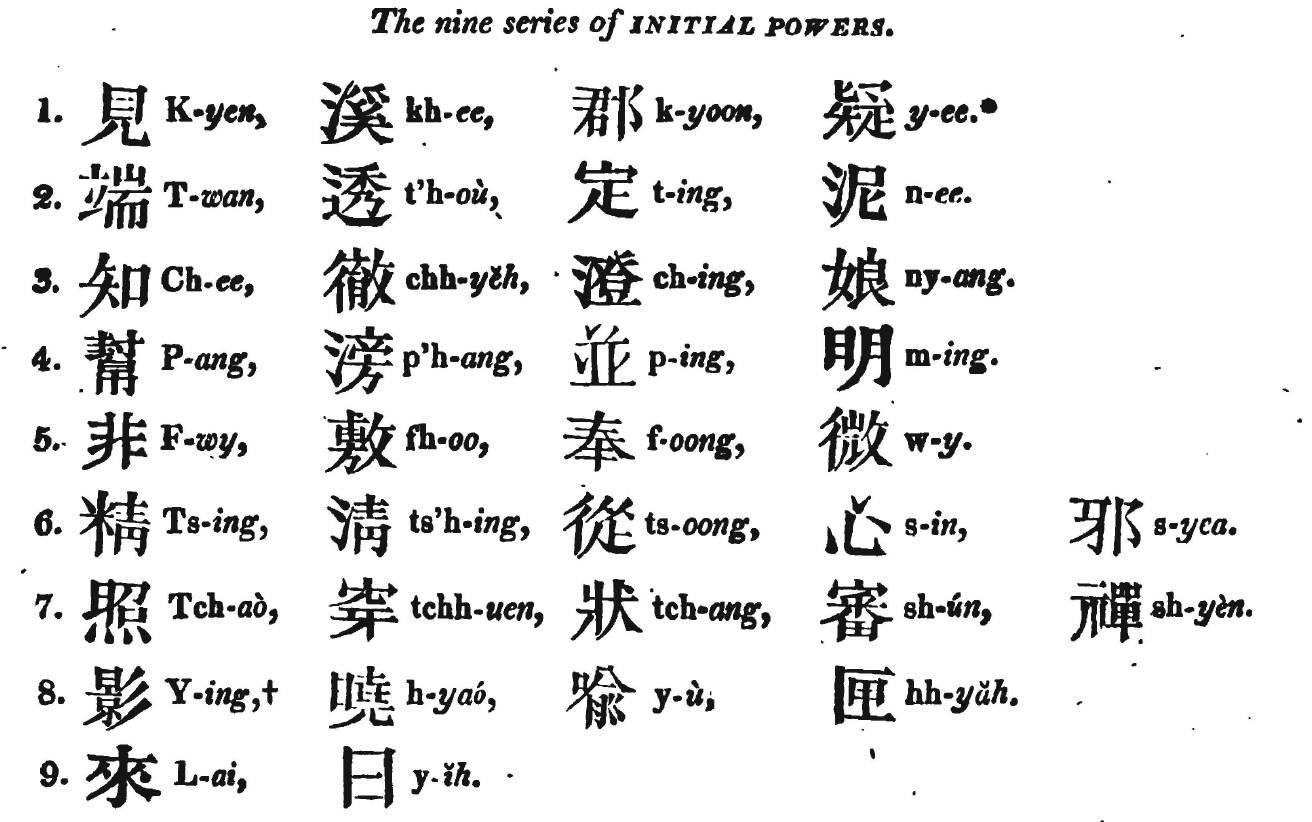

After teaching the basic building blocks and formation principles of Chinese characters, Marshman continues to teach their pronunciation. He mainly teaches the Beijing accent but has a section on Cantonese as well (entitled “Of provincial variations”). Marshman follows the phonological system in Kangxi Dictionary, which is much more ancient-looking than pinyin because it notates all relevant phonological features and symbols by Chinese characters—hence the necessity of a romanized transcription for European students.

I can’t say Marshman’s romanization system is my favorite. Among others, its mixture of uppercase and lowercase letters is confusing (and can be easily messed up in practice), and so is its inconsistent and not always logical usage of h (e.g., that in fh and that in hh). Besides, a general dissatisfaction I have with the pronunciation part of the textbook is its ambiguity on some important notions that were already common sense among Chinese scholars of the time.

One clumsily introduced phonological notion is voiced consonant, and another one is unreleased final stop (aka the entering tone). While both features had more or less vanished from Beijing Mandarin in the 19th century, they were still deemed an important part of traditional Chinese phonology and therefore shouldn’t be glossed over in a pedagogical text like this one.

Also, I don’t think the lack of clarity here was due to Marshman’s ignorance of the relevant linguistic facts—he did know Sanskrit quite well and apparently also knew some Cantonese, both of which had clearly inspired him on these issues.

But what is the third sound [i.e., the third column in the consonant table]? And wherein does it differ from the first? These are questions to which I have never been able to obtain a satisfactory answer. …If we examine the Sungskrit alphabet, to which the Chinese system bears a surprising likeness, we shall find, that … their third sound is … softened: thus … k-u is softened to g-u. (Elements, p.90)

[The fourth tone] has a peculiarity which the other three have not; it in some degree alters the syllable, and causes it to terminate in an obscure sound something like that given in English to a final h … and which … in certain of the provincial dialects, is carried forth so as to end in k, t, or p. (Elements, pp.174–175)

Note: In traditional Chinese phonology the fourth tone refers to the entering tone (入聲) instead of the falling tone (去聲). The latter is called the third tone. The tones are numbered differently in Modern Chinese.

Seeing the above quotes, I feel like Marshman did have an idea of what was going on but somehow ended up presenting this section in a more confusing than illuminating way. So, if you want to read about traditional Chinese phonology or just about 19th-century Chinese pronunciation, I wouldn’t recommend Marshman’s textbook as a first choice. 👀

Leave a comment