Quick links:

Tutorial Day notes:

- Lecture 1: Introduction to applied category theory (David Spivak, video)

- Lecture 2: An introduction to string diagrams (Fabrizio Genovese, video)

- Lecture 3: The Yoneda lemma in the category of matrices (Emily Riehl, video)

- Lecture 4: Monads and comonads (Paolo Perrone, video)

In this third lecture by Emily Riehl entitled “The Yoneda lemma in the category of matrices,” we are shown a particular use of the Yoneda lemma. Emily has put her slides online, so in this post I won’t repeat the bulk of the content that is already in there. I’ll just note down my personal understanding of the example instead, which might be useful to category theory learners who are as “ignorant” in matrix theory as I am (I have no prior knowledge at all 😧).

So, Emily first commented that the Yoneda lemma was everywhere and like a magic tool, though she also acknowledged that it was very hard for beginners and that the understanding of it could be a long, slow process. Then she went on to introduce the category $\mathbf{Mat}$ of matrices, whose objects are natural numbers and morphisms are matrices. She used this category to illustrate how the Yoneda lemma could be used in mathematics.

I don’t know matrix theory at all (nor do I know much about linear algebra), and even though now I understand the most basic definitions after a quick Google search, I’m still far from ready to learn something as mind-boggling as the Yoneda lemma through it. But an important merit of category theory is that it is so abstract and general that you don’t really need to know much about a particular subject in order to understand the application of basic category-theoretic ideas in it—as long as the application itself is correct (which is incumbent on the researcher to guarantee, of course), you just need to substitute or “localize” a few things, and the rest will become self-evident.

(Disclaimer: The general convenience of category theory is not an excuse for us to stop learning particular subjects! I should stop being lazy and start catching up on my higher math knowledge.)

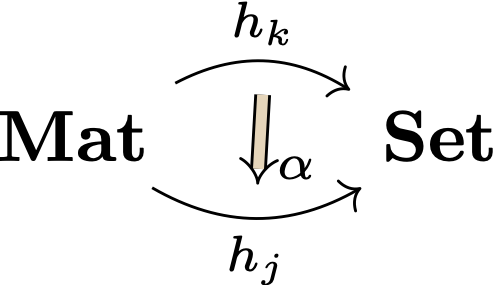

So, below is my personal understanding of how the Yoneda lemma is used in the matrix category. First off, Emily’s basic categorical setting involves $\mathbf{Mat}$, $\mathbf{Set}$, and two functors between them: a particular “$k$-column functor” $h_k$ and another (presumably randomly picked) “$j$-column functor.” There is a natural transformation $\alpha$ between the two functors, which is interpreted as a “naturally-defined column operation” that transforms matrices with $k$ columns into matrices with $j$ columns. I illustrate this setting with the diagram below:

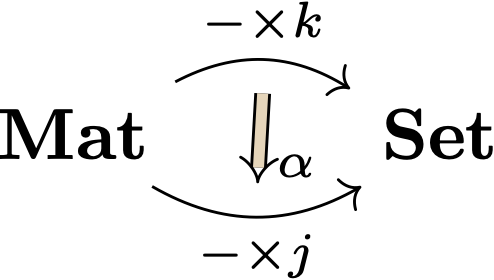

Now, what the $k$-column functor (and similarly the $j$-column functor) does is that it fixes the column number of a matrix as $k$ and lets its row number vary. Thus, for each possible row number $n$ as input it will yield a particular set of $n\times k$ (convention: row $\times$ column) matrices as output—this is just the hom-set between the $\mathbf{Mat}$-objects $k$ and $n$ in categorical terms. So, $h_k$ as a functor can effectively be rewritten as “$- \times k$,” where “$-$” is the blank placeholder (like an unnamed variable) conventionally used in category theory. Similarly, $h_j$ can be rewritten as “$-\times j$.” For some reason I find this alternative notation easier to understand, maybe because it’s more transparent in terms of what the functors do. So, we can now redraw the above diagram as follows:

Under this setting, Emily’s question was: How to describe all natural transformations of the form $\alpha$? Namely, how to classify all naturally-defined column operations that transform matrices with $k$ columns into matrices with $j$ columns?

This is exactly the kind of question that the Yoneda lemma is going to answer. (ER)

The solution she gave out was the following:

- Every naturally-defined column operation $\alpha: h_k \rightarrow h_j$ is determined by a single $k\times j$ matrix.

- This $k\times j$ matrix $\alpha_k(I_k): j\rightarrow k$ is obtained by applying the column operation $\alpha_k$ to the identity matrix $I_k: k\rightarrow k$.

- The column operation $\alpha_n: h_k(n)\rightarrow h_j(n)$ is then defined by right multiplication by the matrix $\alpha_k(I_k):j\rightarrow k$.

Well, I don’t understand matrices but do know something about the Yoneda lemma, at least about its definition and basic mechanism. The following textbook definition is directly copied from this previous blog post of mine:

Yoneda lemma: Let $\mathbb{C}$ be locally small. For any object $C\in\mathbb{C}$ and functor $F\in\mathbf{Sets}^{\mathbb{C}^{op}},$ there is an isomorphism \[ Hom(yC, F) \cong FC \] which, moreover, is natural in both $F$ and $C.$ (Category Theory, pp. 188–189)

The Yoneda functor (aka Yoneda embedding) is defined as follows:

The Yoneda embedding is the functor $y\colon \mathbb{C}\rightarrow\mathbf{Sets}^{\mathbb{C}^{\mathrm{op}}}$ taking $C\in\mathbb{C}$ to the contravariant representable functor \[ yC = \mathrm{Hom}_\mathbb{C}(-,C)\colon \mathbb{C}^{\mathrm{op}} \rightarrow \mathbf{Sets} \] and taking $f\colon C\rightarrow D$ to the natural transformation \[ yf = \mathrm{hom}_\mathbb{C}(-,f)\colon \mathrm{Hom}_\mathbb{C}(-,C)\rightarrow\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbb{C}(-,D), \] … One should thus think of the Yoneda embedding $y$ as a “representation” of $\mathbb{C}$ in a category of set-valued functors and natural transformations…. (Category Theory, p. 187)

Now things become clearer. The category $\mathbb{C}$ in the definition of the Yoneda lemma is just $\mathbf{Mat}$ in Emily’s example, and the hom-set $\mathrm{Hom}(yC, F)$ is just the desired set of natural transformations (i.e., column operations) in Emily’s question. This means that $yC$ is the given $k$-column functor and $F$ is the other random $j$-column functor. Since $y$ is the Yoneda embedding functor, which sends a $\mathbb{C}$-object $C$ to the representable functor $\mathrm{Hom_\mathbb{C}}(-,C)$, we can suitably identify $C$ with $k$ in the category $\mathbf{Mat}$, because $\mathrm{Hom_\mathbb{C}}(-,C)$ looks like $\mathrm{Hom_\mathbf{Mat}}(-,k)$, which is just $-\times k$ (i.e., a matrix with $k$ columns and an unknown number of rows).

So, now we have substituted both $F$ and $C$ in the definition of the Yoneda lemma with data in Emily’s example. The Yoneda lemma says the desired set of natural transformations is determined by $FC$, which is just $-\times j(k)$, namely $k\times j$, in the matrix example. This is exactly the “single matrix” mentioned in Emily’s solution (Step 1). As to the peculiar-looking column operation application $\alpha_k(I_k)$ in Step 2, it doesn’t show up in the definition of the Yoneda lemma but corresponds to a particular function in the detailed calculation (see another previous post of mine).

Anyway, I think the real key step in our understanding of the connection between the Yoneda lemma and the matrix example is Step 1. Once we get the connection, we immediately get how the lemma is applied in this very example—and that is no doubt a brilliant application!

Leave a comment