In the previous four posts I organized my notes from the ACT2020 Tutorial Day. In this post I’ll continue to note down things I’ve learned from the main sessions. I’ll keep updating this post till the end of the conference.👨💻

Quick links:

Tutorial Day notes:

- Lecture 1: Introduction to applied category theory (David Spivak, video)

- Lecture 2: An introduction to string diagrams (Fabrizio Genovese, video)

- Lecture 3: The Yoneda lemma in the category of matrices (Emily Riehl, video)

- Lecture 4: Monads and comonads (Paolo Perrone, video)

Since most talks employ advanced category-theoretic techniques and are about subjects I’m not familiar with, I won’t attempt to recap their results. I’ll merely make a list of the concepts that I repeatedly heard at the conference instead, which will serve as a learning agenda for myself.

Days 1–2

(Unfortunately I had to miss a good part of Day 2 due to a clash, but fortunately all talks have been made available on YouTube, so I have managed to catch up.)

Petri net

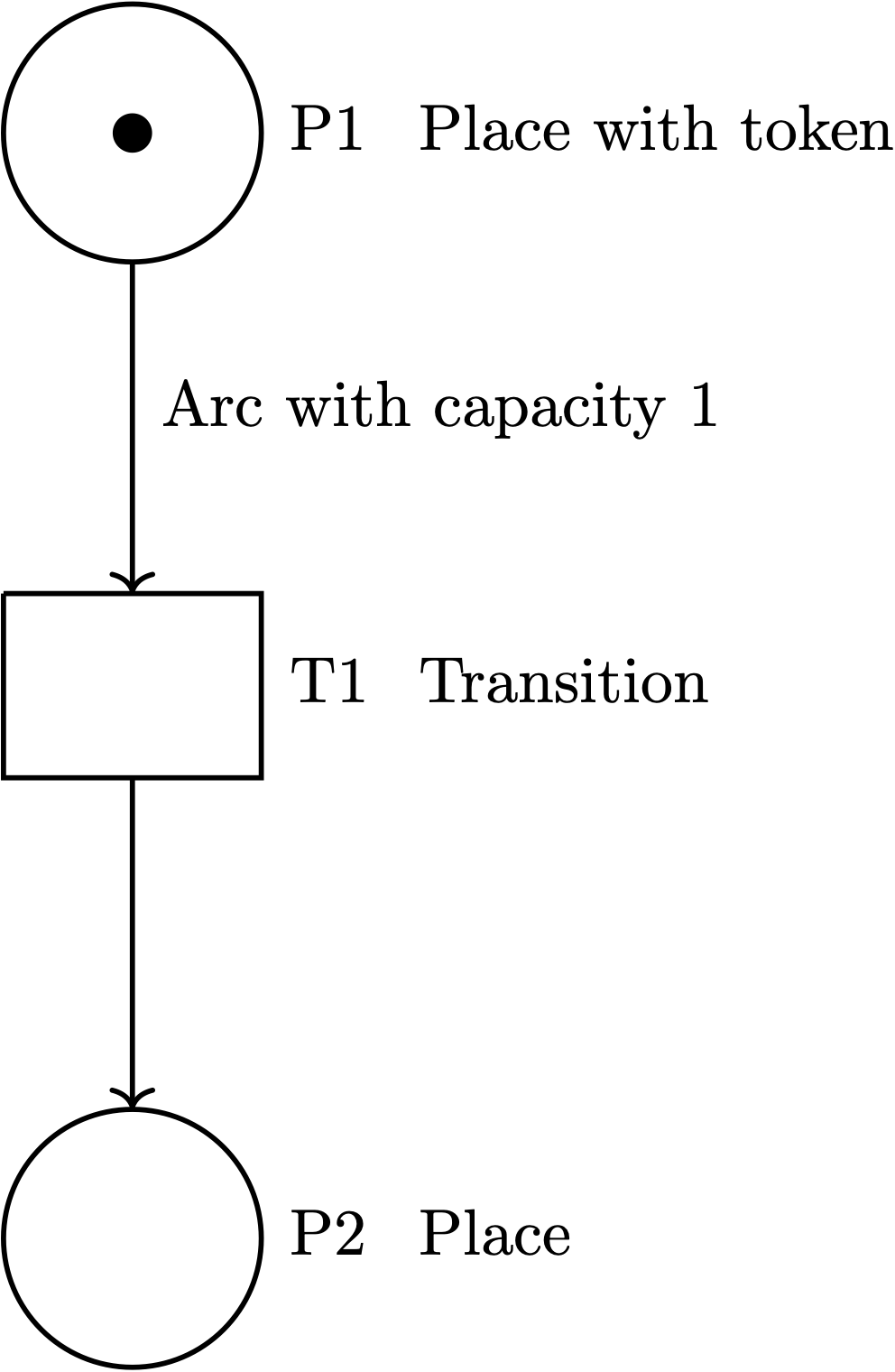

The first talk on Day 1 was about “Petri nets,” and several other talks on the same day were also centered on this concept. I had seen this term before—probably also in the context of ACT—but had never engaged with it, because it felt so far-away from my own subject. This time I googled a bit and acquainted myself with its basics. I’ve found this web page from Bielefeld University and this blog post by John Baez easy to follow. The picture below is a Petri net:

a Petri net (adapted from the Bielefeld University website)

A petri net, as Wikipedia puts it, is mathematically a directed bipartite graph. It consists of circles called places and rectangles called transitions. Places hold tokens and arcs have capacity numbers. Here when $T1$ “fires,” the single token in $P1$ will be transmitted into $P2$.

Apparently Petri nets are widely used throughout science, and the Petri net–related talks all aim to propose category-theoretic structures to efficiently model them. The basic idea seems to be that a certain kind of free category can be generated from the data of a Petri net, which in turn extends to a functor from a category of Petri nets to a category of categories. The freely generated category has a particular type of monoidal structure. Two recent papers by John Baez and his student Jade Master contain more detail (1, 2):

- Master (2019). Generalized Petri nets.

- Baez & Master (2020). Open Petri nets.

system theory

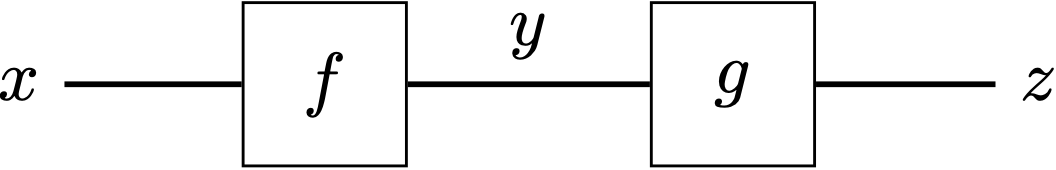

I learned from the conference that “categorical system theory” was an established area of study. There are perhaps more than one way to examine systems categorically, and there are surely multiple types of system as well. Jules Hedges’ talk focused on “open systems,” which are viewed as categorical morphisms. Boundaries between those systems, on the other hand, are viewed as objects. (PS: This feels a bit counterintuitive to me.) Under this setting, composing morphisms is just connecting boundaries, which Hedges illustrated with the following string diagram:

Here the composite system $g\circ f$ is formed by joining the shared boundary $y$. I hadn’t paid much attention to system theory before but might take a look at it later. One thing I’m curious about is what the extension of the term “system” is in the context of categorical system theory. Does it only cover situations where multiple systems interact with one another or are sole systems without external interaction also included? I’m guessing the latter type of system might not be as interesting to category theorists as the former type because of its lack of intricate compositionality.🤔

optics

I noticed that quite a few talks in the conference program had a “lens” in their titles. I didn’t know what it meant and naively wondered whether it was about physics and glasses 😅. But it turned out that both “lens” and “optics” were just metaphors describing certain programming concepts. This blog post by Chris Penner has a detailed illustration of those concepts as they are used in Haskell (the author also has a nice-looking book on the topic), and this blog post on the n-Category Café takes a more category-theoretic approach.

Simply put, optics are a family of data accessors in functional programming. They come in various subtypes, including lenses, prisms, and so on. Take lenses for example, they can retrieve subparts of some given data, update them, and then insert them back in place. To illustrate, the above-mentioned blog post uses postal addresses as a real-life example:

\(\mathrm{viewZipCode}: \mathrm{Postal} \rightarrow \mathrm{Zip}\)

\(\mathrm{updateZipCode}: \mathrm{Postal} \times \mathrm{Zip} \rightarrow \mathrm{Postal}\)

The above functions say that we can a) single out the zip code from a postal address to view it, and b) update the zip code (i.e., replace it with some other zip code) and thereby get a new postal address. This process is mathematically modeled by two maps (Riley’s formulation):

\(\mathrm{Get}: S\rightarrow A\)

\(\mathrm{Put}: S \times A \rightarrow S\)

Here $S$ is the ambient data (e.g., an entire postal address) and $A$ is the subpart of it that gets manipulated via the lens (e.g., the zip code part of the postal address). I guess the term “lens” might have been chosen because this process feels like inspecting the internal structure of the ambient data through a peephole?

The techniques used in the categorification of optics (e.g., end, profunctor) are fairly advanced (see this blog post by Bartosz Milewski for a patient introduction), and I don’t think I can hope to understand them anytime soon. But I’ll come back and update this part if I eventually manage to conquer them someday.

monoidal category

If I were allowed to list only one takeaway message from ACT2020, it is that monoidal categories are everywhere in applied category theory. For instance, each of the three aforementioned disciplinary concepts involves some variant of monoidal category.

I don’t think this necessarily means one cannot do applied category theory without using monoidal categories. I, for one, didn’t use it in my poster. It could just be that most people in the ACT community happen to have a shared interest or come from subject areas where monoidal patterns are commonly seen—basically whenever you do combinatory stuff there’s a chance that you’re dealing with monoidal structures (in a sense “monoidal” just means combining things in parallel, in whatever way the context defines). And so far I haven’t found monoidal categories useful in my own work simply because I’m not doing combinatory stuff—monoidal categories pop up in linguistics too if we turn to address the combinatory side of language, as evidenced by categorial/pregroup grammars (I’ll come back to categorical linguistics below).

Anyway, if one wants to get the most out of their ACT experience, knowing the basics of monoidal categories is a must. Unfortunately beginner-friendly tutorials in this area are hard to find (I might try and compose one if I ever lay my hands on a sequel to my Category Theory notes series 😛). As I mentioned in my notes from the Tutorial Day, monoidal categories aren’t usually taught in elementary textbooks. Fong & Spivak do teach them with crossdisciplinary examples in their ACT textbook, but those are only helpful to the extent that one is familiar with the relevant disciplines (e.g., you wouldn’t find examples from physics or engineering illuminating if you don’t have previous knowledge of these subjects). So far the most patient and comprehensive introduction to monoidal categories I’ve seen is Baez & Stay’s 73-page manuscript entitled “Physics, topology, logic and computation: A Rosetta Stone,” but again I might only have found it good because I happen to know something about logic and computation…

So, perhaps category theory isn’t really a theory for anyone and everyone at the end of the day. The truth is, the more STEM background you have, the easier it is for you to understand the quintessential/motivating examples and thence the categorical concepts. I’d be surprised (in a good way) if one day someone decides to write a textbook for true outsiders, say first-year undergrads majoring in literature or history. That’d be a nontrivial pedagogical achievement in ACT and I’d definitely write an exuberant review of it.😎

Days 3–5

quantum theory

I have no previous knowledge about quantum mechanics, so talks on that were just impenetrable to me. That being said, I did get a general impression of how category theory was put to use in this increasingly popular area. Typically the application is done via some special vector spaces called Hilbert spaces, which form the objects of a category $\mathbf{Hilb}$. The morphisms of this category are a special kind of maps or transformations between Hilbert spaces, which are called bounded linear maps as I’ve learned from Heunen & Vicary’s (2019) book Categories for Quantum Theory: An Introduction.

Apparently Hilbert spaces can be tensored, which isn’t surprising considering the notion tensor had emerged in the context of vector spaces in the first place. Thus, monoidal categories become relevant again, and so are string diagrams. This makes categorical quantum theory in a sense similar to categorical linguistics—and people (such as Bob Coecke) have indeed connected the two (see also this page). (PS: Coecke also has some lecture notes entitled “Kindergarten quantum mechanics”) I am not (yet) in a position to say how successful this approach is from a linguistics perspective, partly because linguist-linguists and NLP-linguists have quite different standards of success, but it does seem to be highly effective in what it’s designed to do.

game theory

I had never thought of game theory from a categorical perspective before—not that I knew a lot about this subject, but prototypical game-theoretic concepts like utility and Nash equilibrium just felt too far away from category theory in my eyes. For example, what could the objects be? A game isn’t a static thing after all. Nor could I think of motivations of caring about “morphisms” between games. As such, the whole point of having a category of games just wasn’t clear to me (though I did find a manuscript online proposing exactly that). The kind of categorical game theory promoted in ACT takes a rather different route, where the key notion is that of an open game. Again here the categorification mainly relies on monoidal categories and string diagrams, though my personal impression is that categorical game theory is merely concerned with a subpart of classical game theory rather than its whole. Two key readings in this area of study are:

- Ghani et al. (2018). Compositional game theory.

- Hedges (2016). Towards compositional game theory.

python

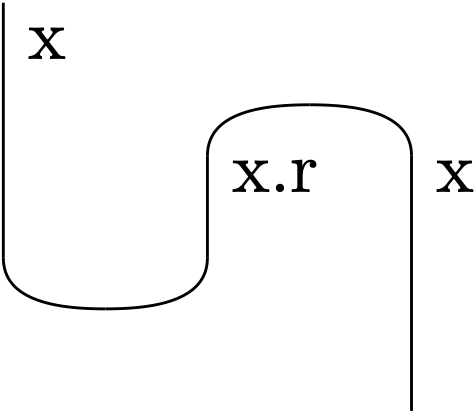

One or two talks at the conference (presumably by members of the same research group) were about the implementation of category-theoretic ideas in the programming language python. The specific package being introduced was called DisCoPy, aka Distributional Compositional Python. It has been developed mainly to facilitate computation with monoidal categories and string diagrams. For example, the following string diagram (which is a slightly modified subpart of the first diagram on the package website) can be produced with just a few lines of code:

from discopy import Ty, Box, Id, Cup, Cap

x = Ty('x')

snake = Id(x) @ Cap(x.r, x) >> Cup(x, x.r) @ Id(x)

# draw the diagram in png format

# snake.draw(path='act2020-5-4.png')

# convert the diagram into TikZ code

# The above diagram is produced by DisCoPy + LaTeXiT

snake.draw(path='act2020-5-4', to_tikz=1)

The code isn’t hard to understand even if we don’t know the category-theoretic definitions of cups or caps (they have to do with dual objects in monoidal categories by the way; see also this page for a profunctor-based explanation). Here Id(x) just tells the computer to draw a vertical line (from the top down) labeled “x,” Cap(x.r, x) draws a “∩”-shape (which looks like a cap) whose two legs are labeled “x.r” and “x,” and A @ B simply indicates that A and B should be drawn side by side. The top-down direction of string diagrams is conventional in categorical linguistics as I’ve mentioned in my Tutorial Day Lecture 2 notes.

Currently the main usage of this python package is in categorical NLP, as its main developer (Alexis Toumi) is from Bob Coecke’s group mentioned above, but it should be useful for a much wider range of subjects given the predominant role of monoidal categories and string diagrams in ACT. As for myself, I think it can at least be a good extension of TikZ as a string diagram–drawing tool, because it has the functionality of converting a string diagram into TikZ code (via the optional draw argument to_tikz), and then we can embed the diagram in LaTeX in a fully fine-tunable format (e.g., I’ve adjusted the positioning of the labels in the above diagram in this way). I’m glad that I’ve learned about the package from the conference.👏

categorical linguistics

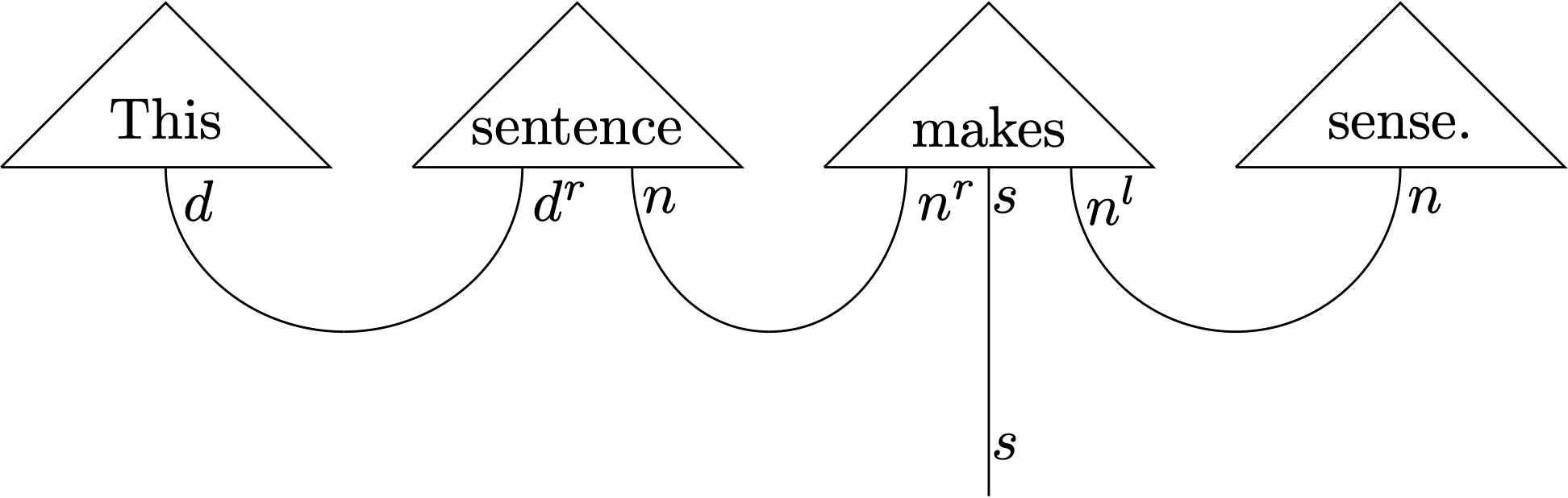

Surprisingly, there was almost a whole session on Day 5 dedicated to categorical linguistics. So apparently linguistics (or more exactly NLP) is an important subarea of ACT. In comparison to this importance, however, the presence of linguistics in ACT can hardly be called diversified or well balanced. As I have mentioned above, the predominant approach pursued in categorical linguistics is based on categorial grammar, especially Lambek’s theory. Its current version is pregroup grammar, which again crucially relies on monoidal categories. In fact, pregroup grammar is a subpart of the above-mentioned “quantum linguistics” project. Specifically, it takes care of the compositional aspects of natural language grammar, whereas quantum theory (by means of vectors, Hilbert spaces, etc.) takes care of its noncompositional aspects. The following example is adapted from de Felice et al.’s talk entitled “Functional language game for question answering” (based on this paper), which, despite its name, contains a pretty accessible introduction to categorical NLP.

(I used the following DisCoPy code plus some LaTeXiT fine-tuning to generate the above diagram.)

from discopy import Ty, Box, Id, Cup, pregroup, Word

# define basic types

d, n, s = Ty('d'), Ty('n'), Ty('s')

# assign types to words

this, sense = Word('This', d), Word('sense', n)

sentence = Word('sentence', d.r @ n)

makes = Word('makes', n.r @ s @ n.l)

# compute the type of the whole sentence

whole = this @ sentence @ makes @ sense >> Cup(d, d.r) @ Cup(n, n.r) @ Id(s) @ Cup(n.l, n)

# draw diagram and convert it to TikZ code

pregroup.draw(whole, path='act2020-5-4', to_tikz=1)

As is shown in the above diagram, pregroup grammar analyzes natural language sentences by type-based (or “typelogical” à la Moortgat) computation. Each word is assigned a type, either simple (e.g., This::d) or complex (e.g., sentence::d^r n), and a sentence is “asserted” as grammatical if the computation (mainly function application) leads to a simple type s. Importantly, pregroup grammar doesn’t specify what each word really means for an ordinary speaker, so it cannot distinguish, say, sense and nonsense, as both are of type n. To handle lexical meanings computational linguists still largely rely on vector space–based (aka distributional) semantics. The merit of categorical NLP is that it nicely marries the two approaches, because vector spaces can obviously be given category-theoretic interpretations too.

This half-distributional-half-compositional theory looks promising in the realm of NLP, even though (IMHO) the linguistics theory it is based on is far from being the mainstream in linguistics-linguistics, where the predominant research paradigm is still based on Chomsky’s theory, as least as far as syntax (or “grammar” in a narrow sense) is concerned. As a pupil of both (pure) linguistics and category theory, I am not biased towards or against either tradition. However, it is also my wish to see more theoretical paradigms of modern linguistics than merely categorial grammar being given category-theoretic interpretation, because I do believe that category theory has the potential to become a “universal language” to help us reason about all sorts of things and that the various competing theories about natural language grammar—be it transformational-generative grammar or categorial grammar or construction grammar or whatever—all have something valuable that others can learn from.

Anyway, thanks to the ACT conference I paid more attention to pregroup grammar and also learned something about the cutting-edge techniques in NLP. I will leave the details of pregroup grammar to a future blogpost, hopefully as part of my Category Theory notes II series. Needless to say, I still have many doubts about the theory as an adequate explanation of human language grammar (partly because I am trained in the Chomskyan school), but that doesn’t prevent me from wanting to learn more about how it works. Hopefully my curiosity won’t kill any $\mathbb{cat}$!😹

Summary

In sum, I learned a lot more from the ACT2020 conference than I had expected. Even though my background knowledge of category theory on the one hand and of the relevant subjects on the other hand is far from enough, I have managed to grasp the main methods (e.g., how a particular subject could be given a category-theoretic interpretation) as well as gain numerous new insights throughout the week, which has in turn greatly broadened my horizons. For instance, if it were not for the conference, I probably wouldn’t even have the slightest interest in finding out what a Petri net or a lens was, nor would I have the intention to read on quantum theory or game theory. Now that I’m no longer a graduate student, I must begin to face the cruelty of the adult world on my own, but I hope my motivation to learn new stuff won’t wear off and that I will keep wanting to bring the linguist-linguist’s perspective into categorical linguistics.🍀

This is the end of my posts about ACT2020. Thanks for bearing with me!

Leave a comment