In my previous post Carving civilization into stone…and the “Chinese Rosetta Stone” (Part 1) I wrote about my recent discovery of a roadside stone carved with four seal-script characters 上譱[善]若水 shang4 shan4 ruo4 shui3 ‘the greatest virtue is like that of water’ (a famous quote from Tao Te Ching) and, from there, wrote a bit about the historical evolution of the Chinese writing system. In this post I’ll continue writing about historical Chinese scripts, focusing on an inscribed stone tablet that to some extent resembles the Egyptian Rosetta Stone. Read on and find out what I have in mind! 😃

The “Chinese Rosetta Stone”

So, while the differences between the various post-Qin Chinese scripts are rather trivial and mostly calligraphic, the differences between the chancery script and the prechancery scripts (e.g., the seal script, the oracle bone script) are a lot more substantial. As a result, people who are born in a post-chancery script era and haven’t been taught the seal script in school (i.e., most people today) have much difficulty in reading authentic pre-Qin texts—not only due to the grammatical changes from Old to Modern Chinese but also due to enormous visual changes in the writing system.

But then one may ask, How did people of (or closer to) our era figure out which pre-Qin character corresponded to which chancery-script character? Is there a Chinese counterpart of the Egyptian Rosetta Stone? (Thanks to Daniel Harbour for bringing up this interesting point to me!)

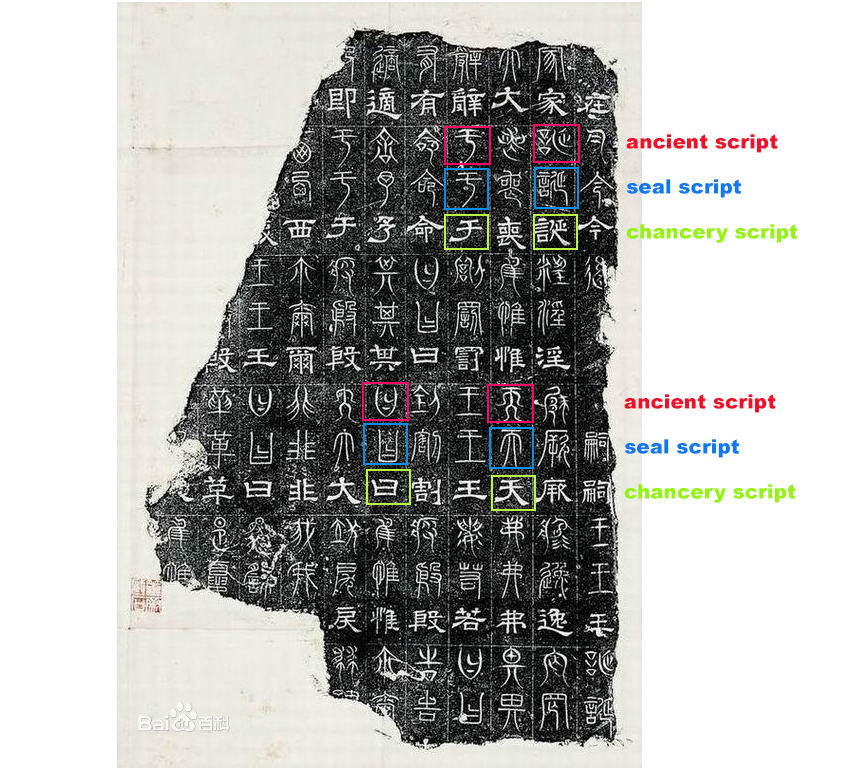

As it turns out, there does exist an inscribed stone tablet in Chinese history that to some extent resembles the Rosetta Stone. It is the “three-type stone classics” (三體石經 san1-ti3 shi2 jing1), aka the “Zhengshi stone classics” (正始石經 zheng4shi3 shi2 jing1). Being erected in 241 C.E. (i.e., the Three Kingdoms period) in the order of Zhengshi Emperor and rediscovered in 1895, the stone is inscribed with two Confucian classics (the Book of Documents and the Spring and Autumn Annals) in three scripts: the chancery script, the seal script, and the so-called ancient script (古文 gu3 wen2).

Strictly speaking, both names above refer to the text on the stone rather than the stone itself. I’ll just call the latter “the Three-Type Stone” (三體石 san1-ti3 shi2) by truncating the text name a bit. Incidentally, the san1-ti3 here is just the san1-ti3 in the name of the sci-fi novel I mentioned at the beginning of the previous post—both are written as 三體: 三 san1 simply means “three” but 體 ti3 means different things in the two names—a script type for the stone classics and a celestial body for the novel.

So far in this article we have already seen the chancery script and the seal script (go back to Part 1 if you want a second peek!), but what is the “ancient script”? Well, basically it’s a Chinese script used before Qin Dynasty (3rd century B.C.E.), more exactly before the first emperor of Qin (秦始皇 qin2 shi3 huang2) forced everyone to use the seal script. It’s interesting that this immediately pre-Qin script, which was definitely much younger than the oracle bone script and the bronzeware script, was already deemed “ancient” by dwellers of the third century. Maybe in another 500 years we’ll all be called ancient too! 😆

I’m not the only one who thinks the Three-Type Stone is reminiscent of the Rosetta Stone. A quick Google search reveals that at least two other sources have mentioned this analogy. The first source is a 2012 post by a Taiwanese blogger:

這石經特殊的地方有點像現藏於大英博物館的羅賽塔石。

“This special stone is a bit similar to the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum.”

And the second source is the Japanese Wikipedia page for the stone (Japanese versions of the Wikipedia pages on ancient Chinese scripts are surprisingly informative):

古文・篆書・隷書の3つの書体により共通のテキストが書かれていることから、俗に「中国版ロゼッタ・ストーン」といわれる。

Since the stone has the same text written on it in three scripts, the ancient script, the seal script, and the chancery script, it is informally called the “Chinese Rosetta Stone.”

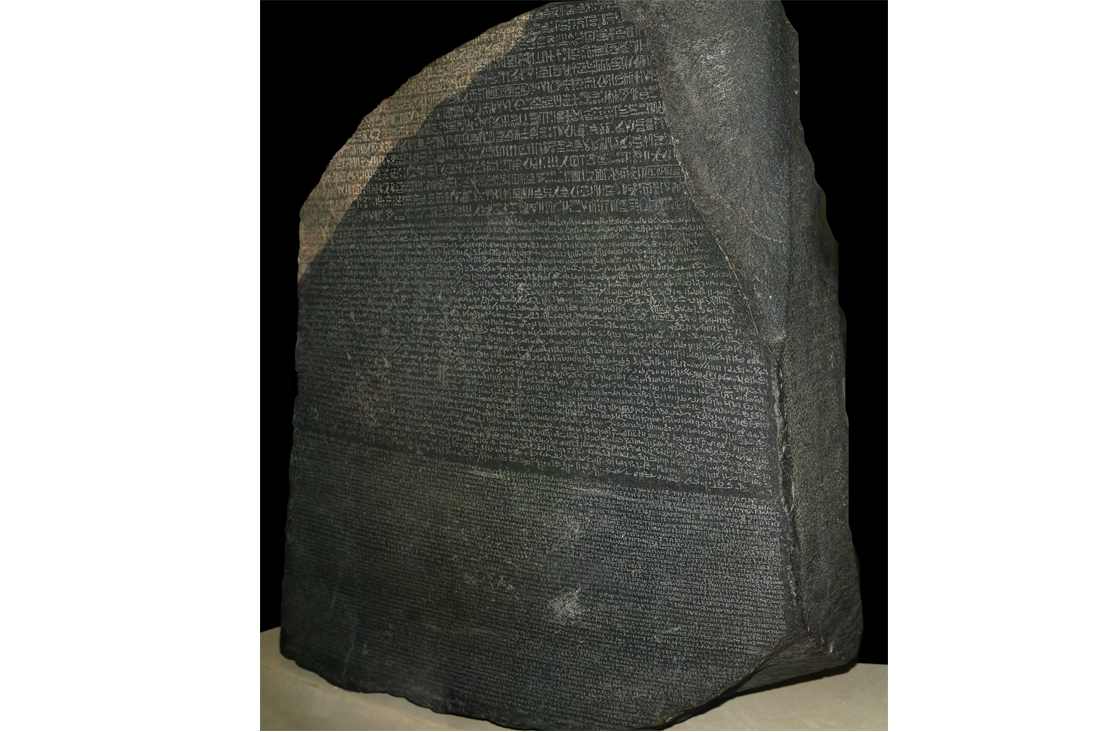

Despite what Wikipedia says, I haven’t found any Chinese sources calling the Three-Type Stone a “Chinese Rosetta Stone,” so maybe that informal appellation is only used in Japan. Anyway, since the analogy is two-directional, we can probably also call the Rosetta Stone an “Egyptian Three-Type Stone” (埃及三體石 ai1ji2 san1-ti3 shi2), for it also features three scripts (hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek) and hence lives up to that name. 😁

Rosetta Stone vs. Three-Type Stone

Despite their resemblance at first glance, I don’t actually think the Egyptian Rosetta Stone and the Chinese Three-Type Stone are that similar to each other. Nor can we say that they have commensurate scientific significance (well, basically the Rosetta Stone is much more significant). Below I’ll explain why, but before going into that I’d like to summarize their similarities a bit.

Similarities

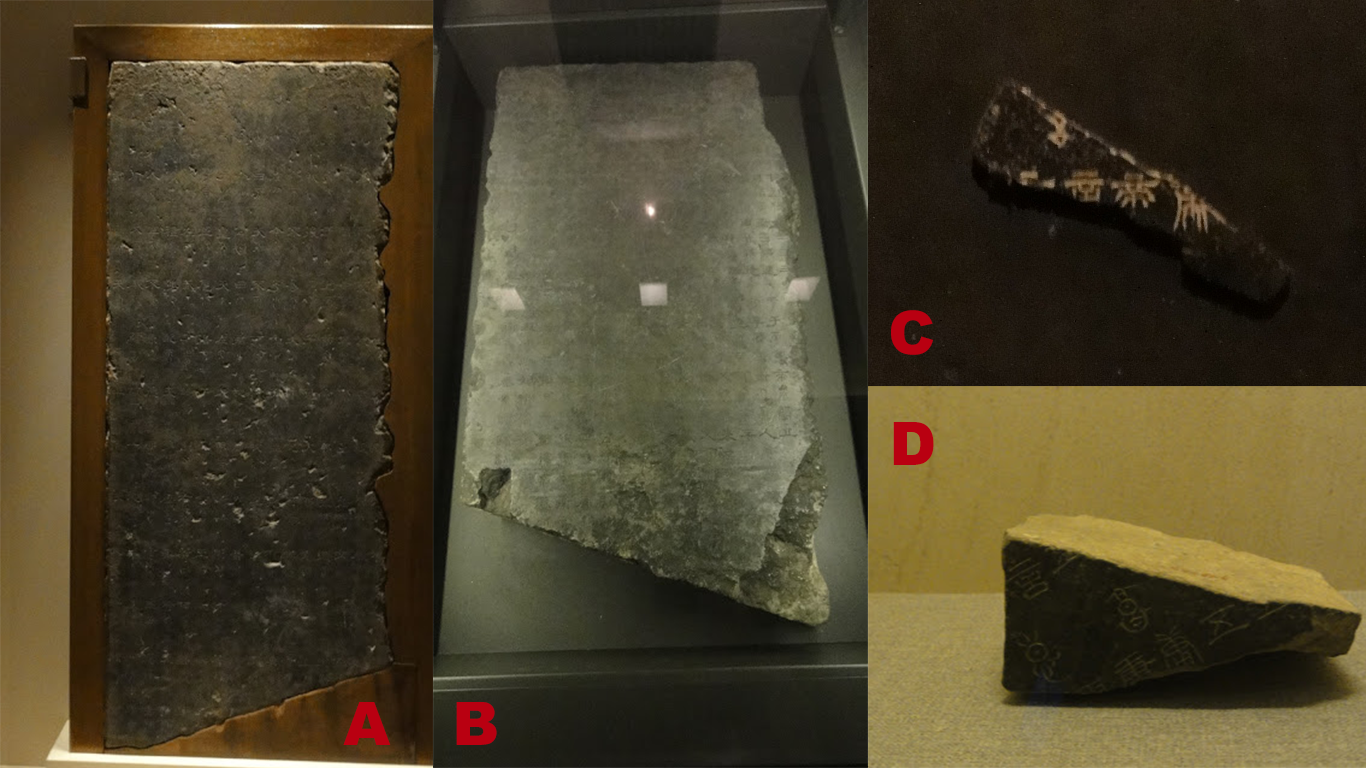

First off, they are both damaged and broken in several pieces. The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum is just “a fragment of a larger stele,” as is noted on its Wikipedia page, and according to Wikipedia this is also the only fragment that has been found.

Likewise, the Three-Type Stone unearthed in 1895 (in Luoyang, Henan Province) was also just a fragment. More luckily than the Rosetta Stone, several other fragments of the stone have been subsequently unearthed throughout the 20th century, though some of those fragments are really small!

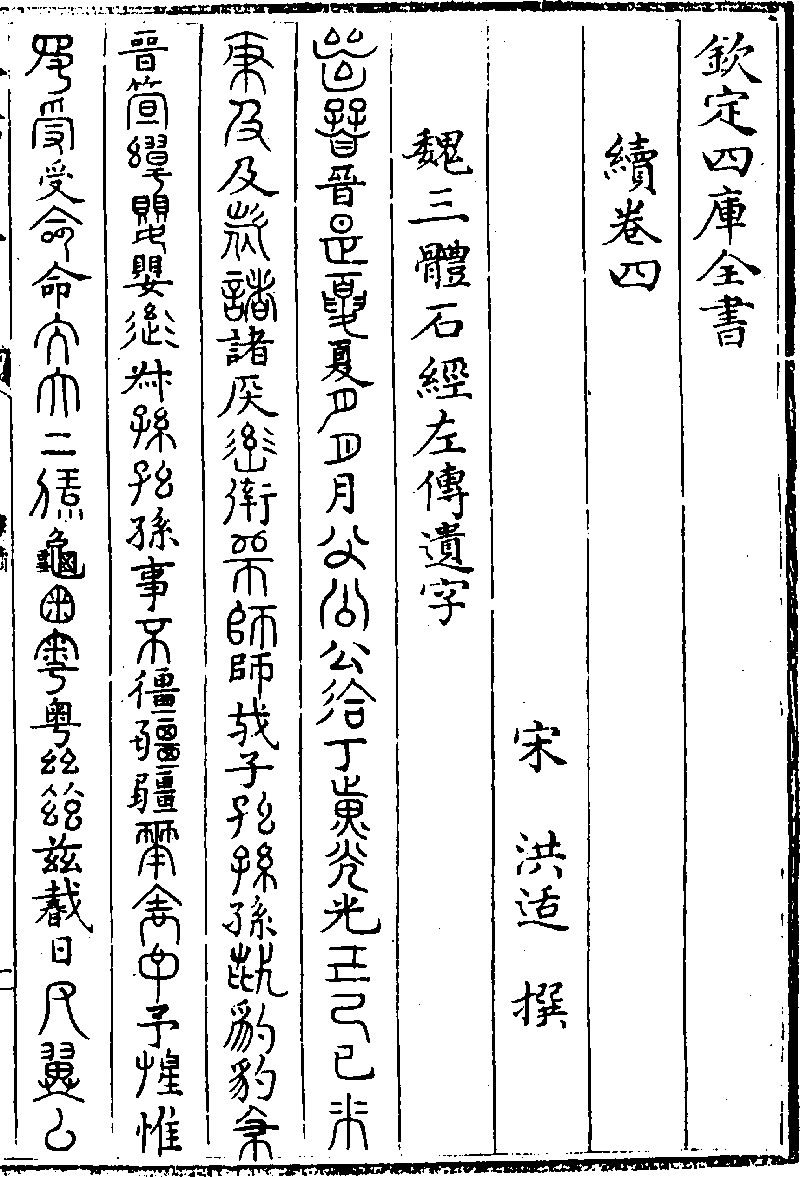

Note: While 1895 is the year when the Three-Type Stone was rediscovered, it is not the year when the stone was first seen (after its initial disappearance). A fragmentary documentation of its inscription was already included in a Song-Dynasty book by Hong Kuo in as early as 1053. The book, entitled Li4 Xu4 (隸續), is freely available on ctext.org.

Second, both the Rosetta Stone and the Three-Type Stone had been moved around to different locations in history and, sadly, reused as building material. The Rosetta Stone was reused to build Fort Julien near a Nile Delta town called Rosetta (or Rashid in Arabic), hence its name. And different fragments of the Three-Type Stone were reused first to build a Buddhist temple in Northern Wei Dynasty and later to build an everyday plinth in Sui Dynasty. In hindsight, the Rosetta Stone was perhaps a tad luckier, for the fort it had contributed to at least had a name!

Third and most obviously, both stones are carved with a single piece of text in three different scripts. I don’t have anything more to say about this similarity, as it is what had made me (as well as the Taiwanese blogger and the Japanese Wikipedia) think they are similar in the first place.

For the remaining content of this article see my next post Carving civilization into stone…and the “Chinese Rosetta Stone” (Part 3).

Leave a comment