Quick links:

Tutorial Day notes:

- Lecture 1: Introduction to applied category theory (David Spivak, video)

- Lecture 2: An introduction to string diagrams (Fabrizio Genovese, video)

- Lecture 3: The Yoneda lemma in the category of matrices (Emily Riehl, video)

- Lecture 4: Monads and comonads (Paolo Perrone, video)

In this second lecture by Fabrizio Genovese entitled “An introduction to string diagrams,” we were taught the basics of string diagrams and especially their uses in monoidal categories. Frankly speaking, this topic isn’t elementary at all, as most introductory textbooks on category theory that target nonmathematicians don’t even mention it. But I’m also aware that it is really popular among applied category theorists (see Fong & Spivak’s textbook for an impression). I haven’t asked around why that is the case (let me know if you happen to know 🙂) but there ought to be some close connection between monoidal categories and real-world situations (this blog post might be relevant).

Anyway, the lecture was easy enough to follow even for students with no prior knowledge of monoidal categories. Fabrizio pointed out right at the beginning that string diagrams represented a sort of graphical reasoning, which as a general idea and practice dates back to ancient history (though it kind of fell out of fashion for a while). Then he gave the following one-line summary of the subject—before turning the camera to a piece of paper and beginning to hand-draw string diagrams.

String diagrams are like a jungle. There are multiple flavors of them. (FG)

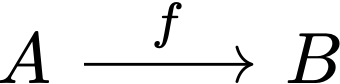

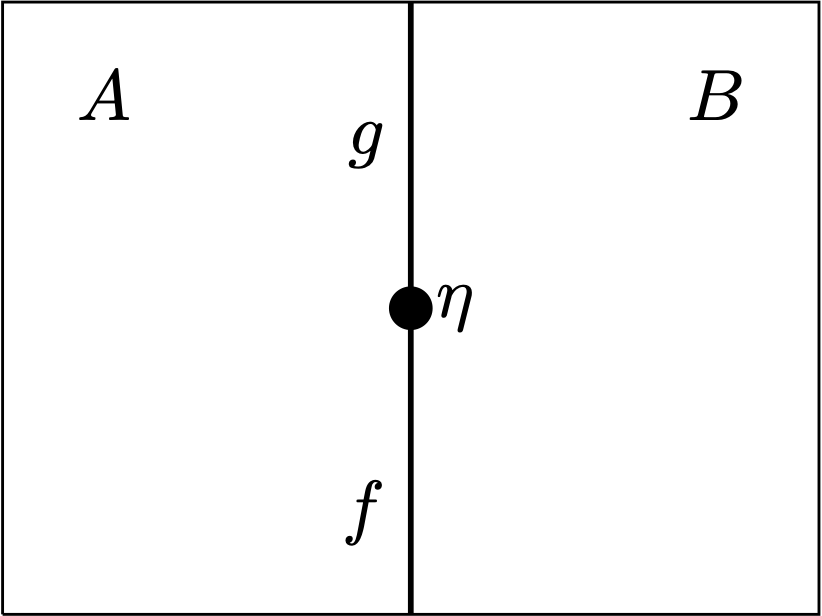

String diagrams differ from the ordinary diagrams typically seen in introductory category theory textbooks in that the graphical symbols for objects and morphisms are sort of swapped. While objects are “zero-dimensional” dots or points (of course these are not really zero-dimensional as we see them drawn on paper but let’s pretend they are) and morphisms are one-dimensional lines in ordinary diagrams, they become (respectively) lines and points in string diagrams. For example:

becomes

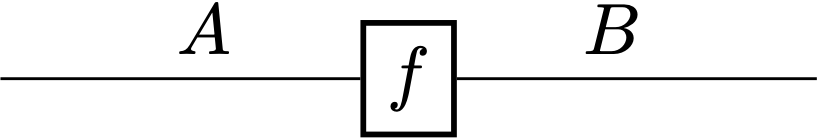

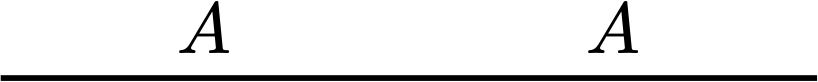

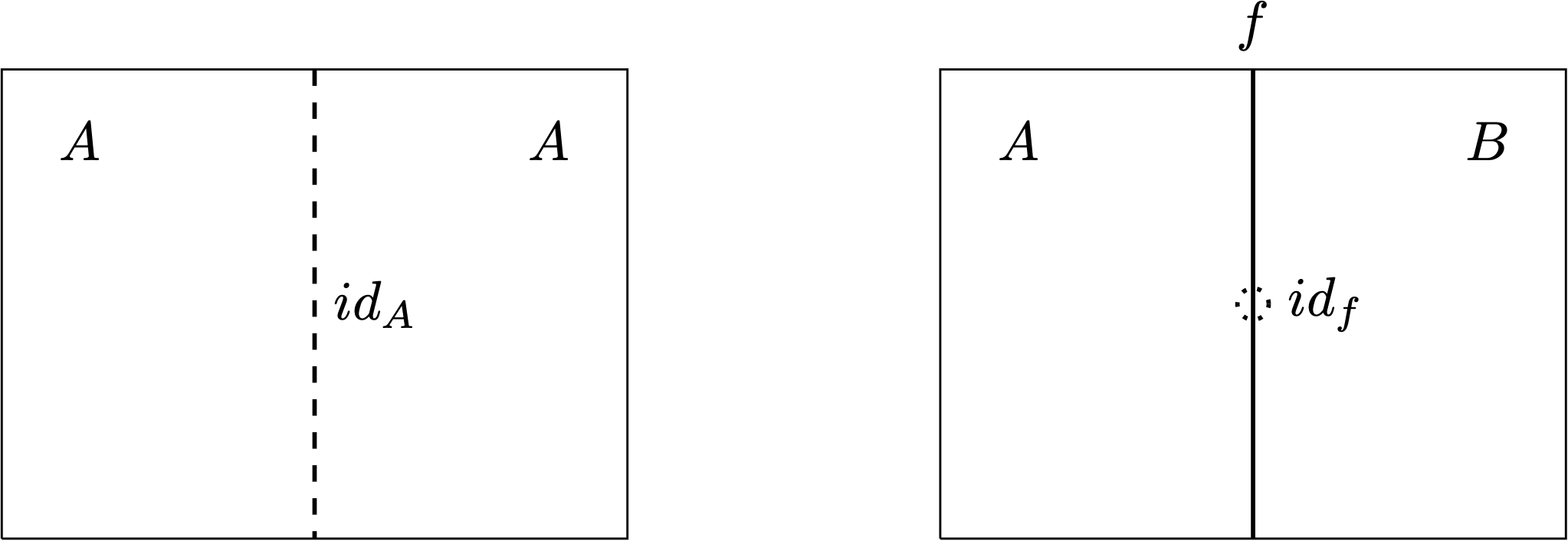

This is essentially a switch of perspective, and we can define syntactic sugars with it. For instance, identity morphisms, which do nothing, can just be omitted in string diagrams—or conceived as invisible, implicit boxes. So the first half of

becomes

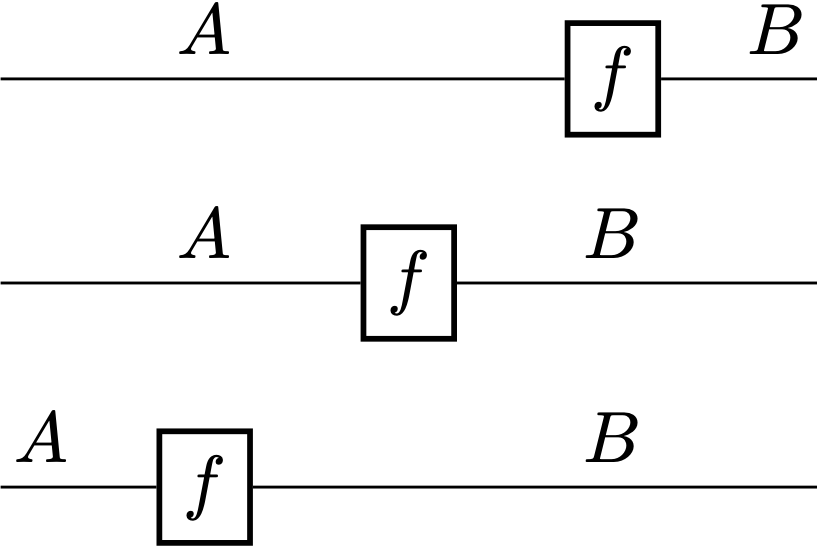

Fabrizio emphasized that it didn’t matter where to put the boxes in string diagrams as long as connectivity was preserved. So the following three string diagrams are all the same:

The only thing that matters is what is connected to what. (FG)

Fabrizio also pointed out that different people might prefer reading and drawing string diagrams in different directions:

- the canonical direction in category theory and categorical physics is from bottom up;

- the conventional direction in categorical linguistics is from top down;

- the way Fabrizio draws them in this lecture is from left to right.

Currently the only way no one draws string diagrams in is from right to left… (FG)

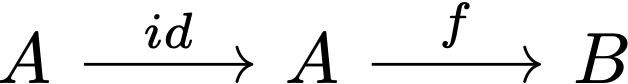

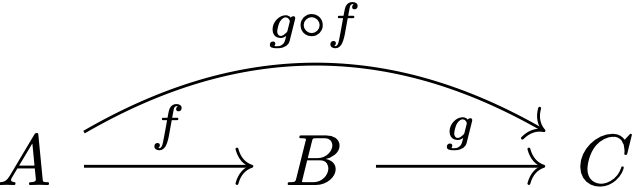

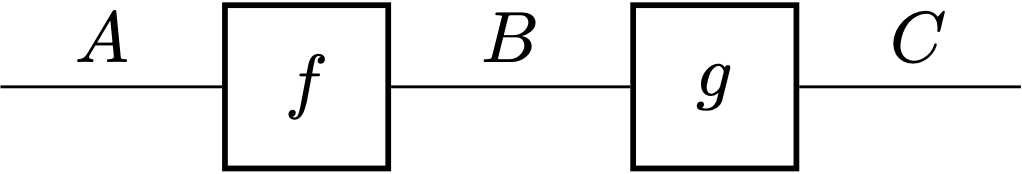

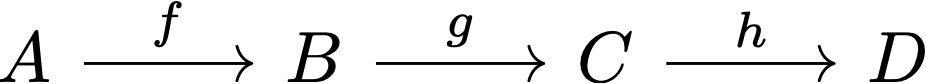

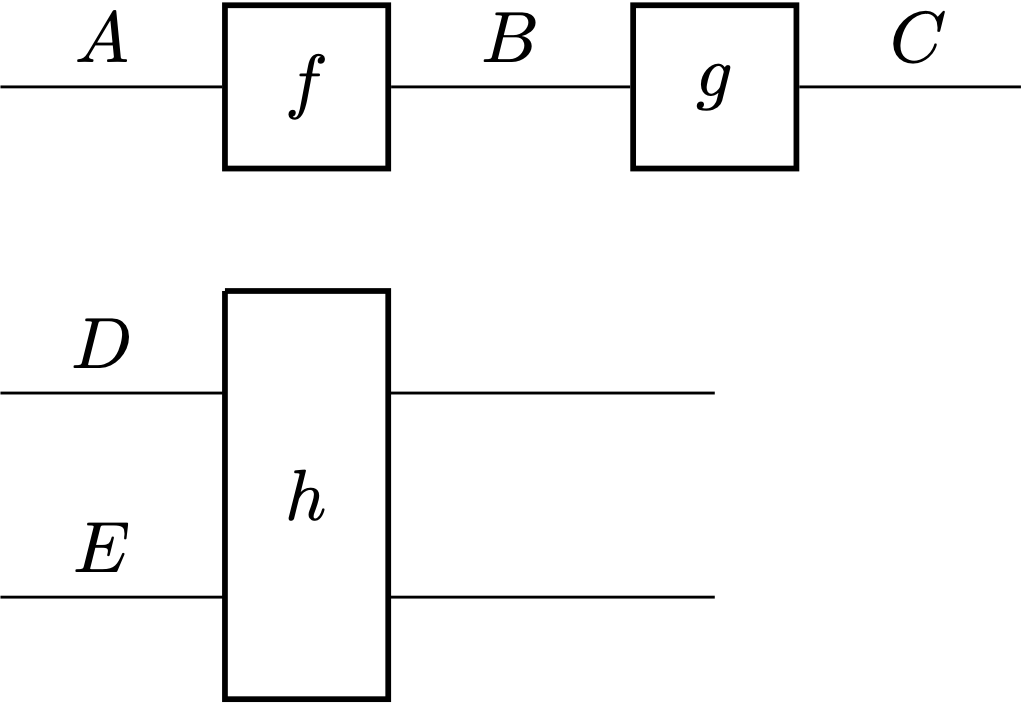

Next, Fabrizio went on to introduce how composition was done in string diagrams. For example, the normally presented composition

where the long arrow $f\circ g: A\rightarrow C$ is the composite of the two short arrows $f: A\rightarrow B$ and $g: B\rightarrow C$, becomes

which, in Fabrizio’s words, gives a nice process-oriented presentation of composition—e.g., $f$ takes $A$ as input and yields $B$ as output, which $g$ subsequently takes as input—just like the input/output on circuit boards. At this point Fabrizio once again reminded us that what mattered was the connectivity rather than the particular shapes of the strings/wires, with the following real-life metaphor:

When you connect your toaster to the socket it doesn’t matter whether you bend the wire; all that matters is that the wire is connected. (FG)

After illustrating how string diagrams work in basic categories, Fabrizio entered the main section of his lecture; namely, the application of string diagrams in higher categories, in particular 2-categories. Simply put, 2-categories are categories that have morphisms between morphisms, which are called “2-cells” or “2-morphisms.” And the string-diagram solution to their representation is an intuitive extension of that of 1-categories:

- draw objects as two-dimensional surfaces,

- draw morphisms as one-dimensional lines serving as boundaries of adjacent surfaces, and

- draw 2-morphisms as zero-dimensional dots on the surface boundary lines.

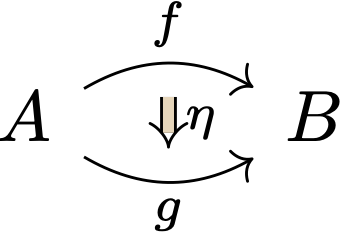

In particular, step 3 suggests that each surface boundary line may accommodate multiple morphisms, and the order to read them is from bottom up. For example, the following normally drawn 2-category (which looks exactly like a 1-category with a natural transformation)

becomes

which looks very different!

Just like identity morphisms in 1-categories, identity morphisms in 2-categories are left out in string diagrams—or we could conceive them as invisible boundaries/dots.

And composition in 2-categories is also pretty straightforward.

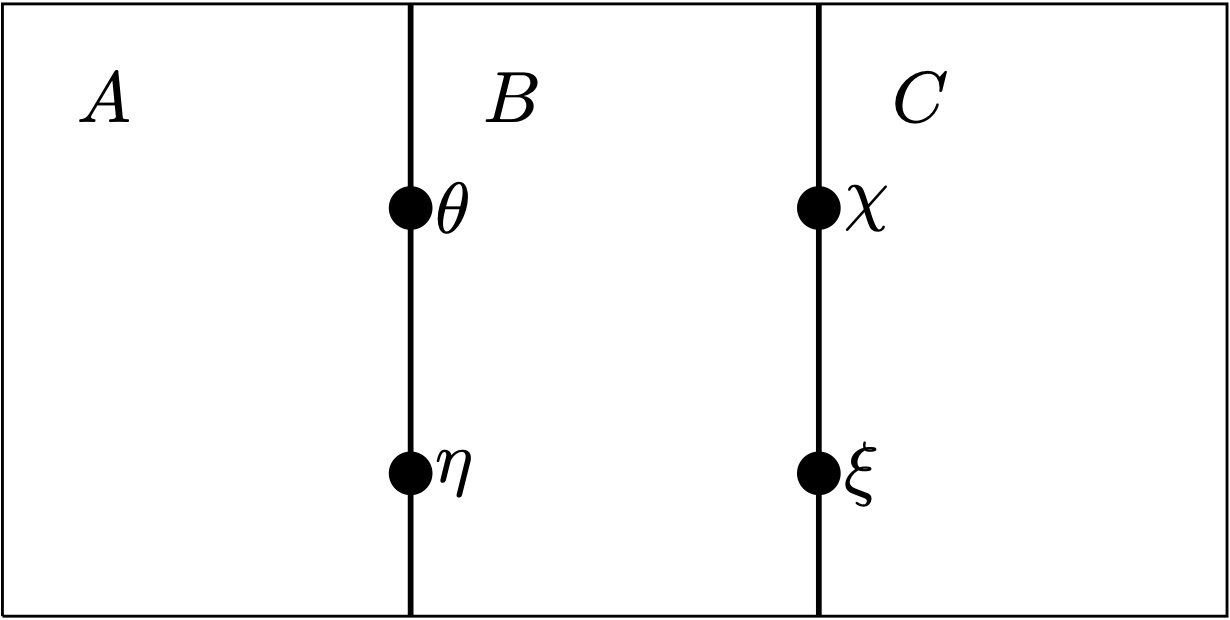

Moreover, 2-morphisms can be composed either vertically or horizontally. For example, in the following string diagram

the four 2-morphisms can be composed either first vertically and then horizontally (i.e., $(\xi\cdot\chi)\circ(\eta\cdot\theta)$) or first horizontally and then vertically (i.e., $(\xi\circ\eta)\cdot(\chi\circ\theta)$). The result would be the same (as in natural transformation composition in 1-categories; I have a previous blog post about this).

After giving out the above examples, Fabrizio mentioned that we could further lift the categorical dimension and talk about $n$-categories, which have morphisms between morphisms between … between morphisms (up to $n$). And string diagrams can also conveniently handle those higher categories, though when $n\ge 4$ things become hard to visualize. In 3-categories, though, an object in string diagram would be a space, a 1-morphism would be a boundary surface between adjacent spaces, a 2-morphism would be an edge line on one of the boundary surfaces, and a 3-morphism would be a dot on a boundary surface edge line.

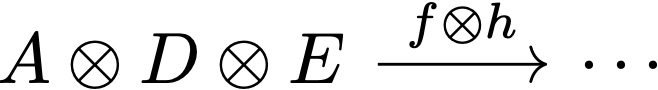

The most important kind of categories out there for string diagrams to represent are the monoidal categories. Fabrizio characterized a monoidal category as a 2-category with one object—more exactly a “pseudomonoid in the cartesian monoidal 2-category $\mathbf{Cat}$” according to nLab (not that I understand what this means 😅), and the usual formal definition is “a category equipped with a monoidal structure” according to Wikipedia (this is more accessible to me). In such a category we can perform parallel composition (via the “tensor product” operation $\otimes$) in addition to normal composition (this presentation might be helpful for the uninitiated). And since a monoidal category has only one object, there’s no need to explicitly draw out any (delimited) surface. For example, in the following string diagram

apart from the normal composition $g\circ f$ we also have the parallel composition (in non-string-diagram format)

As Paolo Perrone explained in the conference Zoom chat after I asked, the tensor product symbol $\otimes$ highlights that this is not necessarily categorical product and also generalizes the tensor product of vector spaces (I’m not familiar with the latter point but the former reason is good enough for me). Two other audience members also mentioned something about tensor categories:

- A tensor category is often used to mean a monoidal category with some particular extra structures. (Joe Moeller)

- A tensor category is usually assumed to be symmetric monoidal. (Andrei Konovalov)

In the last part of the lecture, Fabrizio introduced a few new string-diagrammatic operations, such as “knots,” “traces,” and “snakes.” I’m not going to give examples here because I don’t fully understand their application scenarios (e.g., in quantum mechanics), but I guess the pedagogical point here was the following:

When you come up with a new flavor of category, there may or may not be a string diagram for it. The only way to find out is to make up a graphical calculus for it by yourself. (FG)

References mentioned in the lecture:

- André Joyal & Ross Street: The geometry of tensor calculus

- Graphical Linear Algebra

- Peter Selinger: A survey of graphical languages for monoidal categories

- Daniel Marsden: Category theory using string diagrams

Leave a comment