In the previous post, I introduced my submission to the 2022 Applied Category Theory conference (ACT2022). Now that the conference is over, I’d like to share some notes on the other linguistic stuff at the conference. Apart from my own poster, there were five other presentations touching on linguistics, all given by category theory experts from STEM backgrounds. In this post, I comment on four of them (excluding a software demo) from a linguist’s perspective. Since these are just personal notes, my narrative doesn’t necessarily reflect that of the original authors, because I’m more interested in general ideas and interdisciplinary connections. For particular details of particular talks, just follow the quick links below.

Coecke et al. & DisCoCirc

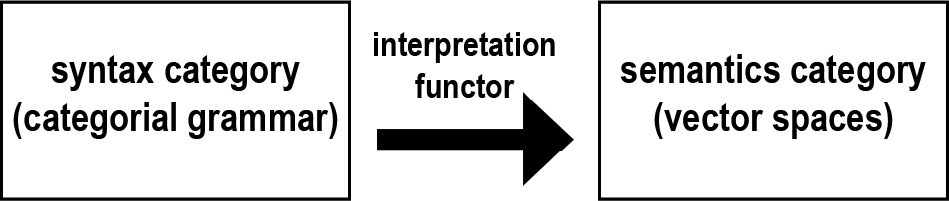

Bob Coecke’s group gave three talks in a row, all about their NLP-oriented model of natural languages named DisCoCat (=Distributional-Compositional-Categorical)—in particular about its most recent iteration, DisCoCirc (=Distributional-Compositional-Circuit). As the names suggest, these models integrate distributional (i.e., vector space–based) and compositional (i.e., logically based) approaches to natural language semantics (for NLP purposes). Unsatisfied with the statistics-only method dominating the field and the neural network black boxes, Coecke’s group has endeavored to reintroduce linguistic rules and logical methods to the game in the past decade via a categorification of distributional semantics—into a semantics category of vector spaces—and a functor connecting it with a category for natural language syntax, canonically based on Lambek’s pregroup grammar, which is a particular development of categorial grammar.

Figure 1. The basic mechanism of DisCoCat

Figure 1. The basic mechanism of DisCoCat

Coecke et al.’s preference for pregroup grammar as the syntactic calculus is mainly due to its high compatibility with the vector space–based semantic model, as both sides in the above figure have a “compact closed” structure, which in turn enables the functorial connection.

Since pregroup grammar is mainly about how words logically compose into sentences, DisCoCat’s main linguistic focus is at the single-sentence level. However, that is clearly not enough for practical purposes, since real-life data are never isolated sentences. Against this background, DisCoCirc is an extension of DisCoCat to the text level—via additional mathematical tools like Frobenius algebra. It supports the composition of individual sentences into sentence groups and therefore can handle discourse phenomena like noncommutative text flow (1a) and text-dependent referent assignment (1b) in a category-theoretic way.

(1) a. Add egg yolk and salt. Whisk mix for 20 seconds. Add mustard and acid. Whisk mix for 30 seconds. Slowly add oil while whisking.

b. Alice is a dog. Bob is a person. Alice bites Bob.

(Coecke 2021:196–197)

In (1a), the correct interpretation of the sentences crucially depends on their ordering, so the composition of these sentences is not simply a matter of conjunction. In (1b), an adequate interpretation of the third sentence hinges on the information in the first and the second sentence, which help us assign correct referents to “Alice” and “Bob.”

Key references (o = official version, a = arXiv version):

[1] DisCoCat: Coecke, B., M. Sadrzadeh & S. Clark (2010). Mathematical foundations for a compositional distributional model of meaning. Linguistic Analysis 36, 345–384. (o, a)

[2] DisCoCirc: Coecke, B. (2021). The mathematics of text structure. In Casadio, C. & P. J. Scott (eds.), Joachim Lambek: The interplay of mathematics, logic, and linguistics, 181–217. Cham: Springer. (o, a)

Linguists may feel surprised that the above should be considered a new direction in the 2020s, since the relevant phenomena have long been studied in linguistics (e.g., in dynamic semantics, since the 1980s). However, we must not forget the gigantic gap between modern-day theoretical linguistics and NLP. Given the increasing difficulty of communication between NLP practitioners and linguists, I actually think Coecke et al.’s categorical approach could potentially serve as a bridge between linguistics and NLP—especially if its mathematical methods could be made less dependent on the particular linguistic theory it currently relies on (i.e., categorial grammar).

The last paragraph reminds me of something that I have only recently realized. That is, despite Lambek’s (1988) differentiation of the two terms “categorial” and “categorical” (see an earlier post of mine), the general perception nowadays is still that categorical linguistics is basically a category-theoretic lifting of categorial grammar. My opinion is strongly different (which I have repeatedly mentioned on this blog), not only because my own categorical linguistic work has nothing to do with categorial grammar, but also because I don’t think such a tight association is doing justice to category theory itself, which is supposed to be a general theory of structure and compositionality.

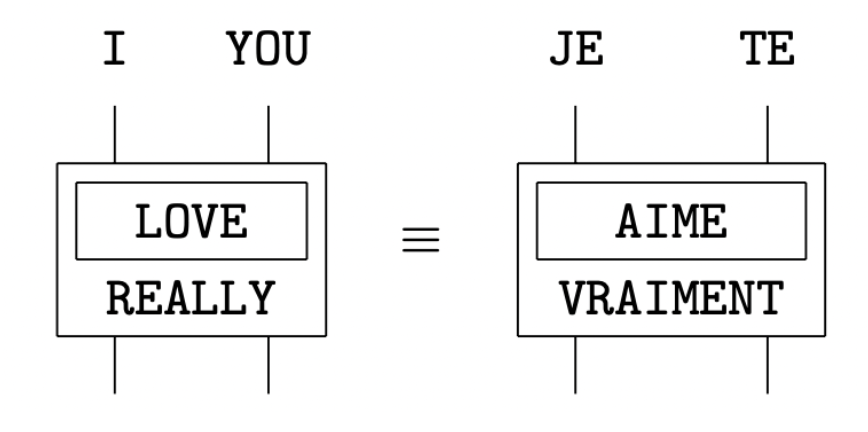

In fact, I’ve noticed some recent signs of deviation from the categorial grammar canons in Coeckian works, which I personally find refreshing. For instance, in Coecke’s ACT2022 presentations, word order is finally acknowledged (at least to some extent) to be nonessential for semantic interpretation. Thus, both English I really love you and its French counterpart Je t’aime vraiment are represented by the same circuit-shaped diagram below:

Figure 2. Example DisCoCirc diagrams (Coecke 2022, “Talking space”)

Figure 2. Example DisCoCirc diagrams (Coecke 2022, “Talking space”)

Again, 21st-century linguists like myself might be surprised at the “obsession” of categorial grammarians with word order rules—not that it’s a bad thing, of course—because a most fundamental result in current theoretical linguistics, at least in generative linguistics, is the “interface” nature of word order. That is, human language syntax is “blind” (Chomsky’ term) to linear order and only about hierarchical structure (roughly, what word group contains what word groups as members), while the syntactic structure only gets linearized via some mapping algorithm when it is “externalized” to the phonological module. And even there, the linear order nature of language is merely a byproduct of the oral-auditory modality. If the same syntactic structure is externalized via the manual-visual modality, as in sign languages, then the strict linearity requirement vanishes and a lot of things can be expressed simultaneously.

As such, seeing the dwindling effect of word order rules in the DisCoCirc model was a big FINALLY moment for me. By the way, I’ve noticed a similar “dissatisfaction” in a recent master’s thesis written by one of Coecke’s students:

[The DisCoCat diagram for the sentence “Alice deeply likes Bob”] seems somewhat unnatural at a theoretical level—why should the “deeply” comb only modify Alice’s noun wire? …[W]e probably should not faithfully follow pre-established categorial grammar when designing our theory of language circuits and circuit components. // The fact that the last input of “likes” remains free here, is an artefact of the fact that categorial grammars were designed to act as a bookkeeping system for linear word order. (Jonathon Liu’s 2021 Oxford University MSc thesis “Language as circuits” p.73)

Liu went with dependency grammar as the linguistic foundation for his version of DisCoCirc. This in my book is an awesome move, because it directly shows that Coeckian categorical linguistics may well “survive” in a different linguistic universe.

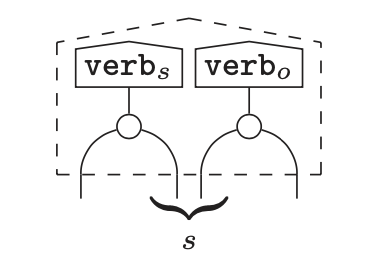

While preparing these notes, I’ve noticed some further recent features of DisCoCat that are getting close to how things are done in linguistics. Take the “internal wiring” approach to “compact verbs” introduced in Coecke, Lewis & Marsden (2018) for instance (which is further developed in Coecke’s 2021 chapter mentioned above). It treats a transitive verb like paint (as in he painted the table red) as an amalgam of a subject-oriented part $\mathrm{verb}_s$ and an object-oriented part $\mathrm{verb}_o$ as in the following string diagram.

Figure 3. The internal wiring of compact verbs in DisCoCat (Coecke 2021:191)

Figure 3. The internal wiring of compact verbs in DisCoCat (Coecke 2021:191)

This is somewhat similar to the lexical decompositional approach to verbal event structure that has been systematically pursued in linguistics since as early as the 1960s (originally in the guise of “generative semantics”). From a linguist’s perspective, what Coecke et al. are doing is representing the causative-resultative event structure of paint in their string diagram language. On that note, my own ACT2022 submission is also about a lexical decompositional theory in linguistics (root syntax). 😊

GLP & fibrational linguistics

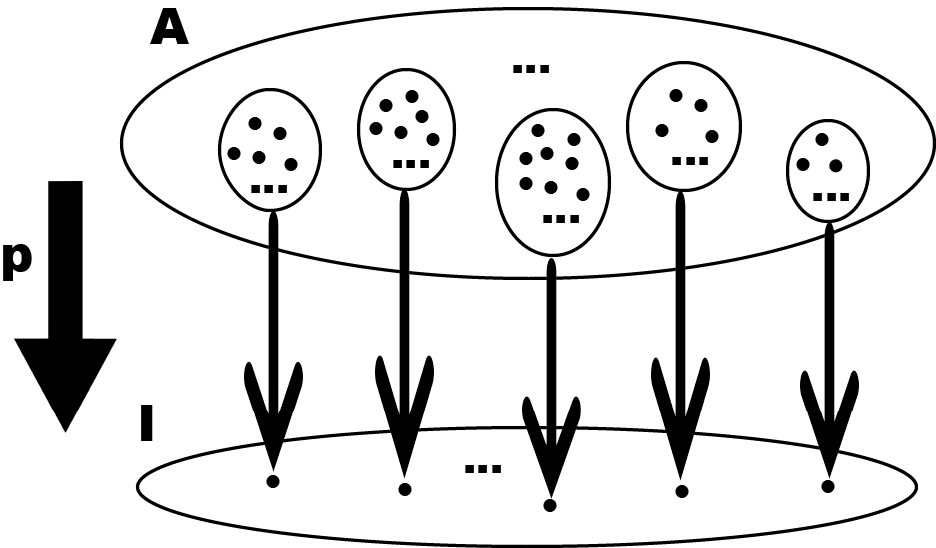

After recording my thoughts on Coecke et al.’s work, next I turn to Genovese, Loregian & Puca’s ACT2022 presentation on what they designate “fibrational linguistics,” which is a category-theoretic modeling of vocabulary acquisition. Fibration is a quite specific concept from algebraic topology, which few linguists are familiar with. But the authors’ supplemental paper “Fibrational linguistics (FibLang): First concepts” provides a slightly gentler introduction. In very loose terms, a fibration can be likened to a special surjective map, such as $p: A \rightarrow I$ in the figure below, where each element in the target set $I$ corresponds to a subset of elements (called a “fiber” or “bundle”) in the source set $A$.

Figure 4. A very loose depiction of a fibration

Figure 4. A very loose depiction of a fibration

Of course, there’s a lot more conditions in the actual definition of fibration, which also constitute much of the mathematical complexity in GLP’s work—to begin with, both the source and the target sets in the above loose delineation are to be replaced by categories. Nevertheless, I personally find the brute simplification above a lot friendlier to working linguists, who usually know nothing about topology but are pretty familiar with basic set theory.

GLP’s core linguistic idea is actually a simple and straightforward one. In a category-theoretic version of Figure 4, where $p$ is a real fibration, we can take $I$ (which they call $\mathcal{L}$) to be a collection of words—or more exactly lexical items—and take $A$ (which they call $\mathcal{E}$) to be an organized or post-fibration space of meanings. Then, each fiber $\mathcal{E}_L$ is collectively taken to be the meaning or definition of a lexical item $L\in\mathcal{L}$. For instance, the fiber $\mathcal{E}_\mathrm{dog}$ for the word dog might contain descriptions like “canine,” “four-legged,” “bark,” “human’s best friend,” etc. Under this setting, to aquire a lexical item is to fill its initially empty fiber with appropriate descriptions. To further complete the story, GLP also define a pre-fibration meaning space, in the form of a category $\mathcal{D}$, which is like an unorganized black box of linguistic meanings in a speaker’s head, and only via some “organizing” map $s$ do we get the well-fibered meaning category $\mathcal{E}$:

\[\mathcal{D}^p \overset{s}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{E}^p \overset{p^\#}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{L}\]Here, the original fibration map $p$ is replaced by $p^\#$ (the # superscript is used to explicitly mark a map as a fibration). Interestingly, GLP conceive a $p$-induced composite map like the above as just a speaker. Moreover, they assume that each speaker has their own mental space of meanings. This is actually a highly linguist-y way of thinking—it is the I-language (or more exactly idiolect) view in Chomskyan terminology. Apropos, the authors begin their paper with a criticism of Chomsky (vis-à-vis Wittgenstein), but to be honest I find that unnecessary (and somewhat imprecise), because a lot of what’s being developed in the paper are actually fully compatible with Chomskyan linguistics.

At this point, I’d like to make some further linguistic remarks on GLP’s idea. The objects in $\mathcal{L}$ are more exactly phonological exponents (or “signifiers” à la Saussure), while the fibration defines what linguists call “sound-meaning pairs” (or Saussurean “signs”). NB sound-meaning pairs needn’t be exclusively word-sized. The smallest sound-meaning pair in any language is called a morpheme, while each complete sentence is also a sound-meaning pair. In fact, a grammar is just a set of rules describing all and only the well-formed sound-meaning pairs of a language. As such, the categories $\mathcal{L}$ and $\mathcal{E}$ needn’t be conceived as (respectively) a bag of words and a bag of meaning descriptions. They can (and in fact certainly do) contain internal derivational structures as well. That is also GLP’s idea.

GLP emphasize three differences between their category-theoretic approach to natural languages and Coecke et al.’s approach. First, the functor in GLP’s work goes from semantics to syntax, while that in Coeckian categorial linguistics goes from syntax to semantics. Second, GLP remain agnostic about the specific internal structures of both the syntax and the semantics category, while Coecke et al. equip both categories with specific categorical structures. Third, the Coeckian syntax category only has derivational morphisms (i.e., type-logical reductions), while GLP’s syntax category can accommodate more kinds of morphisms, such as semantic connections between lexical items, which are ontological in nature from a general linguistic perspective.

I personally find all three features of GLP’s theory above awesome. The first feature is essentially about a new way to apply category theory to linguistics, and the second feature makes GLP’s theory compatible with multiple linguistic frameworks in principle. As I mentioned in the previous post, categorical linguistics as a field of research should not be confined to the categorial grammar approach on the one hand and should not be confined to just syntax/semantics (aka derivational/compositional issues) on the other hand. GLP’s work is a nice demonstration of both points. Finally, the third feature of their theory is essentially about the ontological vs. derivational distinction in linguistics, which I had also highlighted in my ACT2020 submission (my 2019–2020 categorical linguistic work was focused on ontological issues too).

Now let’s return to GLP’s particular presentation at ACT2022, the subtitle of which is “language acquisition.” Under the above fibrational setting, vocabulary learning in first-language acquisition involves filling in empty fibers in $\mathcal{E}$ via interaction with a “teacher” (e.g., a parent). This process involves further complexities due to (i) concomitant changes to the speaker’s language category $\mathcal{L}$ in the process of vocabulary learning, and (ii) the specific manner of teacher-learner interaction, which could be direct exemplification or verbal paraphrasis à la GLP. However, in this blogpost I’ll abstract away from all these details (see the original papers [1] [2] if you are interested). In much simplified terms, therefore, vocabulary acquisition can be described as an update of a learner $q$’s meaning space $\mathcal{E}^q$ based on some new information provided by a teacher $p$:

\[(\mathcal{E}^q \overset{q^\#}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{L}) \overset{p\textrm{'s teaching}}{\Longrightarrow} (\mathcal{E}^\widetilde{q} \overset{\widetilde{q}^\#}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{L})\]where $\widetilde{q}^\#$ minimally differs from $q^\#$ in the particular meaning fiber updated by $p$’s teaching.

Of course, GLP’s original technicalities are much more complex. But as far as I’m concerned, much of that complexity is due to their background assumptions about language acquisition—so that’s actually linguistically induced complexity. Likewise, as I mentioned above, quite some technical complexity in Coecke et al.’s DisCoCat model arises from their background linguistic assumptions too. The core category-theoretic ideas in both lines of work, on the other hand, actually feel quite straightforward.

MLS & monoidal modalities

The last presentation at ACT2022 about linguistics was McPheat, Lang & Sadrzadeh’s talk titled “Making modalities (lax) monoidal,” which was about a desirable property (i.e., lax monoidality) of two modal operators (i.e., the bang operator $!$ for multiplexing and the nabla operator $\nabla$ for permuting) in a particular logical system for natural languages (i.e., “Lambek calculus with soft subexponentials” or SLLM for short). Well, strictly speaking my own poster was the de facto last linguistics-themed presentation, but since I’ve already written a dedicated post on it, I’ll leave it aside in this “potpourri” post. 😛

Compared to Coecke et al.’s and GLP’s work, which are more “global” in that they address big picture issues of entire fields, MLS’s work seems to be more “local” in that it addresses a particular problem in a particular version of syntactic calculus. Nevertheless, I find their abstract the easiest to follow as well as the most informative among all the linguistics-themed submissions (including my own). This may partly have to do with the fact that everyone attending the ACT conference has some background knowledge in formal logic (& every categorical linguist knows Lambek calculus), but on top of that, their writing (and presentation) style is pretty lucid too, which we can all learn from.

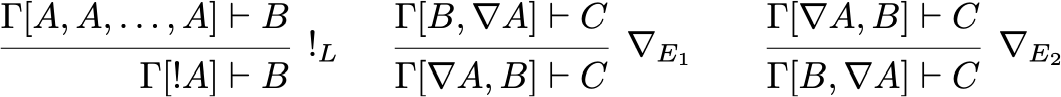

I have absolutely no idea as to why SLLM is abbreviated as such (apparently MLS don’t have a clue either XD), nor do I know what “soft subexponentials” are (I checked Kanovich et al.’s 2020 introductory paper but didn’t find answers). However, the basic mechanisms of the two modalities are clear enough: $!A$ makes multiple copies of $A$ and so makes it reusable, while $\nabla A$ makes it possible to swap the positions of $A$ and its neighbors. In more formal terms, these constitute the following rules:

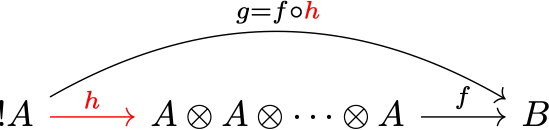

There are still more rules associated with the two modalities, but according to MLS the above three are the most important for their purpose. Also, these rules should be read from the bottom up in the ACT context. MLS didn’t specify why, but I guess that’s because once we start viewing SLLM as a category $\mathcal{C}(\mathrm{SLLM})$—which is moreover biclosed monoidal—the rules end up asserting the existence of certain “precomposable” morphisms, such as $h$ below (I omit the potential extra stuff in $\Gamma$ for expository convenience):

Figure 5. The $!L$ rule viewed categorically

Figure 5. The $!L$ rule viewed categorically

With logical formulas being viewed as $\mathcal{C}(\mathrm{SLLM})$-objects, and proofs, as morphisms, the $!L$ rule says that there is always a way to get from $\mathrm{hom}({A \otimes A \otimes \dots \otimes A}, B)$ to $\mathrm{hom}({!A}, B)$. This amounts to saying that given a morphism

\[f\colon {A \otimes A \otimes \dots \otimes A} \rightarrow B,\]it is always possible to cook up a morphism

\[g\colon !A \rightarrow B.\]An obvious way to do this is by precomposing $f$ with a morphism

\[h\colon !A \rightarrow {A \otimes A \otimes \dots \otimes A},\]whereby $g$ is just $f\circ h$. But this is just my own understanding.

As for their usage in linguistics, the two modal operators are mainly used in Lambekian categorial grammar to allow for the copying and movement of certain words, thus enabling categorial grammarians to derive anaphora and ellipsis phenomena like the following:

(2) a. John sleeps. He snores. (anaphora)

b. John plays guitar. Mary does too. (ellipsis)

c. John likes his code. Bill does too. (anaphora with ellipsis)

d. papers that John signed without reading (parasitic gap)

(example sources: [1] [2])

Abstracting away from technical details, MLS and colleagues basically derive these sentences by copying plus movement. Personally, I feel like these operations are making SLLM a little transformational-ish. Considering the incompatible basic assumptions of categorial grammar and transformational generative grammar, I don’t really know what that means. Nevertheless, I’m curious to see whether this “trend of deviation” will continue. 👀

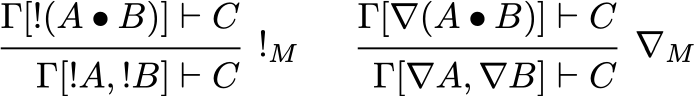

Back to category theory, despite the utility of the two modalities $!$ and $\nabla$, they as endofunctors on $\mathcal{C}(\mathrm{SLLM})$ do not preserve the monoidal structure of the category, which MLS deem undesirable for a number of reasons (see original papers for details). Therefore, they decided to make them lax monoidal—which is the weakest kind of monoidality on functors as well as the one suitable for SLLM—by manually adding more rules to SLLM. This is a legitimate move because, in McPheat’s words, the syntactic calculus is an artificial thing anyway. The specific rules they added were

Clearly, these are just the same pattern respectively applied to the two modalities. Categorically speaking, they give rise to two natural transformations (where $-$ and $=$ are random object placeholders):

\[m_\mathrm{!}\colon \mathrm{!}(-) \otimes \mathrm{!}(=) \rightarrow \mathrm{!}(-\, \otimes =)\] \[m_\nabla\colon \nabla(-) \otimes \nabla(=) \rightarrow \nabla(-\, \otimes =)\]These, together with the obvious unit morphisms $u_!\colon I \rightarrow !I$ and $u_\nabla\colon I \rightarrow \nabla I$, make $!$ and $\nabla$ qua endofunctors lax monoidal. In theory, one could also reverse the arrows in the natural transformations and the unit morphisms and make the endofunctors “oplax monoidal,” but MLS didn’t go with that option because it would make SLLM non-cut-eliminable.

As McPheat mentioned during the presentation, it is natural to want a functor between monoidal categories to preserve the monoidal structure. Considering the high popularity of monoidal categories in ACT, this suggests that monoidal functors should be pretty common. I don’t know whether that’s true, but monoidal functors happen to be relevant to my own work as well. My ACT2022 abstract has a section comparing my monadic approach to root-syntax semantics with a potential alternative approach based on applicative functors (a concept native to functional programming), and the latter are categorically strong lax monoidal functors.

Final remarks

Since the length of this post is already way over my usual standard, I’ll stop here. My overall impression after digesting the four talks is that they are all fantastic, and I’ve learned a lot from all of them. In addition, I have the feeling that category theorists studying natural languages are no longer exclusively following Lambek (whose framework is still the backbone of the linguistics corner of ACT, of course) but gradually taking some general linguistic ideas and methods into consideration. I hope this will continue in the future (the more interdisciplinary engagement, the better!) and that categorical linguistics as a field will keep growing, ideally with more linguist colleagues joining in. And I certainly will keep participating in future ACT conferences too, so stay tuned! 😃

==The End==

Leave a comment