Quick links:

Tutorial Day notes:

- Lecture 1: Introduction to applied category theory (David Spivak, video)

- Lecture 2: An introduction to string diagrams (Fabrizio Genovese, video)

- Lecture 3: The Yoneda lemma in the category of matrices (Emily Riehl, video)

- Lecture 4: Monads and comonads (Paolo Perrone, video)

In this fourth and final lecture of the Tutorial Day entitled “Monads and comonads,” Paolo Perrone taught us the basics of (co)monads with clearly presented examples. In the beginning, Paolo gave the one-line general remark that “monads are particular functors with extra structures.” Then he gave out the formal definition below:

Let $\mathcal{C}$ be a category. A monad $(T,\mu,\eta)$ on $\mathcal{C}$ involves:

1) a functor $T:\mathcal{C}\rightarrow\mathcal{C}$,

2) a natural transformation $\eta: 1_\mathcal{C}\Rightarrow T$ called “unit” ($\eta$ stands for “Einheit” in German), which is $C \rightarrow TC$ for $C\in\mathcal{C}$ in terms of components, and

3) a natural transformation $\mu: TT\Rightarrow T$ called “multiplication,” which is $TTC\rightarrow TC$ in terms of components,

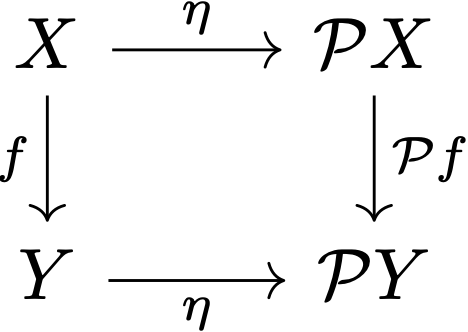

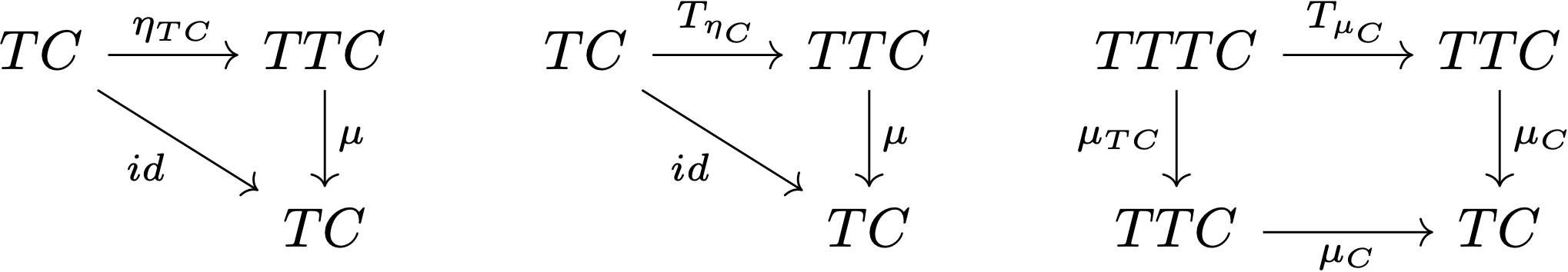

such that for all $C\in\mathcal{C}$ the following three diagrams commute:

Together with the formal definition he also gave us an informal characterization of the “monad idea”:

The idea behind monad is a way to “extend” our spaces to allow for extra outcomes, which might be more general elements or functions with more general output. (PP)

Then, Paolo went on to present examples of monads. The first example was that of power sets, which involved a monad in the category $\mathbf{Set}$. Specifically, given the power set functor $\mathcal{P}: \mathbf{Set}\rightarrow\mathbf{Set}$, the unit $\eta$ of the monad maps a set $X$ to its power set by sending each element $x\in X$ to the singleton set ${x}\in\mathcal{P}X$, and the multiplication $\mu$ of the monad sends sets of subsets of $X$ to subsets of $X$ by taking their union. Paolo explained how the monad idea was reflected in this example as follows:

$\mathcal{P}X$ extends $X$ in the sense that it is as if we can embed $X$ in $\mathcal{P}X$. We want to extend our original set because, for example, in a computer program the outcome might not be uniquely determined but could merely be a subset. (PP)

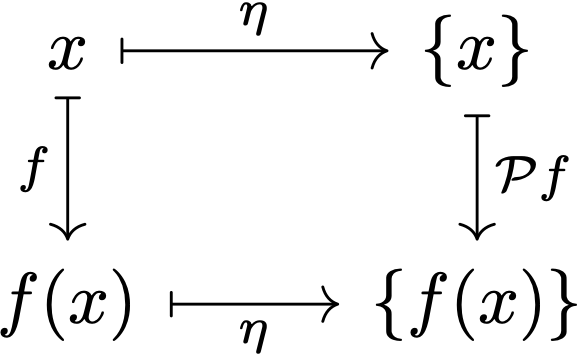

To illustrate, given a $\mathbf{Set}$-morphism $f: X\rightarrow Y$, the naturality square for $\eta$ is (here Paolo omitted the subscripts $X$ and $Y$ in the $\eta$-component labels but that doesn’t hinder understanding)

which commutes because for any $x\in X$ we have (again the component label subscripts are omitted here)

After the power set example, Paolo taught us what a Kleisli category was. According to Wikipedia, a Kleisli category is “a category naturally associated to any monad.” So, as Paolo explained to us, given a monad $(T, \mu, \eta)$ on $\mathcal{C}$, the objects of the Kleisli category based on this monad are just objects of $\mathcal{C}$, while the morphisms of the Kleisli category (aka “Kleisli morphisms”) are defined as follows:

$X\rightarrow Y$ is a morphism in the Kleisli category where $X\rightarrow TY$ is a morphism in $\mathcal{C}$.

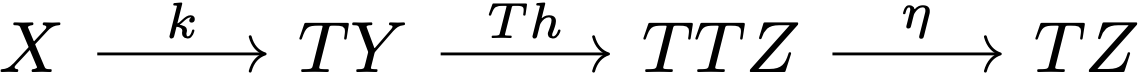

An identity morphism $X\rightarrow X$ in the Kleisli category is defined by the $\mathcal{C}$-morphism $\eta: T\rightarrow TX$. And composition in the Kleisli category is defined as follows:

For $k: X\rightarrow Y$ and $h: Y\rightarrow Z$ in the Kleisli category, namely $X\rightarrow TY$ and $Y\rightarrow TZ$ in $\mathcal{C}$, $h\circ k: X\rightarrow Z$ is defined by the $\mathcal{C}$-composition

(Edit: The $\eta$ from $TTZ$ to $TZ$ in the above diagram should be a $\mu$ instead.)

According to Paolo, Kleisli categories are useful because they define functions with generalized output and allow for extra effects like null or multiple results. In the example of power sets, for instance, the Kleisli morphisms are just set-theoretic relations (which are sort of like “generalized functions”).

The next example Paolo gave was the action/writer monad.

Mathematicians like calling it the action monad, while computer scientists prefer the name writer monad. (PP)

The definition of this monad is based on a monoid, such as the set of real numbers under addition or the set of strings generated by a set $X$ under concatenation. This monad maps $X$ to a product $X\times M$, where $M$ is an extra thing being added to the “pure outcome.” And the Kleisli morphisms related to this monad are something like $X\rightarrow Y\times M$, which sends $x\in X$ to pairs $(y,m)$ in $Y\times M$. That is, it gives output $y$ for input $x$ and does something else about $y$ such as writing it to the screen or a log file.

After introducing the concept of monad, Paolo continued to introduce comonad. The definition of a comonad is basically the same as that of a monad, except that the arrows in (2) and (3) as well as the three commutative squares are all reversed. Paolo also gave us a “comonad idea”:

The idea behind a comonad is a way of expanding spaces to encode extra information. (PP)

He then gave us the definition of a co-Kleisli category. A co-Kleisli morphism $X\rightarrow Y$ for the comonad $C$ is a morphism $CX\rightarrow Y$, which is a “function” that depends on extra data and has access to extra information.

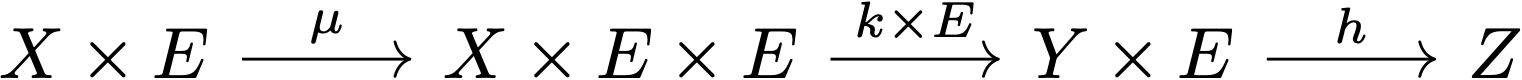

Paolo exemplified this with the reader comonad (of $\mathbf{Set}$). Let $E$ be a fixed set (e.g., of extra data). Then, given any other set $X$, the “counit” of the comonad maps $X\times E$ to $X$ (i.e., it puts extra data in $X$), and the “comultiplication” of the comonad maps $X\times E$ to $X\times E\times E$ (i.e., it copies the extra information). Accordingly, the co-Kleisli morphisms related to the comonad are of the pattern $k: X\times E\rightarrow Y$, which basically means that in order to produce the output we have to also look at the extra information (e.g., some database). Composition in this co-Kleisli category is defined as follows:

For $k:X\times E\rightarrow Y$ and $h: Y\times E\rightarrow Z$, define $X\times E\rightarrow Z$ by the following composition:

Finally, Paolo gave another example of comonad from computer science: the string comonad. First take a monoid $(\mathbb{N},+,0)$. Then take a set $X$ and form a set of sequences from it. The string comonad maps $X$ to $X^\mathbb{N} =$ {$(x_0, x_1, \dots): x_i\in X$}; namely, it keeps the trajectory or history of the string operation (i.e., we can intuitively think of the superscript $\mathbb{N}$ as some sort of computational history). Under this setting, the counit $X^\mathbb{N}\rightarrow X$ of the comonad can be thought of as forgetting the history, and the comultiplication $X^\mathbb{N}\rightarrow (X^\mathbb{N})^\mathbb{N}$ of the comonad can be thought of as looking at the history of the history. Accordingly, the co-Kleisli morphisms related to the string comonad have access to the computational history—they are “maps with memory” in Paolo’s words.

References mentioned in this lecture:

- Paolo Perrone: Notes on category theory with examples from basic mathematics, Chapter 5

- Emily Rihel: Category Theory in Context, Chapter 5

- Bartosz Milewski: Category Theory for Programmers + blog

This is the end of my notes from the Tutorial Day.

Leave a comment